“It was the best of times…it was the worst of times.” – Charles Dickens

PROLOGUE

I’ve forgotten more about my life in motorsports than most people have experienced. That said, recently my declining memory was stimulated big time by a news story focusing on NASCAR team owner Gene Haas’ plans to launch a Formula One team in 2016. Simple math brought me to a not- previously contemplated fact that 30 years ago (1985) another Haas—Carl (no relation)—was in the process of putting together the largest, most talked about and best financed American Formula One effort ever. Oh, how the memories—both good and bad—came flooding back…a virtual cornucopia of the best and worst motorsports insider experiences.

The saga started with a phone call from long time client Haas asking me to join him and Beatrice Companies CEO James Dutt for lunch, a meeting I went into cold regarding what to expect, and with minimal expectations. Was I wrong! After a brief introduction, I spent the next half hour mostly listening, and offering comment/guidance only when asked. I found Dutt to be focused, well-informed and experienced in launching major corporate identity initiatives, including multi-brand marketing efforts tied to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, the Chicago Marathon and the Chicago stop on the PGA Tour. On the other hand, he seemed somewhat naive about the intricacies and scope of motorsports, particularly Formula One. Most important, however, his simple philosophy regarding brand building—“Go bigger and better than the competition can even contemplate”—touched a positive nerve in one who always had to fight the client budget battle trying to execute what we marketing types call “The Big Idea.”

Overall Jim and I seemed to hit it off well. What I wasn’t prepared for was a personal phone call from the chairman of a Fortune 500 company later that afternoon with an unsolicited dream job offer almost impossible to refuse.

Unlike the racing program strategy employed by most firms, Dutt’s vision for Beatrice had the direct opposite focus. Instead of promoting a single product to the trade and ultimate consumer, his idea involved creating a common corporate halo over the myriad of brands it controlled. Beatrice, founded as a Nebraska dairy in the 19th century, was a behemoth consumer products conglomerate with offerings ranging from familiar grocery brands such as Hunts, Tropicana and Butterball to rental cars (Avis) luggage (Samsonite) and women’s undergarments (Playtex). In addition, the firm was a major independent bottler of Coca-Cola, and owned the nation’s largest network of cold storage warehouses serving not only its own needs, but those of competitors as well. Worldwide, Beatrice owned roughly 200 brands with significant distribution on five continents. In short, the company was a major player in many everyday aspects of human life. Yet, few people recognized its scope and prowess.

For Dutt, a 35-year veteran of the company who came up through the ranks to the top job, this represented both a problem and an opportunity. While virtually all of its brands had high consumer acceptance for quality, there was little, if any, overt Beatrice visibility at the division level. If they performed well, the individual company heads were pretty much left to their own devices. Jim’s vision was to capitalize on the combined image of the firm’s products by including more prominent Beatrice corporate identification in the form of a red/white ribbon logo on most of its product offerings. Dutt felt this corporate sub-branding would lead to a worldwide marketing synergy between the individual divisions, benefiting all parties via co-branding partnership promotion efforts, while simultaneously establishing the parent company as an international leader in quality consumer products.

The rollout of this approach started with title sponsorship of the Chicago Marathon and a major corporate/brand tie-in to the 1984 Los Angeles Olympic Games. While successful, Dutt kept looking for a marketing approach that would have both worldwide impact and a longer calendar of opportunity than offered by an event such as the quadrennial Olympics. One evening, while dining at his favorite Chicago eatery, Dutt entered into a casual conversation regarding his corporate vision with the restaurant’s owner Joe Marchetti. Marchetti suggested Dutt take a look at Formula One and offered the name of another friend, Carl Haas, as someone who could provide considerably more insight on the subject. A meeting was arranged and, as they say, the rest is history.

In my career, being faced with calendar-sensitive situations was commonplace, but none had the magnitude the Beatrice program spawned. From scratch, Haas was expected to have a European-based Formula One team up and running in less than a year, supported by a dedicated marketing infrastructure involving active participation by as many Beatrice-owned divisions as possible. Additionally, Dutt further complicated the situation by insisting Haas and Indycar team partner Paul Newman opt out of their secure Budweiser sponsorship in favor of Beatrice. This move would eventually help doom the effort (more on that later).

From a business operations viewpoint, Beatrice made the perfect choice in aligning with Haas. Widely respected as a no-nonsense, get it done motorsports entrepreneur, Haas not only operated successful teams in multiple North American championships, but also was the continent’s largest importer of racing cars and components. His Lola and Hewland distributorships, along with sales of other racing-oriented parts, provided the needed connections to the international infrastructure of key suppliers and people needed to undertake such an effort. Going into his first meeting with Dutt, Haas had no intention or raging desire to go Grand Prix racing. His plate was full. However, after listening to the Beatrice Chairman elaborate on his vision and financial commitment, Haas quickly negotiated a multi-year contract that would all-but-guarantee success if undertaken with his usual sense of detail and professionalism.

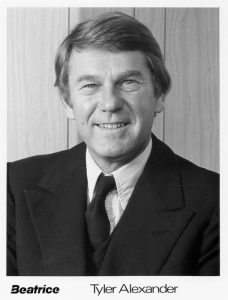

In putting his Formula One team together, Haas moved with lightning efficiency. Even before the contract with Beatrice was signed, he recruited two of racing’s best minds—E.E. “Teddy” Mayer and Tyler Alexander, ex of the Team McLaren efforts in Formula One, Can-Am and Indycars, to manage the day-to-day operations of the team. In turn, the duo began recruiting top talent from other World Championship organizations and British Aerospace, among other entities. Among those signing on was a bright young design engineer named Ross Brawn. . .you may have heard of him.

To drive the cars, Haas brought back two names from his championship years in the SCCA’s second incarnation of the Can-Am Series, 1981 Formula One champion Alan Jones, and former Ferrari race winner Patrick Tambay. This duo provided the team with a combination of excellent on-track skills and public relations savvy. When combined with the unsurpassed name recognition of Newman/Haas Indycar driver Mario Andretti, we had a triple threat opportunity both on and off the track. Having worked with all of them previously, I was thrilled.

Grand Prix racing is like no other motorsports form. It is a cloistered, secretive society populated by a breed of men who put Machiavelli to shame. Teams occasionally come and go, but the power structure of the sport today is controlled by the same wizard now as in 1985, a diminutive ex-motorcycle mechanic named Bernie Ecclestone. The catalyst for Eccelstone’s rise to ultimate power occurred in the late 1970s when the participants ceded worldwide television rights to Bernie in exchange for a shared piece of the action. This decision was shortsighted, but predictable. At the time, most team owners were struggling with rising costs and flat revenues. Eccelstone’s offer to fund the expansion and modernization of the then-underappreciated television business eliminated the need to invest precious capital in a necessary state-of-the-art studio and program transmission enterprise, plus offered the upside of additional income. Twenty-twenty hindsight notwithstanding, this was a critical decision far larger than anyone could imagine.

Ecclestone wasted no time maximizing on his television license. He poured money into studios, equipment and manpower, quickly building a network with a lock on every form of Formula One video content, including the live streaming of every GP race to more than 160 countries. While the team owners benefitted financially from the agreement, Ecclestone held the long-term key to the Emerald City vault and marketing power base. Practically speaking, as prosperous as the teams became because of Bernie, from a political standpoint they had about as much clout as the munchkins in the movie. But, this fact didn’t keep them from trying. Not a day goes by when one or more incidents or political misunderstandings roil their world. No wonder GP racing is so popular. The participants truly dislike each other, leading to an atmosphere where the teams’ off-track interactions often are more interesting than the show itself.

Even before we were officially up and running on the first day of 1985, I had developed and presented a marketing plan to elicit division enthusiasm in the corporate racing program. Free associate sponsorships with prominent on-car identification and client hospitality opportunities were offered in both IndyCar and Formula One on a race-by-race basis to those brands that jumped on the marketing bandwagon. This plan called for zero added spending, but necessitated a reallocation of a small percentage of the existing division marketing budget to support the promotion effort, plus a willingness to participate in the corporate identification mandate. Each brand-marketing director also received a promotional idea book to stimulate tie-in creativity with complementary Beatrice brands. Again, more later.

Photo: BRDC

A Fast Start—A Giant Letdown

While Mayer, Alexander, Brawn and a host of other top Formula One hands worked tirelessly to assemble a factory near Heathrow Airport and design a car, our newly recruited group’s task was to sell the program internally both in the USA and overseas. The divisions’ reception of our efforts could not have contrasted more. Offshore, the GP sponsorship was nearly universally hailed as a stroke of marketing genius. The Indycar effort, however, offering the same list of benefits to participating brands, met with more questions than acclaim. Unbeknown to our corporate promotion group, the operating heads of several U.S. divisions were in active off-the-record conversations regarding Dutt’s plans. They were comfortable running their individual fiefdoms and didn’t take kindly to what they perceived as central office interference. Furthermore, many in this group were put off by what several characterized as Jim’s heavy-handed approach to the subject. They felt pressured and thus, rather than embracing the big picture, displayed concern both individually and collectively. A key focus was the size of Haas’ contract, which called for base support of some $75 million over a period of five years. While there was some moderate support in a few U.S. corner offices, most of the powerful division leaders chose to disagree with both the medium and the cost without examining the facts. And, they voiced their opinions all the way up to Dutt’s fellow corporate directors, further stirring the pot.

Had we been able to focus exclusively on Formula One, I believe to this day the effort would have been a grand slam success. My opinion is backed by the documented business benefits GP racing sponsorship delivered internationally. This, in turn, would have resulted in positive feedback to the Stateside doubters. Furthermore, these successes would have stimulated a movement toward universal acceptance of the Beatrice ribbon identification on all products. On the other hand, the late-to-the-game Indycar effort, rather than being a preview catalyst of all that is good about racing sponsorship, turned out instead to be a festering sore in the minds of enough key influencers to eventually bring down Jim Dutt, our program and, ultimately, the company. This occurred despite the first-rate performance of everyone associated with the Indycar program. It was simply too “in your face” local to stop a festering rebellion.

For Want of an Engine

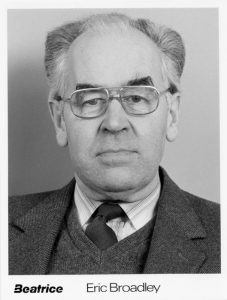

As work progressed at warp speed on the first Beatrice F1 chassis, designated THL-1 (Team Haas Lola out of loyalty to Haas’ great friend and car builder Eric Broadley, although he had little influence on the design), optimism ran high. Brawn and his design team were onto something big. There was just one minor problem—no engine agreement had been secured.

Today, this would not be an issue since engine manufacturers competing in the World Championship are required to share their power plants via lease or sale with up to four competing teams. As an example, look at Williams’ improvement last season as the result of acquiring the use of Mercedes horsepower. Three decades ago this rule didn’t exist and exclusive engine use by the house team was common. Still, we were optimistic.

Ferrari, Porsche and Ford were the prime targets for power plants. Mario Andretti personally contacted Enzo Ferrari and arranged a meeting in Modena with himself, Dutt and Haas. They presented credentials and thoroughly outlined their plans. Il Commendatore was a gracious host (he even bought lunch at his favorite local restaurant), but soon after turned down the Beatrice request. From there it was on to Stuttgart for a similar meeting with the same results. It seemed while Formula One was outwardly welcoming to the American team, none of the players had any desire to assist a new deep-pocketed competitor. Draw your own conclusions on the reasons why.

Concurrent with the above visits, Haas approached Ford, and several positive meetings were held in Dearborn. Though not initially excited, Ford soon warmed to the idea of two great American companies with extensive international interests working together on numerous consumer promotions. However, there was a fly in the ointment. Ford would be unable to develop and deliver an all-new Cosworth-built GP engine before the 1986 season. That meant the Team’s inaugural power plant would have to be a stopgap that could be quickly produced using commonly available components. This led to a reluctant decision to commission British engine builder Brian Hart to build the power plants for the few 1985 events we would enter—starting with September’s Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Hart, respected as a top engine builder for small displacement sports racing and formula cars, gave it the old college try. However, while trying to squeeze near-competitive horsepower from what was essentially a parts bin design, he succeeded in creating a classic “nickel rocket” that proved to be embarrassing for all parties. While internal anticipation of our early results was muted, there was more than quiet optimism about 1986 and beyond.

Begin Part 2

“Is It June yet???” was the slogan on a pin distributed by Newman/Haas PR manager Michael Knight to generate conversational activity during one particularly boring month of May in “Naptown.”

The contrast between the Indy 500 of 1985 and today’s event could not be wider. The Memorial Day Classic was then one of the world’s great sporting events, attracting not only a sellout race day throng reported to be in the 400,000 range, but an additional 150,000 spectators for pole day and more than 25,000 for each day of practice. The event was also a media magnet, covered by reporters from virtually every major news organization in North America, Europe and South America. Indy was even deemed important by the world of Formula One, although participation by World Championship drivers and constructors had waned due to scheduling conflicts with the Monaco Grand Prix—another situation from which you can draw your own conclusions.

From our perspective, the drawn-out month of May appeared to be the ideal coming-out party. While our F1 car was in the final stages of design and production, the Newman/Haas sponsorship provided both a strong on-track and media presence…the perfect platform to both launch and test market our promotion formula. Here, some pioneering was necessary. Believe or not, the Speedway at that time had no “official products” outside the automotive segment. I quickly sold Indy’s marketing group on the benefits of consumer product tie-ups and made the first-ever deal for our hot dog brand, Eckrich. This included the sale of 50,000 pounds of product to the Speedway for category-exclusive sale throughout the month of May, use of the Indy 500 logo for all retail packaging and Eckrich point-of-purchase materials at every concession stand and at retailers throughout a five-state area where known interest in the race was historically highest. Consumers were also invited to enter to win tickets to the 1986 race. Finally, Mario’s car carried Eckrich associate sponsorship with signage on the highly visible engine cowling. Did it work? Documented sales results showed a 142-percent sales increase vs. the same period the previous year.

But, there’s more! Working with Beatrice’s ad agencies, a national newspaper insert promoting individual brand ties to the parent company and the race was distributed during the week leading up to Memorial Day. This dovetailed perfectly with an internal campaign whereby Chicago area employees were invited to participate in a pre-race outing to Indy, including a Gasoline Alley tour and a Q&A session with Andretti and Paul Newman. I don’t know who was the bigger draw, Mario or Paul, but the tour sold out with many more on the waiting list.

I would be negligent if I didn’t mention we also planned for a possible Indy victory. Win ads were on standby at major newspapers and enthusiast/trade publications. Post-event appearances by Mario were penciled into his schedule. Everything was in place—except fate.

The race will long be remembered for one of the most bizarre happenings in the history of the Speedway. Danny Sullivan’s “Spin and Win” incident while battling for the lead with Mario confounded even the most jaded of pundits who saw it happen. It was a 1,000 to 1 shot that left everyone all but speechless. On lap 128 Sullivan and Mario were in a classic duel between Indycar racing’s two best teams, Penske and Newman/Haas. At the end of the main straight, going into Turn One, Sullivan ducked below the white line (legal then) to get inside of Andretti and take the lead. Andretti tucked in behind him with a cunning move and closed to within a foot of the lead car, taking the downforce-creating airflow off Sullivan’s machine. The result was predictable: Danny lost grip, wiggled and spun smokily toward the outer wall in the short chute between One and Two. That’s when the improbable happened. Instead of tapping the wall, Sullivan’s car spun in a tight circle—either pure luck or a moment of miraculous driving—and missed the wall, so that he regained control down near where the infield grass meets the asphalt. Even more amazing, no other competitor touched Sullivan’s car! He gathered himself together and motored around to the pits under the guise of the yellow flag caused by his “moment.”

Initially, Mario thought his most serious competition for the win had been eliminated. He was as stunned as everyone else when his crew radioed that Danny was in the pits getting fresh tires. As it turned out, it wasn’t just any set of tires, but a perfectly matched set from which he would profit mightily during the remaining laps. Tire technology in the 1980s—even after a brutal “tire war” between Firestone and Goodyear—was a far cry from today. Slight variations were common in the same-size bias-ply tires, a condition that clearly affected driveability. Sullivan’s new set just happened to be nearly perfect, while Mario took on four more typical tires during his pit stop. When the green came back out, Sullivan easily reassumed the lead and finished 1.75 seconds ahead of a hard-charging Mario. ABC’s Jim McKay summed up the final lap by extolling the efforts of two American heroes, with the new hero on this day taking the measure of the old hero.

Jim Dutt and I were watching the last laps of the race on the Speedway feed in the team motor home area. When the checker waved, I leaned over to him and said, “For the want of less than two seconds, we could have paid for the entire program today.” Jim said nothing, just nodded his head with a distant expression. Today, I know he had far more important things than winning Indy on his mind, the culmination of which would come some 60 days later.

While Beatrice didn’t win the race, we did win the visibility battle, proving the racing-oriented marketing support program our group developed was not only effective, but repeatable with only individual market adaptations.

When I returned to my office in mid-June following the Milwaukee Indycar event and a Formula One planning trip to London, the corporate rumor mill was buzzing about Dutt’s future as chairman. Despite our obvious successes, the negative vibes concerning the racing effort seemed to intensify daily. Citing excessive expenditures; centrally dictated brand budget allocations and a feudal management style coupled with a lack of personal accessibility (Dutt traveled constantly working on acquisitions), the now-energized group of discontented top division executives went to the board of directors in force, demanding change. In July, the board—which included several of the accusers—terminated Jim unceremoniously and brought in Bill Grainger, a retired former chairman, to act as interim gatekeeper until new leadership could be selected. However, after only seven months from the day I arrived, in the back of my head there was a gnawing feeling that things were about to change big time.

Monza: A Big Moment Turns Into a Cameo

Despite the misgivings regarding the future, the buildup to our Formula One debut could not have gone better. Every international division of substance enthusiastically jumped on the sponsorship bandwagon with tangible results. In England, the Beatrice Butterball brand scored both new accounts and built existing business to record levels. In Italy, Avis and Samsonite, headquartered only five miles from each other in Milan, were introduced for the first time, resulting in a countrywide merchandising program of logical promotional partners. Even Beatrice’s low-profile frozen fish division got in on the action, opening doors historically closed to their sales efforts. Combined with the issuance of Formula One’s first official pocket media guide and sponsorship of the Press Association’s annual dinner at Zandvoort two weeks before our Italian Grand Prix debut, expectations were running high—far higher than reality.

Our inaugural on-track foray was a one-car effort with Alan Jones. As a recent World Champion, the fast-quipping Aussie was a media darling. Australia’s National Sports Channel flew a crew to Monza to cover every move of one of the country’s true national heroes, and the buzz around the paddock was all positive. Then came the moment of truth. While the car looked sensational and had shown amazing handling and aero characteristics from the outset, the aforementioned engine issue erupted within the first minutes of practice and persisted the entire weekend. While we did make the race, our once buoyant optimism turned to a wish for just a little luck. Jones was so frustrated that when asked by the Aussie media for a post-race live interview, he quipped that he would probably be ready to talk in the paddock about 20 minutes after the green flag waved. He kept the appointment.

Despite the egg-laying coming-out party, international enthusiasm for the program continued unabated. Beatrice’s Australian divisions jumped in with both feet and created a national merchandising/sweepstakes program around the upcoming Formula One event. In Brazil, two divisions combined resources on a program that included near-lifesize replicas of the F1 car for in-store display purposes. Combined with an all-out effort to wring reliability, if not competitive horsepower, from the existing Hart engine and confirmation that Carl’s efforts to partner with Ford had borne fruit for the 1986 season, things were good at the same time they were bad. As a group, we just kept our heads down and continued to march at a double-time pace.

Don’t judge a book by its cover. We all have heard the stories—including the recent $100-million settlement with the German Government to walk away from a $44-million alleged bribe conviction. Say or think what you want about the man, but I found Bernie Ecclestone to be a focused and pragmatic businessman. When our group head Lee Reiser and I met with Ecclestone at his Brabham team headquarters to discuss a major U.S. media program we were developing around Formula One, he didn’t hesitate for a second to grant us the exclusive U.S. rights to televise four 1986 Formula One events as same day coverage prime time specials. The goal, with sponsorship from Beatrice, Ford, Goodyear and Shell (our major FI partners), would be to create programming that would not only chronicle the events, but showcase the surrounding scene and educate the audience about the magnitude and intricacies of the sport.

The best part of the deal we discussed with Bernie was that no rights money would change hands. While Formula One Television would provide the race feeds and images, we would negotiate the U.S. television package and develop mutually approved in-program features. Ecclestone was candid about his reason for such implied generosity. The U.S. was the organization’s problem child both in terms of TV audience and venues. We shared a common vision that this approach, backed by appropriate merchandising, could go a long way toward dramatically building U.S. interest in Formula One. Oh, what could have been!

The Inquisition—A Wake Up Call

With Jim Dutt regretfully out of the picture, our only conduit to corporate information was Lee Reiser. Normally a bundle of optimistic enthusiasm, by autumn even he was getting worn down by the intramural politics being played on the top floor of Two North LaSalle. This all came to a head just prior to the Australian Grand Prix when I was told to go to Laguna Seca for the Indycar event rather than Down Under. The reason given was international travel had been banned except for “vital needs.” Apparently, a continent-wide marketing program tied to the Melbourne race was no longer considered relevant upstairs. Lee, ever the gentleman, quietly told me to “get out of town.” Given the circumstances, I was only too happy to comply.

If the above marked the beginning of the demise of our program, a phone call shortly after my return from California, confirmed my worst suspicions. Along with Reiser, I was invited to make a presentation regarding the program to the new chairman and select members of the company’s board of directors.

We came loaded for bear with a presentation covering everything from the creative development of the program to its many successes and future plans. There was, however, one problem. Despite our best effort, no one in the room was really listening. At the end of the presentation, the audience was coolly polite, but unmoved. Then I had a revelation—our program wasn’t the subject of the meeting! This was clearly a witch-hunt directed at trying to implicate Jim Dutt. I was flabbergasted at the veiled accusations presented and told the inquisitors so in no uncertain terms. Only Lee Reiser, ever the mediator, kept me from going further. I’ll always be grateful to him for his intervention.

Clean Out Your Desk and Have A Nice Day

Fall turned to winter in 1985. While we were still operational, our planning for a massive worldwide 1986 marketing campaign built around the racing teams was being openly roadblocked. The Formula One television package and all in-country division tie-in programs were put on hold with no explanation. We went to work, but got about as much done as a Chicago political payroller. Both racing teams continued to operate as if nothing had happened, but behind the scenes there was a level of tension that cannot be put into mere words. Every aspect of the effort suffered, but none more so than the tenuous relationship with Ford. While the new Cosworth-built engine program was on schedule for the 1986 season, the Dearborn enthusiasm level waned by the day with the realization the marketing promises of the Beatrice relationship were turning to dust. Carl Haas did a masterful job keeping things together, but privately acknowledged the handwriting was on the wall.

The first overt sign of the program’s problems occurred when the team failed to show for the annual winter Goodyear Formula One tire test in Brazil. The major reason for this miss was simply a matter of engine availability. The new Ford twin-turbo wasn’t ready. But, reality and perception are two different things. The international media jumped all over the story. Conjecture about Beatrice’s future sponsorship ran rampant. In Chicago, the corporate types shrugged the whole thing off, that is, until their two biggest Brazilian-based divisions complained loud enough about how coverage of the Formula One team’s absence from the tire test session was hampering their planned countrywide merchandising program’s credibility—including the aforementioned life-size in-store car displays.

At precisely the time this happened, most of our group, including yours truly, were reviewing and signing our employee separation agreements. I had processed out and was packing my things when the phone rang. Would I come to a meeting on a crisis situation dealing with Formula One in Brazil? After gently reminding the caller I was no longer an employee, I took the meeting as a paid consultant and was quickly dispatched to Rio to fix the mess. The result was a temporary calming of the media hurricane, but the die was cast. Kolberg, Kravitz and Roberts, one of the nation’s major leveraged buyout firms (later the subject of the movie Barbarians at the Gate), had announced a $6.2 billion takeover offer for all of Beatrice, the largest deal of its kind to date. In an ironic twist of fate, Chicagoan Don Kelly, the former chairman of ESMARK—a company acquired by Beatrice on Dutt’s watch—was selected to run the firm. One of his first moves was predictable—eliminate the corporate identity effort and find a way out of the motorsports and Chicago Marathon contracts. Ironically, Kelly stepped up big time to become title sponsor of the aforementioned PGA Tour event, raising the corporate commitment to golf from less than $100,000 to multiple millions. In making the decision, he was quoted as saying “I love golf, but I can’t run a block.” Every dog has his favorite toy…

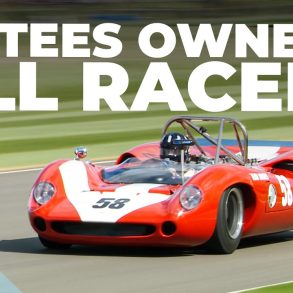

The contract settlement between Beatrice and Haas took several months to negotiate at an unpublished figure reported to be in the $25 million range. The Formula One effort continued throughout 1986 and proved its mettle by scoring World Championship points before ceasing operations when—not surprisingly—no other sponsor could be secured. All but one of the cars and the team support equipment were sold. The remnants of the team were recently advertised for sale as a historic turnkey racing package by their Australian owner. What had been touted as one of racing’s premier corporate marketing efforts became just a memory in a few peoples’ minds…dust in the wind.

Epilogue

The world of Formula One Gene Haas is entering has changed dramatically over the past three decades as evidenced by his recently announced technical affiliation with Ferrari. Today, things unavailable at any price to Beatrice can be leased or purchased if one’s pockets are deep enough. Additionally, many U.S. companies with international marketing ambitions are dipping their toes into F1, including Hewlett-Packard and UPS among others. Still, serious questions remain. Only weeks after the Gene Haas/Ferrari announcement, Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, Ferrari’s patrician long-time CEO and keeper of Enzo’s flame, was forced out by parent company Fiat/Chrysler in the wake of a disagreement over future road car production volumes. Subsequently, Fiat/Chrysler announced the Prancing Horse brand would be spun out from the parent as a separate entity, essentially taking them off the controlling company’s books. While there’s no doubt in my mind Ferrari will remain a stalwart of Grand Prix racing, the winds of change are in motion in Maranello, a factor that could have major long-term ramifications on Haas’ pending relationship.

I also wonder what will become of the Grand Prix of the Americas once Rick Perry is no longer governor of Texas. The Austin race is pure Perry. He’s a big-as-Texas personality who has invested untold millions of Lone Star tourism revenue into securing the event. Will his successor be as enthusiastic, or will Bernie again have to seek a new site and promoter in a country that remains perhaps his biggest marketing challenge?

As an interested spectator, I wish Gene Haas nothing but success. On paper, he’s the perfect Formula One team owner, a billionaire who controls a privately held, industry-leading company. He has the rare advantage of cash flow without the requirement to please stockholders and Wall Street. In addition, he seems to possess a Larry Ellison-type ego—Ellison, founder and chairman of technology giant Oracle, is the defending America’s Cup yacht racing champion—one who always wants to compete at the zenith of the food chain with little regard to cost. If anyone can pull it off, Haas seems to be a likely candidate.

Haas is currently experiencing the glow of glamour and recognition of a newly minted World Championship entrant. However, no matter how well thought-out his plans may be, there will be many unforeseen roadblocks. This realization probably led him recently to delay his team’s entry into Formula One by a year. Long term, Haas must be prepared to deal daily with more political intrigue, backbiting and trickery than NASCAR could produce in a month of Sundays.

I hope he’s also committed to being personally on site a good deal of the time and that he is able—like his earlier namesake—to attract extraordinary people to implement his dream. Otherwise, like the guy who optimistically goes to Las Vegas in a new wardrobe and returns home in a borrowed diaper, he’s in for the surprise of his life. My hope is that he succeeds while maintaining his billionaire status. After all, no one wants to be just another millionaire.