Coachbuilding is the art and science of producing bespoke bodywork installed on a pre-assembled chassis with the art as timeless as the motor car itself. Mass production has practically extinguished the practice; however, coachbuilding lives on with Rolls-Royce at the forefront of its rejuvenation.

With greater than a century of experience and modern-day Bespoke capabilities, the marque has redefined the coachbuilding movement. Rolls-Royce has long been used to being able to commission all parts of their motor cars’ features and specifications. Now, more than ever, Rolls-Royce clients are looking for opportunities to go beyond Bespoke and define the physical form of the motor car.

Coachbuilding Origins

There were only around 8,000 registered motor cars in Great Britain when Charles Rolls and Henry Royce met in 1904. It was a modest number compared to the half a million horse-drawn carriages at the time.

Within 20 years, the coaches and carriages that had ruled the roads for more than a century have practically vanished. The motor car was no longer a novelty nor exclusively for the wealthy, it had matured into the universal means of private travel.

In the early days of the automobile, manufacturers commonly produced only mechanical elements. The ‘rolling chassis’ were sent to specialist coachbuilders who would then attach the bodywork according to the specification of the customer.

There were some coachbuilders who simply shifted from creating horse-drawn carriages, while others capitalized on the opportunities presented by the motor car.

The pre-Edwardian car bodies were constructed similarly to the horse-drawn carriages. It soon became apparent that the methods and materials that were well suited for the pace of the horses could not keep up with the speeds of the motor car which were now traveling up to 40 miles per hour. The art of coachbuilding demanded a more scientific approach to adapt.

History of Coachbuilding with Rolls-Royce

In the early 1920s, mass-market carmakers commenced establishing in-house coachbuilding so engineers could address distinct issues from an automotive application like torsional stress and vibration.

For the next few decades, Rolls-Royce and other luxury marques nevertheless remained outsourcing the coachwork to specialist houses.

Rolls-Royce clients could still have their rolling chassis transferred to the coachbuilder of their choosing. The coachbuilder would then design and build a car body from the specifications given by the client, much like ordering a dress from a Paris couturier or a suit from a Savile Row tailor.

Up until the 1930s, most coachbuilders kept the tradition of assembling a wooden frame, normally in ash, wherein aluminum or steel body panels were either welded or pinned. The process helped the coachbuilders produce essentially any shape.

The design of the coach bodywork was commonly based on the customers’ requested fittings and interior space.

As their experience grew and new materials for coachbuilding were discovered, coachbuilders had to adapt their practices, with the later frames shifted to metal tubing or angle-iron.

The traditional way of coachbuilding lived on until the introduction of the semi-monocoque construction, with sub-frames for the mechanical components.

The new process made it impossible to do anything more than the simplest adaptations to the body design. For Rolls-Royce, the shift did not occur until October 1965, when the Silver Shadow replaced the Silver Cloud series.

For Rolls-Royce, though, coachbuilding continued. The Phantom VI, which was constructed on a separate chassis, was still in production, although in reduced numbers until 1993. The coachwork was fulfilled by Rolls-Royce subsidiary, H. J. Mulliner, Park Ward Ltd.

The Priniciples of Body Design

Theoretically, a coachbuilt Rolls-Royce could be any shape that the buyer fancied. In practice, however, there were constraints. Rolls-Royce motor cars were designed using the proven technical beliefs that in the minds of the Company’s founders, were completely inviolable and unarguable.

Possessing a strict rule on the untouchable dimensions of the bulkhead behind the radiator, Rolls-Royce was able to ensure that the essential proportions of the bodywork were retained and the automobile could be quickly recognized visually as a ‘true’ Rolls-Royce.

To this day, the proportions are still enshrined in the marque’s design tenets. Any contemporary Rolls-Royce has the 2:1 ratio of body height to wheel diameter which was initially established in 1907 with the Silver Ghost.

Three fluid lines running the length of the car defines the body shape. The ‘waft line’ gives the sense of movement to the car, the ‘waist line’ gives presence and purpose, and expressing its individual character is the silhouette.

The basic principles still give considerable freedom, as seen in the very distinctive forms of the Cullinan, Dawn, Wraith, Ghost, and Phantom. This gives both the client and the designers considerable creative freedom during the coachbuilding project, even within the design parameters. The car will also bear the Spirit of Ecstasy figurine on top of the grille.

Legendary Coachbuilt Rolls-Royce Motor Cars of Yesteryears

40/50HP Phantom I Brougham De Ville (1926)

The renowned coachbuilders of the past gave the same consideration to the interior as the exterior of the cars they designed. One of the key elements of the automobile was the instrument dials, which went beyond merely conferring important information to become a miniature work of art.

In 1926, Charles Clark & Son Ltd of Wolverhampton for Clarence Warren Gasque, a London-based American businessman with French ancestry, built the 40/50HP Phantom I Brougham De Ville to be given as a gift for his heiress wife, Maude.

Gasque commissioned the interior to reproduce the Rococo ambiance of a salon in the Palace of Versailles. It was fitted with a polished satinwood veneer paneling, a painted ceiling inspired by Marie Antoinette’s sedan chair, and Aubusson tapestries.

The car was also given an exquisite French ormolu clock which was mounted on the partition between the front and rear cabins, an exceptional detail that showcases the peak of the instrument maker’s art.

17EX (1928)

By 1925, Royce was a bit troubled that some of the coachwork fitted to the chassis may be influencing the performance of the car due to the former’s weight and size.

To resolve this, Henry Royce created an experimental Phantom with a lightweight, open, and highly streamlined body. Named 10EX, it became the foundation for a series of cars that gave new insights into decreasing air resistance, which was a huge leap forward in automotive design.

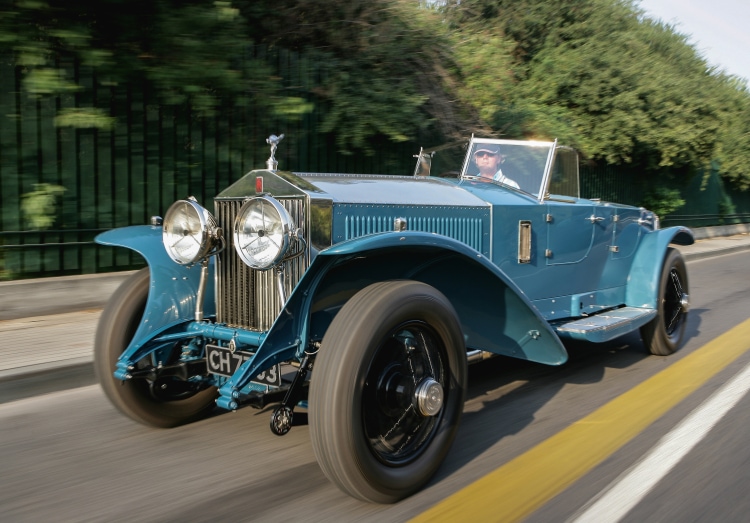

The 17EX was the fifth in the series, was completed in January 1928, and could achieve speeds beyond 90 miles per hour. Since Royce insisted that even experimental cars should look as good as the others that carried his name, the example had a blue finish following the exact standards of the marque.

According to modern color psychology, blue is linked to trust, dependability, calmness, and stability. The color is also very visible at speed, as shown by the record-breaking cars and boats of Sir Malcolm Campbell, Royce’s good friend.

Phantom II Continental Drophead Coupé (1934)

Co-creation has forever been at the center of coachbuilding. Upon commissioning a design for the perfect motor car, the customer would work with designers and manufacturing specialists to create a technically achievable final design. It is only then that the coachwork would be made and completed to the customers’ specifications.

A F McNiel designed the 1934 Phantom II Continental Drophead Coupé, and it was constructed by Gurney Nutting & Co in London.

The example is arguably one of the most exotic and beautifully balanced boattail coachworks that have ever been produced.

The rear sweeping concave curves rise upwards towards the razor-edging of the varnished rear decking. It has a design that has stood against the test of time and is still considered a great example of sporting elegance.

It is also interesting to note that John Blatchley, McNeil’s successor and protégée designed two of the most successful Rolls-Royce models of the 50s, 60s, and 70s: the Silver Cloud and Silver Shadow.

Phantom VI limousine (1972)

The Phantom VI was the last Rolls-Royce model that was produced with a separate chassis. It was designed and built by a wholly owned subsidiary of Rolls-Royce, H. J. Mulliner Park Ward Ltd.

Like a modern-day Bespoke Collection car, the example was based on a production model but had several added features that the customer had stipulated.

The example enhancements were so lavish and comprehensive that the marque actually created a special promotional brochure based on the example for prospective clients, as it showcased the bespoke capabilities of the marque.

The car was equipped with a state-of-the-art sound and television system, a fridge for chilling picnic food and wines, flower vases, and even a burled walnut picnic tables.

The tables were stored in the boot and could be attached to the front wings for alfresco dining, where the passenger and driver are perched on a couple of ‘toadstool’ seats clipped to the front overriders.

Sweptail (2017)

In 2013, Rolls-Royce was assigned to build a coachbuilt two-seater coupé possessing a large panoramic glass roof. The vehicle was inspired by the beautiful coachbuilt motor cars from the marque’s golden era during the 1920s and 1930s.

The example was the first fully coachbuilt Rolls-Royce produced in the modern era. The defining feature of the example is the raked rear profile, the roof-line tapering in a sweeping movement to a ‘bullet-tip’ that incorporates the center brake light.

The bodywork of the example wraps under the vehicle, and like the hull of a racing yacht, it has no visible boundary to the surfaces. The underside of the motor car has a progressive upward arc at the rear departure angle, creating the swept tail that the car’s name was derived from.

When it made its debut in 2017, the clean lines, as well as the grand, contemporary, and minimalist handcrafted interior of the Sweptail gave it international acclaim.

The motor car took four years to make and is now considered a true modern classic and one of the greatest two-seater intercontinental tourers globally.

[Source: Rolls-Royce]