We are very proud, this month, to be the first magazine to bring you a test drive of the rare Lancia D50 – in this case, one of the four cars exactingly recreated from original factory drivetrains. Complementing this rare insight into one of history’s most identifiable Grand Prix cars is a fascinating look into the mysterious final days of one of the D50’s most loved and noted pilotos, Alberto Ascari. During the ’50s, Ascari was quintessential hero material – young Italian boys, including one named Mario Andretti, dreamed of growing up to one day be like Ascari.

Interestingly, while it is not always well known, even young Alberto himself dreamed of growing up to be a racecar driver like the great Ascari; in his case, it was his famous father Antonio.

Antonio Ascari was a prewar Italian racing legend who started to compete literally in some of the first organized Grands Prix to be held in Europe. He got his racing start as early as 1911; but World War I put his racing aspirations on hold until 1919 when he began making a name for himself in major Italian hillclimbs, eventually moving on to race the hallowed Alfa Romeo P2 in 1924.

When compared to today’s homogenized, sanitized, politically correct world of Formula One, the elder Ascari appears to not only hark from a different era, but an entirely different sport! One of the most striking examples of these differences was Antonio’s unusual victory in the first Belgian Grand Prix, held at Spa in 1925.

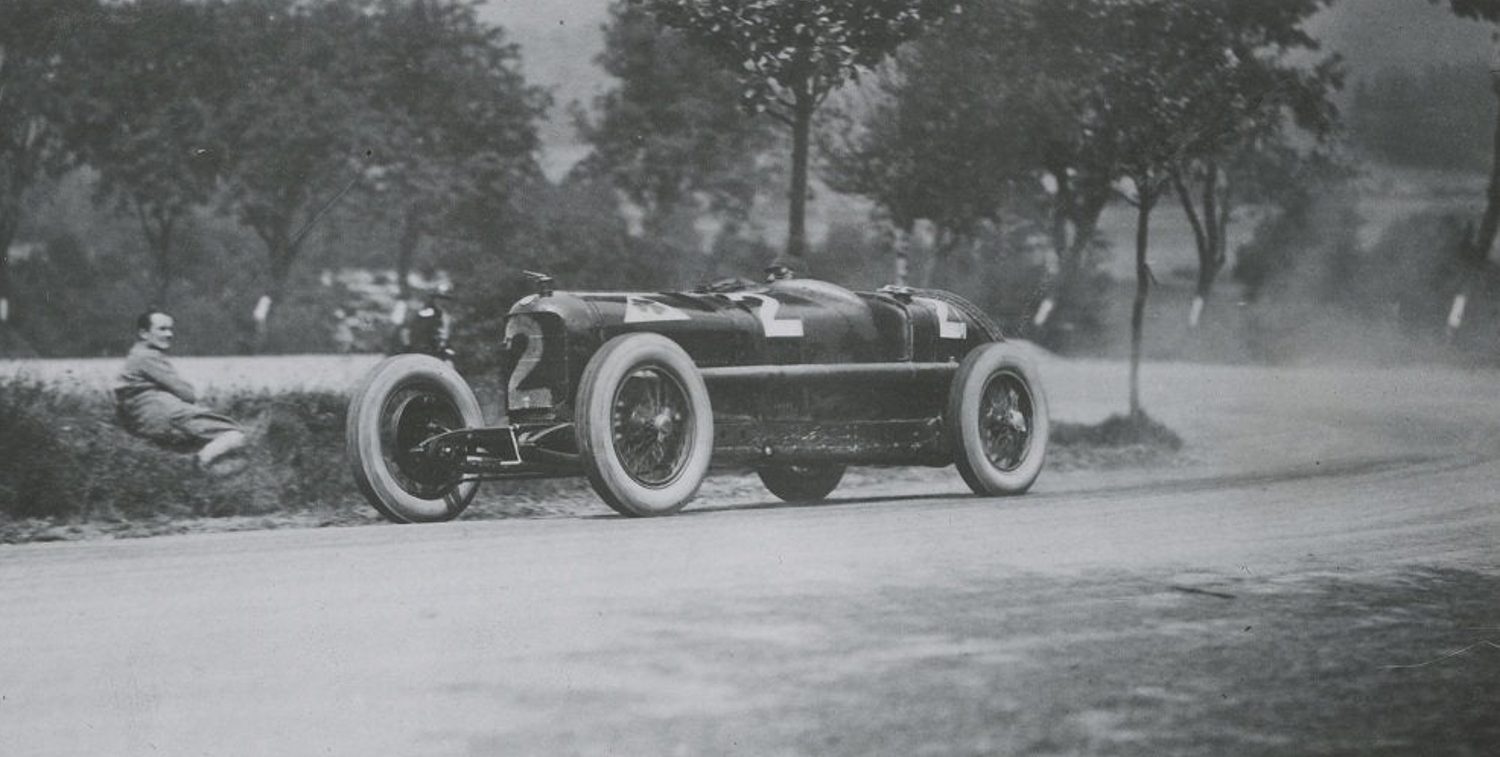

Grand Prix fever was spreading like wildfire throughout Europe in the mid-’20s and so it was perhaps no surprise, when it was announced that Belgium would host its own round at Spa (known as the European Grand Prix), that French nationalism and expectations would be running high. However, come race day the 12-car field, which was supposed to include a number of Sunbeams and Guyots, had been reduced to a scant 7-car grid consisting of only four Delages and three Alfa Romeos. Any guesses whom the crowds were rooting for?

On the French side, Gallic pride was being upheld by René Thomas, Robert Benoist, Albert Divo and Paul Torchy driving for the Delage team, while the “cross-town” rivals from Alfa Romeo were represented by the prewar dream team of Antonio Ascari, Giuseppe Campari and Count Gastone Brilli-Peri.

As the green flag fell, and the tiny field took to the first of 58, 8.76-mile laps of Spa, Ascari led from Campari, Benoist, Brilli-Peri, Divo, Torchy and Thomas. However, no sooner did the race begin than the Delage team began to suffer retirements. In the first lap, it was Benoist with a leaking fuel tank; then on lap four, Torchy stopped with a misfire that eventually sidelined him. By lap seven, there was another French slap on the face when Thomas’s Delage caught on fire, forcing the driver to attempt to beat out the flames with his bare hands. With not even half the laps completed, the race was already down to four cars, three of which were Alfa Romeos. The natives were indeed getting restless.

Soon the French odds were temporarily improved when Brilli-Peri retired with a broken spring, but the coupe de grace was delivered when the lone remaining Delage of Divo retired with mechanical problems. This left only the two Alfas of Ascari and Campari on-track and, as might be expected, the Belgian crowd was none too pleased by either the boring procession that the race had become or by the fact that there were no longer any French cars competing. With nearly 250 miles of the 500-mile race distance still left to be run, the crowd began to boo and heckle the Alfa Romeo driving duo each time they completed another circuit. In fact, the derision became so bad that Alfa Romeo team manager Vittorio Jano decided that he would personally teach the unruly crowd some manners.

Jano called in his drivers to the pits as he had his crew lay out a lavish picnic lunch in the middle of the pitlane! The drivers came in, got out of their cars and sat down for a delightful mid-day repast as the mechanics slowly went to work on polishing the cars for the post-prandial resumption of racing. The Belgian crowd was mortified.

After satisfying their appetites (and Jano’s ego), Ascari and Campari got back in their cars and resumed their two-man Grand Prix with Ascari going on to a healthy 22-minute margin of victory. Can you imagine Frank Williams bringing in the boys for a ploughman’s lunch during this day and era?

Unfortunately, Ascari didn’t have long to bask in his Belgian victory, as you’ll read in “The Ascari Mystery”; he was killed in the next event, the French Grand Prix, leaving a tremendous racing legacy for his son Alberto to continue – with both eerie and tragic consequences.