The genius of Colin Chapman is evident in every one of his cars. Each of his creations were uniquely endowed, not only with clever engineering, but a special blend of design and mechanical innovation that seemed to illude virtually all other manufacturers, or at least be years ahead of them. Chapman didn’t work alone, but his upstart staff of college student apprentices and rogue engineers were grossly underfunded. Budgets were often non-existent, and much of their innovative methods and processes were real-time experiments as production moved forward with concurrent “Ah-hah” moments, using customers to test the limits of their cars. Gathering steam as an upstart volume manufacturer, Lotus had developed a few cars to modest success, but with just five years of shoe-string resources at hand and operating out of a makeshift former horse stable, in 1957, Lotus Cars would bring forth one of the most advanced cars of the decade, the Lotus Elite. The Elite, for all intents and purposes, would change everything.

Built from 1957-1963, the first-generation Type 14 Elite was nothing short of a miracle of technology and mechanical simplicity, it was also a beautifully resolved shape, with elegant proportions, exceptional visibility, and compact dimensions. At the debut of the Elite in 1957, wandering visitors of the London Motor Car show, at Earls Court, might surely have seen the Jaguar XK150, revising the earlier but dated 120. No two cars could have been seen as so widely contrasting than the lithe Elite juxtaposed against the aging Jaguar, still the leading British heir to the automotive sporting future.

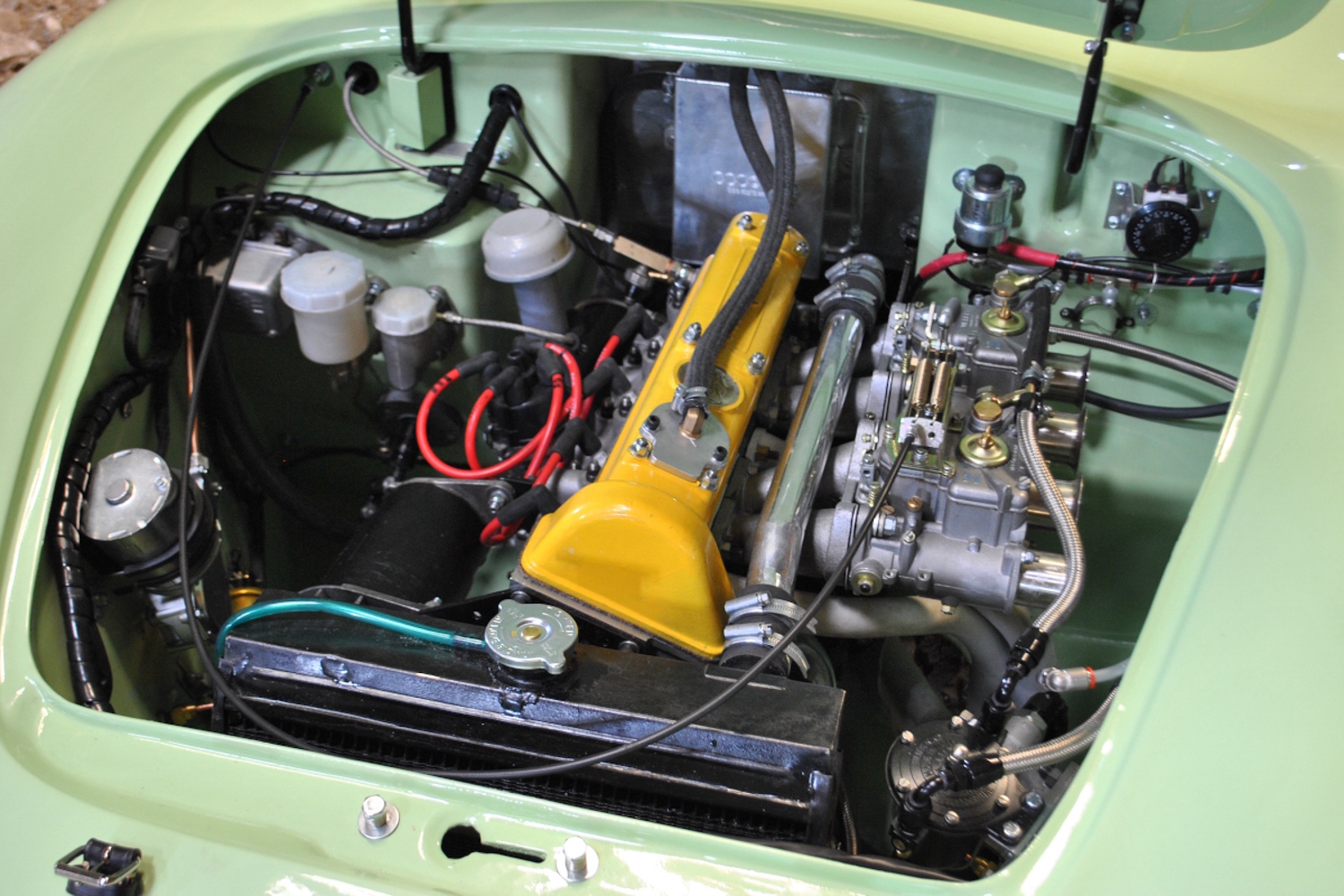

And while the Elite’s exterior design featured dramatic low fenders, wire wheels, and a tight cockpit, the fiberglass monocoque chassis and body, rack and pinion steering, disc brakes all round (rear inboard), and sophisticated suspension design, combined to make a marvelous performance car. Let’s step back a moment to review that list again, each of which are important features in any car, but here with the Elite, a single car contained them all. The heart of the Elite was the unique fiberglass monocoque structure. Unlike early fiberglass cars that were body skins mounted on stiff ladder-type frames, Lotus lifted budding racing technology and weight-saving airframe construction to yield a rigid body and chassis unit that utilized bonded segments for engine and suspension mounting, as well as an integrated cowl hoop that supported door hinges.

Weighing in at 1,300 pounds, but offering exceptional torsional rigidity, the attractive and aerodynamically fluid design not only proved to be highly successful in competition, it proved to be a handsome low-cost alternative to higher priced sports cars with far more complex and often cumbersome or fussy mechanicals. Naturally, all this experimental technology had its drawbacks. The first series of cars were plagued with construction issues from laminating problems, fastening and bonding process flaws to interior vibrations that could shake kidney stones loose. But nothing could vibrate above the impact the Elite received from the excited public. Eventually, Lotus shifted their body production to the Bristol Aeroplane Company where improvements were soon noted, as increased sales followed.

In addition to the weight savings, the aerodynamics were among the best seen in any production car. Achieving a coefficient of drag consistent with cars constructed 40 years later, the Elite was largely designed using intuitive understanding of airflow. Much of the original design is attributed to Peter Kirwin-Taylor, a champion downhill ski racer, accountant and motorsports enthusiast. Kerwin-Taylor conceived of the design originally as a racecar, but something that could also be thought of as a gentleman’s racer.

As the project progressed, Frank Costin and Ford designer Ron Hickman stepped in to finalize the production aesthetics. It would come as no surprise that these extraordinary cars would achieve a remarkable six Le Mans class wins during production. Just over 1000 examples were built, which by today’s standards seems slim, but given the enormous risks Lotus took to fuse such a car together, this number brings far more context to the achievement, both as a statement of their fortitude and ability to complete such a challenging undertaking.

Looking at the Lotus Elite today, it’s easy to see how this car became such an icon of design. The traits that would become so much a part of sports car design through the 1960s, here on the Elite exist in fine form four years earlier. There is no mistaking the imprint that this car had on the evolution of the Jaguar XKE, whose predecessor, the D-Type was more of a wildly undulating-fender 1950s design. Delivered first on the Elite, the long hood, under bumper grille intake, gently rounded chrome front bumper corners, dramatic windshield rake, and lower rear wheel opening all appear on the XKE when it debuted in 1961. What the Elite accomplished as a total design concept was both heroic and daring, yet nothing about the design is out of place, alarming, or disconnected from any aspect of the total form. Each of the gentle curves and modest transitions all happen at a pace that the eye can absorb and understand without landing on a harsh visual stopping point.

Effectively, when viewing the Lotus Elite, your eye begins a visual mapping of the profile and contours, “race-tracking” the perimeter of the form with increasing speed and adoration. With no place to stop, the eyes simply cannot remove themselves from the form. Even the tall cockpit seems to emerge harmoniously from the main form as though nature grew it in place. Not only is the Elite one of those cars that appears perfectly at home in any color, clever two-tone separations of the top and bottom portions of the car still deliver a harmonious whole. Among other notable attributes, the doors are quite large, cutting into the front fenders, but still feeling very much at home in the overall form, there are no scoops, decorative trim, or fussy chrome excesses that plagued so many cars of the late ’50s. Only the tightly bobbed rear end suffers just one design indignity, quad taillights, which replaced the earlier upright rectangular units.

Pure in form and delivered with conceptual excellence the Lotus Elite was both a technical marvel and design darling years ahead of the times. Dramatically sculpted yet beautifully refined, the Elite remains today an understated highlight of sports car design and engineering, setting the standard for literally all sports cars of the 1960s while inspiring contemporary car designers seeking that perfect union of innovative engineering and dynamic visual presence.