How would you, as a recent college graduate, like to have a job that allowed you to drive a very limited production vehicle around the United States and Canada displaying the products your employer makes? Today, you could do that in the Oscar Mayer Wienermobile, but, in 1934, six young engineering graduates did it in McQuay-Norris Streamliners.

McQuay-Norris Manufacturing Company

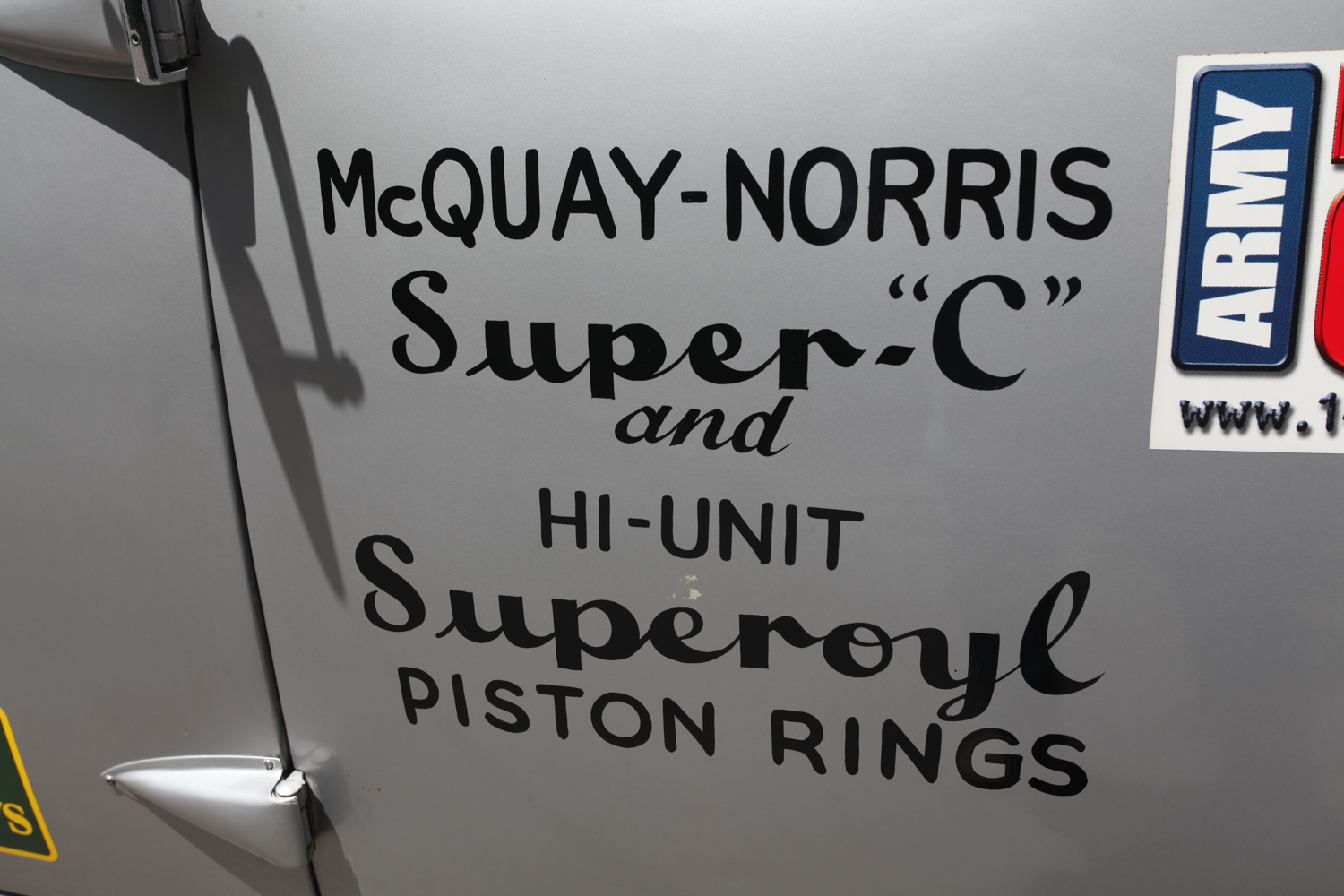

The McQuay-Norris Manufacturing Company began making engine and chassis components in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1910. They made engine parts including pistons, piston rings, bearings, valves, cylinder sleeves, and water pumps, and chassis components including steering knuckles, chassis bolts, bushings and shackles, all for then-current American automobiles. The company subsequently underwent a number of mergers and buy-ins until they became a part of the Affinia Group of auto parts companies in 2009.

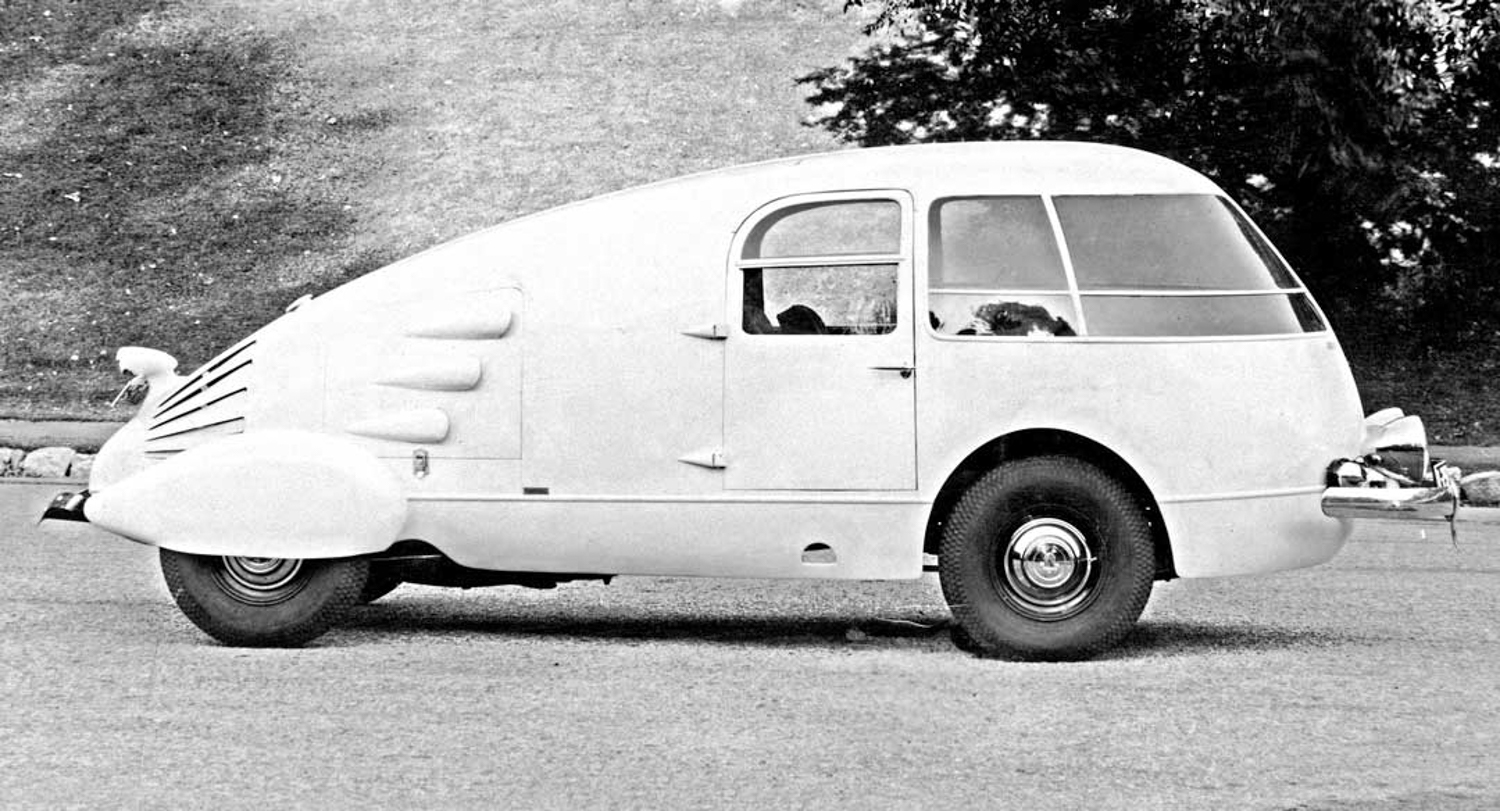

McQuay-Norris Streamliner

Every manufacturing company needs to find ways to promote their products. Someone at McQuay-Norris came up with a very novel approach. The decision was to build six streamlined automobiles on standard automobile chassis and hire recent engineering graduates to visit auto shops and parts houses, show examples of the company’s products, and encourage the shop to purchase from McQuay-Norris. The engineers were also tasked to rebuild the engines so they could testify to the quality of the parts they put in the engine. According to a company brochure, titled “An Explanation of the McQuay-Norris Test Car,” they claimed that: “This car is used solely for testing purposes and is not an advertising car. . . . [And that] this pamphlet is not issued for the purpose of extolling the merits of McQuay-Norris parts but rather to explain the car to interested observers.” It must have been just a coincidence that the “interested observers” were most often owners and mechanics at automobile dealerships, garages, and parts houses.

Although McQuay-Norris claims that “different chassis are used in each of the cars,” an interview with one of their early engineers suggests that they were all the same. George E. Leutwiler was one of those early engineers. He was interviewed by Robert J. Gottlieb in the December 1972-January 1973 issue of Special Interest Autos. Reflecting on his experiences in one of the streamliners in 1934-1935, Leutwiler said, “These cars were all built on standard Ford passenger-car chassis and used stock Ford V-8s up front. The frame wasn’t altered or cut, so I sat exactly where the driver sits in a 1932 or 1934 Ford, about halfway back in the car. There was a lot of glass area (actually Plexiglas) all around, but these cars had no windshield wipers, so if you got caught in a rainstorm, and you drove fast enough, the raindrops took care of themselves, because the water flowed up and over the top of the car.” The windshield extended to the front of the car, where the radiator would have been on a conventional Ford sedan. Leutwiler continued his reminiscences, “There was no rear window. We used rearview mirrors on the outside. These cars were easy to drive, but they had some peculiarities. For instance, you needed good shocks or the car would dance around a lot because of the donut tires.” His comment about the tires is likely because the cars used General Jumbo Airwheels and tires, the first balloon tires of the 1930s.

Apparently, just showing up in one of these cars made access to those who might purchase McQuay-Norris parts simple. Leutwiler remembers: “I made a lot of calls – maybe 18, 20, or as high as 36 calls a day on different independent repairmen and dealers, I’d just drive up to a place, park and wait for the crowd to gather. It was a remarkable seller. We’d hold what you’d now call seminars – get-togethers with mechanics, jobbers, wholesalers, distributors – and show them our instruments inside the cars, explain some of the reasons for them, and then extol the virtues of McQuay-Norris parts.” During the winter months, the cars stayed mostly in the south, but when the weather was good, the engineers took them all over the U.S. and Canada looking for potential users of McQuay-Norris parts.

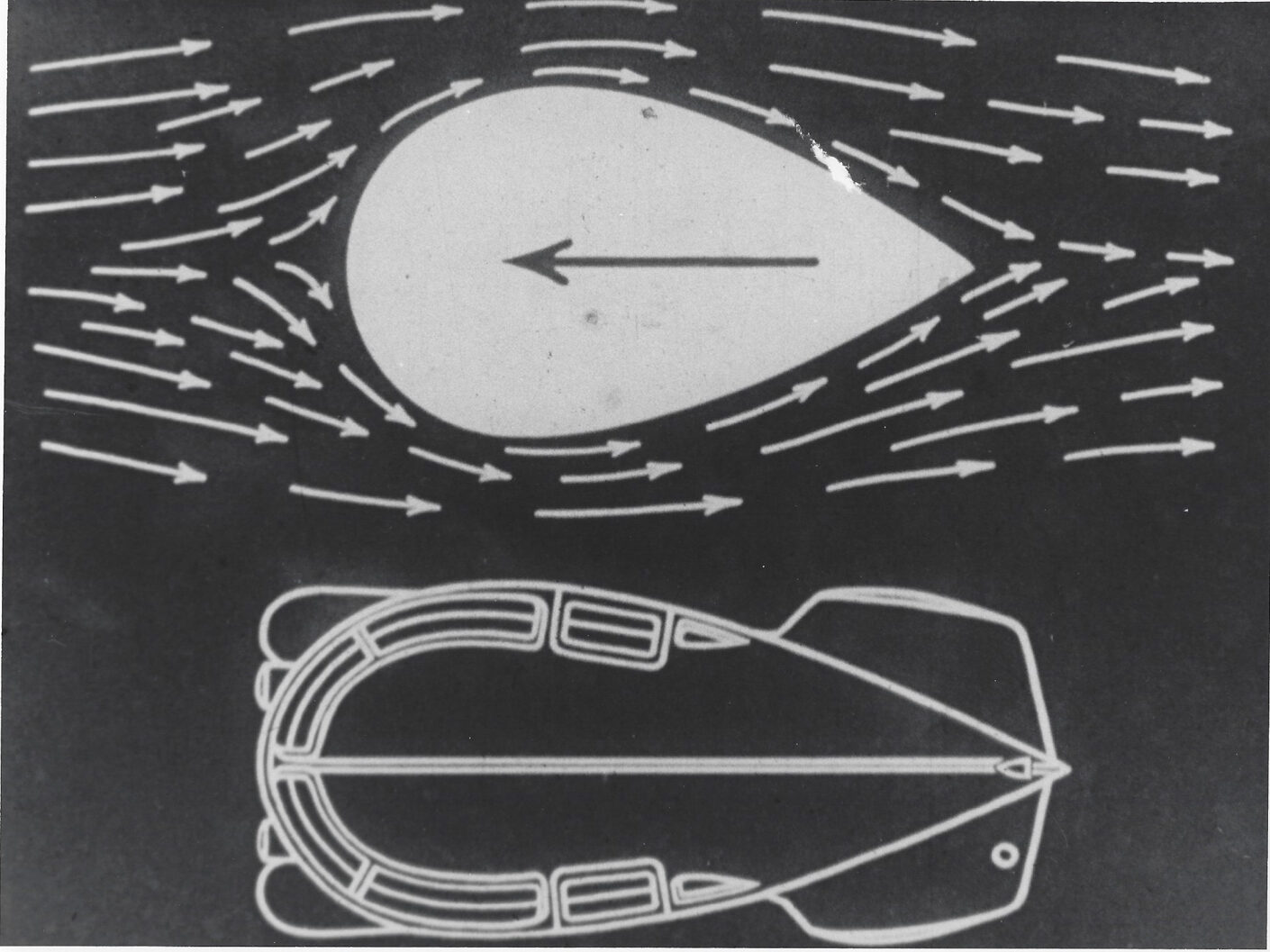

The company called the car a “Tear Drop” because it was designed to approximate the shape of a drop of water falling through air, claiming that the tear drop shape was the most effective in reducing wind resistance. A company brochure titled “Proving It,” said, “The purpose of the Tear Drop Fleet is to test motor performance on the road.” Each car was equipped with a full slate of instruments – “gas analyzers, viscosimeters, oil temperature gauges, blow-by meters, and other scientific apparatus.” Those other apparatus included a clock, speedometer, ammeter, gas gauge, oil pressure gauge, water temperature gauge, oil level, exhaust gas temperature gauge, compression gauge, and vacuum gauge. The brochure also claimed that there were three advantages in using a tear drop test car over a conventional automobile:

- “It reduces the load on the engine at high speeds.”

- “It places the driver in intimate sound relation with the engine at all times. The engine is really riding right inside with the driver.”

- “It makes available a large compartment for instruments.”

The company downplayed the idea that the shape of the car would allow it to go faster than a conventional automobile, and their engineer/drivers were instructed to make no claims about speeds. The company brochure did say that “this Tear Drop body mounted on a conventional chassis will increase the speed of the car some 10 to 15 miles an hour. Any increase in speed is due to a reduction in wind resistance.” Leutwiler remembered driving “over 100” occasionally.

The cars had seats only for the driver and a passenger and used the standard seats from the Ford V-8. Leutwiler said, “There was no backseat, but there was room for the blowby meter and one suitcase behind the driver.” In “Proving It,” the company went in to detail about the importance of this one instrument. “The Blow-By Meter is the most important instrument in the car. It measures accurately any gases that leak past the pistons into the crankcase. It shows the rate of blow-by as well as the accumulated cubic feet of blow-by. Blow-By is important because too much overheats the piston assembly and produces a sludge in the oil. Blow-By accounts for poor fuel economy and increases the temperature of the water in the cooling system. Blow-By produces an unhealthy atmosphere in a closed car, frequently resulting in headaches and nausea, sometimes with fatal results.”

The one gauge missing from our profile car was the Blow-By Meter, but, according to Jeff Lane, founder of the Lane Motor Museum in Nashville, Tennessee, (https://www.lanemotormuseum.org/), there are suspicions that the gauge never really produced useful information. The Lane Museum McQuay-Norris Streamliner is the only one known to still exist.

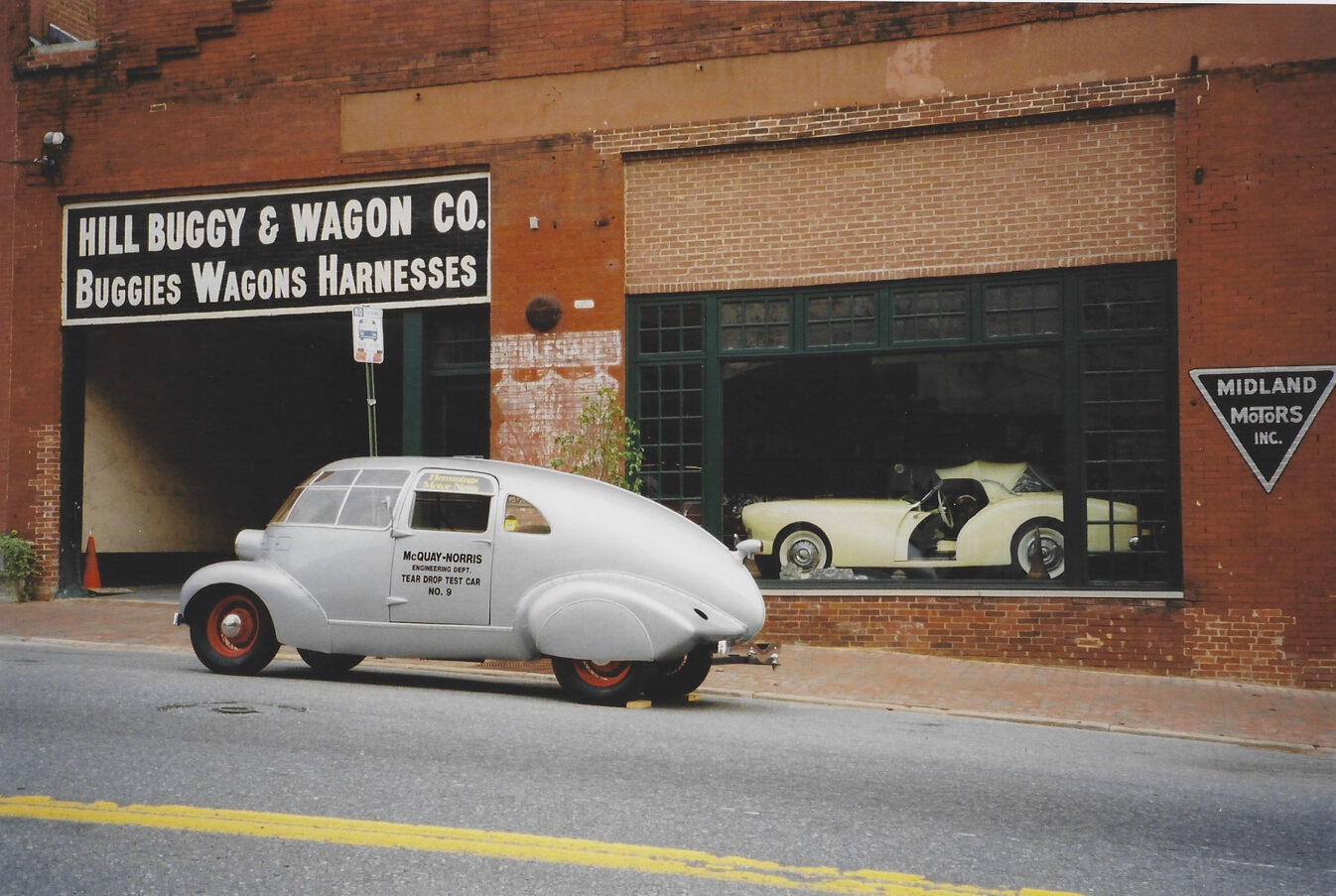

The bodies of the streamliners were sheet steel, although the doors were skinned in aluminum. Body framing was all wood, as was common practice at the time. They were built by the Hill Auto Body Metal Company in Cincinnati, Ohio, and were reminiscent of a rear-engined tear drop car called the Arrow Plane built for Lyman Voelpel.

The Hill Company had experience in building aircraft wheel spats for trucks, including the occasional racecar or streamliner. John A. Hill worked with the McQuay-Norris chief engineer, Arden Mummers, to develop the shape for the new cars. Construction began on the cars in 1932, and it appears that one was completed in 1933 with the remaining five constructed in 1934.

Engineering Dept Test Car No. 9

The streamliners were used for six years between 1934 and 1940. Leutwiler remembers that the cars were individually sold by McQuay-Norris, most becoming delivery trucks, although one was used on top of a sign at a shop. As of 1973, it was believed that none still existed, but there was one. Thanks to that 1973 Special Interest Autos article, a young attorney, Michael Shoen, was intrigued and began a search for any of the remaining streamliners. His search and discovery of the last of them was detailed in Special Interest Autos in their September/October 1998 issue.

Shoen was incredibly persistent in his search for a McQuay-Norris Streamliner. Along the way, he found and bought the Arrow Plane but soon sold it. Built on a Ford Model A chassis turned backwards under the streamlined body, it was undriveable, so he resumed his search for his original target. Michael Lamm reported in the article, “By 1975, after a lot of phone calls, letters and sheer persistence, Shoen managed to track one McQuay-Norris car to a shop in Columbus, Ohio. He found it in very sad condition. It had stood outside for some 20 years, and the wooden body framing was severely dry-rotted. The metal panels had collapsed and were literally down on the chassis frame, with the fenders wedged against the tires.” The owner of the Ohio shop had found the car in 1973, and, as a restorer of Morgan sports cars, thought he could build new body framing for the streamliner. When the owner finally accepted that he didn’t have time for the project, he sold the car to Shoen. As the owner of two vintage gliders, Shoen was familiar with Elwood Pullen in Elmira, New York. Pullen was retired from the aircraft industry where he had been the foreman of the Schweitzer Aircraft prototype and fabrication shops. As an expert in woodworking and Plexiglas, he began restoring wooden airplanes in his retirement.

Lamm detailed the restoration: “Pullen removed the streamliner body from the Ford chassis and then carefully took out the wooden structural members and used most of them as patterns to make new ones. A few were too fragile, so he designed and built substitutes. Pullen took out all the running gear and supported the metal body in place over the frame by suspending it from special scaffolding. This allowed him to fit each new wooden member in place as he finished it.” While the steel body was in reasonably good shape, all the Plexiglas was broken. Pullen used the framing as the pattern for new Plexiglas. Door panels, windows, and much of the trim had to be remade. Pullen put the car together, painted it in primer, then sadly passed away.

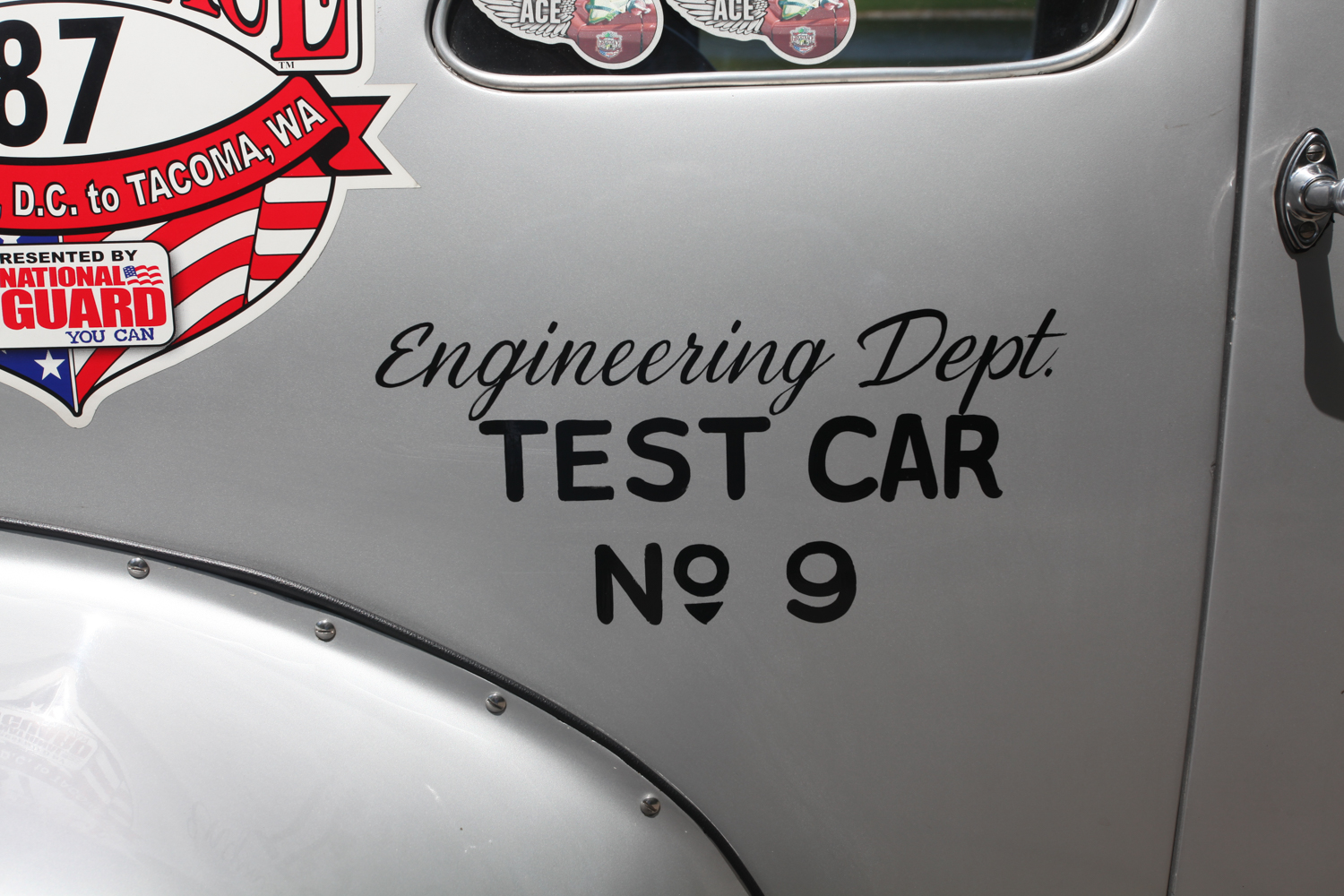

With Pullen’s death, Shoen took possession of the car in 1982, and looked for someone to complete the restoration, especially someone to rebuild the instruments. Three instruments were missing, and one, the important blow-by meter, has never been found. Shoen had the restoration completed, albeit without the three instruments, to make the car as originally correct as possible. By 1990, the car was driveable, but Shoen had accumulated quite a collection of cars, motorcycles, and airplanes and decided to sell off most of his collection, including the McQuay-Norris Streamliner. Oddly, while only six of the streamliners were built, this car has always had the following on its rear quarter panels – “Engineering Dept Test Car No.9.”

Where the Streamliner went next is a bit fuzzy, but eventually it was acquired by Hyman, Ltd., an antique and collector car dealer in Maryland Heights, Missouri. The car was offered at auction at Amelia Island but did not sell. Jeff Lane saw the car, then, “we talked about a price, and we bought it from Hyman.” The only part missing on the car was the blow-by meter, and Lane has thought about it: “Was it something they made up? Is it a real gauge? I’m thinking that part of that might be marketing folklore, but not real.”

As with nearly all the cars in the Lane Motor Museum, the McQuay-Norris Streamliner is driveable, and it gets driven. Lane tells a story from when he took it on the 2005 Great Race from Washington, DC, to Tacoma, Washington: “It was a great car for the Great Race because, although the engine is in front of you, you’re sitting in the shade. No matter how the sun beats on you, you’re sitting in the shade. It’s got these vents in the front that open and provide outside air to you. The most exciting story was that the fuel pump went out in the middle of nowhere. We stopped at a farm. I walked over and knocked on the door. A lady answered and I asked if she had any gas and a gas can she could lend us. She said Walmart fixed her bike that day, so she was in a good mood and gave us a 2-gallon gas can. I poked a hole in the bottom, put it on the shelf and had it gravity feed into the carburetor. We were on a timed leg, so if you were more than a half hour late, you were penalized pretty severely. My thing was not to be more than a half hour late, but you don’t know where the end is. Turns out we had another 30 miles to go, and we barely made it before we ran out of gas. We were able to change the fuel pump. It was pretty exciting driving along with a 2-gallon tank sitting on the dash and not knowing where the end of the leg was. If it had been 60 miles, we were in the middle of nowhere – it would have been a disaster.”

Driving Impressions

Thank you, Jeff Lane, for having driveable cars in your museum and for allowing Vintage Road & Racecar to profile them. It is enjoyable to tell the stories of unusual automobiles, and the McQuay-Norris Streamliner has been on the magazine’s bucket list for several years. Vaccinations for Covid-19 and a lessening of the pandemic allowed the author and a friend and fellow Alfista, Bruce Tilden, to hustle over to Nashville to spend some time with Lane, Robert Jones, the museum curator, and the McQuay-Norris Streamliner. After interviewing Lane, and going through the museum’s file on the car, Tilden and I took the Streamliner to do some photography at a park recommended by Lane. We were surprised that the directions took us nearly into downtown Nashville to get there, so it was a very interesting drive in an 87-year old car!

You can not drive a car like this in traffic without attracting attention. There were those who decided to ignore the Streamliner, there were others who gawked and pointed, and there was even a homeless fellow who stopped waving his sign to ask what kind of car it was. The real adventure, though, began when I turned off the busy streets onto a more residential one that led down some steep hills to the park. Lane had warned that the brakes were a bit weak.

Heading down the tree-lined hill, it was belatedly apparent that I was approaching a four-way stop intersection with the stop sign mostly obscured by vegetation. Oh, those brakes! As the car responded to my hard push on the brakes, my adrenalin peaked as the car swerved and bucked as it slid into the intersection. Thankfully, the person stopped at the cross street saw the Streamliner coming and decided to wait to see how this was going to turn out before entering the intersection!

What can I say about the handling of the Streamliner? Well, it’s a 1934 Ford, so it handles like a 1934 Ford. There were two hairpin turns into the park, and it took them, slowly, in its stride. Acceleration was a bit of a surprise, as it was quite spritely, especially for a 1934 automobile. Despite Lane’s comment about always being in the shade while driving the car, it does take some effort to drive in traffic, so I was a bit sweaty when we got the car back to the museum. I suspect that the car is a pleasant driver on the open road. On city streets, it was a bit of a handful, although the attention it caused kept me smiling.

Specifications

| Body | Streamlined steel over wood framing |

| Chassis | 1934 Ford |

| Frame | Box type with center cross member and X-member |

| Wheelbase | 112 inches |

| Length | 173 inches |

| Height | 68.5 inches |

| Width | 72.5 inches |

| Front track | 55.5 inches |

| Rear track | 56.75 inches |

| Engine | Ford 90˚ V-8, L-Head, cast iron block |

| Displacement | 221.0 cid |

| Bore/Stroke | 3.0625/3.750 inches |

| Power | 85 bhp @ 3800 rpm |

| Torque | 150 ft-lbs @ 2200 rpm |

| Transmission | 3-speed manual |

| Steering | 3-tooth worm and sector |

| Brakes | Internal expanding mechanical drums |

| Suspension | Transverse springs front and rear |

| Wheels | 17” welded drop center rims |

| Tires | 5.50/17 bias ply |