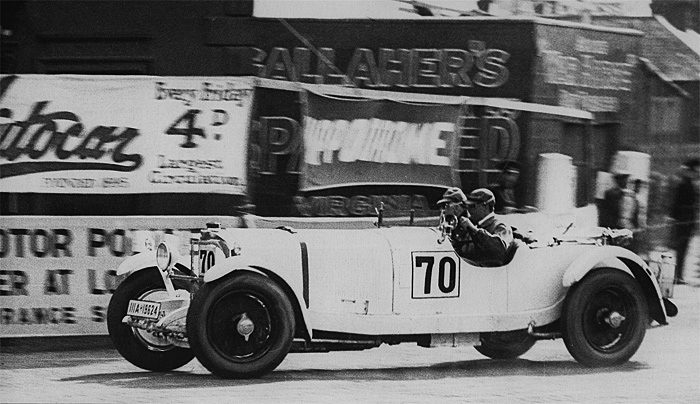

1929 Tourist Trophy – A Great Irish Triumph

By the Hon. H.R.S. Birkin

The chief threat to a Bentley victory was Caracciola’s 7-litre supercharged Mercedes. My 4 ½-litre Bentley, though supercharged too, stood little chance when we both started from scratch. The Alfas had a handicap of three laps, and the baby Austins of five. There were seventy-five entries.

In such a crowd the slightest mistake would be calamitous, not so much for the probability of an accident as for the opening it would give to the cars thronging behind. That this danger was realized became apparent when thousands of people streamed into Belfast, expecting a race which only skill could win, and unskill was certain to make sensational. The morning of the race came with gray skies and an ominous forecast of worse weather ahead.

On the first lap Caracciola led, and a fight began between the Mercedes and Glen Kidston’s 6 ½-litre Bentley. Almost at once the rain began to fall, and soon a storm was sweeping over the course, drenching the drivers and sending Catherine-wheels of spray from the tires. Bernard Rubin was the first to have a bad crash. He skidded, swerved wildly over the road, and in his own words, overturned slowly but gracefully. He tried to reach the switches to turn off the engine, but the engine had saved him the trouble. He and his mechanic lay underneath the car expecting another car to run into them at any moment. Their fear was luckily unfulfilled.

Rain brought no relenting to Caracciola’s amazing speed-he continued to pass the grandstand at over 110 mph. The water leaped off the hood and spurted in fountains around the wheels, but he seemed to have no trouble at all the corners. Glen stuck to him as bravely, and the crowds settled down under a rood of umbrellas to watch a wonderful race. But a Bradshaw’s Brae, going at 90 mph, Glen skidded, could not hold the car, missed a telegraph pole by a miracle and crashed nose first over a ditch.

Not even this could check the Mercedes, which lapped unfailingly at about 70, and then drew in to refuel. After twenty laps it gained on the three leading Austins with their handicap of five laps, while Campari was fourth in an Alfa that started with three laps. My Bentley was running beautifully, and W.O., who was acting as my mechanic, was delighted. He saw that we had no chance of catching the Mercedes with its three extra litres on level terms but he was alert throughout the race as any permanent mechanic could have been.

At twenty-five laps, with only five more to go, one Austin had fallen back, and the lead of the other two had been much reduced. Campari was still third, and the Mercedes was gaining furiously from fourth. The honor of England was under the hoods of the two Austins; as they scuttled past the stands they were greeted with amazed cheers. Whenever Caracciola passed them they were quite hidden from the spectators and seemed to be moving backward. Another rainstorm swept the road, but only at certain points, so that the surface was continually changing from dry to glassy. At Ballystockart Bridge, Clark, in an O.M., skidded., hit a hedge, and shot back into the middle of the road. Immediately a breakdown gang began to work to move it out of the way, and men ran with flags to signal danger to the cars behind. But they were to late. A Triumph could not stop in time, and the men, caught between this new danger and the wrecked O.M., had no hope of escape. Ambulance crews ran to their aid, but they could do nothing, and when I passed, there was little but the ruin of two carts and a frightened crowd to attest the tragedy.

Soon after this Caracciola passed Campari and roared in pursuit of the scurrying Austins. They were passed on the twenty-seventh lap after stopping to refuel. With three more laps to go, Campari was 54 seconds in front of Caracciola. On the twenty-ninth lap, at the beginning of the straight, Caracciola’s Mercedes flashed past Campari’s Alfa and settled the issue. Campari was second, and the baby Austins had a great welcome as they tripped in third and fourth.

Full Throttle (1932)