More Cylinders: Jessie Vincent and the Packard Twin Six engine

“The greatest piece of machinery that ever went upon the highways,” proclaimed Henry B. Joy, Packard president in 1915, extoling the virtues of the recent release of his company’s new engineering marvel, the Twin Six. Jessie Vincent, the brainchild of the Packard Twin Six, came to the Packard Motor Car Company in July of 1912 after a highly successful tenure at the Burroughs Adding Machine Company making his mark building “a thick portfolio of patents.” He was interested in automobiles and made himself foreman of the company’s garage, where he made all the repairs and adjustments to the Burroughs fleet of executive cars in Detroit before moving on to become acting chief engineer for the Hudson Motor Car Company. He was not with Hudson long before Alvan Macauley, who earlier worked with Vincent at Burroughs, got him to join Packard, in July of 1912. (Packard president Henry B. Joy hired Macauley to be Packard General Manager in 1910). Macauley named Vincent Chief Engineer of the Packard Motor Company, a position he would maintain for the next 40 years.

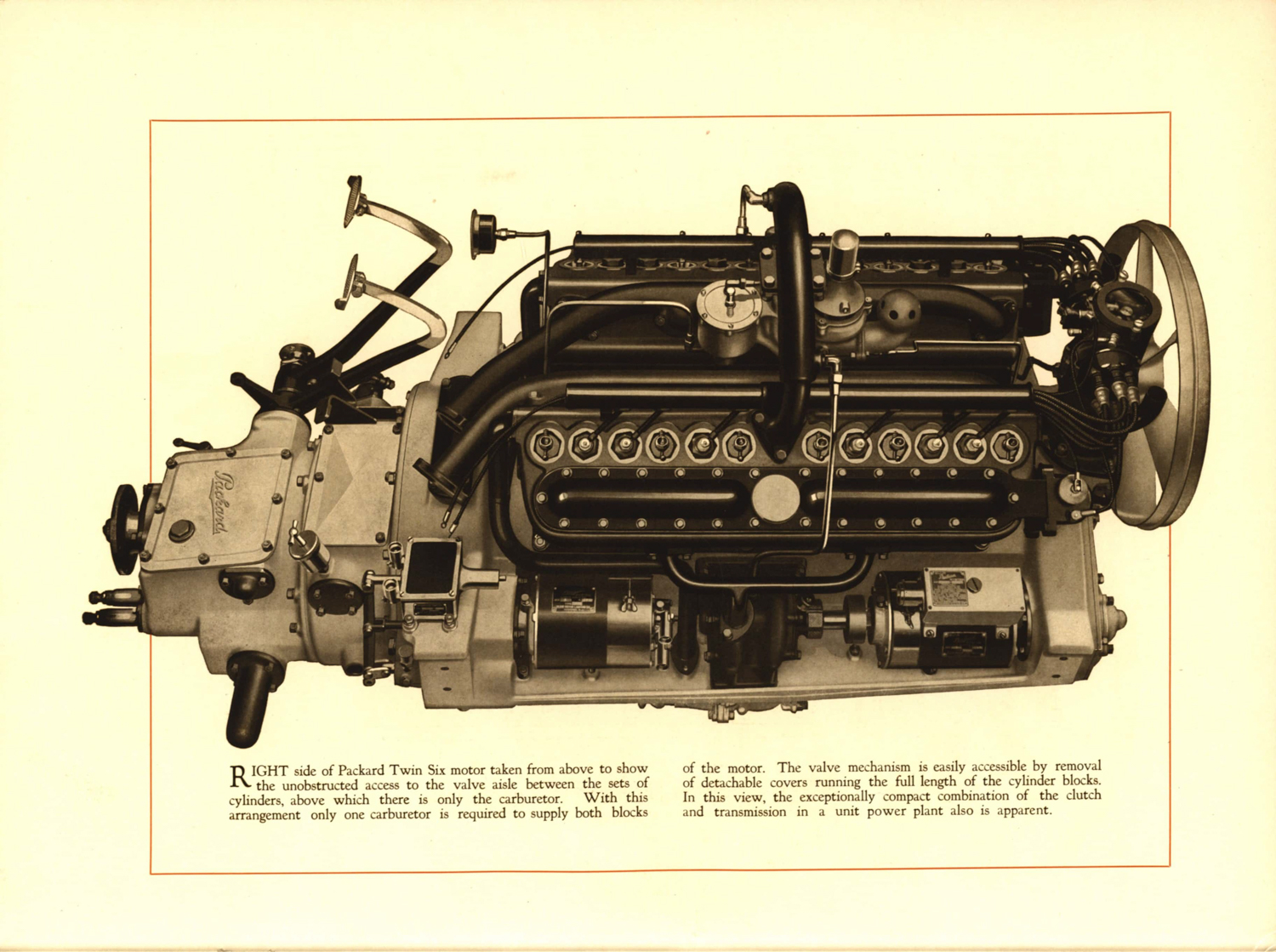

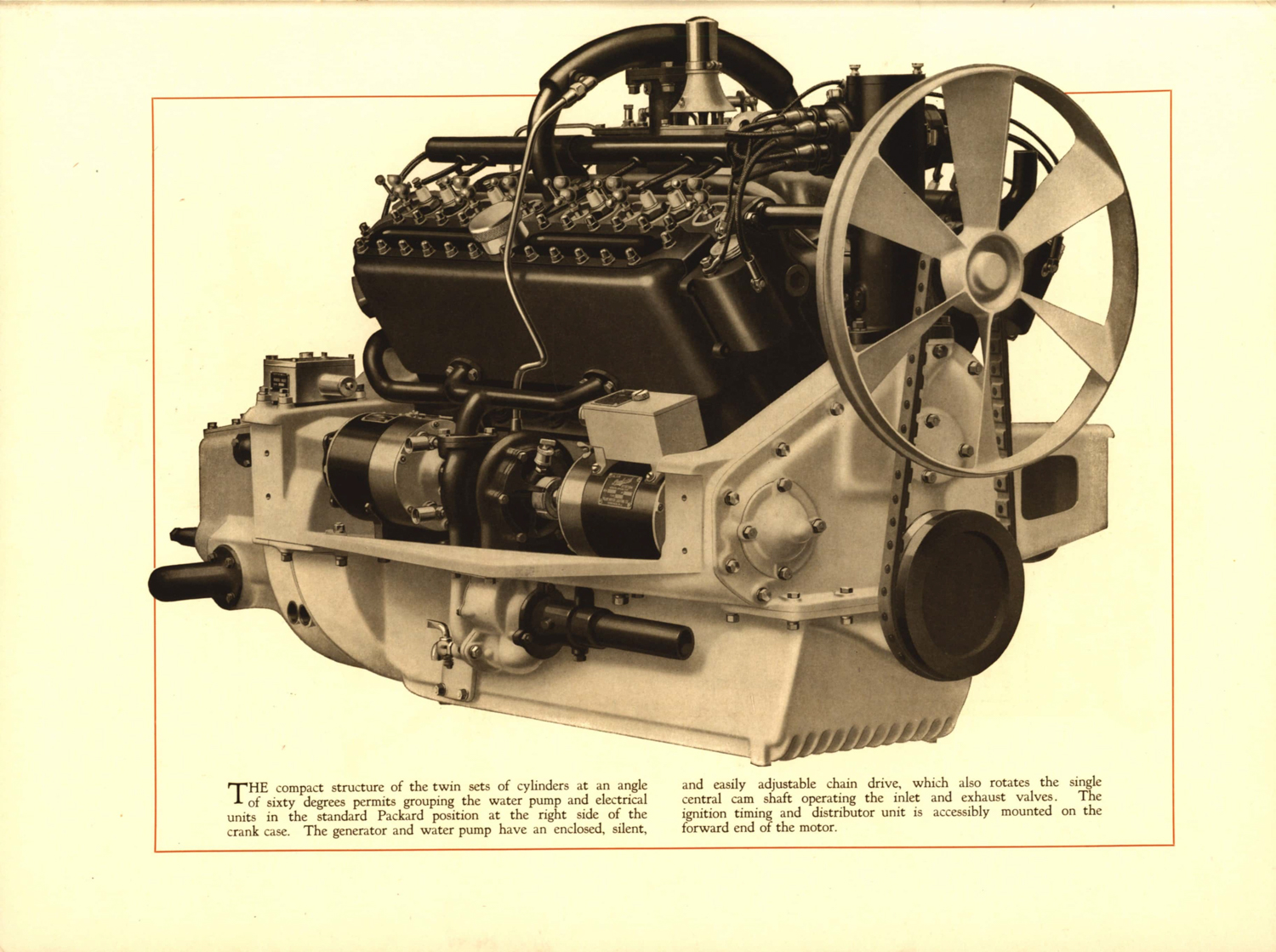

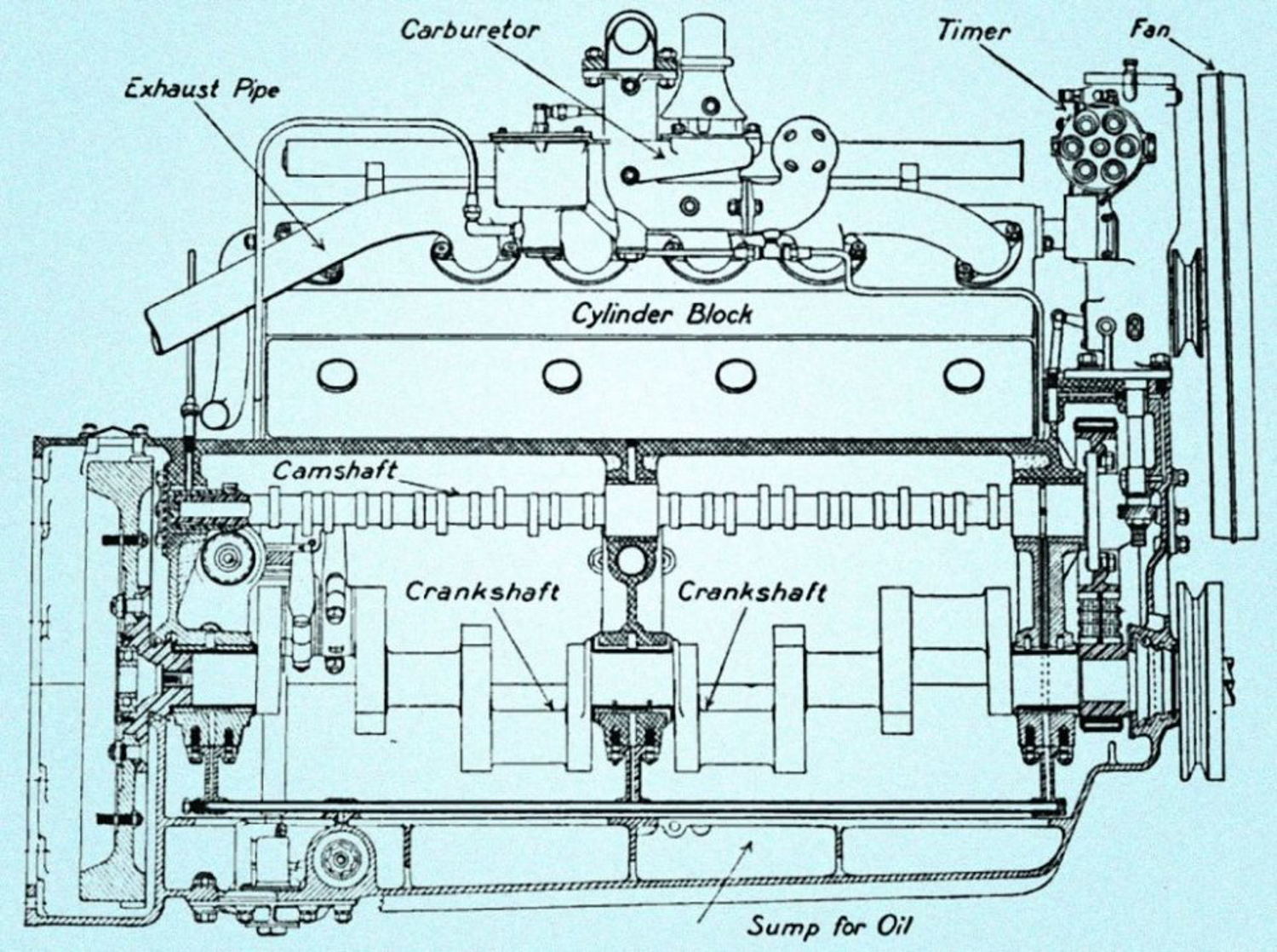

Vincent wanted to build a powerful, super-smooth and quiet running engine and was convinced a 12-cylinder design, not a V-8 configuration, was the best way to achieve his goal. Vincent agreed that the V-8 had it merits: more torque, less weight from having a shorter crankshaft and lighter pistons, as well as a little more smoothness at moderate speeds. However, he pointed out some disadvantages in the V-8, noting the V-8 would produce more vibration at higher speeds, make necessary mounting engine accessories such as the water pump, generator and starter motor either below the frame exposing them to moisture, or between the cylinder blocks, making the valves inaccessible. Additionally, the V-8 design would require a wider frame resulting in a wider turning radius and a steering gear that would be “very difficult” to assemble and to service.

Vincent’s solution was more cylinders. As Packard’s company magazine, The Packard, reported “one day the executive session was broken up by the engineering chief’s laconic: ‘I’ve got something to read.’ There were thirty-five pages of it. Joy, Macauley, Beall, Hills et al., listened first with respect, then with astonishment. Those pages contained a complete and convincing presentation of the Packard Twin Six motor.”

One of his presentations to Packard salesmen was later edited and condensed to produce a booklet entitled “How Many Cylinders”. Vincent’s design philosophy was made clear when he wrote, “From the time when the first practical car made its first run on the road, there have been three things which every motorist asked for- more range of ability, greater smoothness and less noise…. Today the demand is still the same, though we have come much closer to Absolute Quietness, Absolute Smoothness and the Maximum Range of Ability desired.

“The single cylinder gave way to the two, because the latter came nearer to satisfying the demand. So did the two go out to before the four, and the four, in turn, vanish at the perfection of the six, for the same reason. All the way, the tendency has been to make each impulse, each explosion in the motor, smaller in magnitude, but to get the power by many impulses in quick succession.

“A six-cylinder motor is theoretically in absolute perfect balance, but this is because the vibratory forces due to the rise and fall of one piston are neutralized by equal and opposite forces due to another. The pistons form what mathematicians call a ‘system of bodies’, and the forces existing in each individually have no effect on the whole lot considered together, because of the cancelling of one force against another force. Now it is only possible to cancel out forces in this way if they are tied together strongly.” Vincent firmly believed that the smoothness and quiet of the Six could only be made possible by weight— a substantially heavy crankcase and crankshaft plus a rigid flywheel to keep bearings from whipping and bending. He advocated for an engine with more pistons than the Six stating, “We want not only the present ability, but we want a greater range of ability. So the only way to go is more pistons.”

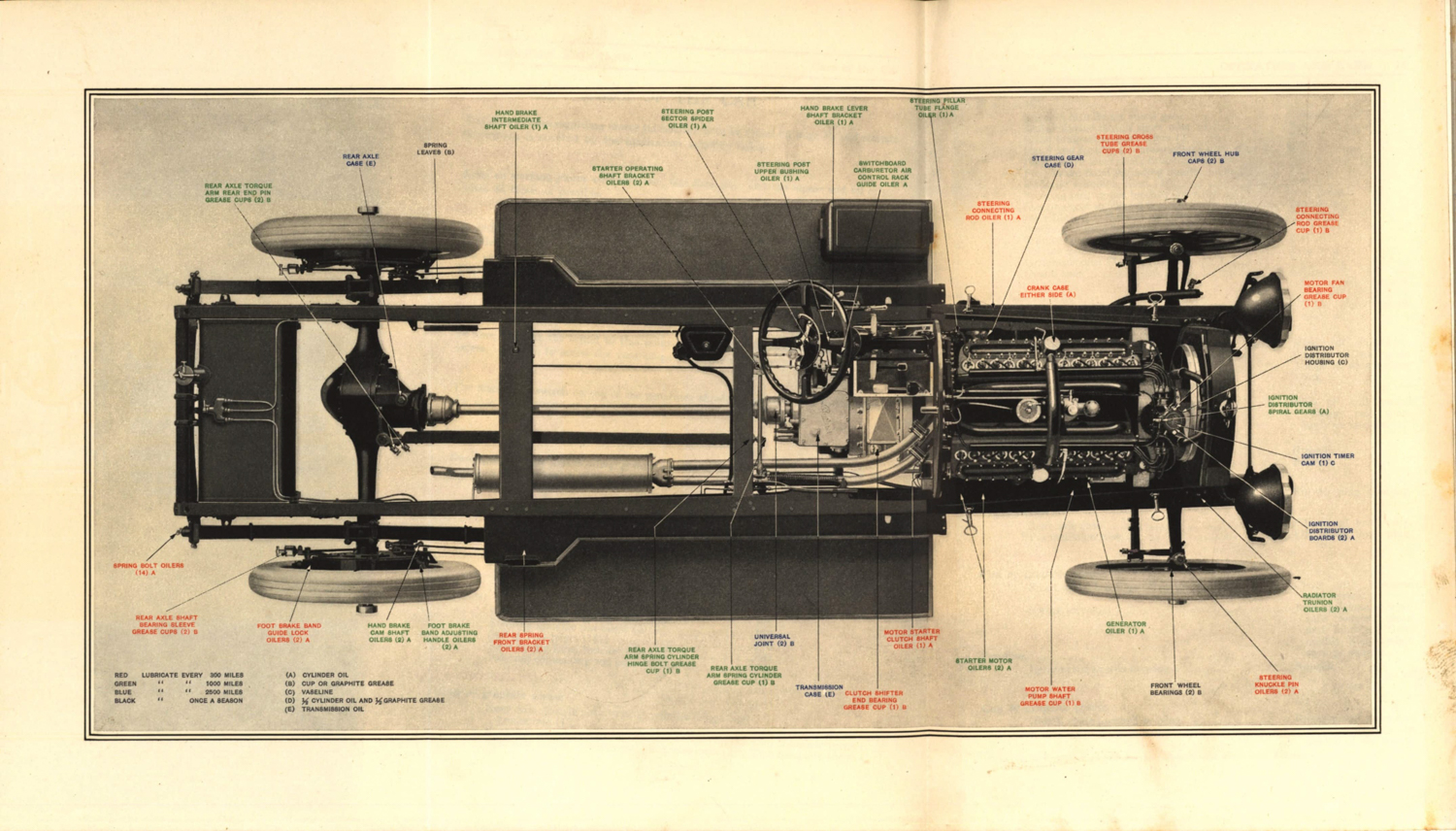

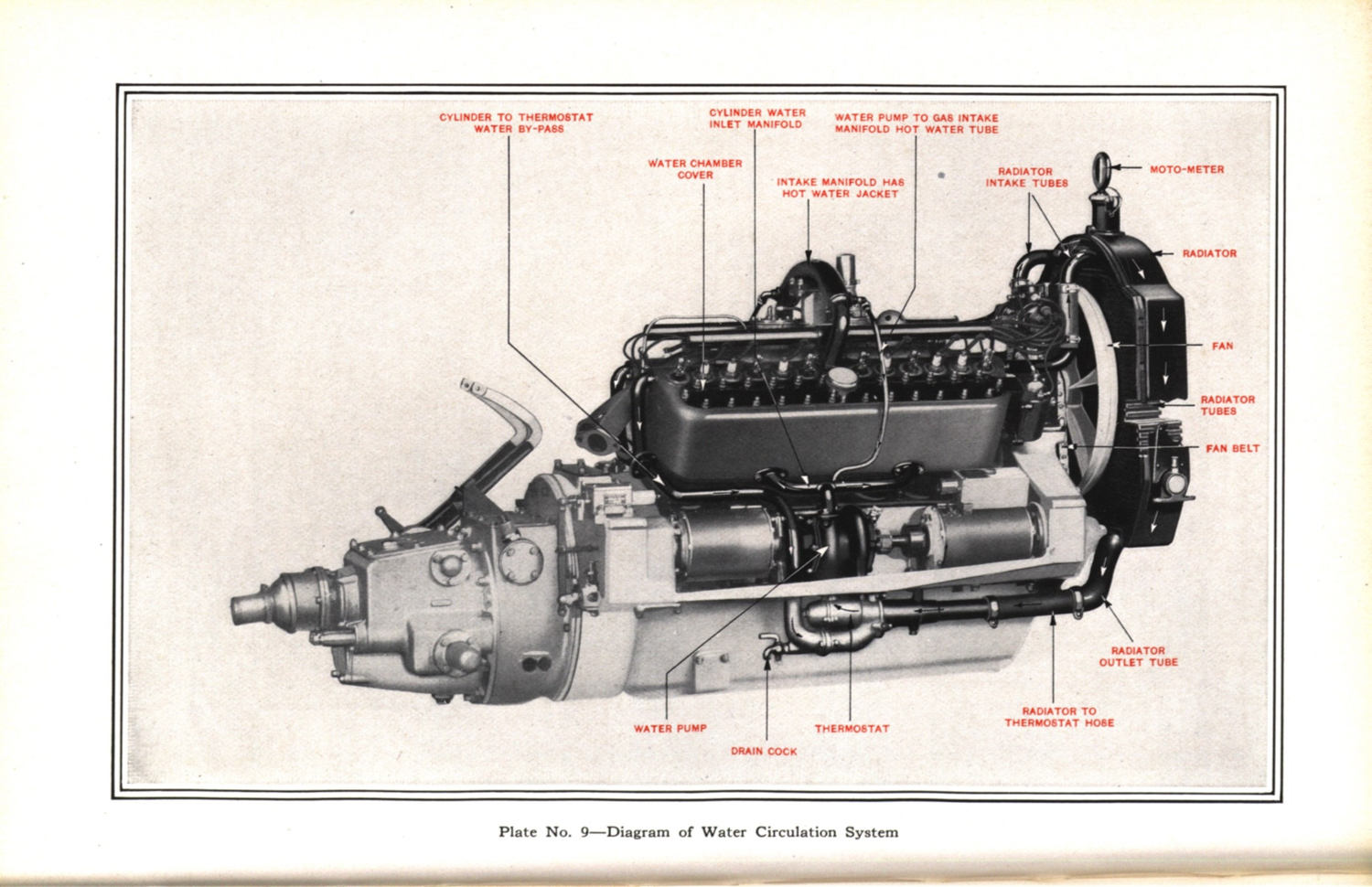

The Twin-Six was introduced May 1, 1915, the culmination of Vincent’s vision of the perfect automobile engine. The new 12-cylinder engine had two banks of L-head cylinders that were set at a narrow 60-degree V-angle (about seven inches narrower overall than a comparable 90-degree V-8), permitting the accessories to be attached to the frame, shielding them from road hazards and allowing the accessibility to the valves. (Later, Enzo Ferrari would be inspired by the Twin Six, designing his V-12 with a 60-degree V-angle as well). It was 424 cubic-inches with a bore and stroke of 3 by 5 inches, producing 85 horsepower at 3000 rpm. A separate cam for each valve eliminated the need for rockers, and all the valves were positioned inboard of the cylinder blocks. The engine featured a short and light crankshaft that ran on the main bearings. Normal oil pressure was improved to 20-30 psi increasing with engine speed.

Ignition was provided by a 120 amp-hour storage battery charged by a generator with a reserve dry cell battery, with an ignition timer and distributor containing a separate circuit breaker for each set of cylinders operated by a common breaker cam that were driven for synchronization at crankshaft speed. Additionally, there was a governor in the base of the timer housing that regulated spark advance with an auxiliary hand advance for high-speed usage. The transmission was now moved from Packard’s traditional location in the rear of the car to up front with the engine.

All this technology resulted in what Vincent called “Perfection in every way”, pointing out that Packard’s Twin-Six torque was “50 percent better than it would have been with a V-8, and 100 percent better than the six. Six pulses per revolution blend together so closely as to make it absolutely impossible to distinguish any pause between impulses, even at very low engine speeds pulling through traffic on up grades. The only thing I can liken to is the action of steam.”

The Twin Six makes its debut

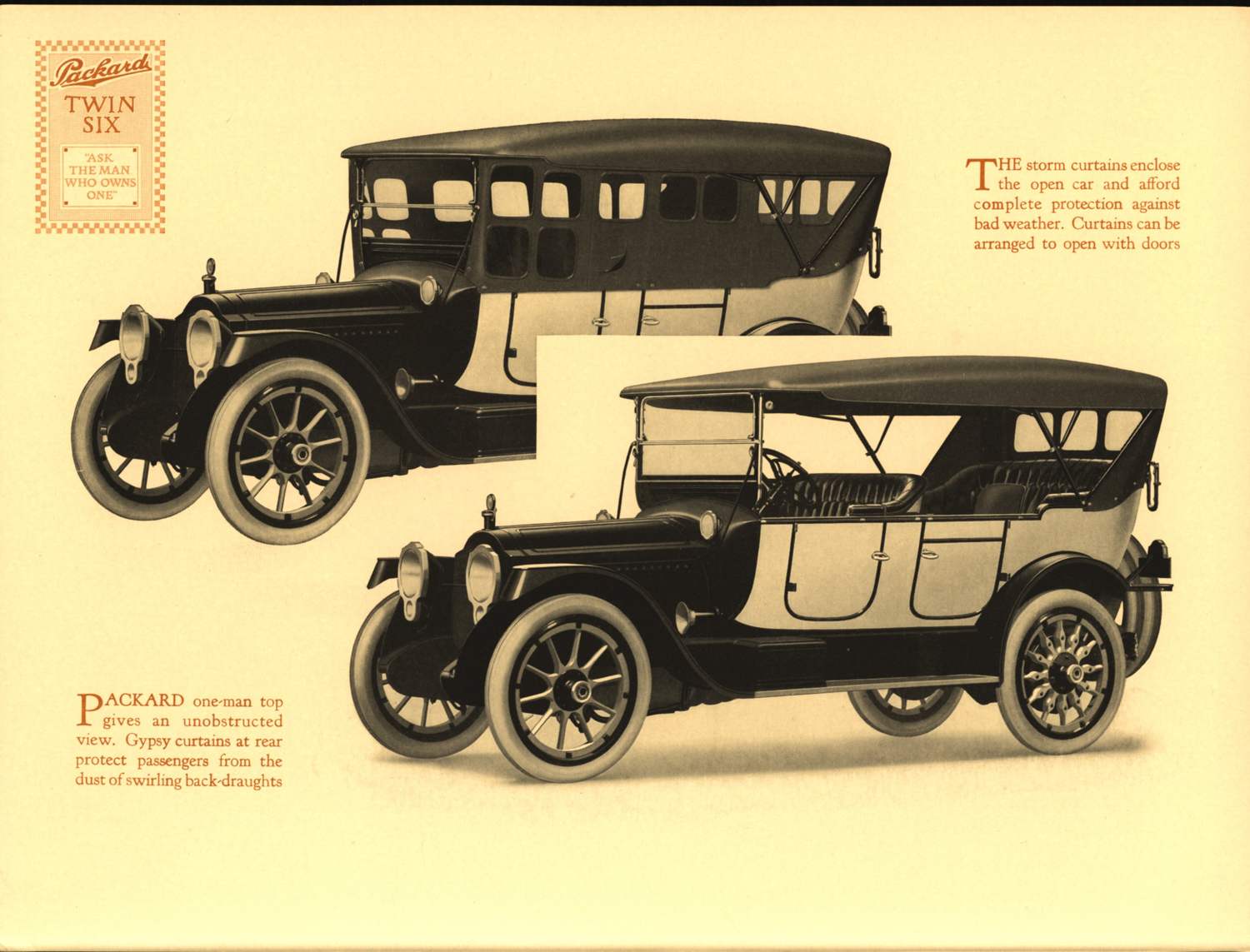

Debuting in May of 1915 for the 1916 model year, the Twin Six was available in two models with two different wheelbases: the 1-25 and the 1-35 featuring 125 inch and 135 inch wheelbases respectively. Initially, there were nine different factory body-styles (not including chassis only cars) offered for the 1-25, and eleven body-styles plus chassis only for the 1-35. List prices for the 1916 Twin Six had ranged from $2,750 to $4,800 for factory-bodied cars. Retail price of the 1-35 Seven Passenger Touring was $3150. The new model was a sensational success and sold well. Between 1917 and 1919, the company’s annual net profits were around $5.5 million. The Twin Six sales were huge compared to the six-cylinder cars they replaced, which were discontinued in September 1915. Packard constructed 3,606 1-25’s and 4140 1-35’s during 1915-1916, a remarkable total for such an expensive car. The Twin Six remained in production through June 1923 with various minor refinements, the most important being detachable cylinder heads in 1917. (The engine needs to be removed off the frame, filed down to replace the water pump on an early Twin Six according to one experienced owner). The engine also inspired, at least in part, the 12-cylinder “Liberty Engine” used in many Allied aircraft and tanks. Jesse Vincent contributed to the design of the Liberty along with Elbert John Hall of the Hall-Scott Motor Company.

A notable testimonial in the form of a letter to Illustrated London News was reprinted in The Packard : “For twenty years the Packard car has held the reputation of being in America what the Rolls-Royce is in England. Although not so many years ago one could say that it was comparatively easy for a car to be the best produced in America for that reason that, to use slang expression, it had ‘nothing to beat’, those days have gone by….

Certainly the Packard Twin Six has nothing to fear from comparison to anything on this side of the Atlantic. Indeed, I am not so sure but that comparison would be all to its advantage. One dislikes saying this, naturally, but it is nothing but the plain truth. Recently I had a day on the road with one…. It is not enough to say that the car is silent, or that it runs smoothly; when we are talking about the ‘Twin Six’ we have to find some other manner of describing these essential qualities. The only approach I can make to it is that the twelve cylinders give such a near approximation to uninterrupted impulse that there is no sense of any mechanical effort.”

Even though Packards were too large and too heavy to be considered true performance cars, in July 1915, racecar driver Ralph De Palma lapped the Chicago Speedway in a Twin Six touring car at an impressive average speed of 72.7 mph over a 10-mile, 5-lap heat with the windshield up and the top down. De Palma then added five passengers and ran the same laps at 69.8 mph!

Mr. Lamb buys a Packard

Our feature car, a 1916 1-35 Twin Six Seven Passenger Touring, was purchased new from the Chaplin Motors / Packard Motor Car Company, located at 495 Forest Ave in Portland Maine, by Thomas Avery Lamb (TAL) who lived about 25 miles away in South Casco, Maine. Mr. Lamb owned the big Packard for eight years, driving it sparingly to get around town and for leisurely drives in the beautiful Maine countryside. Mr. Lamb passed away in 1924 and the car was handed down to his daughter, Mary Lamb Riley, who also lived in South Casco. The TAL Twin Six would remain with Ms. Riley and then her daughter, Marjorie Lamb Riley for decades. The car was retired and stored for 48 years in the same protected and undisturbed building that her grandfather, TAL, had kept it in.

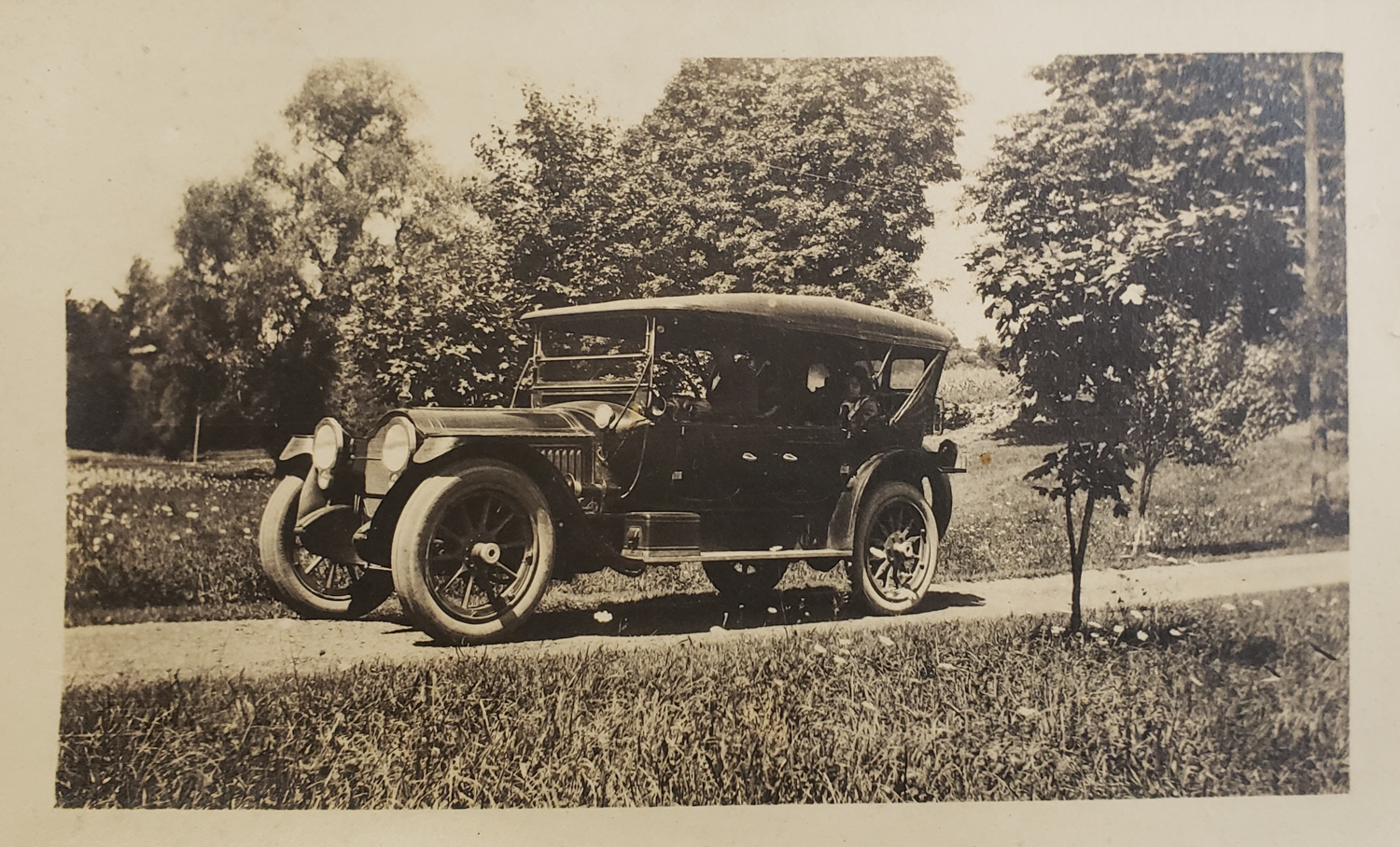

In 1972, after having spent nearly her entire life in ownership of the Packard, Marjorie Lamb Riley, at age 60, decided to sell the car. The buyer was South Casco resident Alicia Ash. The big Packard was still unused and undisturbed at the time of purchase. Ms. Ash paid a lofty $40,000 for the car, which was an incredibly high price at the time. An early black and white photo was given to Ms. Ash at the time of the sale of the Packard with the words “Dad’s car!” written on the back. The photo shows Marjorie Lamb Riley, granddaughter of Thomas Avery Lamb, seated in the back seat.

Alicia Ash kept the Packard for about four years before selling it to legendary pioneering collector Richard C. Paine, brokered through Willard E. Pike of Standish, Maine. The sale price was $31,000, which was still an extravagant price at the time. Paine was responsible for amassing one of the finest collections of classic cars ever. His collection included such significant cars as a 1937 Alfa Romeo 8C 2900B Corto Spider and a 1938 Bugatti 57SC Corsica Roadster. Recognizing and appreciating the uniqueness of its originality, Paine kept the car in his personal collection located in Seal Cove, Maine, but never displayed it at car shows. Few collectors at the time had such an appreciation for original, unrestored cars, no doubt motivating him to acquire the Packard regardless of the price. His legacy lives on in the form of the Seal Cove Automobile Museum. Paine kept the Twin Six until 1988 when he sold it to Mr. Charles LeMaitre of Hardwick, Massachusetts. Mr. LeMaitre commissioned the task of bringing the Twin Six to life after being in hibernation for decades to Howard Lane Restorations in Hardwick, Massachusetts. Interestingly, previous owners of the Packard never attempted to start it up. After cleaning the fuel system, checking the ignition and filing the points, and replacing all the fluids, the big Packard fired to life and ran smoothly after sitting since parked in 1924 when its original owner passed away. LeMaitre also never publicly displayed it and subsequently sold it to its current owner in 2018. Since the current owner’s acquisition, it has appeared on the lawn at Pebble Beach, as well as the Ironstone Concours in Murphys, California.

In an incredible state of preservation

Today, Mr. Lamb’s old Packard has less than 20,000 miles on its odometer and is in completely original, unrestored condition. The extreme originality of this car is stunning. Tall and ghostly, the massive black touring car has a commanding presence. The color finish on the body, coated with varnish from the factory is intact and believed to be original, now dull and cracking from over a century of age, has an intriguing patina. The delicately thin gold pinstripe is still intact, as well as the original owner’s initials T.A.L. on the front doors.

One of the most remarkable features of this car is the folding top. All the wood, snaps and soft top material is original with a brass plaque identifying it as a “Golde-Patent ‘One-Man’ Top, license No. 58092” The top is still soft and pliable enough to be useable, which is amazing. The original accessory set of 10 side curtains with “Eisenglass” are still with the car and in excellent condition, having been found stowed under the rear seat in 2018.

Information obtained from the car’s current caretaker regarding the Eisenglass is as follows: “The rarity of original cannot be overstated. It has long been debated what original Eisenglass was made out of (or even its spelling) with some believing it was made of fish bladders, while others believed it to consist of a composite made from Mica. The truth, as we know first-hand, is that original Eisenglass from this period is made from cellulose nitrate, a highly flammable and typically short-lived material. Tests were performed in the form of burning a small fingernail sized piece found in the bottom of the compartment where the find was made and it was confirmed that not only did the piece burn away like gunpowder as one would expect with the burning of cellulose nitrate, but also the scent of Camphor could be smelled, another speculated component of the composite. It is easy to see why not much of this early, plastic-like component used on early automobiles exists today and makes its addition to the originality of the TAL Twin Six, in such a splendid condition, all the more important towards an overall presentation of exceptional originality.”

The interior of the car is no less impressive in its condition and originality. The black leather seats, including the two collapsible jumps seats are in excellent condition with some patina, as are the leather door panels. The paint on the wood dash and the top of the doors are still in good shape and even the sisal over-rugs remain in nice condition. The factory cabin lights still function properly as well.

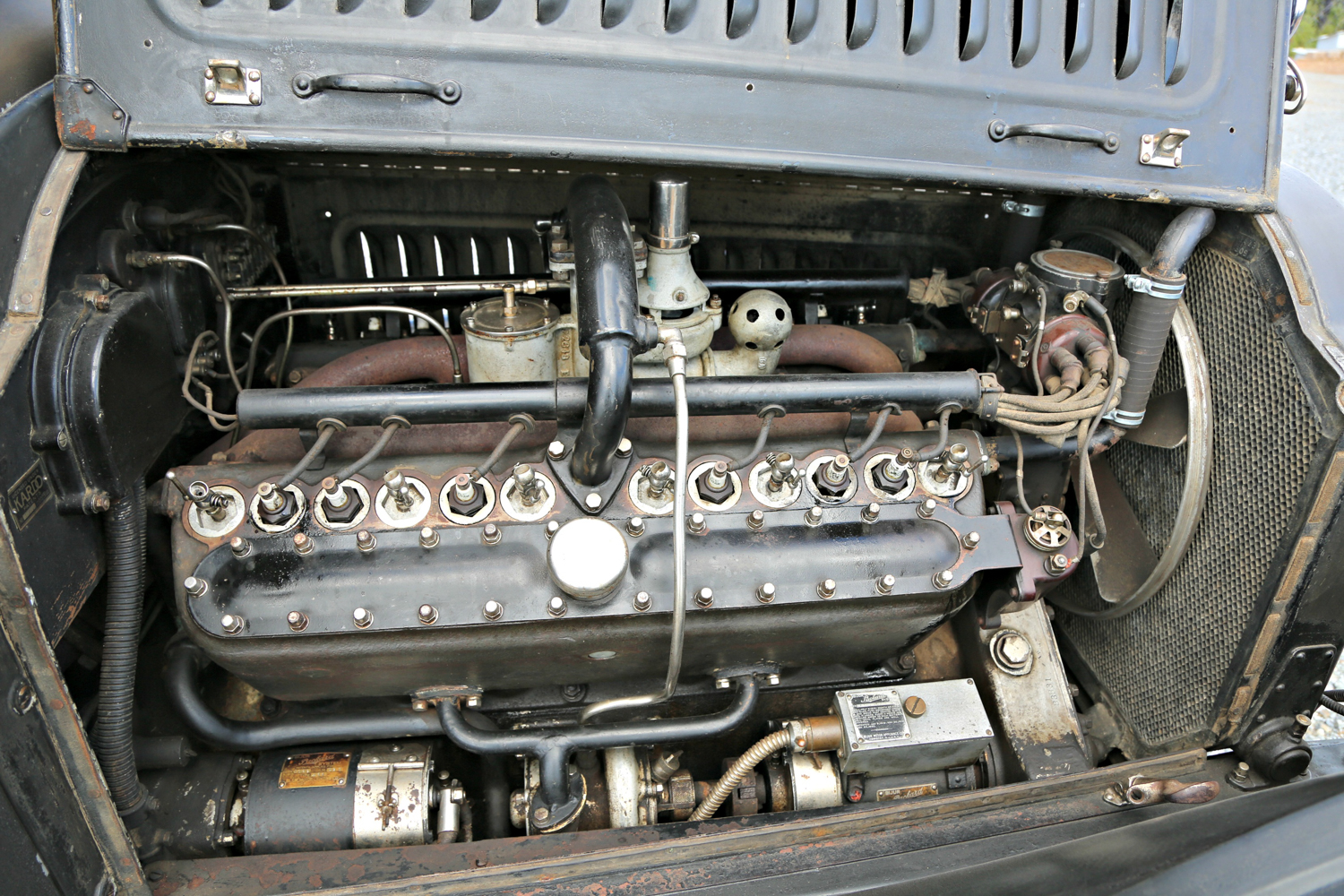

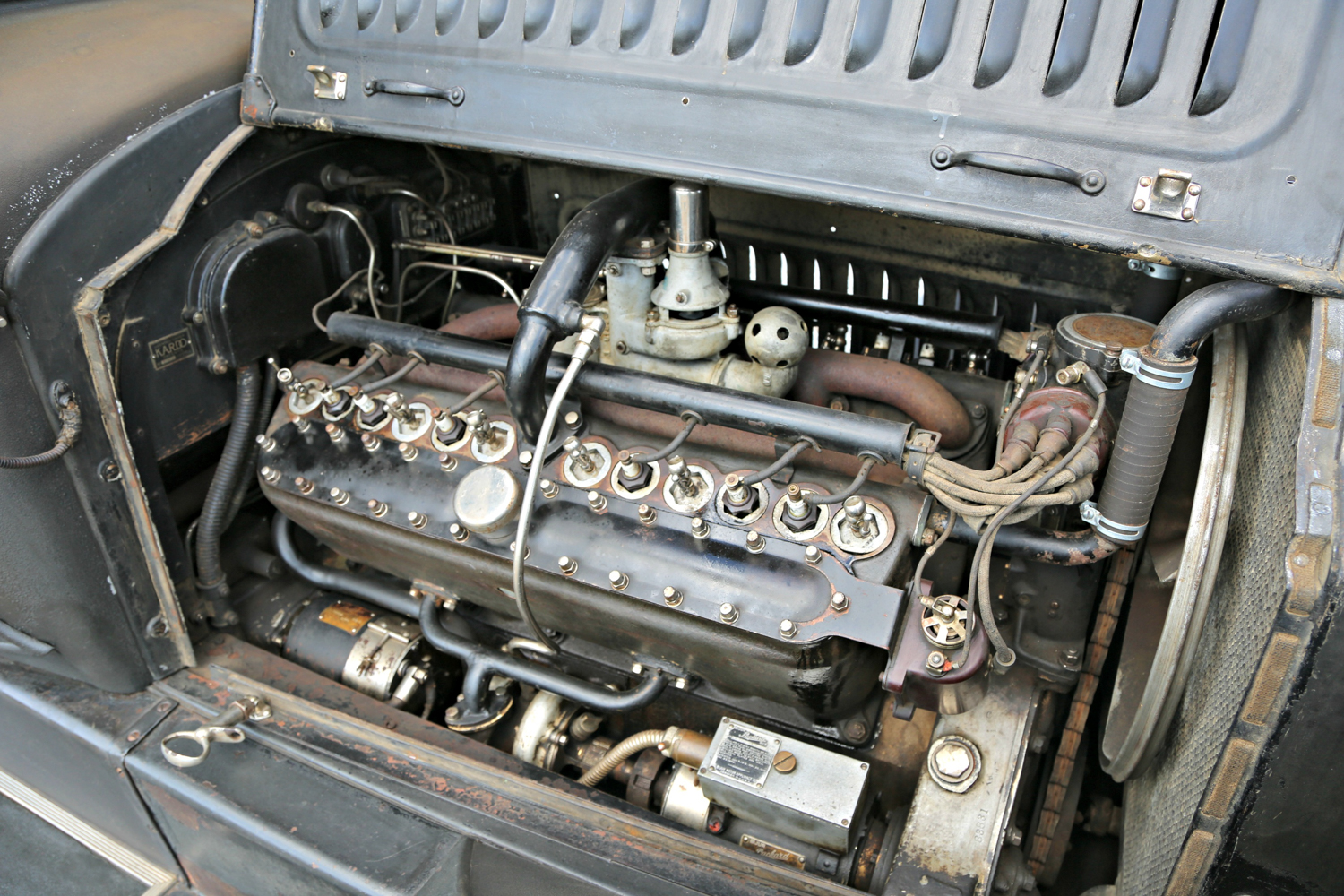

Lifting the hood reveals an exceptionally complete and undisturbed engine compartment with original components, emblems, decals, patent markings and surface coatings intact. The original belt is present, as well as the triangular leather pads for the corners of the engine bay side panels that protect the metal, are still intact and performing their intended function. The engine is impressive in size and design and a thrill to see in this state of originality.

I received the rare privilege of going for a short ride in this remarkable time machine. The big 12-cylinder mechanical-wonder started easily after I climbed up into the front seat where a commanding view awaited me. Immediately I was in awe of how luxuriously smooth and quiet the engine was. No put-put, chug-chug here like many cars of the era. We drove around a corner and up a hill with ease, with plenty of power and torque. The clutch was remarkably smooth allowing for it to run through its gears effortlessly. At idle, the car was as silent as it was at speed, with only the sound of air being drawn in from the carburetor when the throttle was depressed.

Spending time studying and riding in this Packard, one can only be in awe of not only its amazing originality, but of the century-old technology of this machine. Big and powerful, yet silky-smooth and silent in operation, the Packard Twin Six is truly a mechanical marvel.