1973 Daytona Race Profile – Daytona Returns to 24 Hours

By Louis Galanos | Photos as credited

In the eyes of many who had attended the 24-Hours of Daytona since its inception in 1966 people and events in the early 1970’s were conspiring to make life difficult for this twice-around-the-clock enduro that is now so much a part of the history of endurance racing.

For one thing the ruling body for endurance racing, The Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA), had changed the racing rules again about engine sizes and this made producing prototype cars in the early 70’s more and more problematic for constructors. At the end of 1971 FIA rules changes outlawed the extremely popular and now iconic 5-liter cars like the Porsche 917 and Ferrari 512 and mandated only 3-liter engines for the 1972 championship season.

In 1972 the Group 6 Prototype and Group 5 Sports Car classes were both replaced by a new Group 5 Sports Car class. These cars were limited to 3-liter engines by the FIA (a move that some cynics believed was made to benefit the French Matra team), and manufacturers, like Porsche, gradually lost interest. Porsche decided not to participate in the newly renamed World Championship for Makes in 1972. Amid concerns that the 3-liter engines, normally used in shorter Formula One events, wouldn’t last for 24 hours the FIA and Ferrari applied pressure on Daytona’s Bill France to shorten his annual event to 6 hours, which he did. However, Sebring still ran its 12-hour race that year and Le Mans still did their 24-hour classic. End result was that the prestige of Daytona as a world-class endurance racing event suffered badly due to the changes and demands of the FIA.

For 1973 Bill France got permission to return to a 24-hour format but Ferrari decided not to show that year in what some automotive writers said was a manufactured dispute with France over appearance monies. Ferrari was asking for a 1200 percent increase in appearance money from the normal $2,500 to $30,000 and the notoriously tight-fisted France balked at their demands. As a result Ferrari decided to stay home and not compete in the opening round of the Championship of Makes for 1973. Also staying home was Alfa-Romeo but this had nothing to do with appearance monies. It seems that their new 3-liter cars were not quite ready for the February race.

The result of all this turmoil and rules changes within the championship series was a lackluster field of cars on the grid at Daytona on Saturday, February 3, 1973. There were only six pure 3-liter prototypes in the 53 cars to start the race. In that small group of prototypes were two John Wyer Ford Cosworth DFV V8-powered Gulf Mirage M-6 prototypes.

Englishman John Wyer was well-known to Daytona 24 race fans because of his association with the Gulf Porsche 917’s that won the overall trophy at Daytona in 1970 and 1971. To many who attended those races it was a golden era that sadly came to an end at the close of the 1971 championship season.

Wyer and engineer/team manager John Horsman had hoped to race a V-12 Weslake powered Gulf Mirage at Daytona but they experienced gearbox failure on two Hewland DG300 units in a four-day practice session at Daytona in January. Also, the V-12 had a nasty habit of not restarting every time it came in for fuel during the practice session. The only way they could get it going was with a push start. As a result of these problems Wyer and Horsman were forced to abandon racing the V-12 at Daytona in February and instead had to rely on cars powered by the Ford Cosworth DFV V-8. Those engines had been developed six years earlier and were considered an “antique” by auto racing standards. However, it was a proven engine with over 50 Grand Prix wins to its credit. Along with those Cosworth powered Mirages the team brought along one Weslake V-12 racer to see if recent gearbox modifications had corrected the problems experienced in earlier testing. The V-12 was on the Daytona entry list strictly as a training car.

Unfortunately after only a few laps on the Daytona track early Thursday morning of race week the V-12 came into the pits with a gearbox so hot it was about to seize. Gulf team manager John Horsman threw in the towel on the V-12 and turned his attention to the two V-8’s that would start the race. Before those cars could be gridded for the race they had to correct the problem of sagging front body panels.

On the 31-degree high banks at Daytona the downward forces on the cars were greater than they expected and caused the lightweight Mirage body panels to sag, necessitating reinforcement with a steel tube across the front of the car. As Horsman would find out later the sagging was caused by a supplier’s failure to properly cure the fiberglass epoxy when the panels were constructed. Recognizing that the Mirages were far from sorted out the PR man for Gulf, Eoin Young, said to the automotive press, “We’ll run as slow as we possibly can and still try to win.”

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Two

The lone French prototype entry at Daytona was a V-12 Matra-Simca MS670. Although some thought the V-12 was the fastest on the course it qualified second behind the pole sitting Bell/Ganley Mirage. The Matra was to be driven by Francois Cevert, Jean-Pierre Beltoise and Henri Pescarolo. The Mirage prototype of Mike Hailwood and John Watson qualified third and was followed in qualifying by a Ford Cosworth powered Lola T282 driven by Reine Wisell, Jean-Louis Lafosse and Hughes de Fierlant. The Lola, making its racing début, was entered by Scuderia Filipinetti and arrived in the USA virtually untested. The drivers were told to take it easy during the two days of practice and qualifying because they didn’t have a spare engine if anything went wrong.

Rounding up the 3-liter prototype entries were two veteran Porsche 908s. One was a Lufthansa-sponsored 908/03 entered and driven by Reinhold Joest who would co-drive with Mario Casoni and Paul Blancpain. Their team motto should have been, “If we didn’t have bad luck, we would have no luck at all.” The car was delayed at the Port of Jacksonville, stuck in a ship’s cargo hold until late on Thursday. As a result they missed the first day of practice and qualifying. During the second day (Friday) the car caught fire but the damage was repairable. The result of the fire was that they were unable to qualify when the session ended on Friday. Last but not least of the traditional prototypes was a Porsche 908/02 entered and driven by Canadian Harry Bytzek with co-drivers Rudy Bartling and Bert Kuehne. They qualified fifth on the grid.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Three

Porsche was ostensibly out of the business of building prototypes for the championship but due to circumstances had two of their brand new, supposedly private entry, Porsche 911 Carrera RS’s (the RS designation would later be changed to RSR) classified as prototypes instead of being in the Group 4 GT class where they technically belonged.

For Porsche the long, involved process of getting the new 911 Carreras approved by the FIA for the GT class was taking longer than usual. Porsche supposedly had met all the requirements for homologation but approval by the “Grand Poobahs” at the FIA had not yet arrived.

In a phone interview for this story Hurley Haywood indicated that he didn’t think there was any political motive for the Paris-based FIA’s slow approval of the Carrera RS for the GT class. It was just business as usual for the FIA.

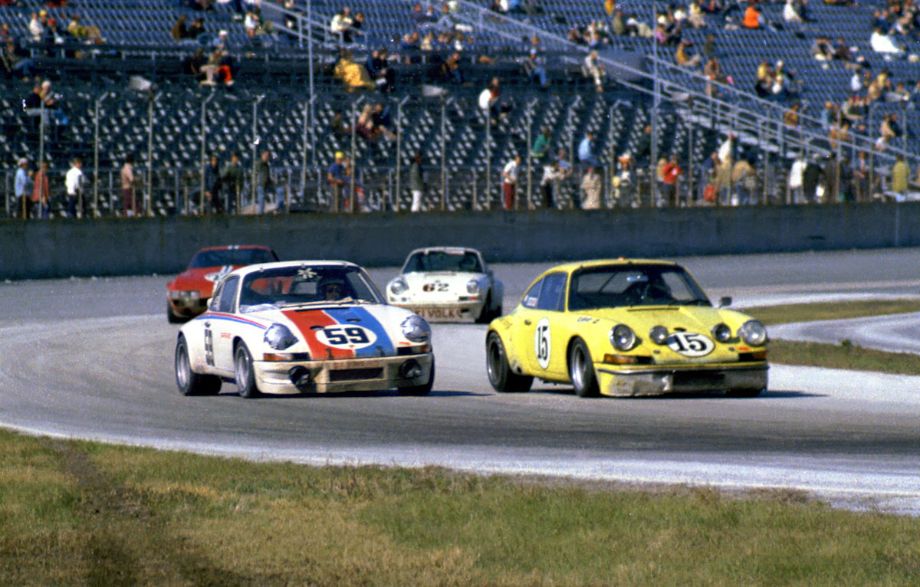

One of the two new 911 Carreras RS’s was given by the Porsche factory to Brumos Porsche of Jacksonville, Florida and would be driven by Peter Gregg and Hurley Haywood. Gregg, known to many as “Peter Perfect”, had abandoned the traditional tangerine orange Brumos paint job in favor of the now highly recognizable red, white and blue livery. Gregg adopted the new paint scheme for his cars because in the summer of 1972 he announced that Brumos Racing would become “America’s Porsche Racing Team.”

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Four

The other Porsche 911 Carrera RS at Daytona, in Sunoco blue, was entered by Penske Racing of Reading, Pennsylvania and would be driven by Mark Donohue and George Follmer. Roger Penske and his shop were known for immaculate car preparation and a Penske prepared Ferrari 512M set a Daytona course record in 1971 (133.919 mph) at the hands of Mark Donohue. In 1971 it was the dream of many Ferrari fans that Enzo Ferrari would allow Penske to prepare some of their 512M race cars. Only then, they thought, would Ferrari have a chance to beat the Porsche 917 in the championship that year. It was not to be.

At the time The Daytona Beach Morning Journal gave the impression in some of their stories that both of the new Porsche 911 Carrera RS’s were private entries, albeit with a little factory support. In reality both of the new Porsches were “factory owned” with the factory selecting respected American teams like Brumos and Penske to “represent Porsche” in the championship season opener at Daytona. This was a cooperative agreement between Porsche, Brumos and Penske and would be supervised by Porsche’s senior engineer, Norbert Singer.

Singer brought with him from Germany several factory mechanics who would help staff both the Brumos and Penske pits. During the race Singer did double duty by going back and forth between the two pits to talk to drivers, mechanics, asking questions and giving advice. Gregg later said that Singer told him if he kept the car under 7500 rpm it would last the 24 hours. That turned out to be good advice.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Five

“The Sunshine State” failed to live up to its name and weather for the first day of practice and qualifying on Thursday produced heavy rains. The handful of spectators taking shelter in the covered grandstands could see cars on the track throwing up rooster tails of spray. The rains kept speeds down as drivers negotiated the very slick track that was covered in standing water in some areas of the infield. The top qualifier that day was Henri Pescarolo in his V-12 Matra with a speed of 124.034 mph. For many of the other cars that day it was a washout with most not averaging 100 mph and the slowest came in at 72 mph. Recording a second-best time on that rainy day was Englishman Mike Hailwood driving one of the two John Wyer Gulf Mirages. His co-driver would be John Watson.

Among the first-day qualifiers was Richie Panch driving a Chevrolet Camaro Z28. Richie was the son of stock car legend Marvin Panch who had retired from racing and was working on his son’s pit crew. While international racing rules back then stipulated that a driver had to be 21-years-old Richie took the wheel of the Camaro at age 17. In fact he was a senior at Daytona’s Mainland High School and would graduate in June of that year. One more thing, his official entry form listed his age at 21. Seems the folks at the Speedway got a case of amnesia when dealing with a son of one of their NASCAR legends.

More rain was predicted for the second and last day (Friday) of practice and qualifying. The Gulf Mirage folks were able to get Derek Bell’s car out before the rains came and he captured the pole at 129.335 mph. The better weather and higher speeds on a damp track produced a couple of incidents. Bob Grossman driving the #21 NART Ferrari 365 GTB/4 kissed the wall going down the main straight losing the car’s hood. Damage was minimal and the car started in 17th position.

The other incident involved the Reinhold Joest Porsche 908/03 which caught fire in the infield. It was quite a dramatic moment captured by newspaper photos which showed Joest running from the car as flames leapt from the cockpit and front of the car. The following day the local Daytona newspaper reported that the car had been withdrawn but there it was on race day at the back of the grid in 47th position. Seems that the damage was relegated to the cockpit of the car and the quick action of the corner workers saved the day. However, it must have been a long night for the Joest mechanics as they removed and replaced burned-out wiring.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Six

Later that Friday morning the predicted rains came, throwing a monkey wrench into any attempt by the remaining cars to qualify for the race on Saturday. When the times of those rain-soaked cars were tabulated many did not make the minimum average speed (98.322 mph) to be placed on the grid.

Speedway President Bill France, Sr. was not pleased when he was informed that the starting grid would be far smaller than he expected. He arranged for a meeting with both the FIA and SCCA officials to see what could be worked out. Late Friday evening the officials announced that a third qualifying session would be held the day of the race (Saturday) between 10 am and 12 noon for those cars that didn’t make the cut. Seems that Mr. France was greatly worried about the appearance of a diminished starting field and wanted as many cars as possible out there to take the green flag for the reborn Daytona 24.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Seven

It had been reported later in a number of publications that, prior to the start of the ’73 race, Peter Gregg informed Roger Penske that he should ask his mechanics to check the flywheel bolts on the 911 Carrera RS Penske got from the Porsche factory. Gregg’s mechanics had taken their Porsche apart and found the flywheel to be loose on the Brumos car. These same published reports indicated that, “Penske felt it was a pre-race ploy and ignored the advice.” As the race results would show that decision to ignore Gregg’s advice might have been ill-advised.

In recent years the Daytona 24 had been blessed with a huge entry of GT cars much to the delight of American racing fans who came to Daytona hoping to see some American iron take a trophy or two. Among the GT favorites in 1973 were the Corvettes of John Greenwood, Tony De Lorenzo, Dave Heinz and Jerry Thompson as well as almost a dozen Z28 Camaros.

The Corvettes and Camaros would be dueling with over a dozen Porsche 911’s as well as four well-prepared Ferrari Daytonas. The four Ferrari Daytona 365GTB/4’s were entered by Luigi Chinetti’s North American Racing Team (NART). Chinetti’s son Luigi, Jr. would be diving one of the cars along with Bob Grossman. Other NART drivers included Jean-Claude Andruet, Claude Ballot-Léna, Arturo Merzario, Jean-Pierre Jarier, François Migault and Milt Minter.

The competition at Daytona in 1973 wasn’t relegated to just cars and drivers. Tire companies B.F. Goodrich and Goodyear had several cars shod with street radial tires. An overall or class win with those tires could be an advertising bonanza for either company. What the tire companies were not saying in their pre-race press releases is that these so-called “street” tires had been shaved down to almost half their tread depth. The Greenwood Corvettes, Penske Porsche and a NART Ferrari were all running on these special tires.

The additional practice/qualifying session on Saturday morning saw the now repaired Joest 908/03 on the track and all three drivers qualified. However the car would have to accept placement in the back of the pack. Also on the track were the two Gulf Mirages for final adjustments but noticeably absent was the Matra and the Lola T282. The absence of the Lola surprised many when it was learned how few laps they had actually taken in practice.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Eight

The weather on race day dawned bright and clear. The weather front had passed through the day before but along with the clear sunny skies came high winds and much cooler temperatures. No doubt some drivers welcomed the cooler temperatures when driving a race car but the high winds made driving at speed on the high banks a little tricky.

It was the Daytona 24 custom in those days to drop the green start flag, which they did at 3:03 pm, on the back stretch of the tri-oval. The accepted reason for this was safety. The faster cars could outpace the slower cars and prevent a traffic jam coming off the high banks and into turn one. Passing under the NASCAR start/finish line on the front straight was Derek Bell’s Mirage in the lead followed by the Mirage of teammate Mike Hailwood and then Francois Cevert in the Matra. Upon exiting the infield the Bell Mirage began to falter on the back straight and was eventually passed by Hailwood then Cevert’s Matra then the Lola of Reine Wisell. The Bell/Ganley Mirage was suffering from a loose alternator but they were able to keep ahead of the rest of the pack for the moment.

While the Hailwood/Watson Mirage maintained the lead the Cevert/Beltoise/Pescarolo Matra kept pace with the leader but did not appear to consider challenging them. As most know a 24-hour endurance race is not a sprint and running a conservative race could result in a win. Not running a conservative race, at least in the early minutes, was Arturo Merzario in his NART Ferrari Daytona. He powered his Ferrari Daytona through the infield turns with a great deal of opposite lock much to the pleasure of fans and photographers alike.

As with every endurance race there will be retirements and several cars bit the dust within the first 30 minutes. First on the list was one of the two John Buffum entered Ford Escorts that withdrew without completing even one lap. Next to withdraw was the Chitwood Racing Z28 after six laps followed by the John Greenwood Corvette. The Greenwood Corvette suffered a bit of bad luck when they had to pit early for tire problems Those problems were related to the street radials they were using for the race. During the tire change a car jack slipped and when the car fell the jack punched a hole in their radiator. In disgust Greenwood withdrew the car after only seven laps. Finally the last Buffum Escort was parked behind the pit wall after only nine laps.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Nine

According to estimates at the time there were 29,500 fans in attendance with most of them in the infield. The sights, sounds and smells in the infield can be quite mesmerizing. The sight of young girls in shorts hawking programs, the smell of steak cooking and the sounds of loud music could be heard over the growls of race cars. Young and old traversed the infield on bicycles and motorcycles with a dog or two running loose while one person had a cat on a leash.

Added to that mix were Army recruiters trying to sign up some cannon fodder for Vietnam despite the fact that a cease-fire had been signed with North Vietnam a week earlier. Even the Boy Scouts were present. They had the concession on recyclables and came prepared to collect cans and bottles tossed on the ground by the assembled throng.

Also in the infield were members of Porsche and Corvette clubs that had set up corrals for their respective club members. Both corrals were fenced off with a guard at the front entrance. “One must keep out the riff-raff mustn’t one.”

The heavy rains Thursday and Friday turned the eastern end of the infield into a mud bog that was slow-churned by a series of trucks and cars with some getting really stuck in the mud. An enterprising teenager from Daytona’s Seabreeze High School was there to pull out stuck cars, for a price, with his Jeep CJ5. Seems that he made gas money every weekend doing same for tourists who got their cars stuck in the soft sands of Daytona Beach.

With only two laps completed the Canadian Porsche 908/02 was in the pits to change a faulty wheel. From then on it was one thing after another but they would eventually finish the race 148 laps behind the winning car.

At lap nineteen Mark Donohue’s Porsche Carrera made an early pit stop for a quick tire change. Donohue told his crew that one of the wheels was out of balance and as it turned out some of the other cars shod with street radials had to pit for the same reason. The tire manufacturers at the track were having problems doing a proper speed balance on the shaved-down street tires.

Also in the pits at the same time was the Chevron B21 Ford of Hugh Kleinpeter, Jim Gammon and Tom Shelton. Their transmission was giving them headaches but they would carry on until forced to retire after 241 laps.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Ten

Considering all the problems the Mirages were giving the team going back to the earlier testing session at Daytona the team mechanics hoped they were prepared to deal with any problems that might arise. Well, they didn’t have long to wait as Derek Bell’s car entered the Mirage pits with a loose alternator mounting bracket which was followed not long after by a broken metering unit coupling. Next came a faulty spark plug that was causing severe misfiring then the clutch needed to be readjusted. Finally, after four hours of racing, co-driver Howden Ganley brought the car in to have the clutch thrust bearing replaced. This repair alone cost the team just over an hour.

The other Gulf Mirage seemed to be doing much better for the moment and as the sun began to set over the Speedway the Hailwood/Watson Mirage was in the lead with the Beltoise/Cevert/Pescarolo Matra in second. The Joest/Casoni/Blancpain 908/03 was third and the Gregg/Haywood Carrera was fourth followed by the Donohue/Follmer Carrera in fifth. At one point the leading Mirage had been clocked at just under 185 mph coming off of NASCAR four and onto the grandstand straight.

As darkness settled on the Speedway campfires began to spring up in the infield as the fans tried to ward off the February chill which was 15 degrees cooler than the previous day. Experienced Daytona race fans hoped that the winds, which blew all day, would continue throughout the night or the bowl-shaped racing facility might fill up with smoke from the campfires.

If the typical Atlantic Ocean morning fog came ashore, like it did most winters, it could combine with the smoke hanging over the Speedway and create dangerous visibility problems for the drivers. On at least one previous occasion Daytona race officials contemplated red flagging the race due to dense smog conditions.

Just after 6 pm the race saw its first spectacular accident as the 911S Porsche of Dominican Republic driver Horacio Alvarez lost control on the high banks as he was coming into NASCAR four. The race car began to spin and was headed toward the entrance to pit road when he hit a retaining wall and began to flip. And flip he did, over and over until landing right side up on all four wheels. The roof of his car was flattened down to the roll cage. Minutes later Alvarez strolled into the infield hospital, “…smoking a cigarette, and not injured.” Also retiring from the race, but not as dramatically, was the very quick Tony De Lorenzo – Maurice “Mo” Carter Corvette. It was sitting, forlorn and abandoned, on the back straight with a broken clutch after completing only 101 laps. They were the 13th car to retire and there were still 20 hours left to race.

One hour later the leading Hailwood/Watson Mirage had to pit for a clutch rebuild which allowed the Matra to take the lead with the Joest Porsche 908/03 in third place. Both Cevert and his co-drivers were racing conservatively. In fact their lap times were not much faster than the Porsches belonging to Brumos and Penske.

The Joest Porsche could not take advantage of the lengthy Mirage pit stop because they had to make an unscheduled pit stop themselves. The culprit was one of the fuel cells on the Porsche that was dragging on the track. They would eventually retire after 244 laps with gearbox problems.

With the prototypes experiencing so many problems the battle between the Brumos Carrera and the Penske Carrera began to take center stage as the cars moved up into second and third spot. Porsche fans were beginning to experience a bit of giddiness at the thought of street car like the Carrera possibly challenging the prototypes for the overall win at Daytona.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Eleven

Just then the Gregg/Haywood car was black flagged for a broken headlight. The track was beginning to crumble at certain locations which was nothing new for the Daytona facility. Asphalt pebbles were being throw up, damaging driving lights, head lights and pitting windshields on numerous cars. In 1967 pebbles from a crumbling Daytona infield track caused an accident that led to the retirement of the pole winning Chaparral 2F of Phil Hill and Mike Spence.

After a quick repair the Brumos Porsche returned to the track but the Penske Porsche was now ahead of them by a couple of laps. However, the Brumos car had one thing the Penske car did not and that was racing tires. The Penske car was fitted with street radials and was several seconds slower per lap than the Brumos car. The Brumos car began to reel in the Penske car.

The Matra continued its leisurely pace (114 mph average) around the track maintaining its lead. The sound of a Matra V-12 engine is very distinctive and one does not have to see the car to know it is coming toward you. It is an experience few who were at the races in those days will ever forget.

Just after midnight, 12:30 am Sunday to be exact, the sound of the Matra V-12 inexplicably ceased on lap 267. Cevert was at the wheel when the car rolled to a stop. He exited the car and lifted the engine hood to find a connecting rod protruding from the side of the engine block. The engine of the Matra let go at 9500 rpm which must have been one of those, “Holy U-Know-What!” moments for Cevert.

Around this time the Bell/Ganley Mirage was finally withdrawn after blowing its second clutch. The hopes of the Mirage team now turned to the Hailwood/Watson car but they were far back after spending over two hours in the pits for more repairs. Also in the pits for the umpteenth time was the Gitanes sponsored Ford Lola T282. They had a broken alternator pulley and had no spare for repairs. This necessitated a stop every 30 minutes to replace a depleted battery so their lights would function and prevent the car from getting black flagged. Finally around 2:30 am the car began to suffer from a severe misfire and finally retired after completing 281 laps.

No one could have predicted that after only 12 hours of racing the favored prototypes would be out of the race or suffering a variety of ills and far back. The lead in the Daytona 24 now landed in the lap of the Donohue/Follmer Porsche Carrera 911 RS. The gap between this 911 and the Brumos 911 was only two laps. The Gregg/Haywood Porsche had the potential of overtaking the Penske car but lost some time due to a longer than expected brake pad change.

Now in third place and 18 laps behind the leaders was the Merzario/Jarier Ferrari Daytona with the Minter/Migault Daytona in fourth and the Dave Heinz/Bob McLure/Dana English Corvette in fifth place but on the same lap as the Minter/Migault Ferrari.

The NART Daytona of Andruet/ Ballot-Léna was out after suffering a very hard crash entering the west banking. Luck was with driver Ballot-Léna because the right-side passenger door took the full brunt of the crash literally bending the car at that point. According to Luigi Chinetti, Jr., when uninjured Ballot-Léna got back to the pits he admitted to Luigi Chinetti, Sr. that the accident was all his fault. He even offered to pay for the repairs.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Twelve

During the next five hours little changed as the Penske Porsche held on to first place with the Brumos car a close second. The much faster Watson/Hailwood Mirage was gaining ground and making up for lost time thanks to the stellar driving of John Watson.

Around 5 am Mark Donohue made a scheduled pit stop for tires, fuel and a new driver. On a previous stop a question arose about the way the engine was performing. Automotive pundits would later comment that this engine problem was attributable to the loose flywheel that Gregg warned Penske about that was promptly dismissed by Penske.

When George Follmer exited the pits to continue the race their lead over the Brumos Porsche was now one lap. Fifteen minutes later the Penske Porsche began to emit smoke but the car continued for two more laps before Follmer guided his ailing car off the high banks and onto the apron heading for pit road. When the car stopped at its pit a huge blinding cloud of smoke erupted from the engine causing fire officials to come running with extinguishers. After leading for almost five hours the Penske Porsche was out of the race due to a holed piston. The Gregg/Haywood Porsche 911 Carrera RS was now in the lead with a 35 lap advantage and nine hours to go.

When I asked him about the retirement of the Penske Carrera RS Hurley Haywood said, “While I was not there when the Penske mechanics tore down the engine after the race I feel that the engine problems they suffered from could be traced to the same loose flywheel we discovered and fixed on the Brumos car.”

With the retirement of the Penske Porsche hopes were rekindled in the Mirage pits. After a quick pit stop the Watson/Hailwood car was in 11th place and if the Gregg/Haywood Porsche began to experience any kind of mechanical problems then there was a strong chance that their faster car could catch up to and pass the current leader in the time remaining.

Unfortunately circumstances dictated otherwise as the right lower suspension pin on the Mirage broke after 366 laps while Watson was doing 180 mph on the high banks. The collapsed suspension caused the car to spin with the front body section exploding off the car as it spun down the track to the apron and then into the infield. When asked later what was going through his mind when all this was going on Watson said, “All my birthdays had come at once.”

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Thirteen

As the sun rose over the Speedway the race fans who slept through the very noisy and eventful night began to awaken and many were shocked to see on the huge Speedway scoreboard who was in the lead. The common refrain was, “Wha’Happened?!!”

To say that Porsche fans were excited would be an understatement. One fan was seen marching through the infield with a huge Porsche flag attached to a long wooden dowel. Those in the Porsche corral were a little more circumspect as they began preparing breakfast because they knew there was still a lot of time left in the race and anything could happen.

And happen it did in those very early hours of Sunday morning. At the wheel of the leading Porsche was Hurley Haywood and after exiting turn six in the infield he rocketed down the back straight passing Lake Lloyd on his left. Then it happened, a big bang and the cockpit filled up with shards of glass, feathers and blood. One of Lake Lloyd’s many seagulls had crossed paths with the Porsche at 150 mph. When the initial shock of the collision was over Haywood radioed his pit to tell them the bad news. The pit did not have a spare windshield and signaled to him to stay out until they could find one.

In those days the standard practice, if you didn’t have a spare part, was to go into the paddock and find a compatible donor car. This happened in 1967 when the Ford factory team ran out of transmissions (they had twelve) and got one from a GT40 parked in the paddock. In 1970 a call went out over the PA system at Daytona for anyone with a BMW 2002. They used the same distributors that the Matras used that year and Matra needed to “borrow” a couple. The announcer promised the distributors would be returned after the race. At Sebring one year a Corvette team literally stole a rear axle from a race fan’s Corvette parked in the paddock. However, they were kind enough to leave a note on the windshield of the donor car.

The first attempt by the Brumos mechanics to find a windshield failed when the owner of a 911 flat refused. Finally someone agreed to let them remove the windshield from a compatible car. No doubt some arrangement had been made for payment or similar compensation. With windshield in hand the mechanics went to their pit where the signal went out to Haywood to bring the car in to replace the windshield and maybe do a little detailing to get rid of feathers, blood and other avian body parts in the cockpit.

It took ten laps (approx. 20 minutes) to locate, remove the donor windshield and get it to the Brumos pits. It must have been a macabre scene in the Brumos car as Hurley Haywood tooled around the track lap after lap with a dead ten pound (according to Haywood) bird part way in and out of the windshield. The Brumos pit used both their radio and signal board to inform Haywood to bring in the car. According to Haywood the radios back then were “pretty awful.” When he finally pitted it took just over eight minutes to replace the damaged windshield.

Watching all this drama from the pits were the other drivers and each time Haywood passed the finish line with a severely damaged windshield they began to question why the stewards were not black flagging the car.

Mario and Guido Levetto drove the San Remo Restaurant Camaro at that race in ’73. Mario indicated that a rumor circulated among the other drivers that the stewards were giving local boys (Gregg & Haywood) time to find a replacement windshield, get tools set up for the repair and maintain their lead. In his own words Hurley Haywood seemed to confirm this assessment. According to him, “Back then that kind of stuff was sort of overlooked. It was not like the windshield was flapping or lost its integrity. The only person who could see it degrade was me. I was going to keep going until they (my pit) told me what to do.”

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Fourteen

The accident with the errant bird no doubt scared everyone in the Brumos pits. You are holding a comfortable lead on your way to a win and this happens. No one could have predicted that. It was a miracle that Haywood hadn’t been injured by the bird strike or lost control of the car. It was to Haywood’s credit that he kept everything under control.

The unexpected bird strike on the leading car was of great concern to Norbert Singer. It was his job to see that the brand new Porsche 911 Carrera RSs finished the race and already one of them had retired. To be this close to a win and fail was unacceptable so after the car returned to the track, with Peter Gregg at the wheel, he kept a close eye on the lap charts to see what kind of lead they had and how fast the car was going.

When Singer was informed by the folks keeping the lap charts that the car had what was thought to be a comfortable lead he put out the order to the signal pit to have Gregg “SLOW” down. The signal went out but after several laps it was apparent that Gregg had ignored the order. Again the signal went out and again it was ignored.

At this point Singer made no further demands but Brumos General Manager Bob Snodgrass stepped in and talked to the signal pits by phone. The signal pits were on the straight between turns two and three and you could only communicate with them via phones set up in the pits just for this event. Finally the Brumos signal pit put out a board which read, “SINGER SAYS SLOW.” Only then did Gregg lift up on the accelerator. One must not bite the hand that feeds you.

The final hours of the race were without any further dramatics, bird strikes, accidents, blown engines and the like. There was a bit of drama in the Brumos pits when representatives of Classic Car Wax approached them with an offer they thought Brumos couldn’t refuse. If the leading Brumos Porsche would pit late in the race they would wash and wax the car in return for the princely sum of $10,000 (over $52,000 by today’s standards) along with the right to advertise same.

For several reasons Peter Gregg politely refused the offer and figuring prominently in his reasons was the fear that during the extended time in the pits, for the wash-n-wax, the car might not restart. That would spell disaster in epic proportions. To lose a race like the Daytona 24 because of a wash-n-wax would go down in automotive history and make Brumos and Peter Gregg a joke for years if not decades to come. The offer had to be declined.

When the checkered flag was waved, this time on the front straight, at 3:03 pm on Sunday the #59 red, white and blue Brumos Porsche crossed the finish line with a 22 lap lead over the Minter/Migault Daytona and 26 laps ahead of the Heinz/McClure/English Corvette. In fourth was the Porsche 911S of Bruce Jennings, George Stone and Mike Downs. Following them across the finish line was the NART Ferrari 365GTB/4 of Chinetti/Grossman/Shaw.

1973 24 Hours of Daytona – Race Profile and Photo Gallery Page Fifteen

The winning car covered 670 laps and 2,552.7 miles (4,108.16 km) at an average speed of 106.274 mph which was one of the slowest averages in recent times. The slowest on record for the Daytona 24 was back in 1969 when the winning Penske Lola T70 Mk. IIIB averaged only 99.268 mph at the hands of Mark Donohue and Chuck Parsons.

The first place money totaled $11,000 and in the winner’s circle Gregg commented to reporters that his car was probably the cheapest car ever to win the Daytona 24. According to Gregg the 911 Carrera RS cost only $25,000 while the winning Ferrari 312PB in 1972 probably cost $200,000. Gregg indicated he had no illusions about winning from the very start and was as much surprised as anyone that he won with what was a very new untested car. Gregg said, “Porsche thought this would be a good test for their new car…and I didn’t think it would finish.”

Over in the Mirage and Matra pits the disappointed mechanics and drivers were getting everything packed up for the trip back to Europe. Disappointment was very evident on the face of Matra team manager Gérard Ducarouge. He had confidently predicted an overall win before the start of the race but after his car retired while in the lead he commented, “…I think now it may be a hard season to win for France.”

In the paddock and infield camping areas fans were also preparing to leave. It was amazing how much useable stuff was left behind by the record crowd many of whom had spent four days camped out in the infield. You could furnish a small house with the chairs, tables, couches and other items left sitting on the frost-damaged infield grass.

Before they left several groups of race fans were asked about their reaction to the surprise win by the Brumos Porsche. As expected the Porsche fans were elated but many veteran Daytona attendees expressed disappointment that the race was won by what looked like a street car that you could purchase in any Porsche showroom. This was not what they came to see and reminisced about the days when Ford GT40s, Ferrari 512s and Porsche 917s blasted around the Daytona track.

The Gregg – Haywood victory was the first major international victory for a 911-based Porsche but it would not be the last. Gregg and Haywood would go on to win Sebring six weeks later in a 911, and 911-based cars would dominate sports car racing for a decade.

The Daytona 24-Hour race would continue to evolve for the next four decades going through a host of trials and tribulations including the energy crisis that caused the cancellation of 24 Hours of Daytona and Sebring 12-Hour GP in 1974. Over time the 24 Hours of Daytona has become and will remain an important fixture on the international racing calendar.

For Additional Reading

Corvette: Racing Legends, by Dr. Peter Gimenez, Ventura Publishing, Inc., 2008

Daytona 24 Hours: The Definitive History of America’s Great Endurance Race by J.J. O’Malley, David Bull Publishing, 2009

The Daytona Beach Morning Journal, Daytona Beach, Florida, Feb. 2-3-4, 1973

“Porsche Spring A Surprise” by Jeff Hutchinson, Autosport, February 8, 1973

Racing In The Rain by John Horsman, David Bull Publishing, 2006

WSC Giants Gulf-Mirage 1967 to 1982 by Ed McDonough, Veloce Books, February 2012

[Source: Lou Galanos]

What a treat to read this wonderful in-depth reporting on the 24 Hours. I’m a huge Brumos Porsche fan and really enjoyed reading about their first major win. Thanks to all!

Simply amazing and quite entertaining story, Bravo !!!! Being from the Great City of Titusville Florida just an hour from Daytona this story brings back so many memories of my childhood and dreams of piloting one of the 24 hour cars. The closest I ever got was having a few slot cars painted up in matching colors of some of those iconic teams…..

Good story and super photographs Lou. Brings back good memories of the era.

I was surprised to see the older ’68-69 Camaros and Mustangs in the race in ’73. I guess the technology in the classes they were in was not advancing as fast as the other classes. This was a wonderful article with fantastic pictures. Thanks so much for sending it our way.

I just read your article and re-lived my 1973 Daytona 24 Hr race. You made me remember details I had forgotten along with facts that I never knew. And I now know for sure that the rumor that was circulating in the paddock regarding the Porsche windshield was a fact…..the Haywood interview was revealing on this point and others.

I was on the backstretch and not far behind when Watson spun on the banking. I didn’t have to brake , although I probably instinctively took my foot off the gas for a second. There was really little chance that the car would return up the steep banking. The potential danger was finding pieces of car on the banking or oil. Also, at the time I couldn’t be sure whether or not other cars were involved. There were a few cars between me and Watson’s Mirage and they seemed to get thru without problems,,,,,and so did I.

Thanks Lou. AS usual: facts, details,and fantastic photos !

If anyone is interested in a personal video of the race derived from an old home movie film:

1973 Daytona 24 Hour Race; Part 1:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJ8lkbiDYA4

1973 Daytona 24 Hour Race; Part 2:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y08o35n8Q_0

Another great article, Lou. We lost a lot of time in the pits having to raise the car and add transmission fluid on every pit stop. The sling had been installed in reverse and instead of forcing fluid back into the gears was pushing it out. The undercarriage and the rear of the car was coated hence the nickname after the race, The Olive oil Special.

Guido, will you try to contact me? I crewed for Lamar and am looking for a good picture of the red/white #61 Vette.

Thanks,

Locke McCormick

North Florida Corvette Association

mccormick.robert@comcast.net

Marvelous machines and story line! Wonderful photos to recapture our imagination. Darn those 911s were awesome. Thanks for the memories Lou. (Phil Ward – Moondoggie Graphics and honored to be a friend of Lou.)

Another “Lou’s” moment – great story superbly told and illustrated with reams of outstanding pictures. The seagull incident could probably give a brand new meaning to the “bird’s eye view” expression. Thank you again for another great piece Lou!

Lou – you are a treasure trove of awesome stories and photos. Kudos.

Chris C aka cjcam

Incredible story and photos. Hurley can still drive with the best, even though now retired and doing the “rubber chicken” circuit which we all appreciate and are willing hands to do hot laps with him when the opportunity arises.

Great story and photos..! I remember leaving after the race, thinking about the low prototype turnout and the victory by a production car and figuring that it couldn’t get any worse than that- and then the next year they didn’t have the race at all!

Well-written as usual, Lou. If memory serves, I’d fallen asleep some time before midnight (in a small tent, in which I used to sleep quite well either in spite of or because of the sound). It seems that the absence of the scream of a certain V-12 engine either woke me or was the first thing I noticed upon waking up. Thanks for using a few of my photos. I hope to see you at the scene of the crime again in January. Maybe some of the posters here will be there and we can have a reunion of racing fans while we can still remember those days!

This is the first article of yours that I have read, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. My brother, Fred Lewis, forwarded it to me. It’s exciting to see the inclusion of some of his photos with yours and others who love this sport so much. He has mentioned you several times in our conversations….always with positive comments about your writing and love of racing. I’m not that knowledgeable on the subject….I only know how much Fred loves it and has as long as I can remember. Thanks for a great story and for being one of the good guys.

Another terrific documentary story, Lou. Thank you very much for sharing your recollections and photography. Even though I was half-a-planet away in the Navy in 1973, I still followed these races closely via Autoweek. I really liked seeing the photo of Bruce Jennings in the Joe Heishman 911S.

Enjoyed your article, and both photos and narrative combine to weave this detailed chapter of Daytona endurance racing. All your articles might be combined and published in book form, but regardless, thanks to Sports Car Digest, we have extensive archives that can be easily accessed. Your contributions are invaluable. Keep on keeping on, Lou.

Great story for a Brumo’s fan and a huge fan of endurance racing. The photographs are amazing too.

UNHEARD OF . . . . TOTAL 24hr. PIT TIME INCLUDING WINDSHIELD CHANGE . . . . 28 MINUTES ! ! If you don’t believe this PLEASE call Jack Atkinson . . . . Brumos crew chief EXTRAORDINARY at 321-543-0893

An excellent report on a race that was something of a bust; as always terrific photos.

Does anyone know why it appears that the two cars supplied to Penske & Brumos teams appear to have different style headlights? One would expect them to be the same, no?

I’m thinking that is Peter Gregg driving the #59 in the photo used at the beginning of the article. I have a Haywood autograph of that car that I took from late on Sunday. A good race but nothing like 1970 of course.