Back in 1982, I bought a 1940 Packard coupe and spent the next couple of years restoring it. Once I had the engine extracted, I decided, upon sober reflection, to have a pro do the rebuild. The guys at the parts house referred me to classic car expert Paul Schinnerer in Long Beach, California. He did a great job, and even helped me set the engine back in the chassis.

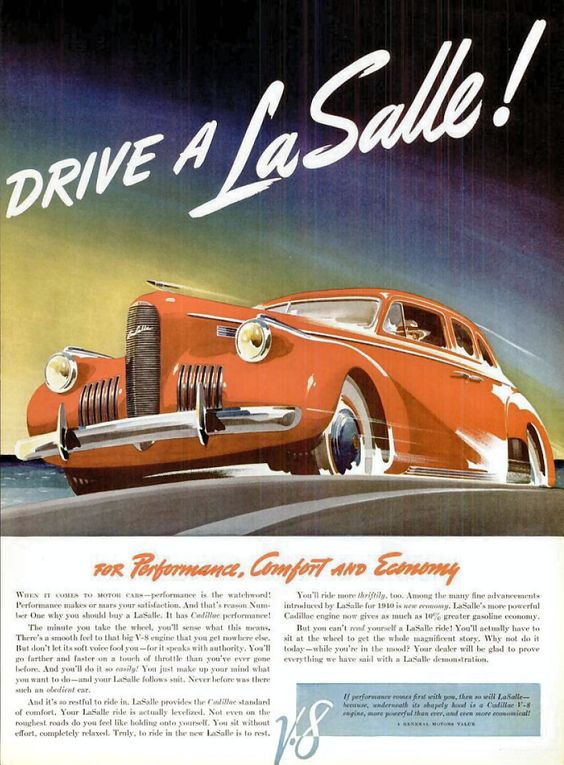

He drove over to my house in a 1940 LaSalle Series 52 Special coupe, and I fell hopelessly in love with it. It’s sensuous curvy body, distinctive grille, and the throaty rumble of its big V8 were magic. Paul also has two 1930 Cadillac V16 classics that are masterpieces in their own right, and each is worth more than my house, but Paul’s LaSalle coupe was like a Brancusi sculpture on wheels. It was shear beauty from any angle. I told Paul at the time that if he ever ever wanted to sell it to give me a call.

Thirty-six years later Paul called me. I was 7,000 miles away, but I arranged a wire transfer then and there without even consulting my spouse. That would normally have been a very dangerous mistake, but she knew full well how much I loved that car, and that era of design in general.

I have had a special love for the ’30s era cars almost from birth. However, to me the most beautiful of them are not the great early ’30s classic Packards, Duesenbergs, Marmons and Cadillacs, as magnificent as they are, but the later cars with what was called streamlined styling. The classics are stunning in their own right, but in a different genre.

Auto styling gained more critical importance in the 1930s because of the depression. Engineering all new cars proved prohibitively costly with the economy in such a shambles. However, making this year’s model look new and exciting, and making last year’s model look like last year’s model, was a much less expensive way to go. This strategy was soon referred to as designed-in obsolescence, because it made an automaker’s offerings look new even though they were essentially the same car with a new hair do.

Buying Paul’s LaSalle was actually nothing short of a lifelong dream fulfilled. My father was in the navy during World War II and was stationed at Treasure Island, near San Francisco. I was four-years old at the time, and my mother and I stayed with my aunt Dolly nearby in Berkeley, in order to see him off on a voyage that ultimately took him to Iwo Jima, Okinawa, and finally Tokyo Bay.

Aunt Dolly was well off, lived in a big house, and drove – you guessed it – a 1940 LaSalle. I found cars exciting even then, and to me it was the most beautiful car in the world. I wanted one from that day on. I was kind of a weird kid. Most of my contemporaries swooned over Corvettes, Thunderbirds and Eldorados, but I lusted after Art Deco-era Cords and LaSalles.

Even though Shinnerer’s LaSalle had only done 7,000 miles in the last 15 years, it started easily as soon as fresh fuel got up to the carburetor. I had learned much of what I know about car care and restoration from Paul over the years and he became a good friend. He is a well-known restorer, electrical whiz and mechanic in his own right, and he had taken excellent care of what was a beautifully preserved original car. It is not perfect, but after 80 years it is in extraordinary condition.

The mostly original interior smells the way cars of the era did. It is an mélange of old wool upholstery impregnated with crankcase and fuel aromas, plus a redolent residue of cigarette smoke. Sitting in it, I am suddenly back in time with my folks. My Pop is puffing on a Lucky Strike, while mom is making sure the netting on her hat is properly arranged.

The steering wheel is huge, as are the pedals on the floor. I have plenty of headroom for driving even with my 1940 Humphrey Bogart fedora at a jaunty angle. The dash is way up in front of me, and I have plenty of room under the steering wheel to move about.

I pull the column shifter into gear. The linkage is still tight and precise. This car is big. Looking out over acres of noble, hood with its pointed prow, I see that stylized nose ornament in the distance and aim it in the direction I want to go. I wrestle with the big steering wheel while the car is barely rolling, but once I am lined up I give it the gas and its later replacement 346-cubic-inch, 150 horsepower, flat head V8 engine comes to life with alacrity. It is in fact a tank engine. World War II Stuart tanks used two of these big Cadillac mills to power them.

Turns out that in the early ’50s a previous owner of Paul’s LaSalle replaced its tired 322-cubic-inch V8 with a war-surplus tank engine, of which there were plenty after the war. In fact, there is still a brand new one listed on eBay as I write this. It is the same block as the Cadillac automobile engine on the outside, but is punched out an extra eighth of an inch, and has better bearings and metallurgy than the original.

Another reason for this approach was that having lots of torque at the bottom end would allow you to drive around town in second gear, thus avoiding having to shift gears constantly. In this LaSalle coupe, you really don’t need high gear until about 45 miles per hour; and that was the speed limit on Southern California’s first freeway — the Pasadena — in 1940 when it opened. High gear will take you up to 70 for easy cruising.

The story of the LaSalle marque began when Harley Earl — arguably the godfather of modern auto design — was hired away from Don Lee Cadillac’s custom body section in Los Angeles to design a new smaller sportier companion make for Cadillac in 1927, and was given only four months to do it. He borrowed heavily from the styling of the Hispano-Suiza of the time, and added some handsome flourishes of his own. The result was a huge sales success.

The LaSalle moniker was a logical follow-on from the Cadillac brand, which was named for French explorer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, who founded Detroit. So to continue in that vain, the new LaSalle was named for Rene-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle who had explored the Great Lakes region a couple of centuries before.

Also, during the pre-war period Paris was the center of fashion, style and culture for the western world, and many Americans considered French design to be the ultimate. Cadillac recognized that regard for all things European when they made Earl head of design for General Motors and gave him his own styling section called the Department of Arts and Colours, with the British spelling being an intentional nod toward the continent.

LaSalle was Cadillac’s companion make, though it lasted longer than the short-lived Viking that was Oldsmobile companion make from 1929 until 1931, and the Marquette for Buick in 1930 that lasted just one year. These additions to the General Motors lineup were added during the heady boom times of the late ’20s, just in time for the stock market crash and the great depression. Pontiac was the exception. It began as a companion make for Oakland in 1926, and wound up consuming its host in 1933.

Actually, LaSalle lasted longer than most GM companion makes; but it too would finally go the way of the others in 1940, albeit due to rather unique circumstances. In fact, LaSalle almost went down along with the Viking back in 1933. But the problem was LaSalle’s success, not its failure, but more on that later.

In fact, LaSalle was only saved for 1933 because Harley Earl was wandering around the design department one night looking at what his designers were doing, and spotted some sketches done by Jules Agramonte that were revolutionary. They drew directly upon the British streamlined beach racers, and were beautiful and exciting. They showed low slung streamlined machines with speed line creases and highlights down their hoods and fenders from front to back, and sleek swept back two-piece windshields.

Earl waited until the end of the new model presentation to the executives in 1932 to present Agramonte’s work as the car General Motors was not going to build in 1933. It was so handsome and exciting that management changed their minds then and there, and the LaSalle marque was saved – at least for the time being.

The design objective that went into the LaSalle was to make it a trendsetter, with new fresh and exciting looks every year. As a result, design ideas were tried on the LaSalle first, and later adapted to the Cadillac and other GM automobiles.

Later in the decade, 23 year-old stylist Bill Mitchell’s prototype for the 1938 LaSalle was actually commandeered to become Cadillac’s Sixty Special, and that began the death spiral of LaSalle, even though most of GM’s management proudly drove them rather than Cadillac’s other offerings.

The marque’s eventual demise was also partly because Packard debuted their junior series mass-production model 120 in 1935 and it was a run away success. In fact, it was so successful that Packard’s best year ever was 1937, when other car companies were collapsing into bankruptcy.

The 120 was in no way comparable to the big handcrafted senior Packards, though they shared similar styling and the Packard badge. The 120 sold so well, in fact, that in 1937 the new junior lineup included an even less expensive six-cylinder model that made it possible for people of modest means to own a Packard.

Unfortunately, in the end, the tremendous success of Packard’s junior models resulted in Packard retreating from the high ground for a bigger position in the mid-priced field. And that caused management at Cadillac to go in the opposite direction as the depression was winding down by making the mid-priced LaSalle the entry level Cadillac and dumping the LaSalle marque all together in 1941.

It was all marketing hocus pocus, but in the end Cadillac survived and Packard didn’t. Of course, the fact that Cadillac had General Motors to back it up in the lean times helped a lot too, and there were other post-war mitigating circumstances that entered into it as well.

As an owner of both a 1940 LaSalle and a 1939 Packard junior series 120, I can say that in some ways they are polar opposites. Packard went for conservative classic elegance, and LaSalle went for flash and dash. Also, LaSalle altered its look every year to be a trendsetter, but Packard’s styling was conservative and evolutionary. If you were a banker you drove a Packard, but if you were a movie star like Hedy Lamar or Katharine Hepburn you drove a LaSalle.

In 1940, Packards still had running boards, and hoods that were hinged down the middle and opened at the sides, but LaSalle had a one-piece clamshell hood. And though you could still order a LaSalle with running boards, most buyers didn’t. Doing away with running boards allowed the LaSalle to sit lower, and made the interior roomier. Also, Packard still had a big round speedometer and wood graining on the dash and window reveals, but LaSalle’s dash and trim were painted in restrained colors with Streamline Moderne integrated styling.

There were two series of junior Packards in 1940, which were the 110 and the 120, and there were two series of LaSalle, as well. The lower priced LaSalle was the series 50, which was a bit smaller and more angular looking, and the top of the line was the series 52 with the Torpedo Body, which was rounder and bigger. The series 50 looked more like the 1939 models, and the series 52 looked more contemporary, though both had the same running gear.

Packard’s smoothness and silence as a result of its inline engines can’t be topped, and surprisingly the Packard Super Eight of that year was the fastest production car available. But Packards were available with Borg Warner overdrive, which gave them a better top end cruising speed.

However, the bottom end and mid-range oomph of the LaSalle and Cadillac V8 engines is impressive, and its transmission is smooth, silent and nearly bulletproof. Packard’s steering and front suspension was so good that Rolls-Royce copied it, but the LaSalle while excellent, is a bit more of a handful until you get it rolling.

You could get air conditioning in the Packards, but Cadillac didn’t offer it until a year later. On the other hand, blinkers were built into the LaSalle, but were an extra cost option on contemporary junior series Packards. Both marques had their virtues, and both provided top quality reliable and long-lived transportation, so in the end, it essentially boiled down to the image you wanted to project. And while both cars are very comfortable for touring, the LaSalle is roomier.

Also, both Cadillac and Packard were at a pivotal point in 1940. Cadillac had jettisoned its V12 years before, and 1940 was the last year for Cadillac’s V16. Packard had jettisoned its V12 in 1939, but both retained their big eights, though Packard’s was inline, while Cadillac stayed with its traditional V configuration. Both companies did very well during World War II, helping with the war effort. But Packard never quite regained the prestige it had before the war, and poor management decisions spelled the end of the venerable old company by the late ’50s.

I love both marques, although for long distances and higher speeds, I might choose the Packard thanks to its optional overdrive. However, for showing up at stylish events and for red light races, I would choose the LaSalle. It is sad that neither brand survived in the end despite — or in spite of — all the marketing ploys and jockeying for market position. The so-called companion make outsold its host by nearly double in 1940: 24,133 La Salles to 12,984 Cadillacs.

The bean counters at GM concluded that it cost almost as much to build a LaSalle as it did a Cadillac, but the LaSalle commanded a lower price, which meant less profit for the division. LaSalle’s sales success meant fewer Cadillacs were purchased, so the companion make was eating into company profits from both ends.

There is no production car made today that makes such a dashing sophisticated statement as a 1940 LaSalle in my opinion. And, save for Rolls-Royce, there is nothing that matches the prestige of a Packard.

1940 LA SALLE 52 SPECIAL COUPE SPECIFICATIONS

PRICE Base Price: $1,380

ENGINE Type: L-head V-8; cast-iron block and cylinder heads Displacement: 322 cubic inches Bore x Stroke: 3.375 x 4.50 inches Compression Ratio: 6.25:1 Horsepower @ RPM: 130 @ 3,400

FUEL SYSTEM: Carter WDO 423s two-barrel downdraft carburetor

ELECTRICAL: 6-volt; positive ground

TRANSMISSION: Three-speed column-mounted manual; synchronized second and third gears, single dry-plate 10-inch clutch Ratios: 1st: 2.39:1 2nd: 1.53:1 3rd: 1.00:1 Reverse: 2.39:1

DIFFERENTIAL: Hotchkiss; hypoid gears; 9-3/8 ring gear Gear ratio: 3.92:1

STEERING: Saginaw worm and double-tooth roller

Turns, lock-to-lock: 4.1 Ratio: 19:1 Turning Circle: 42 feet

BRAKES Type: Four-wheel hydraulic; dual-servo, self-energizing, manual activation Front/rear: 12-inch drums

CHASSIS & BODY Construction: Steel body, X-member frame with deep side rails Body Style: Two-door coupe Layout: Front engine, rear-wheel drive

SUSPENSION Front: Independent; coil springs, double-acting hydraulic shocks, stabilizer bar

Rear: Live axle; eight-leaf semi-elliptic springs, double-acting hydraulic shocks, stabilizer bar

WHEELS & TIRES Wheels: Pressed-steel: 16 x 4.50 inches Tires: Four-ply 7.00-16

WEIGHTS & MEASURES Wheelbase: 123 inches, Overall Length: 211 inches, Overall Width: 78 inches, Overall Height: 67 inches, Front Track: 58 inches, Rear Track: 59 inches, Shipping Weight: 3,810 pounds

CAPACITIES Crankcase: 7 quarts Cooling System: 25 quarts Fuel Tank: 22 gallons Transmission: 2.5 pints

PERFORMANCE 0-60 MPH: 15.5 seconds

PRODUCTION 1940 Series: 52 coupes 3,000