Magazines are a funny thing. You hold in your hand the August issue, but you’re likely reading it in July and I’m writing this column in May! Go figure. It’s no wonder I can’t keep straight what month it is…not to mention what day it is!

On the 8th of May, I was reminded of the fact that this day marks the 20th anniversary of Gilles Villeneuve’s death while qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix. I have to admit that it saddens me every May, when I think about it. You see, Villeneuve was one of my all-time racing heros.

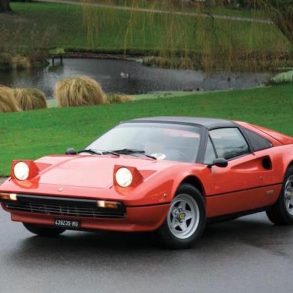

In reality, I have many racing heroes, Fangio, Nuvolari and Gurney all leap immediately to mind. But there was something about Villeneuve – his on-track performances could literally take my breath away. I first saw him race at the Long Beach Grand Prix in 1978 and he was like nothing I had ever seen before. His level of determination and commitment permeated the track like high octane fumes. He drove like a man possessed, because he was a man possessed. His Ferrari teammate in 1979, Jody Scheckter, once said of Villeneuve, “Gilles was always wanting to prove himself, for every lap. I never knew him to say ‘I will take it easy now.’ It was always the maximum.” Formula One champion Nelson Piquet once remarked, “He’s somewhat crazy, but surely a phenomenon. He’s able to do things which nobody else could achieve.” While historians and his contemporaries have always debated whether he was a miracle or a madman, they all could agree on one point – he was exciting. Seems like a long time since that word was used in the same sentence as Formula One. FIA president Max Mosley says F1 is more intellectual now – a chess match. When was the last time you saw a chess match on ESPN?

In contrast to today’s multimillion dollar parades, Villeneuve made each Grand Prix an edge-of-your-seat cliffhanger. In the four short years that he graced the Formula One grid he put in some of the most exhilarating and memorable drives of all time. Who could forget his electrifying duel with Rene Arnoux in the 1979 French Grand Prix, where the two raced side by side for the last several laps with wheels interlocked the entire way. Every now and again, I watch a tape of those closing laps and it still gives me butterflies in my stomach, 20 years and 100 viewings later.

But sadly, as the saying goes– the candle that burns twice as bright, burns twice as fast. On May 8, 1982, Villeneuve went out in the final moments of qualifying for the Belgian Grand Prix at Zolder, trying to regain the pole from teammate Didier Pironi, when he collided with the March of Jochen Mass on a cool-down lap. Villeneuve’s Ferrari was catapulted skyward and cartwheeled down the track, disintegrating with each impact. His body was found 50 meters away from the wreckage, the force of the impact so severe that his helmet was knocked off in the crash. The fiery Canadian from Quebec was later pronounced dead at a local hospital.

Villeneuve’s death stunned the F1 community. So moved was Enzo Ferrari upon hearing of Villeneuve’s death that he openly wept, commenting that Villeneuve’s “…fatality has deprived us of a great champion – one that I loved very much.”

Twenty years later, I look back at the circumstances that led up to his death and I’m startled by some of the parallels to recent events in F1. Part of Villeneuve’s fire to regain the pole that fateful day was a burning desire to beat his teammate – in fact, to punish him. Villeneuve and Pironi had been both teammates and close friends up until the preceding race at Imola. In what is now classic Ferrari tradition, team orders had dictated that whoever led the race with 10 laps to go, would be the winner and would not be challenged by his teammate. Villeneuve led the race with 10 laps to go, and so backed off to save his car, only to be passed by Pironi and pipped for the victory. It was obvious on the winner’s rostrum that he was furious and in fact the two friends never spoke again. The next race was Zolder and Villeneuve intended to be number 1, at all costs.

In many respects, those team orders created a set of circumstances that may have contributed to his death. In retrospect, it is ironic that another set of Ferrari team orders in 1979 forced Villeneuve to hand over victory at Monza to Scheckter, thus gifting the South African the championship that Villeneuve could have claimed for himself. These calculated “chess-like moves” seem all the more salient this month, in light of the furor over the Ferrari team orders that recently forced Rubens Barichello to hand over the Austrian Grand Prix to Michael Schumacher.

Recalling this anniversary makes me realize how much I miss Villeneuve – it also makes me realize how much I miss F1 races that are riveting to watch.