An amazing thing happened in Chattanooga, Tennessee, in the fall of 2019. A couple of automobile enthusiasts proposed the Chattanooga Motorcar Festival and convinced the city to allow it to happen. There was a time trial, rally, and concours. It was to be an annual event, but Covid-19 interfered and it was postponed in 2020. The second Chattanooga Motorcar Festival happened in October 2021, and it was even more successful than the first one. The last day of the three-day event was a concours d’elegance held on the streets of Chattanooga’s West Village. There were some spectacular automobiles on display, but one somewhat unspectacular car caused the people who read the history of the car to take a second, closer look. The car, a 1928 Buick Country Club Coupe, had been purchased new by Barney Oldfield, the “Speed King of the World,” for his former wife, Bess, who had been his second wife and would become his fourth in 1945. Sometimes an unremarkable automobile can be pretty remarkable when its story is known.

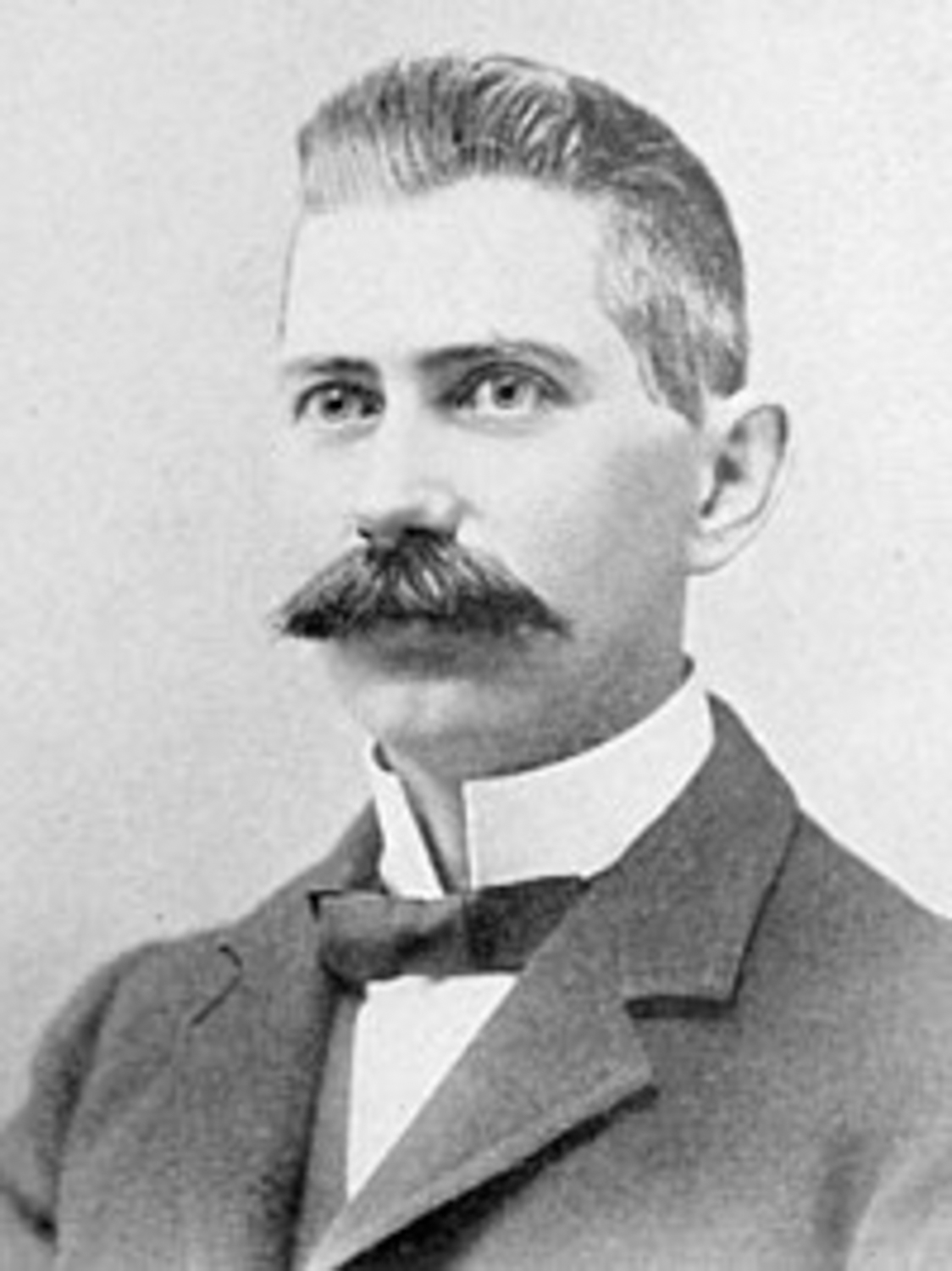

Donald Dunbar Buick

David Dunbar Buick may be the most forgotten man in the history of the automobile. A contemporary of Buick’s is reported to have said, “Fame beckoned to David Buick – he sipped from the cup of greatness . . . then he spilled what it held.” In his book, “Seventy Years of Buick,” George Dammann wrote that Buick “was an inventor of far above average talent, but as a businessman he was a complete flop.” The reality about David Buick appears to be that he just didn’t care about fame; he just liked to tinker.

Buick was born in Abroath, Scotland, in 1854 and was brought to Detroit when he was two. As a young man, he worked for the Alexander Manufacturing Company making plumbing fixtures. When the company failed, he and William Sherwood formed Buick and Sherwood to continue the business. Buick was an inventor, and he created and patented the process for applying porcelain to cast-iron baths and sinks. Buick lost interest in tubs and potties when he saw early internal combustion engines, and he started to tinker with them. In 1901, he sold his part of the plumbing business and invested in the Buick Auto-Vim and Power Company, where he made marine and farm engines. Buick designed and produced one automobile during this time, with the help of Walter Marr. It may have been sold to Marr, at least it seems that Marr offered $300 for the car. Buick and Marr both had short tempers, resulting in Marr’s departure from the company.

Buick Auto-Vim and Power Company failed because of erratic production and failure to deliver on orders, a problem that would recur with the Buick Manufacturing Company, which was his next endeavor. In order to save the company, brothers Benjamin and Frank Briscoe stepped in and the Buick Motor Company was created in 1902. One of the innovations Buick included in the design of his new car was the valve-in-head engine. The Briscoes had supported Buick with funds and materials – their business was sheet metal manufacturing. As partial repayment, Buick promised the car that was in the process of being built to them if they provided $650 to complete it. Apparently, it cost the Briscoes about twice that amount to complete the car, which was finally ready in 1903. On May 19, 1903, the brothers incorporated the company with capital stock of $100,000, of which the brothers held $99,700 and Buick held $300. Buick could purchase the Briscoes’ stock for the $3500 then owed them, but he failed to do so, and the brothers took over management of the company. The brothers, faced with continued production problems, sold controlling interest in the company to James H. Whiting, owner of the Flint Wagon Works, who moved the company to Flint, Michigan.

Marr returned to the new company where his focus was on the valve-in-head engine. While Whiting intended to just build engines, Marr and Buick had other ideas. With Marr working on the engine, Buick focused on the chassis and body construction of a new car. A prototype was completed in the summer of 1904 and was taken on a successful test run by Marr and Buick’s son. The result of the test run was 17 orders for the new car, known as the Model B. It was rugged and reliable with a sturdy chassis, two uncomfortable seats, and Marr’s two-cylinder engine that he said could “develop 19 to 21 horsepower in a pinch.” The first production car was delivered in August 1904. Total production in 1904 was less than 37 cars, the $37,500 set aside for development was gone, and creditors were unhappy. Whiting was desperate for a solution to the company’s problems. The solution turned out to be William Crapo Durant, who bought the company in 1904. On November 1, 1904, with Durant at the head, the company’s future changed dramatically.

Durant didn’t just jump on the opportunity to purchase Buick, he was cautious and saw Buick as a challenge. Before he bought the company, he put the car through a lot of tests and discussed both Buick and the future of the automobile. He bought the company when he became convinced that the automobile was the future. Unlike David Buick, Durant was a promoter. Durant increased the capital from $75,000 to $800,000. In one day, he sold $500,000 in stock to Flint residents. A year after Durant took over, the company had stock equal to $1,500,000. Durant attended the New York auto show in January 1905 and took 1,108 orders. He put Buicks in Durant-Dort carriage agencies all over the United States, making Buicks the most displayed automobile of its time. On a train layover in Detroit, he visited the Buick agency, contacted potential buyers, and sold three cars before he had to be back on the train.

David Buick seemed not to care what was happening to the company as long as he was able to continue his tinkering, but his tinkering was costing the company production delays. Durant had little tolerance for Buick’s interference and moved him out of the engineering department. It wasn’t long before Buick became unhappy with his status in the company. He finally left in 1908 with $100,000 that Durant gave him as an encouragement to find other opportunities. Buick was never to succeed in business. He tried oil speculation, was involved with the Lorraine and Dunbar automobile companies, and even sold real estate, but failed in all of them. He eventually returned to Detroit where he worked as a receptionist and instructor at the Detroit School of Trades. He died penniless on March 5, 1929.

Buick Motor Company

Prior to Durant’s takeover, the company had been producing the Model B four-seat tourers that had as much as 22 horsepower in the more expensive versions. The Model C was developed for 1905, but it was only able to be put in production because of Durant’s input of cash. Thanks to Durant’s money, 750 cars were sold that year. The Model D was even better, with shaft drive and a three-speed sliding gear transmission. Buick, the company, blossomed. In its advertising, the company said, “We build nothing but high grade automobiles, and when better automobiles are made, Buick will build them.” The number of cars sold in 1907 was 4,641, second only to Ford. That year, a four-cylinder, front-engine car was introduced as both a roadster and a touring car. It had a 4180-cc engine with side valves in a T-head. It would be the only non-OHV engine Buick would ever produce. The Model 10, in 1908, returned Buick to overhead valves in its 2702-cc four-cylinder engine with epicyclic transmission – high gear was engaged by a lever on the right side; low gear was operated via a pedal. The Model 10 had style, performance, and reliability. The next year, Buick increased from one model to four and produced 14,606 cars. Durant also took the company racing. A Model F was driven from New York to San Francisco in 24 days 8 hours and 45 minutes, beating the previous record by nine days. In 1909, Buick won 166 (90%) of the events it entered. The Model 10 was even marketed for “men with real red blood who don’t like to eat dust.”

Durant, though, had aspirations beyond Buick and began pursuing them in September 1908 when he incorporated the General Motors Company in New Jersey with an initial capitalization of $2000. Then Durant’s GM bought Durant’s Buick that same month. A month later, he bought Olds Motor Works. He wanted to bring the production of parts into the company, so he bought many of the companies that supplied GM. And he bought Oakland, which became Pontiac, and Cadillac. He even tried to buy Ford for $8 million, and Henry Ford agreed as long as Durant could pay with cash. The agreement died. The buying spree put the company in financial trouble. There were reports of Durant having to borrow money to pay wages. It became a crisis that was only resolved when two banks, in November 1910, agreed to give the company a $15 million loan, of which they kept a $2,500,000 commission, contingent on Durant leaving the company. The company was saved, and Durant was out.

Buick produced around 13,000 cars in 1911, only one of which was still a two-cylinder with chain drive. The company now had the largest automobile factory in the world and was producing almost all of its parts. There were leadership changes in subsequent years – Charles W. Nash, who Durant had gotten appointed as President of Buick became President of GM in 1912 and was succeeded at Buick by Walter P. Chrysler who brought a new cost consciousness to Buick. At the same time, Durant was working to reverse his banishment from the General Motors he had created. During 1911, Durant organized three small automobile companies, one of them being Chevrolet. He then consolidated the three companies into Chevrolet, making it very successful. Two years later, Durant quietly began trading five shares of Chevrolet stock for one share of General Motors stock and was very successful. On September 16, 1915, Durant retook control of GM – Chevrolet had bought General Motors! Many, including Nash, resigned, but Durant offered Chrysler $500,000/year in stock if he would stay for three years. Durant transformed the holding company, General Motors, into an operating company, General Motors Corporation, in 1916. Durant was again buying up companies to enlarge GM even further, and it went well until the post-WWI recession, when he continued to push production, causing inventories to rise and stock prices to fall. General Motors was $30 million in debt. A DuPont-Morgan syndicate assumed the debt in exchange for $2,500,000 in stock and Dupont’s resignation – he was out again. Pierre DuPont became President of GM. Alfred P. Sloan, Jr. managed the reorganization of the company and became its president when DuPont retired in 1923.

In the background of all this managerial chaos, Buick continued to build cars. By 1912, production was up to around 20,000 cars. Chrysler’s first full year at Buick saw his approach to cost containment – the 1913 models were simply facelifted versions of the previous year, although with electric lights and starter. They also got confusing model names. The previous Models 24 and 25 became Models 34, 35, and 36, while Models 30 and 32 became Models 28 and 29. Beverly Rae Kimes commented on Chrysler’s management of Buick in her article titled “Wouldn’t You Really Rather Be a Buick” in Automobile Quarterly (Volume VII/No.1): “For all the efficiency and logic Walter Chrysler brought to Buick production management, he could not somehow do the same for Buick Model designations.” That year, Buick was third in the nation behind Willys-Overland and, the leader, Ford.

Buick celebrated its 25th anniversary in 1928 with a Silver Jubilee model that included hydraulic shock absorbers. The subject of this profile is one of those cars, a Standard Six Country Club Coupe, so the somewhat detailed history of Buick will end with that year. What happened at Buick after 1928 included the Great Depression, WWII, a lot of chrome in the ’50s, a return to racing, a few interesting muscle cars, and survival during GM’s drawdown of makes because Buick had developed quite a market in China.

Berna Eli Oldfield

Berna Eli Oldfield was born in Fulton County, Ohio, on January 29, 1878. He was named after his father’s fellow Civil War soldier, Berna Showmaker, and his mother’s father, Eli Yarnell. In 1893, he dropped out of school to work with his father in the kitchen of a mental institution, but soon left that to become a bellhop at the Broody House in Toledo, Ohio. Oldfield had a very outgoing nature, and working at the hotel taught him how to get along with people. It was there that he was given the nickname “Barney,” and, although he didn’t care for it at first, it stuck, and he accepted it. This was during a period when bicycles were becoming extremely popular with Americans, and Oldfield was no exception. A hotel guest had a lightweight bicycle, and Oldfield would “borrow” it when the guest retired, and taught himself how to ride . . . fast. He always had the bike back before the owner woke. Riding that bike started Oldfield thinking that he could be a successful bicycle racer, so he entered his first race May 1894. On a borrowed Royal Flush bicycle, Oldfield raced in a field of 17 racers on an 18-mile cross-country course. His inexperience caused him to fall back, but he observed the more experienced racers and learned their tricks. He finished second! Bicycle racing was good to Oldfield. His successes got him a job as a salesman for the Stearns Bicycle Company, then as one of their racers. He was an aggressive and very successful competitor. Aggressiveness proved to be a trait that lasted through his racing career.

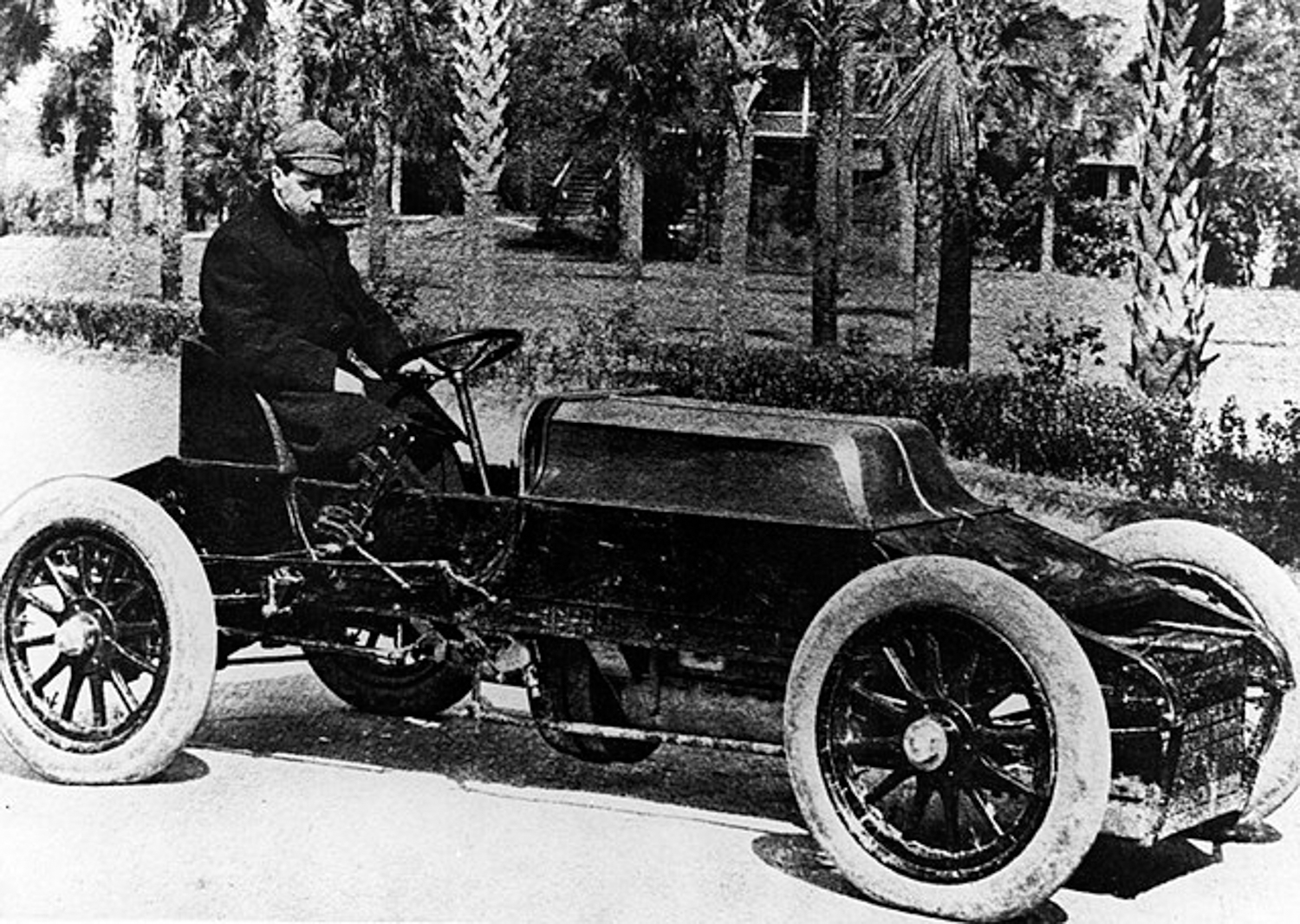

Tom Cooper, another bicycle racer and friend of Oldfield’s, bought a tandem bicycle powered by a gasoline engine. Oldfield had little interest in internal combustion engines, but Cooper convinced him to join in an effort to make money by setting speed records. Their first attempt was not as successful as they had hoped, because it was overshadowed by a fellow named Henry Ford beating another guy named Alexander Winton in crude automobiles of their own design. Eventually, Cooper was disillusioned enough to quite racing and to buy a coal mine in Colorado with Oldfield as his partner. The mine was a failure, and Cooper returned to Detroit to join with Ford. Oldfield took the motor tandem and a racing bicycle to Salt Lake City and set speed records. Cooper, when he saw what Ford had planned, wrote Oldfield and encouraged him to come to Detroit and join with Ford as a mechanic. Cooper also hinted that Oldfield might be able to drive one of the two racecars being built. The cars were little more than a frame with an engine in order to save weight. And it was quite an engine that was being constructed. Bore and stroke were each seven inches, giving each of the four cylinders a displacement of nearly 1080 cubic inches.

The first test of the car, at a horse track in Grosse Point, was a failure. Ford, concerned that any failure of his car in a race would affect his attempts to create his own automobile company, sold the cars to Cooper. The cars, one red and the other yellow, were taken to Dayton, Ohio, for testing. The yellow car refused to start, and the red one ran poorly. Oldfield cut a hole in the gas tank, inserted a rubber hose, and blew into the hose, becoming the car’s fuel pump. The car ran fine. In his book, “Barney Oldfield – The Life and Times of America’s Legendary Speed King,” William F. Nolan reported that on a test ride, Ed “Spider” Huff, the mechanic, said “She goes like ‘999!” He was referring to a steam locomotive, Number 999, which had set speed records for trains. The car became “999.”

In October 1902, Cooper, Huff, and Oldfield were back at the track in Grosse Point to race against Winton in his “Bullet.” The handling of “999” worried Cooper and Huff, so Oldfield drove the car. In practice, Oldfield was fastest at 1 minute 6 seconds over the mile course, and in the race, Oldfield beat Winton. There were two very positive outcomes from that race – Alexander Malcomson agreed to finance the Ford Motor Company, and Barney Oldfield realized it could be possible to make money with this car. Seven months later, the three partners had “999” at the Empire City Track in Yonkers, New York, to race against a Peerless. Oldfield won, and with part of his cut of the winnings, $650, he paid off the mortgage on his parent’s home. In Indianapolis in June 1903, Cooper and Oldfield raced each other. As an added incentive, and additional $250 was offered to whoever broke the minute mile. Oldfield became the first man to drive a gasoline-powered automobile around a mile track in less than a minute – his time was 59 3/5 seconds. He bettered that time a month later when he drove the mile in 55 4/5 seconds.

Oldfield’s successes boosted his ego, and he showed that he knew how to promote himself. William F. Nolan reported in his book that Oldfield described his sub-minute mile drive with his typical hype:

“You have every sensation of being hurled through space. The machine is throbbing under you with its cylinders beating a drummer’s tattoo, and the air tears past you in a gale. In its maddening dash through the swirling dust the machine takes on the attributes of a sentient thing. . . . I tell you, gentlemen, no man can drive faster and live.”

The hype seems to have worked. Winton soon offered Oldfield $2500 per year plus maintenance and transportation expenses to drive his Bullet No2, a car powered by two, four-cylinder engines belted together. Oldfield was again setting records in Bullet No2, but he occasionally drove a four-cylinder Winton called the “Baby Bullet.” An accident in the “Baby Bullet” killed a spectator and made Oldfield consider quitting, but he ultimately decided to continue. One outcome of the accident was a chipped molar, and that resulted in what has become the classic picture of Oldfield. In order to cushion his teeth while driving on rough dirt tracks, Oldfield began racing with a thick cigar clenched in his teeth.

With success came problems for Oldfield. He grew up poor, struggling to make his way, then racing gave him more money than he could have imagined. He began living beyond his means, spending lavishly, leaving big tips, betting on horses and boxers, and was soon overextended. The American Automobile Association (AAA) was the sanctioning body for “legitimate” automobile racing in the United States. Races not under AAA sanction were consider outlaw races, and AAA drivers were not allowed to participate in them. Short on funds, Oldfield decided to skip an AAA race commitment and instead entered an outlaw race that offered more money. AAA fined him $100 for the infraction, and Winton, upset with the negative publicity, fired Oldfield. Unfortunately, Oldfield’s racing career would be known as much for his battles with AAA, lavish spending, bar fights, and a level of misbehavior as it was for his spectacular feats behind the wheel of an amazing variety of racecars.

Oldfield was not unemployed for long. He was quickly hired by Lou Mooers to drive the Peerless Green Dragon. Driving the Green Dragon and Green Dragon 2 resulted in a lot of success for Oldfield, but also caused some changes in his life. A rock broke Oldfield’s goggles while racing the Green Dragon, resulting in a crash that killed two spectators and put Oldfield in the hospital. While recovering, he received flowers from Bess Holland, a woman he had met at a party. She helped nurse him, and eventually they married – lots more about her later. Oldfield also railed at spectators, saying “They’re like a pack of vultures. They pay to see me drive because they want to be there when something lets go. They want me dead, but I figure to fool ‘em and stick around a while.” Stick around he did, racing Green Dragon 2 to win the American Championship over Earl Kiser in Bullet in October 1904. In 18 weeks, Oldfield raced at 20 tracks and won every race. He now held speed records for 1, 9, 10, 25, and 50 miles.

During 1905, Oldfield, now having hired William Hickman Pickens as his advance agent, made a decision that temporarily would change his approach to his fame. He had a number of serious crashes, including one that destroyed the Dragon, but it was after Earl Kiser and Webb Jay were badly hurt in races that Oldfield decided to go into show business. His opportunity on stage came in a play called “The Vanderbilt Cup” which played at “The Broadway” in New York. Oldfield would race the Green Dragon against Tom Cooper in the Peerless Blue Streak on stage – on a treadmill with moving scenery. He made $2000 per month in the play. When the play went on the road, after ten weeks in New York, Oldfield went along until the San Francisco earthquake made him reconsider his future. He said to Pickens, “I can’t go on living a fake life on stage. I belong back in the real world, and that’s where I’m headed.” By the spring of 1906, Oldfield was racing again.

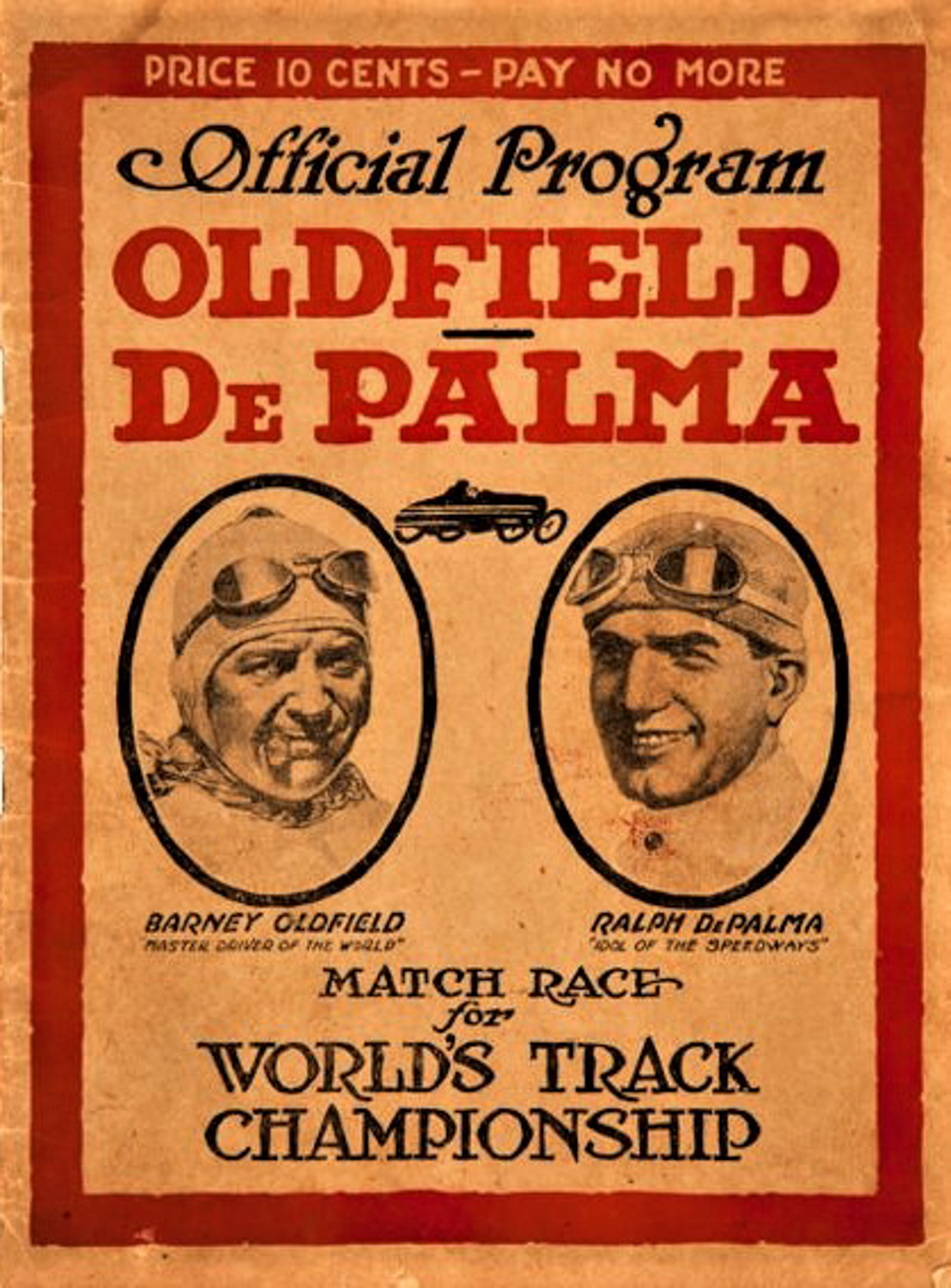

The next few years included a variety of racecars, wins and losses, speed records, incredible bravery, some bad behavior, and more sanctions. Early in 1907, Oldfield learned that he could make $3000 for every appearance, so he bought Green Dragon No3 and the Peerless Blue Streak, and he hauled them from event to event in his own railroad car. The next spring he sold the cars and announced he was retiring, until Harlan Whipple, then president of AAA, offered him a Stearns for the season. He raced the Stearns on tracks and raced trains with it, but positive results were not consistent. At a track in Massachusetts, he was beaten by Ralph De Palma and left the track without congratulating him. De Palma was insulted, and a long feud ensued between the drivers.

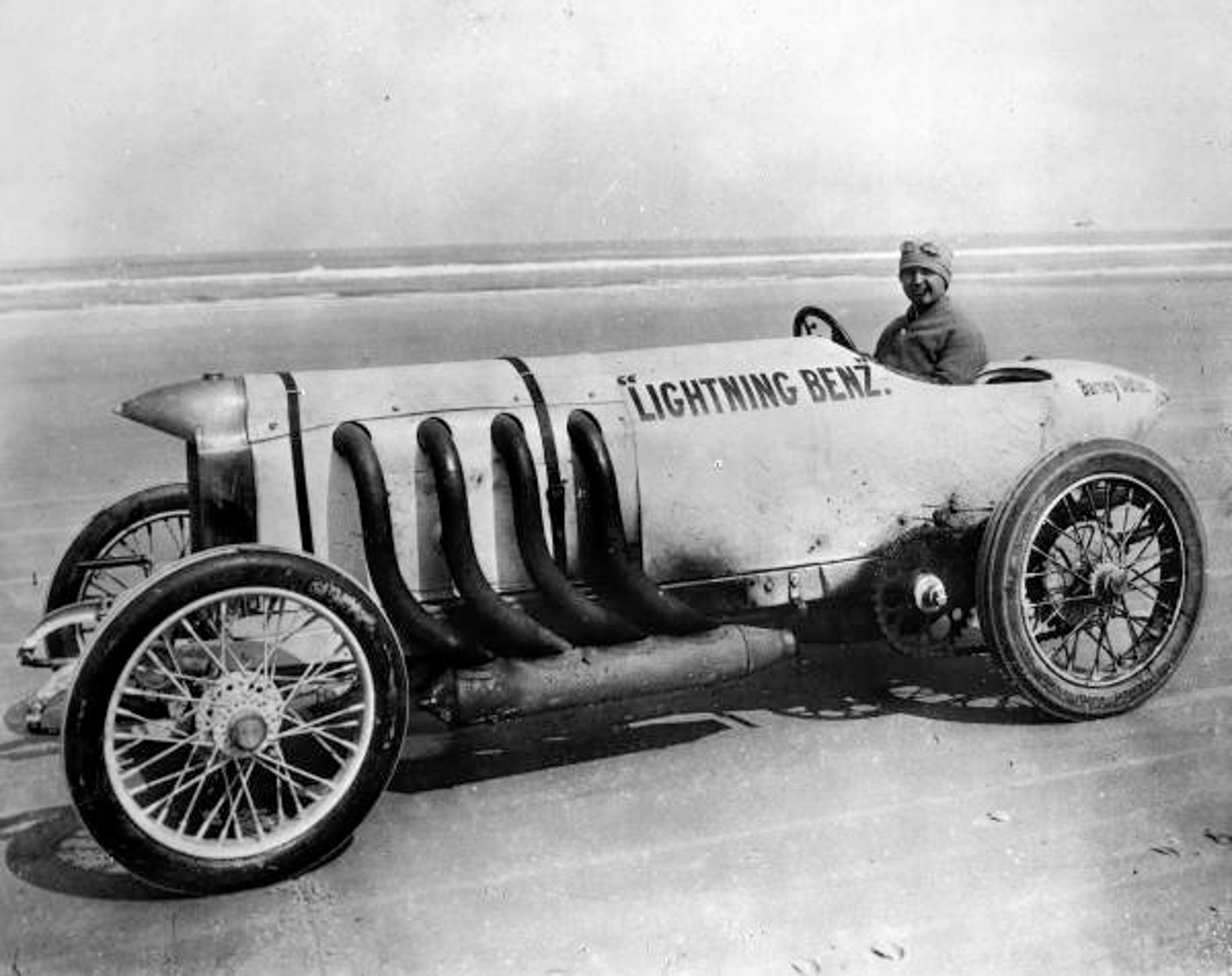

While he was campaigning a National called “Old Glory,” Oldfield decided to pursue speed records again and bought the “Lightning Benz for $4000.” With that car, he set a number of speed records at the new speedway in Indianapolis. He raced the National in the first race at the Speedway, a 300-mile race, in August 1909. With the track surface deteriorating, the race was called after several cars had crashed. Oldfield was running fifth. After running another non-sanctioned event and being punished again by AAA, Oldfield decided to go after the land speed record. To do it, he traded his Benz and $6000 for a real monster of a car, the “Blitzen Benz.”

The Blitzen Benz had a 21.5-liter overhead valve four-cylinder engine with chain drive. On the beach at Daytona, Oldfield ran 131.7 mph on March 16, 1910, setting a new land speed record that was 4.2 mph faster than Fred Marriott had run in his Stanley Steamer in 1906.

Oldfield drove the Blitzen Benz to more records and race wins, but the car was a beast. On a 20° banked board track in Venice, California, Oldfield lost the race because he could not use the car’s full power. Then he ran afoul of the AAA again. Pickens arranged a race between Oldfield and the new heavyweight champion, Jack Johnson. The AAA called the race an “unsanctioned farce” and threatened a permanent suspension. Oldfield won the race and he and Pickens were immediately suspended by the AAA. Unable to run AAA races, Pickens and Oldfield began barnstorming. Oldfield would run the Blitzen Benz at county fairs, often against drivers on his payroll and setting records by small amounts so a new record could be set at nearly every event. Apparently barnstorming became tedious, and, by 1911, Oldfield had enough money to retire. He opened a saloon in Los Angeles with Jack Kipper called the Oldfield-Kipper Tavern. The saloon became very popular with movie and sports celebrities, but too much was happening in the racing world. De Palma was setting new distance records in his Fiat “Cyclone,” and, worse, “Wild Bob” Burman set a new land speed record in the Blitzen Benz at Daytona in April 1911. It was just too much for Oldfield, and he petitioned to get back in AAA. The new AAA chairman liked the idea of having Oldfield back and pushed he reinstatement through. Oldfield was back in racing for 1912.

First race for Oldfield was a 300-mile road race in Santa Monica in May 1912. Driving a Fiat, Oldfield was in second when a spring bolt broke, causing a 30-minute stop for repairs. He then ran as fast as the leaders until the Fiat threw a tire, causing a 13-minute stop. When he resumed, Oldfield ran 90 mph until an axle broke. Oldfield had lost none of his determination. His next racecar purchase was a 200 horsepower front-wheel-drive Christie. It was a beast of a car. Oldfield returned to barnstorming with it, setting new distance records. Attending the Vanderbilt Cup race in Milwaukee as a spectator, he became a driver when the driver of a Fiat crashed and was killed. Oldfield replace him and finished fourth in the 409-mile race. Hollywood’s Max Sennett gave Oldfield a taste of the movies in 1912. He was the hero in “Barney Oldfield’s Race for Life,” in which he raced a train to save Mabel Normand who had been chained to railroad tracks by the evil villain. Oldfield was not impressed with his performance, so one movie was enough for him.

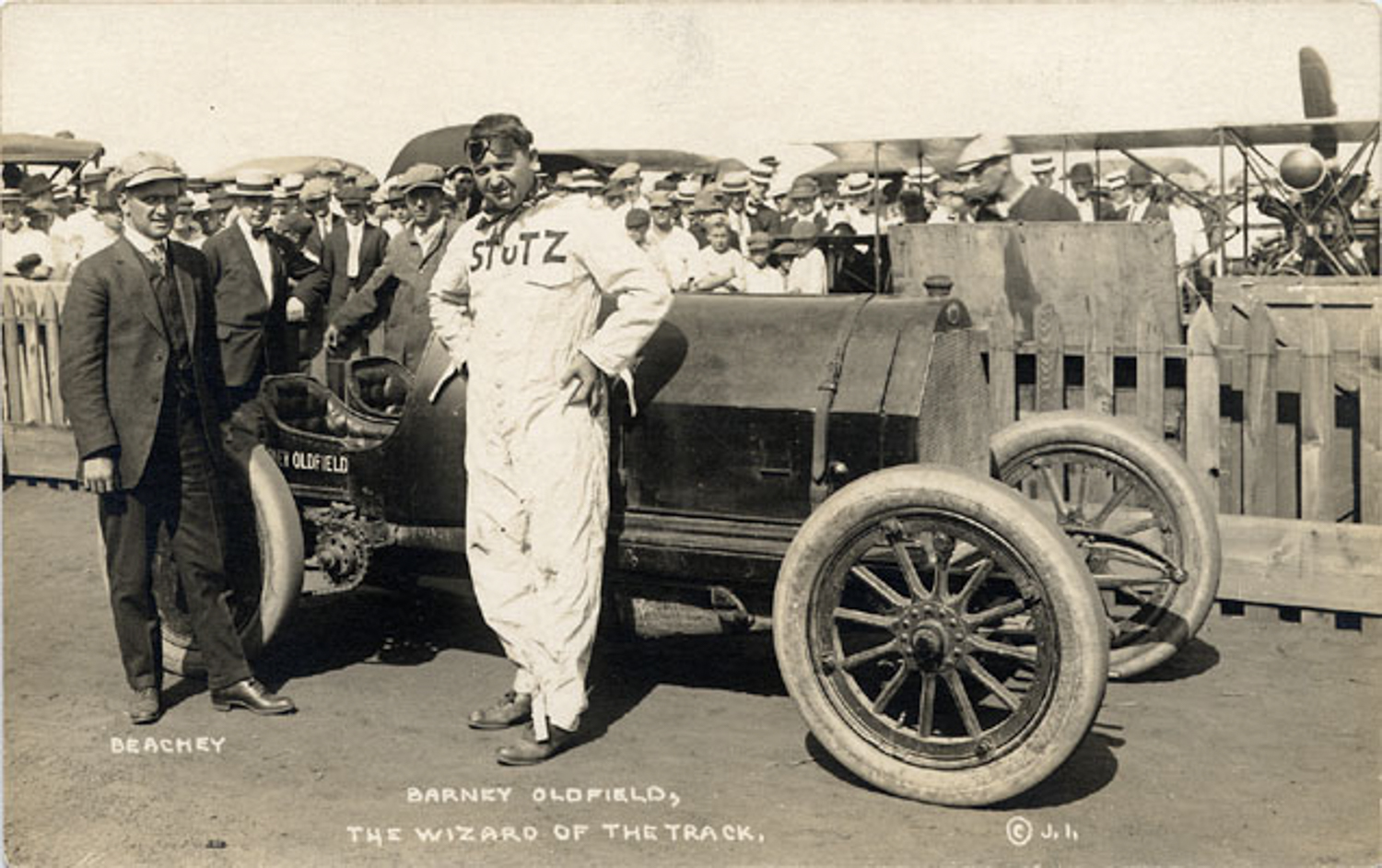

Together with his new “mechanician,” George Hill, Oldfield ran the Christie to wins, near misses, and a new 46.4 second mile at Bakersfield in 1913. The next year saw Oldfield run several different cars in a variety of races, some of which were carefully staged. One of the staged events that was very profitable was called The Championship of the Universe. Oldfield drove a Knox, a Fiat, or the Christie on mile horse tracks racing against Lincoln Beachey piloting a Curtis 40 horsepower pusher airplane. Pickens promoted Beachey as the “Master Birdman.” It was very profitable for all three of them. During 1914, they earned $250,000 split three ways. One of the more spectacular of the unstaged races was an event at Corona, California. Grand Boulevard was wide and paved, and it circled the city. Oldfield planned to run his Mercer at 90 mph. Earl Cooper tested in his Stutz and determined that a speed of 75 mph would save tires. Cooper was correct. Tires were a problem for everyone but him. Oldfield had to pass Cooper several times during the race – Oldfield was faster, but Cooper could run longer. Oldfield’s race ended when an excited young boy ran onto the track in front of him. Oldfield swerved to miss the boy, a wheel broke, and he crashed into some trees. A spectator suffered a broken leg, Oldfield’s mechanician was scalped, and Oldfield had minor injuries, but the kid was unhurt.

Oldfield and De Palma met again at the Vanderbilt Cup being staged in Santa Monica, and it proved to be quite a race. De Palma was to run a Mercer, but when he learned that Oldfield was hired to run a similar car, De Palma quit and prepared a Mercedes he had used to win the Cup in 1912. The race was 35 laps over an 8.4-mile course that included a three-mile straight. Fifteen cars were entered, but only five would finish. The Mercer was clearly faster on the straights, but the Mercedes was quicker in the corners. De Palma was the only driver who did not have to pit, resulting in he and Oldfield racing for the lead. De Palma took the lead when Oldfield had to pit with a shredded tire. Back on track, Oldfield caught the Mercedes at a rate of eleven seconds a lap during the last four laps, but De Palma was 200 yards ahead of the Mercer at the checkered flag.

Oldfield entered his first Indy 500 in 1914. He switched from a Mercer to a Stutz four-cylinder 434 cid engine. He qualified 29th of the 30 starters, and eventually finished fifth, the best finish for an American car and driver. He was not very successful in the Stutz, but he began to get negative press, which made him very grumpy. His wife, Bess, suggested he enter the Cactus Derby to show that he was still a tough competitor. The Derby was a run over a 671-mile route between Los Angeles and Phoenix. It was a race that Louis Chevrolet described as “the hardest event ever undertaken by a racing automobile.” Oldfield had entered the Derby in 1913 in a Simplex but had broken a driveshaft at Yuma, Arizona. This time he’d run he Stutz he raced at Indy, in an event usually run in stripped down stock cars. Oldfield was the fifth car away of the 20 entrants and led until a backfire caught his intake manifold on fire. The stop to put it out dropped him temporarily out of the lead. He was leading by over six minutes when the field reached the second overnight stop. The next day, he lost the lead when the Stutz died on a steep grade. Oldfield convinced a group of miners to push him to the top, and he was able to jump start the car on the downslope. A cut tire dropped him to fifth, but he was running strong again, and by the time the field reached Prescott, Arizona, the Stutz was 48 minutes ahead of the next car. The weather was horrible on the last day of the race. There were 134 miles to cover to the finish, and the New River was flooded. Oldfield tried to cross at what he believed was a shallow spot, but the car flooded and died. Time was lost until he found a mule team to pull him out of the river. Still, when he reached Phoenix, Oldfield won on elapsed time and was 36 minutes ahead of the second place car. He received a medal as the “Master Driver of the World.” His results in 1914 had him listed as fourth in the AAA Championship – his best result.

A switch to a Maxwell, and a modification that allowed the car to run on gasoline instead of kerosene produced very good results for Oldfield in 1915. Feeling very good about his performances again, he returned to partying hard. A night of drinking resulted in a hangover bad enough that he missed running in the Indy 500. The contract with Maxwell ended in 1915, and Oldfield tried a Bugatti, which proved to be slow, and had a wealthy friend, Dave Joyce, purchase a Delage for him. Unfortunately, the Delage wasn’t any faster than the Bugatti. Oldfield still had the Christie, with which he set a new lap record of 102.6 mph at the Indianapolis speedway. The Christie was an incredibly dangerous car to drive, so when Harry Miller was building the Golden Sub, Oldfield suggested that it have an enclosed cockpit, in theory to make it crash proof. The Sub was finally ready in June 1917. It was a streamlined beauty.

Oldfield looked through a rectangular porthole that was covered with a wire mesh. It was with the Sub that he and De Palma renewed their feud. De Palma raced a Packard Twin-Six, and the results were mixed for him and Oldfield. They raced at tracks from Chicago to Providence to Atlanta, and, after seven races, Oldfield and the Sub had won four. Oldfield was also setting records in the Sub, taking every record from one to 100 miles on dirt ovals.

A crash at Springfield convinced Oldfield that he no longer wanted to be in a closed cockpit car. The Sub crashed bad enough that the door stuck. Gasoline began pouring from the tank and ignited. Oldfield struggled with the door and finally pushed it open. He escaped with his pants, shirt, and hair on fire seconds before the gas tank exploded. After recovering from his burns, he thought he might try something a bit less dangerous and volunteered to be an aviator in the U.S. Army and fight in Europe. At 40, he was too old for the Army, so he had the Sub rebuilt as an open car. His first race with the topless Sub was in January 1918, when he beat Louis Chevrolet in his Frontenac. Oldfield also set new mile records in the car, but his race results were not what they once had been. He was slowing down. In September 1918, there was a call from the federal government to stop racing to save fuel for the war effort. The AAA agreed and suspended racing. Oldfield had a contract to race at several more events, and he did so, earning him another suspension from the AAA. Having already decided to retire, Oldfield was not concerned with the suspension. He won his last race on October 18, 1918, at Independence, Missouri, winning two straight heats on the half mile oval. Although suspended, the AAA listed Oldfield as eighth in the Championship for all time. He estimated that he had run 2000 events during his career and became a favorite of the public, who saw him as a “regular guy.” At events, he’d arrive for the race and yell, “You know me. Barney Oldfield.” It was always meet with cheers.

No longer racing, Oldfield did whatever would bring in some money. Harvey Firestone named a new tire line after him, creating the Oldfield Tire and Rubber Company, Inc. Oldfield received $50,000 for the use of his name and became company president. That lasted until Oldfield was in Cuba as a race referee, where he got into an argument about politics and was deported. Firestone bought him out to avoid any scandal. He spent a lot of time at races and regularly got into trouble in saloons because of his penchant for arguments and fights. He was still popular as a driver for record attempts. In May 1927, he drove a Hudson “Super 6” to a 1000-mile, non-stop record on a board track in Culver City, California. The record was 13 hours 8 minutes at an average speed of 76.4 mph.

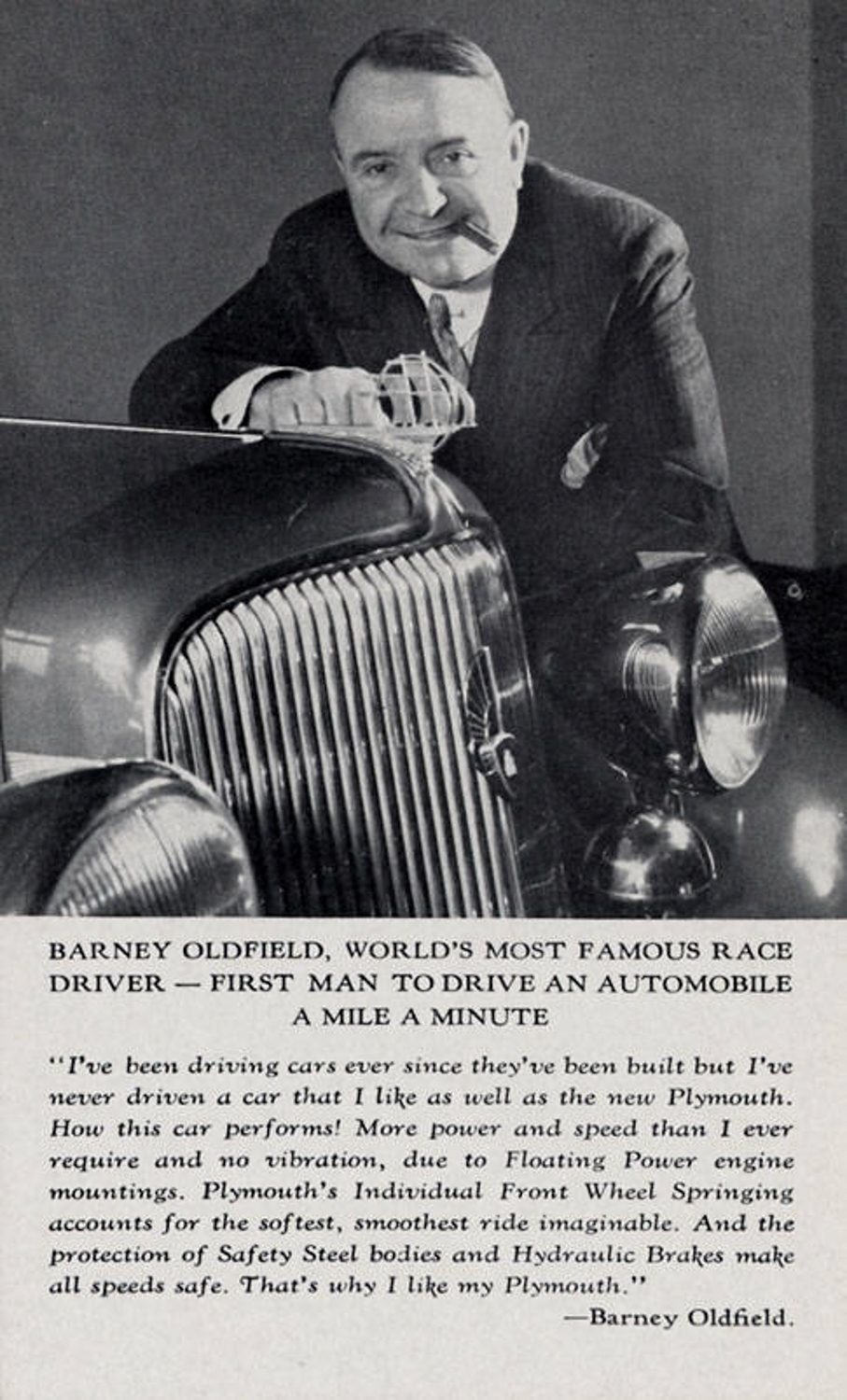

Until the stock market crash, Oldfield did well in the stock market. After losing much of his money, he resorted to stunts and jobs that parlayed on his continued popularity. He set a speed record driving a tractor, was a “highway advisor” for Plymouth, and, in 1937, opened the Barney Oldfield Country Club in Van Nuys, California. After WWII, he sold the country club and bought an oil lease in Oklahoma that didn’t produce, then settled in California. In May 1946, he was honored as an automotive pioneer at the Golden Jubilee of Automobiles in Detroit. Five months later, he died in his sleep from a cerebral hemorrhage. Oldfield was elected to the Auto Racing Hall of Fame in 1953.

Buick Country Club Coupe SN: 2210014

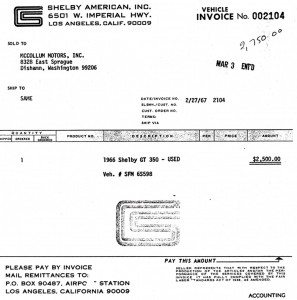

Oldfield’s home life was nearly as chaotic as his racing life. He was married four times, although to only three women. Bess Holland became his second wife after she helped him recover from a racing accident. His drinking and fighting caused her to leave him, and they divorced in 1925. Oldfield married a third time, but it was a difficult relationship, and it eventually dissolved in a divorce. Once again, Bess was there to boost his morale. She had never lost her affection for Oldfield, and they subsequently married again in 1945. It was for Bess that Oldfield bought a 1928 Buick Standard Country Club Coupe. Apparently, they remained close friends even though divorced. The car’s history might have been lost if not for Jeff Stumb, the car’s current owner.

Stumb is a car guy; one look in his garage validates that. He has also been the Director of “The Great Race” for the past 11 years. Stumb saw his first Great Race when it came through his town in Alabama in 1992. He participated in it for the first time in 1994 and did it annually for about 15 years. He became friends with Corky Coker, former owner of Coker Tires, who also participated in the race. By 2010, The Great Race was having financial difficulties, and Stumb suggested to Coker that if Coker would buy the race, Stumb would run it. What Stumb does now is move 500 people across the country in old cars. The Great Race is a turnkey event – participants pay one fee that includes all their food and lodging as they compete on a route that has been laid out by Stumb and his crew.

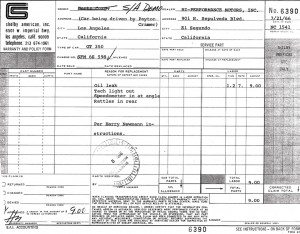

Stumb is always on the hunt for interesting automobiles, so when he saw an eBay auction for the Buick with a mention of Barney Oldfield, he bid. He was the only bidder, and he won the car for the starting price. Now that he had the car, he needed to find out its history. Stumb learned that Bess owned the car from new until her death in the 1950s. Attesting to its years of use, there is still a WWII gas ration decal on the car’s cowl. She and Barney had no children, so she left the car to a niece who had no idea what do to with it, so it sat in her garage. The niece had a mechanic, Joe Kotlar, who did house calls to maintain her daily driver. He saw the car and eventually was able to convince her to sell it to him in 1975. Kotlar did a full restoration of the car, in 1976, and kept the car in concours condition. He even found the original color somewhere on the car, so it is again in that color. It won its class at the Palo Alto Concours around 1982 and earned the Antique Automobile Club of America’s Senior Badge. In his 80s, Kotlar had an accident and hit his head. It caused him to realize that he could no longer care for the car, so he decided to sell it. Stumb was apparently the only person who viewed the auction who realized the importance of the reference to Oldfield.

The Buick is a Standard chassis with a 114.5” wheelbase, so a shorter car than the Buick Master cars of the same year. Buick’s total production of Standard Six cars was 76,596, of which only 13,211 were the Country Club Coupe. It is a lady’s car, at least compared to what Oldfield would have bought for himself. He would have wanted a larger car. But it had options that he would have liked, such as the cigar lighter and ashtrays for both driver and passenger. It had very rare #4 Buffalo wire wheels, side mounted spares, and both a rumble seat and trunk at the rear. The rumble seat had a key lock rather than more common handle/release. The car had a complete gauge package, including an ammeter, oil pressure gauge, water temperature gauge, drum speedometer, gas gauge, and clock. There’s also a clock in the rear view mirror. The gas gauge shows how many gallons are in the tank rather than a fuel level. The speedometer shows up to 80 mph, but Stumb has only driven it as fast as 40. “80 would be scary. It’s not quite a tour car yet.” For comfort, there is a heater for when it’s cold, and, during warm weather, the windshield raises from the bottom and the rear window comes down from the top to produce flow-through ventilation.

Driving Impressions

Stumb had found the best advance setting for starting the car, so it was already set when I got in. The interior and dash are very attractive; the gauges take you back to a much earlier time. To start the Buick, the key is inserted and turned so a button pops out. There is a switch on the button that is used to turn on the car. The starter is engaged by stepping on a large pedal to the right of the throttle, which looks like a button in comparison to the starter pedal. It takes a little choke when cold, but it starts immediately. Stumb’s driveway on the mountain where he lives is gravel and a bit rough, so we never got up to the 40 mph he has experienced, but I was able to take the car through the gears. Double clutching is the best way to insure smooth shifts. The car had no issue with the rough patches in the driveway, and was quite comfortable over them. Steering required a bit of muscle, making me wonder how Bess was able to manage the car. She lived in the Los Angeles area, so at least the city streets would have been smooth. Overall, it was an enjoyable experience to drive a car from the time before the Great Depression and one that had likely been driven by the Master Driver of the World.

Specifications

| Chassis | 114.5 inch steel chassis |

| Engine | Front mounted inline 6, removable head, valves in head, driving the rear wheels |

| Displacement | 3392cc/207 cid |

| Bore/Stroke | 3.1 inches (80 mm)/4.5 inches (114 mm) |

| Horsepower | 63 hp @2800 rpm |

| Torque | 140 ft-lbs (190 NM) |

| Induction | Marvel T3 carburetor |

| Transmission | 3-speed floor shift with reverse |

| Clutch | Dry plate, multiple disc |

| Steering | Worm and nut |

| Service Brakes | Expanding on four wheels |

| Emergency Brake | Contracting on rear wheels |

| Rear springs | Cantilever |

| Rear axle | Three quarters floating |

| Wheels | 31 inch steel wire |

| Tires | 31×4.95 inches |

| Weight | 3310 lbs/1501.4 kg |