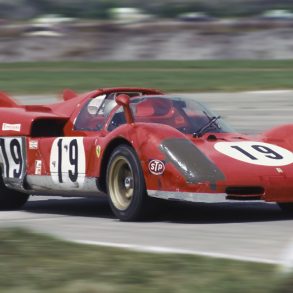

Photo: Pete Austin

He is, after all, Mario Andretti, one of the most accomplished racing drivers of all time, the only man to have won the Formula One World Championship, the Indianapolis 500, the Daytona 500, the 12 Hours of Sebring (three times) and the Pikes Peak Hillclimb. Throw in four American National Championships, an IROC crown and membership in three Halls of Fame, then remember that in addition to being the USA’s most prolific Grand Prix winner, and its most recent GP victor, he’s also the only American ever to win a United States Grand Prix. His 53 Indycar victories rank second only to A.J. Foyt, he’s the only man named U.S. Driver of the Year in three different decades, as well as being honored as Driver of the Century at the turn of the Millennium. This year marks the 45th anniversary of his 1969 Indy 500 win—six weeks or so before the Apollo XI mission—but the unfathomable aspect of that triumph is its singularity. He had several other excellent opportunities for victory both before and after that memorable Memorial Day, but the record shows only the one. Fortunately, the day before his 74th birthday he took some time to discuss those Indy experiences with VR Associate Editor John Zimmermann.

You came on the Indycar scene just as the transition from roadsters to rear-engined cars was happening, did you have any difficulty adapting to rear-engined cars?

Andretti: No, absolutely not. If you look at my transition—which I’m glad, by that way, that I have that under my belt—I had a taste of the roadsters and, you know, I came off a decent 2nd at Trenton, and my next experience out of the blue, with no testing or preparation, was at Indianapolis in the rear-engine car. It was to me as natural a transition as could be, mainly because, obviously, the advanced technology just made it an easier machine to drive. It was more stable, had more grip, all of it.[pullquote]

“I would not trade that part of my career for anything, because…I never drove the same thing, always something new, always something better.”

[/pullquote]

About that same time, tires got wider, engines got stronger, wings came in, was all that change and development exciting and satisfying to be a part of?

Andretti: Absolutely. I used to thrive on that. As you can imagine, I was involved in all of the race tire development at the time, which was very, very strong because of competition between Firestone and Goodyear. We were making some incredible progress, not only from year to year, but also almost during the season, from event to event, and I loved to be part of that. Then, of course, we started delving into aerodynamics. I was one of the first ones, the first one in Indycars, to put chin spoilers on my car, and when I did that—in Trenton, before Indy in ’67, I put that baby on pole and led every lap—I was basically copying the Chaparral. Then it started making sense, to get the downforce. There were limitations, and they would come up with a rule that you couldn’t have a suspended wing, it had to be attached to the body, and all that, but we were sort of getting around it. We were putting pieces on the exhaust and whatever, and we were getting into that part. It was all so much satisfaction from seeing how you would advance the cause. You just go faster and faster and then you’re beginning to understand all the dynamics.

I would not trade that part of my career for anything, because you were never ever bored, I never drove the same thing, always something new, always something better. From year to year throughout my career, right to the very end, every year I had a new car, and I was like a father waiting for a new baby, every year. Sometimes the baby was cross-eyed or something—not always a perfect baby—but it was new. There was always development, always work to do throughout the off-season, and that kept us really motivated, kept us really interested. Again, I’m very fortunate that I lived through that part of my career to really enjoy that. There was a certain freedom, and we were progressing, we were definitely progressing, which was the beautiful part about it.

When your car owner Al Dean died in 1967 you and Clint Brawner took over the team, but you only ran Andretti Racing Enterprises for one year, 1968, and then sold it to Andy Granatelli. Did you simply not want to be bothered with being a car owner?

Photo: Jim Hatfield

Andretti: That’s exactly right. I just didn’t want to. It was fashionable at the time because you notice that (Dan) Gurney and (A.J.) Foyt were becoming car owners because, basically, the tire companies, whichever side you were on, were financing most of it to protect their interests. On the Firestone side, they would give me pretty much what I would ask for, within reason, to match what the other drivers were doing. Then my ambitions were different; I wanted to move around, I wanted to have the best opportunity outside of my fold, and that’s why I decided to get out of that part of it. And then, quite honestly, to expand on that, I always had zero ambition to be a car owner. Zero ambition. Unlike my son Michael, all I cared about was driving—even to today.

How is Michael, who’s turned into a great car owner, different in that respect?

Andretti: Very different. Along the way he built his career with an eye on the business side of it, I was just totally different. He thrives on it. Michael always had, I think, a good business sense, he just truly enjoys that part, the entrepreneurial side of it, and that’s wonderful. He retired at the very top of his game when he was still of championship caliber, and then he went on and he never looked back. I tried to lure him into doing some long-distance racing with me after he retired, but it didn’t interest him. He’s happy with what he’s doing, and that’s wonderful.

After qualifying 4th and finishing 3rd as a rookie at the Speedway in ’65, you dropped out early the next three years, despite taking pole as fastest qualifier in ’66 and ’67. Did it seem like you were never going to win the 500?

Photo: IMS Photo

Andretti: Exactly right. I thought I had my arms around it pretty well, I had thousands of miles of testing already under me, the place was to my liking in every way, but for one reason or another things were not going my way. In ’68, especially, I did one lap and the wastegate on the turbocharger got stuck and I was (laughing) doing about 300 miles per hour on the back straightaway and burned a piston going into Three, and I figured, “Oh my gosh!” In ’69, things were going along in that Lotus four-wheel drive, which was a real barnburner as far as speed, but I think it was a godsend that the thing broke and almost killed me, because that at least put me in the Brawner car. That one was overheating so badly, I figured oh here it goes again, we’re up front…. But it lasted, it lasted all day! That was an unlikely race for me even to finish.

Was your first involvement with Andy Granatelli when you tested the Lotus Turbine in ’68?

Andretti: Yes. We always had some kind of a friendship, because we were both, you know, Italians, but he never really paid much attention to me when I really needed a ride, not until I was pretty much established. Then I wasn’t that much interested, because he was only shooting for Indy and I wanted the whole championship. Then, after his issues in ’67 and ’68 when he should have won but didn’t, I had a deal ongoing with Lotus for ’69 that was all put together in ’68. Andy liked that he could piggyback on that and then sponsor Colin (Chapman) on the other two cars, which were withdrawn after my crash. At least here we win with Andy. He was always going at it with the Novis and the turbines and all that, and now we won with a car that we had no plans of racing at Indy, and it was as standard as it could be (chuckles), and we finally won for him.

After winning, you raced a McNamara (see pages 8-9) for Andy the next two years, what can you say about that car?

Photo: IMS Photo

Andretti: It was interesting to be involved with something that was totally our own, but it seemed like Joe Karasek, the designer, was very new at the overall thing. You needed a road racer, but you needed a speedway car as well, and he did not quite get it totally, so we were always lacking something with that car. It was a better road racer. We tried pretty hard, for a couple of years, but it was really tough going, I think we only won one race with the McNamara.

After that you joined up with Parnelli Jones and Vel Miletich to form the so-called Super Team with Al Unser and Joe Leonard. Was it a promise of F1 that led you to do that?

Andretti: No promise of Formula One, no. At that point, I had already run Formula One for a couple of years, in ’68, I ran ’69, I ran ’70 and in ’71 I had already won my first Formula One race, and I had driven Lotus, I had driven March, and I had driven Ferrari by then. The lure of Formula One always existed somewhere in some corner. It was something that was in the back of my head to pursue, but the financial side here was so much stronger at the time that I could not overlook that because that was the security for my family, to make sure that if something happened to me they’d be taken care of. That was part of my reasoning at the time, and I could not overlook that, so that’s why I had to wait until the right time to get into Formula One. So we just brought in Maurice Philippe, we took him away from Lotus, to join us and design (Parnelli) Indycars, and then, of course, all of that led to the Formula One program.

When you joined Penske Racing, you were concentrating pretty much on F1. How do you remember your time with Roger?

Andretti: It was wonderful, as you can imagine, I always wanted to drive for Roger and it’s too bad I never had the chance to drive full-time. The reason I wound up with Roger was because in ’76, while on the grid at Long Beach, Chris Economaki stuffs a microphone in my face and says (here he imitates Economaki’s distinctive voice) “Mario, what do you think about Vel Miletich pulling out of Formula One after this race?” Well, he never told me anything, and I was so upset. The next day I made a deal with Colin without even talking to Vel, but then Vel and Parnelli said, “You gotta drive for us now, just in Indycars since we decided to pull out.” But I said, “No, I will never drive for you again. I will drive Indycars,” I said, “but I will not drive for you.” And they said, “We’ll sue you.” And I said, “Go ahead.” That’s when I called Roger and said, “I’d like to drive for you on a part-time basis whenever I can fit it in,” and he said, “Sure, sure. I’ll have a car for you.” So I made a deal with Roger.

A couple of years with Pat Patrick followed your time with Penske, and you, let’s say, nearly won the 500 again in ’81. Can you discuss losing that second win?

Andretti: Well, the part that I could never swallow, to this day, was the fact that the rule was ignored. I’ll explain: Roger obviously appealed (Bobby Unser’s post-race penalty), and then he dragged it on and he had his high-powered lawyers that made fools out of the ones at Indy and he got it the way he wanted. He got a panel of three judges to make the decision, which totally ignored the rulebook, and their rendering at the end was that the penalty was too severe for the occasion, so they gave him a $40,000 fine and reinstated him as the winner.

The following year at the drivers meeting I asked (IMS Chief Steward) Tom Binford—this was not Binford’s fault, because Binford was the one who upheld the rule in the first place and gave the penalty—“Tom, did the rules change from last year to this year?” He said, “Nope.” I said, “OK, so if I pass 11 cars under the yellow and get into the lead and then cross the finish line first, what will the fine be this year?” “No, no, the rule says you’re going to be docked a minute,” and so forth. “So, the rule applies this year but it didn’t apply last year…” You know what I mean? It was a farce. It was a joke. If you look at the video, at that time Jackie Stewart was doing the color commentating with Jim McKay, and he said, “Oh, he can’t do that, they came out of the pits together.” He first, me second, we came out of the pits together. And the blend line was at the end of the pits, and the whole field was just alongside of us. I looked to the side, and it was Foyt that I lined up with, and the rule was to blend in coming out of Turn 2, with the car that you came out alongside at the end of the pit wall. There was a question of whether to fall in, in front of or behind Foyt, but apparently Foyt was a lap behind at that time and he let me go in front. So, fine, he let me go in front. And Bobby went up 11 cars, right to the lead. You know, we’ll never know if I would have won it anyway, whether I would have been right behind him, but he clearly broke the rule. He just passed 11 cars under the yellow, no question about it. I mean that was the rule, and so (laughs) in those days they would review things. Today, probably because of computers and so forth, they have a lot better accessibility to things, they would probably have given him a stop-and-go, but in those days it was review everything. We didn’t even have to protest. We were going to protest, (crew chief) Jim McGee, said, “We’ve got this race, we’re going to protest,” but we didn’t even have to protest. I got a call from McGee at 5 in the morning, saying, “You won the race.” So I said, “OK, it is what it is, so OK.” Then it all turned out like it did. But I’m still wearin’ the ring, by the way! They gave me the keys to the pace car (laughing), but then they wouldn’t let me go to it! We did the banquet and everything; we went through the whole gamut!

Then the next year, in ’82, you were starting on the second row and had the incident at the start with Kevin Cogan. What happened there?

Andretti: It’s one of those things. You were upset, but you knew he didn’t want to do it either, take himself out. Just one of those things. It happened. Like you saw some years later, I think in ’92, I was in the front row with (Roberto) Guerrero, who was on pole, and I always say to the guys, you know, when you’re out there running, don’t buzz the freaking tires, because you’ve got stagger, and the tires are so hard, and they’re cold, you’re gonna spin it. That’s one thing I always watch, because it was so easy to spin the damn thing, and that’s what they did, and that’s what Cogan did, just buzzed the tires at the start, and just lost it, and so did Guerrero. He did it just trying to warm up the tires during the parade lap! Imagine that.

After that you opened your long-term relationship with Carl Haas and Paul Newman. Can you tell us about working with the two of them?

Andretti: The fact that I drove 12 seasons for them, you can see that I found a wonderful home. That’s the longest stint I had with any team throughout my career. I had there what I wanted, in many ways. I had input in the team, Carl and I got along really, really well and, of course, Paul, everything just meshed. We had one of the best teams ever, and it was a group that was so cohesive, and even now everybody has a good feeling for the days that they worked together. And, after I came out of Formula One I won 18 more Champ Car races, and that was in my 40s already, so you can see I enjoyed being with them to the fullest. Lola was really strong at the time and we kept improving, so we were always at the top of our game, I always felt competitive, we should have won a couple of Indys—I don’t think anybody dominated Indy like I did in ’87. I had Adrian Newey with me that year and there was nobody close to us.

You nearly won again in ’85 and then as you say, had the race all but won in ’87, can you discuss those two 500s?

Andretti: In ’85, I was just running too damn conservative, you know, trying to keep the revs down because the engine guys, Franz Weis, always used to just scream, “Keep the revs down!” I wanted to finish, because I had had so many failures, and I thought that I had the best of Danny (Sullivan), but obviously I didn’t. I should have just run harder as soon as he passed me, but then I figured, well screw it, and I just shifted into a lower gear and I was running all over him, but it was too late.

In ’87, here again, I had so much of a lead that I was running in top gear, which set up bad harmonics in the engine. In fact, they re-ran an engine on a dyno, based on the computer we had on board—already in those days—and we ran the same rev range I ran throughout the race and the thing broke about the same time as mine broke, dropped a valve. Then they ran another engine, 600 revs higher, which was my next gear, my aggressive gear, 600 revs harder, and I would have finished the race. I felt a vibration, but the engine guys would always say, “Keep the revs down, keep the revs down.” So I figured well, I’m just trying to bring it home. If, at that time, I would have had somebody on my tail trying to race me, it would have probably been a godsend, because I would have had to use up the revs and I would have been fine.

You seemed almost to have St. Christopher riding with you at all times, as you were able to walk away from most accidents. Was the one in ’92 at the Speedway your worst injury?

Andretti: It was one of them. I think Michigan in ’85 was probably worse. Still, I was lucky all along, look what happened to my son Jeff that same day (in ’92 he smashed both legs –Ed.). So, I had injuries, but in my entire career I only missed two races through injuries. I was lucky there, very lucky, and I know that. Believe me, I’m knocking wood right now. Look at 2003; that flip that I had and walked away…. So, the Speedway has been good to me. They had this joke about the Andretti Curse, but there is no Andretti Curse. We have a lot to be thankful for, regardless. Sure we would have liked to have won more, even Michael, look at how many times he dominated…and then just handed it over to the Unsers like I did.

There has been some speculation that you retired a year or two early. Do you share that view?

Andretti: Well, even my wife tells me that. Probably so. I had a fear of over-staying, because I had seen some other guys, and I wanted to have a memory of being competitive, because your last memory is always a very strong memory. I had some regrets for like the first six months or so, but I think I did the right thing, ultimately. How could I complain? I just count my blessings. I was able to retire on my own terms, and what’s better than that? I could have pushed the envelope a little more, but no one has driven much later than me, I don’t think. No one has won a race at age 53 yet. So I pushed the envelope pretty far.

Regardless of the fact that I only had one victory at Indy, I feel that I’ve gotten a lot more out of it. A lot of people realize that, mainly because of the fact that, I think, I’m third all-time in laps led, and things like that, so you can see I had a good time. Being competitive there, that’s what it’s all about. My satisfaction was there throughout my career, I love the place, I knew how to drive it, right to the last moment, and that’s all I could ask for.