In retrospect, the end of the 1973 Can-Am championship was the pinnacle of the series. Porsche’s turbocharged “Panzer” 917/30 had handily claimed the championship, though Don Nichols’ dark and mysterious Shadow cars were finally beginning to live up to the promise they had shown over the preceding three years. No one would have guessed, however, that over the course of the following 12 months Shadow would build arguably one of the best Can-Am cars of the series, or that the series would completely implode due to political machinations, both internal and external. Even more strangely, the rise of enigmatic team owner Don Nichols’ Shadow cars and the near simultaneous collapse of one of the world’s greatest racing series share an extremely bizarre 16th century connection…Niccoló Machiavelli. In order to fully appreciate how all these disparate pieces fit together—along with an internecine battle between three designers and two drivers—it’s necessary to start with the single shadowy figure who unifies them all, Don Nichols.

Spooks & Shadows

There is perhaps no other figure in modern motorsport more shrouded in secrecy, misinformation and innuendo than Don Nichols—and that’s the way he likes it! Reports have labeled him a spy, a CIA agent and a war hero who not only fought at the Battle of the Bulge, but also saw action on D-Day. Whenever asked, Nichols always responds that he can’t or won’t talk about his past, only further feeding the flames of wild conjecture. What is known is that Don Nichols was born on November 23, 1924. During World War II, Nichols studied Japanese at the army’s language school in Monterey, California, and subsequently joined the Army’s Intelligence Corps as a translator. Nichols was stationed in Japan, after the war and eventually, as the country recovered, he saw an opportunity to both make some money and indulge one of his passions, auto racing. Nichols began by importing racing parts to Japan. Not long after, he was able to negotiate a deal to become the Firestone tire importer for Japan. During the early 1960s, Nichols’ influence in Japanese racing circles was such that he also became involved in the creation of the Fuji International Speedway, which opened in 1965.

By 1967, Nichols decided he would move back home to California. However, the following year, he made arrangements to ship a Lola T-70 back to Japan for Pedro Rodriguez to drive at Fuji, only he needed to have a fresh engine installed in it first. This led Nichols to the Santa Ana, California, shop of a young, budding designer named Trevor Harris. Over the course of the job, Harris shared with Nichols his idea for a radical, new Can-Am car. Harris’ concept was to create an extremely small and low, high horsepower Can-Am car that had such a low frontal area that it would cut through the air like an arrow. As Harris explained to Nichols that this “Knee-high” car would potentially have a terminal top speed far in excess of anything previously seen in the Can-Am, Nichols began to see the potential. Soon the duo agreed to build the car together and campaign it in the 1969 Can-Am series.

As a result, Nichols started a new company that he dubbed Advanced Vehicle Systems (AVS), based in Harris’ Santa Ana shop. The only question left was what to call the car? Nichols himself addressed this question recently in Tom Madigan’s biography of George Follmer, “Very early in the project, Trevor and I discussed what we would call the team. Several names came up, but we wanted something that expressed the fact that the car (the Mk1) was very mysterious, and I had a rather secretive background. In fact I had worked at one time for an employer who didn’t have an address! Anyway, in part the namesake goes all the way back to the days of radio and the program, The Shadow—a show about a mystery man who fought crime and beat the bad guys. The second reason for the name came from Trevor, who is a very intellectual kind of guy. He reasoned that a shadow was two-dimensional figure. When you looked at a shadow you can measure the length and width, but the third dimension (height) is missing. With the Knee-High car it was almost a two-dimensional entity. And that’s the story.”

Shadows of Titanium

Harris and Nichols’ revolutionary Shadow MkI “Knee-High” car began testing in 1969, and due to having worked with George Follmer and mutual friend Bruce Burness on Follmer’s Lola T-70, Harris convinced Nichols to bring Follmer into the Shadow organization. While the Knee-High car is a fascinating story, in and of itself, for our purposes here it will have to suffice that a car this revolutionary was going to be plagued with problems. It took Firestone longer than anticipated to develop the smaller 10-inch front and 12-inch rear racing slicks, not delivering the first batch until late in 1969. The small wheels dictated small brake disks, which were more prone to overheating. The near prone driving position was untenable and needed to be revised, as well as a host of engine-related issues including cooling problems and issues with the Hilborn fuel injection the team first used.

While Follmer was able to post a reasonable 5th-place qualifying time at the opening Mosport round, the season quickly devolved from there, with a disappointing string of retirements. After just three races, Nichols decided to pull the plug and rethink his options.

As Shadow struggled with making its revolutionary car work in the 1970 Can-Am series, another young renegade designer was seeing his own new concept come to fruition. Peter Bryant was a British mechanic-turned-engineer who had first come to the states with John Surtees in 1963 and decided he liked the weather and would stay. By 1969, he had designed his own unique take on a Can-Am car, the Ti22, named for the chemical symbol and atomic weight of the super-lightweight metal titanium. Bryant had built a handsome Can-Am car using titanium, and had managed to bring together a team that included sponsorship and materials from the Titanium Metal Corporation of America and the services of Formula One hot shoe and Le Mans winner Jackie Oliver. While Nichols and his Shadow team struggled during the 1970 season, Bryant’s Autocoast Ti22 team showed flashes of brilliance with a surprising 2nd-place finish in the season-opening Mosport round and a pair of 2nd-place finishes, behind season champion Denny Hulme, during the final rounds at Laguna Seca and Riverside. With Oliver finishing 5th in the championship, Bryant was looking forward to building upon their success for 1971.

However, he was blindsided when he was summoned into his “partner’s” office and told that he was both summarily fired and that he, in fact, had no ownership in the team despite representations that he did. According to Bryant, “The reality that I’d lost control of ‘my’ car drove me into a deep depression that I’d never before experienced. I couldn’t come to grips with what happened. I just went into a funk…. How had this happened to me? That was the question I kept asking myself. Why had they done it? The only reason that I could come up with was money. I was the highest-paid guy on the team…if money was tight, they might cut expenses, reasoning that because they had the car, they no longer needed the designer.”

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

Fortunately for Bryant, the team’s driver, Jackie Oliver, stayed with him, as did the lucrative Goodyear relationship. Once Bryant got out of his funk, he set his mind to developing a new design for the 1971 racing season. Since movable aerodynamic devices like those seen on the Chaparrals would be banned, Bryant reasoned that the key to speed in the 1971 Can-Am would be extremely low drag. In order to attain that he needed to create a car with a much lower profile, not dissimilar to the concept tested by Harris and Nichols with the failed Knee-High car. Figuring Harris had taken the formula too far, Bryant reached out to his Goodyear contacts and asked if they would be willing to develop a smaller-sized racing tire—12 or 13 inches at the front and 15 inches at the rear. Goodyear readily agreed. With this in hand, Bryant made a short list of possible financial backers, with Don Nichols at the top of that list.

Bryant met with Nichols at his Palos Verdes Estates home and pitched him on the idea of a low-profile, Ti22-type Shadow that would utilize smaller, low profile Goodyears, though these would be bigger than the Firestones Nichols and Harris had used. According to Bryant, having learned his lesson the previous year, he also stated that he would need to have an ownership stake in the venture. After a day or two of deliberations, Nichols rang up Bryant and agreed to move ahead with what would become known as the Shadow Mk2.

Enter UOP

For the 1971 season, Bryant designed a much more “conventional” car compared to the Shadow Mk1. Bryant’s Shadow Mk2 was low and sleek-looking with a 98-inch wheelbase, 60-inch front track and 57-inch rear track. According to Bryant, “The dimension that would make the biggest difference in the performance was the overall height of the body over the rear wheels, which would reach just 24 inches. This was only attainable with the low-profile rear tires, and would make the airflow to the rear wing very effective in creating downforce.” Bryant added, “The end result was that the Shadow Mk2 looked very low and fast and, painted black, even a little sinister. This made Don Nichols very happy. He liked that sort of image.”

With primary sponsorship from Universal Oil Products, the UOP Shadow with Jackie Oliver at the wheel was ready to take on the 1971 Can-Am season. While the team missed the opening round because Oliver was racing at Le Mans, at St. Jovite Oliver qualified 4th only to have a piece of fuel tank debris clog his injectors and end his day early. The balance of the season would prove to be a succession of DNFs, despite the car showing tremendous speed, including snatching the pole at Elkhart Lake. By and large the season was plagued with engine problems, as well as issues with the new, smaller Goodyear tires and instability created by using inboard front brakes as a way of overcoming the smaller disc size necessitated by those smaller tires. All within the team agreed that while the “revolutionary” small tire concept was fast, the team needed reliability and therefore needed an even more conventional racecar.

A “Conventional” Shadow

For the 1972 Can-Am season, Bryant elected to keep basically the same monocoque chassis from the Mk2, but revise it to accommodate the regular, full-sized Can-Am wheels and tires. Additionally, Nichols told Bryant that he had plans in the works to develop a turbocharged engine—perhaps in reaction to Porsche’s announcement of its turbocharged 917/10—which meant that the new Mk3 would have to be able to accommodate nearly 100 gallons of fuel to do a full 200-mile race!

Of course, in the end, the 1972 Can-Am season would be dominated by George Follmer and the Penske-run Porsche 917/10. Oliver and the Shadow Mk3 again showed great flashes of speed, notching up a 2nd place at Mid-Ohio, a 3rd at Donnybrooke and a 4th at the season-ending Riverside round, but every other race would end in DNFs from a variety of different ailments. The Shadow Can-Am team was becoming synonymous with speed…but also unreliability.

Intrigue and Division

While at the Donnybrooke round in 1972, Bryant received a call from his wife Sally, asking if he had seen the latest issue of Competition Press. She went on to tell him that UOP had announced that it was going to sponsor Shadow’s 1973 entry into the Formula One series, but with a car designed by Tony Southgate! Crestfallen, Bryant confronted Nichols the next day. Bryant recalled, “He told me he’d intended to tell me after the Donnybrooke race…. He reiterated that he had no intention of asking me to leave the team. Suffice to say that I walked back to my room feeling terrible. It was happening again! It was just like the situation with the Ti22 team at the end of the 1970 season. I was very depressed.”

While Nichols didn’t ask Bryant to leave the team, he did completely relocate the Can-Am team from Signal Hill, California, to Chicago, Illinois (near UOP headquarters), while the F1 operation would be located near Southgate in Weedon, Lincolnshire, UK. Bryant had no interest in relocating, so he asked Nichols about his 10 percent ownership stake in the team. Bryant recalls the answer, “I asked him if he was going to issue any stock to me and he said I had no stock.” With nothing codified on paper, Bryant yet again found himself out of a team with nothing to show for it.

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

When asked recently about his decision to switch designers, Nichols commented, “Peter Bryant was a mechanic who had graduated to car designer. I know a lot of people who tell me they feel he had real talent. He was good, and the cars were clean and nice and they did well, but when it came time to have the big contract with UOP, then Tony (Southgate) was available. Tony had lots of advantages. He had a very close relationship with the Imperial College in London where they had wind tunnels. Plus, he had fresh ideas, and he was blindingly quick at designing things and designed some beautiful cars for us right away.”

Shadow Ascending

For the 1973 season, former BRM and Eagle designer Southgate’s brief was to design a car for the team’s first foray into Formula One. With high ambitions for his team—and significant sponsorship from UOP—Nichols also directed Southgate to work up a new entrant for that year’s Can-Am championship, though for this latest iteration, Southgate was directed to build a stouter, more conventional car capable of accepting the new turbocharged V8 engine that Shadow had in development.

This new car, dubbed the DN2, featured a much heavier aluminum monocoque with conventionally sized wheels, tires and outboard brakes.

With the team biting off such a big chunk that year with two, top-level programs, it is perhaps not surprising that both came to the grid somewhat late and underdeveloped. In the case of the DN2 Can-Am car, it made its debut appearance at Mosport not with its new turbocharged engine, but with the conventional fuel-injected one. As a result, Oliver qualified some eight seconds off of poleman Mark Donohue’s pace, only to DNF two laps into the race with gearbox troubles.

Despite no new engine at the next round at Road Atlanta, Oliver did qualify 4th fastest, but then DNF’d again, just 11 laps into the race, with suspension problems.

It wouldn’t be until the fifth round of the season, at Elkhart Lake, that the turbocharged car would appear, but the engine proved so fragile and temperamental that Oliver couldn’t even coax a qualifying lap out of it before having to take over teammate James Hunt’s normally aspirated DN2. When asked about his early experiences with the Shadow turbo development program, George Follmer recalls, “It was a disaster. It didn’t have good throttle control, it was either on or off. It was just so sudden and so violent, it was really hard to control.”

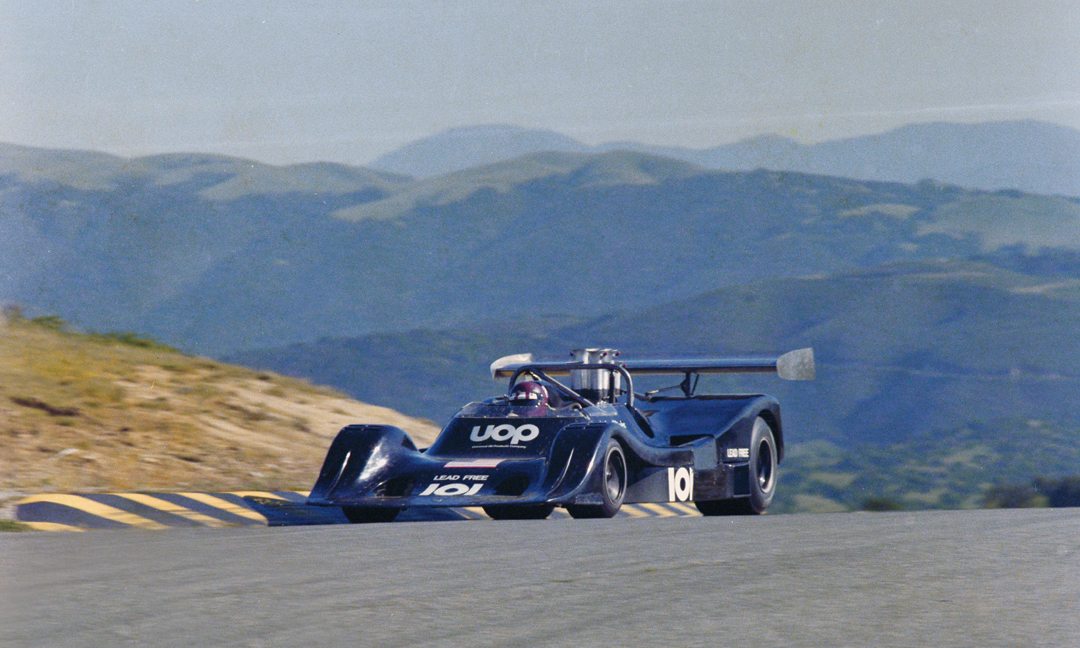

Eventually, by the last few rounds of the season, Oliver was able to notch up a 3rd at Edmonton and a 2nd at Laguna Seca, but between the now seemingly ever-present reliability problems and the juggernaut of Donohue and Penske’s Porsche blitzkrieg, this was not the season the Shadow team had hoped for.

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

It All Comes Together…Sort of

By the end of that 1973 season, two events had occurred that ultimately sealed the fate of the Can-Am. The first was Mark Donohue’s domination of the season with the 1200-hp, turbocharged Porsche 917/30. The second was the beginning of the OPEC Oil Crisis in October of that year. With gasoline being rationed in the U.S. and prices for a barrel of crude oil skyrocketing to four times its normal price, the world suddenly became very conscious of fuel economy and the impermanence of oil. As a result of both of these events, the boffins at the SCCA decided that for the 1974 Can-Am series they would create new rules—“Energy Measures” as they called them—that would include a new minimum fuel economy (3 mpg), as well as a format change that would break the usual 200-mile feature race down into two 100-milers. Penske and Porsche took one look at the new rules and realized that their 2 mpg, gas-guzzling 917/30 would be severely disadvantaged in this new format and, therefore, promptly decided to retire from the series as champions. With the very future of racing looking so uncertain, other manufacturers like McLaren and Lola also decided that this would be a good year to sit things out. Shadow, on the other hand, had UOP money in their pockets and a big chip on their shoulder. This was finally the season to get it all right.

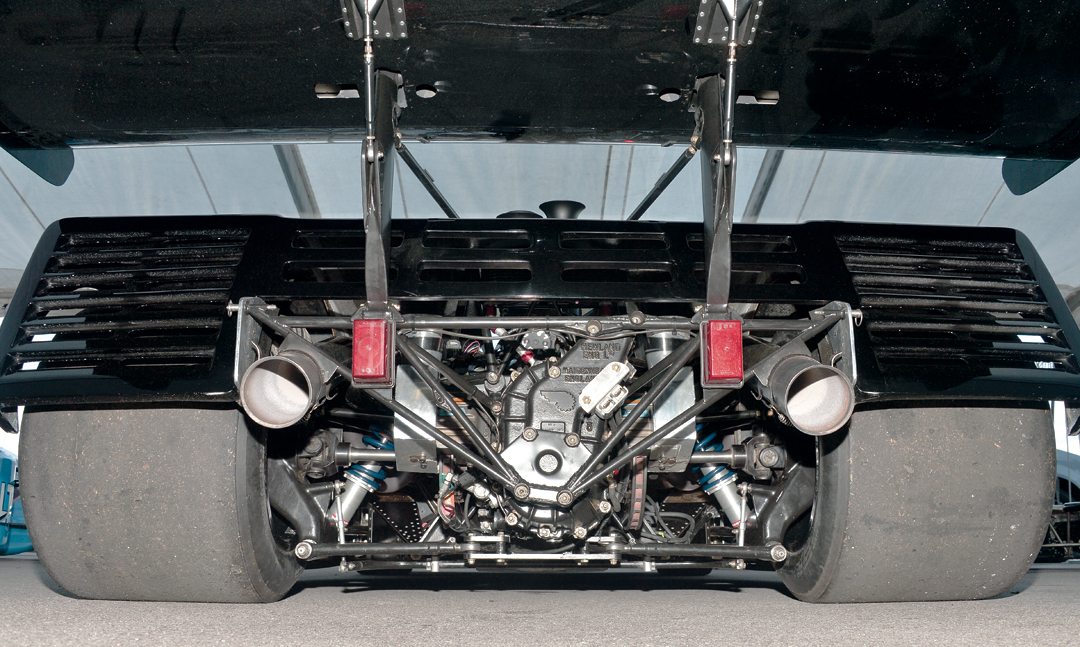

Southgate began work on the ’74 contender, the DN4, early. With the new rules requiring two heat races of only 100 laps each and a maximum fuel allowance of 37 gallons, there was no longer any need for the Shadow to carry a huge, heavy fuel load. Southgate laid out a car that was two inches longer than the DN3 (better high-speed stability), lighter and featured a lower, more aerodynamic frontal area by decreasing the front wheel diameters from 15 inches, to 13-inches. Whether due to economy, design or both, Southgate also carried over much of the suspension components from the F1 car to the new DN4, with unequal length A-arms at the front and a lower wishbone at the rear, located by two trailing radius rods and a pair of parallel lower links.

With the rules now dictating a minimum fuel economy of 3 mpg, many thought that teams would have to revert back to the smaller displacement engines seen in the early days of the series. However, Shadow’s engine master, Lee Muir, had other ideas. He stuck with the tried-and-true 495-cid Chevrolet V8, but instead focused on the precision calibration of the engine’s Lucas mechanical fuel injection unit. Muir was so successful in this regard that not only was he able to procure the required fuel economy, but he also raised the power output at the same time! While the team claimed 735 bhp from Muir’s units, it is widely held that they were making closer to 800 bhp…and this in a much lighter car!

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

During the off-season, there were more shakeups than just the rules. On the driver front, friction on the F1 team between George Follmer and Jackie Oliver saw Follmer depart and Nichols bring in 1971 Can-Am champion Peter Revson. Revson and Oliver were to team up both in F1 and the Can-Am, with the new DN4.

The new DN4 prototype (DN4-1P) was finished in early March and was immediately subjected to a rigorous pre-season testing program—reliability was not going to be an issue this year. However, Oliver and the team had to take a brief break at the end of the month to compete in the third round of the F1 championship at Kyalami, in South Africa. Sadly, during a March 22 test session, Revson’s Shadow DN3 suffered a catastrophic front suspension failure that put him hard into the Armco and he succumbed to his injuries.

Pyrrhic Victory

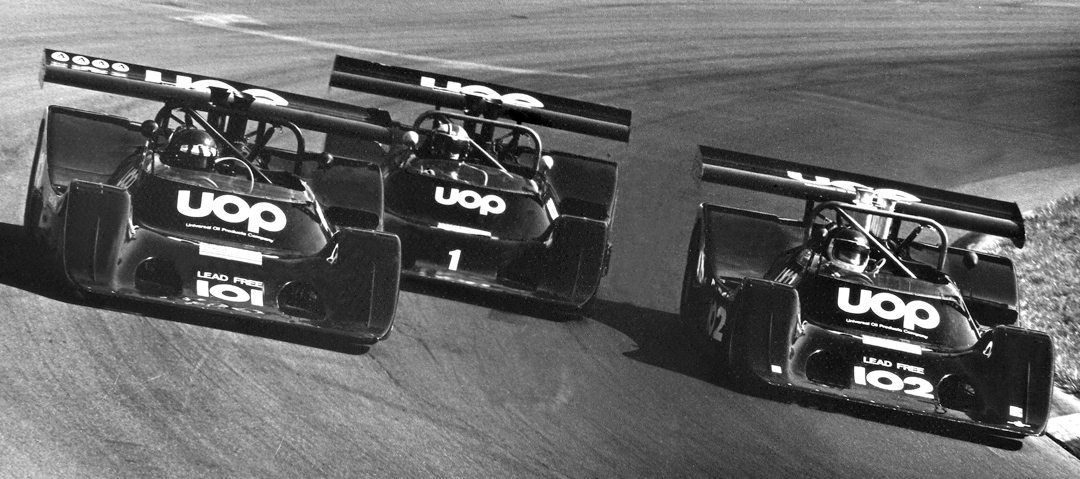

With the sudden loss of Revson, a deal was soon put in place that returned Follmer to the Shadow team to partner Oliver in the Can-Am. More than 1,800 test miles were put on the prototype chassis before it was tucked onto a trailer and sent to Mosport for the opening round on June 16.

At Mosport, Follmer took over the prototype and climbed aboard, 10 days before the race, for a test session. However, coming down the steep hill toward Moss Hairpin, the throttle stuck open and a violent crash ensued. Follmer recalls, “The crash was a result of a little seam on the tub next to where the throttle went down and when I let off the gas, it got caught up on the seam and it didn’t close the throttle. So I hit with…basically, about three-quarters of the throttle open. I ended up sideswiping the Armco, but it broke a couple of ribs and that didn’t help the season at all for me!”

The damage was comprehensive enough that the team had to strip the chassis and build up another car in time for the season opener. Chassis DN4-1P was sent back to Illinois, where it was rebuilt as a spare for later in the season.

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

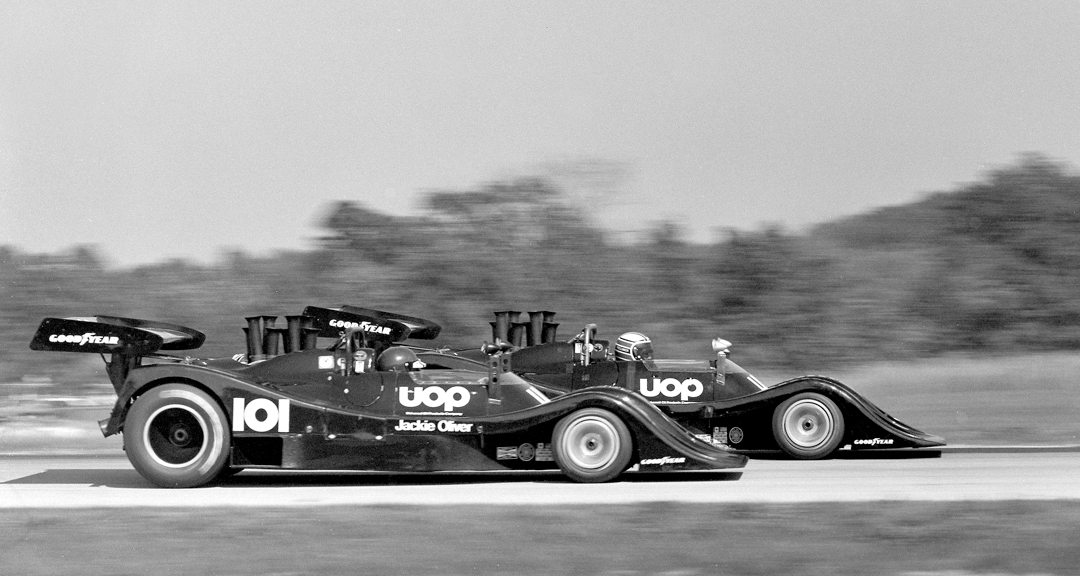

On race day, Oliver claimed the pole with Follmer in his just finished DN4 a mere second off. In the first heat, the antagonistic duo took off for the first turn, with Follmer diving up the inside and barging his way through—clearly, no love lost and no quarter given. Follmer would go on to claim victory in that heat, despite the fact that he was having to drive with a Lidocaine spinal block in order to control the pain from his broken ribs! But Machiavelli’s long shadow soon cast itself again over the team.

While sitting on the pole for the final heat, Follmer was in for a jab of pain not generated by his aching ribs. “So, I’m sitting on the grid,” recalls Follmer, “and Don came up and told me I had to let Oliver win.” When asked recently why he agreed to return to the Shadow Can-Am program, after having such a difficult experience the previous year in F1, Follmer replied, “I was coming back as a teammate to Oliver, but I wasn’t told that I had to let Oliver win. I knew I could beat Oliver, but they were going to give Oliver that championship whether he earned it or not. I’m going to be really blunt…Jackie was not a teammate. As far as he was concerned it was always Jackie. Jackie was a good race driver…he just had a little, shitty attitude.”

Whether pre-ordained as Follmer describes, or perhaps a response to the possibility of his two drivers taking each other out of the championship, Oliver did indeed go on to the overall victory at Mosport, over Follmer. But what of the other teams? With no factory efforts other than the Shadows, the rest of the field was made up entirely of independents running older machinery, so—good, bad or indifferent—the 1974 season would become the “George and Ollie Show.” With fewer competitors in old equipment and a global oil crisis, however, race organizers began abandoning their Can-Am dates for fear of financial disaster. Of the eight races announced for the 1974 season, only five would end up being run.

At Road Atlanta, Oliver would win with Follmer 2nd, while the results would be the same at Watkins Glen 14 days later, on July 14. At Mid-Ohio, the Shadow duo was in for a shock when Brian Redman turned up with Penske’s Porsche 917/30 and put it on the pole. Of all the tracks that the 917/30 ran, Mid-Ohio was the one that yielded the best fuel economy, so the Penske team felt they had a solid chance there. In the final, both Shadows managed to get by Redman, only to battle each other to the point that they made contact and Follmer spun off. Follmer made his way back to the pits, but got out of his car and stormed off(!), leaving Oliver to win and Redman to finish 2nd.

At Elkhart Lake on August 25, the Shadows once again dominated the front row with Follmer on the pole. In the first race, Follmer led until he eventually let Oliver by for the victory and then in Sunday’s final, Follmer had a halfshaft break on the opening lap, while Oliver’s engine uncharacteristically blew up with just four laps to go, handing the victory to Scooter Patrick in his McLaren M20. Perhaps it should have come as no surprise that the day after Elkhart Lake, the SCCA announced that the season’s final race at Riverside was to be cancelled, thus annointing Jackie Oliver that year’s—and ultimately the final—Can-Am champion. After many years and much intrigue, Don Nichols finally had his Can-Am championship, albeit in a somewhat anemic series that was suffering from both mismanagement and world events.

On winning the ’74 championship Nichols commented, “I think that was a great experience. The fuel capacity rule change didn’t suit Porsche, and Brian Redman drove Penske’s 917/30 at Mid-Ohio and got pole position, but he didn’t win the race, Jackie Oliver won it for us. What I really wanted was a championship, and it was much more difficult than Formula One.”

With the season prematurely cut short, Nichols had concerns about sponsor UOP not getting sufficient publicity from the team’s success. As a way of maximizing their exposure, he arranged for a pair of All-Shadow match races—or rather “grudge races” to be held. The first was a 15-lapper held prior to the USGP at Watkins Glen, the first week of October. Three DN4s were turned out for Follmer, Oliver and F1 driver Jean-Pierre Jarier. Based on contemporary reports from the event, it looks likely that the rebuilt prototype chassis was one of the three cars used, though it is unknown who drove which car in the race. What is known is that Follmer won, with Oliver 2nd and Jarier 3rd. A week later at the Laguna Seca F5000 round, Jarier and James Hunt fielded Shadow DN3 F1 cars, against the DN4 Can-Am machines of Oliver and Follmer. There it was no contest, as the nimbler F1 machines ran circles around the Can-Am cars on Laguna’s twisty circuit, with Jarier easily winning over Hunt, followed by Follmer.

From Follmer’s perspective, he ranks the Shadow DN4 as one of the very best all-around Can-Am cars, “It was a good car. It was a really good car. It was fast, it was nice to drive, it stopped well, it had good adhesion off the corners, it was predictable. In fact, I was actually faster than Mark’s (Donohue) 917/30 in a lot of cases. I think the Shadow was a better car than the Porsche…still one of the best I ever sat in.”

Driving the Shadow

I’m not proud of it, but I’m going to have to come clean, right from the start, and declare that the prospect of test-driving the Shadow DN4 scared the shit out of me. So much so in fact, that I found myself looking for convenient excuses why I couldn’t travel to Brian Redman’s Targa 66 event in Florida to drive the car. In the past, I’ve driven cars with more horsepower—the Eagle-Toyota GTP (VR, April 2007) had over 1,000 on full boost—but never anything with that much torque (800-lbs-ft!) available right at the crack of the throttle! Between the thought of pressing the throttle and having the car side-step into a wall and images of Follmer smacking the Armco with a stuck throttle, I was more than a little apprehensive as I pulled into Palm Beach International Raceway this past February to have my crack at this beast.

As a result of Follmer’s crash at Mosport, Chassis DN4-1P was rebuilt and served as a backup car later in the season at Elkhart Lake, as well as presumably the third chassis for the Watkins Glen “grudge race.” After the two exhibition races in October, DN4-1P went back to Nichols’ shop in Salinas, California, where it sat covered up for the next 26 years. Then, in 2000, the car was restored and sold to Andrew Simpson of Texas, who campaigned it in vintage races for the next seven years before he sold it to Rudy Junco of Monterey, Mexico. Junco raced the car off and on until 2012, when he sold the Shadow to its current owner James Bartel. With the help of his son-in-law Craig Bennett at RM Motorsports, the Shadow has been meticulously prepared and raced since then, and has won the SVRA class championship in both 2013 and 2014.

I circled the Shadow warily for some time—never taking my eyes off it for fear it might bite me even in the paddock! When the time finally came to get ready, Craig Bennett asked me if I thought I’d need the seat changed out. “Nah, you’d be amazed at the cockpits I’ve been able to squeeze myself into,” was my cavalier reply, hoping that my voice wouldn’t quiver and give away my false bravado.

Photo: Dan R. Boyd

I stepped over the massively wide sills of the Shadow and then proceeded to lower myself into Bennett’s custom seat when I felt a sharp pain on either side of my butt…damn, it was already trying to hurt me! No, instead I learned that no matter what I thought, there was no way my birthing hips were going to smash down into the jockey-like Bennett’s seat! Once everyone realized the same, there was a momentary look of panic from Bennett’s crew, when they realized the amount of work required to prepare a makeshift seat for me and get everything changed over.

“Just pull the seat out and I’ll sit in the bare tub,” was my response to their anxious looks. With a look of pure relief, they pulled the seat out and we were all pleasantly surprised that I now fit well in the cockpit, could just cinch up the straps and had the perfect amount of leg room for my freakishly long legs. The bad news, however, was that I had just given up my last viable excuse…I was past the point of no return.

Now well ensconced in the cockpit, I first flick on the ignition switch, then the mechanical fuel pump, look for the thumbs up from the guy with the battery jumper and then, with a lump in my throat, I crack the throttle open and push in the black rubber-covered starter button…and that’s when all hell broke loose. No words can ever adequately describe the explosion of sound that comes from a fuel-injected Big Block V8 attempting to vaporize the planet from six inches behind your head. It is at once the most ferocious, startling and addictive aural bombardment you will ever experience in the automotive world…ever. BLAT!-BLAT!-BLAT! It was like each poke of the throttle was directly wired to my adrenal glands, forcing me to poke it again for another dose of adrenalin.

With the car warmed up, the excuses put away and the track now open, I firmly dip the clutch, pull back and down on the Hewland 5-speed gearbox and somewhere, back behind all those thermonuclear detonations, I feel something go “clunk” as first gear is selected. Here it comes—with a paddock full of clearly envious onlookers wondering who the wanker in the Shadow was—I feed in some throttle, release the clutch and pray I don’t suffer the ignominy of stalling it right there for all to see—whew!—like the most docile little production car, the Shadow smoothly pulls away and out into the pit lane.

My first few laps in the Shadow were spent behind our camera car, so I was afforded the opportunity to settle in and get a feel for the car, before things got “real.” Sitting down low, inside the wide “two-seat” cockpit gives the sensation that the car is huge and wide. Looking through the wide windscreen I can see the two large black bulges either side that cover the front wheels, while looking in the rear view mirrors I see what looks like 10-yards of black fiberglass on either side. From inside the car, it looks deceivingly massive, while from outside it seems much less so.

With our photography done, it was finally time to wrestle my demons. I pull onto Palm Beach’s front straight, get her straightened out, take a deep breath and, from second gear, progressively squeeze on the throttle. The sudden burst of acceleration is nothing short of staggering. Simultaneously, I have both the sensation of my eyeballs being squeezed back in my skull as well as a deep, violent vibration pulsating through my chest as all 495 cubic inches behind me unite in their effort to terminate my existence. Of course, this whole experience only lasts for a second or two, before I lift, and with a very firm hand, slam the big Hewland into third and “progressively” bury my right foot again…more eye squishing and chest collapsing then ensue.

As the Turn 1-2 chicane approaches, I get hard on the brakes, dip the clutch, blip the throttle and forcefully downshift into second. I say forcefully, because the big Hewland gearboxes in these Can-Am cars do not tolerate mamby-pamby shifting. You may think you are trying to be easy on it, but if you try to downshift these delicately, you will only be rewarded with horrible sounds from the back…and no gears selected in the process. As counterintuitive as it may seem, the faster and harder you shift them, the better they like it…yet another example of what contrary beasts these cars can be to drive.

Exiting the right-hand Turn 2 in second, I’m able to accelerate through Turn 3 and fade to the outside to line myself up for the long, decreasing-radius Turn 4. This turn would be a challenge for me all session. It was difficult to know how much speed could “safely” be carried into it, it was hard to see the apex on the off-side of the car and, because I was strapped into the tub and not a seat, the g-forces were throwing me to the side of the cockpit and impairing my line of sight! For the first few laps, this was so disorienting that I just left the Shadow in third gear and kind of luffed my way through. Amazingly, the car has so much torque, that even though I was basically on idle in third at the exit, all I had to do was bury my right foot and the car would instantly leap to Mach speed without an iota of hesitation. Just stunning.

Accelerating hard out of Turn 5, I get another brief burst of that morphine-like acceleration before it is hard on the binders for the right-hand Turn 6, then a quick flick left and then right again through Turns 7 and 8. Despite the car’s perceived size and brutishness, it is amazingly nimble and predictable as I “Flick and Squirt” through this series of turns that open up onto Palm Beach’s loooong back straight.

As I accelerate out onto the back straight, I now work up the confidence to really put my boot in it. WAAH!-shift-WAAAAH!-shift-WAAAAAAH!-shift. I’m already into the Shadow’s fifth gear and I’m only about halfway down the straight! Keeping my foot in it, I see almost 7,000 rpm (and God) before the braking markers indicate I need to slow down or follow in Follmer’s uncomfortable footsteps. Getting hard on the brakes at that speed causes the Shadow to shimmy back and forth a little, but it quickly settles and then I can forcefully make my way down through the gears for the long decreasing-radius Turns 9 and 10 that lead back onto the front straight.

With each subsequent lap, I was able to push the Shadow a bit more and start to experiment with using more of the gearbox. The rewards for this experimentation were a very stable and predictable car that would just launch out of turns with ferocious force. The car felt so predictable and progressive—and the acceleration and speed were so intoxicating—that after a few more laps I realized I was starting to tread on dangerous terrain. This is when a Can-Am car will bite you, not when you’re scared shitless, but when you think you’ve got it all figured out. I raised my hand and made my way back down the pit lane. I pulled in and shut the Shadow down with one last, gratifying blast of the throttle, as the crew quickly swarmed around. “What’s wrong? What happened?” were the concerned questions from the crew on why I came in before the session was over.

“It’s perfect, quite frankly,” was my response. “I think if I stayed out there any longer, we all might regret it!”

The story of the Shadow DN4—arguably one of the greatest Can-Am cars ever built—is a convoluted one that interweaves the hopes and aspirations of three designers and two drivers, with internal politics (the SCCA), external politics (the OPEC Oil Crisis) and the machinations of one enigmatic owner, all under the very long shadow of one Niccolo’ Machiavelli.

SPECIFICATIONS

Chassis:Aluminum Monocoque

Wheelbase:105 inches

Length:179 inches

Width:79 inches

Front Track:59.35 inches

Rear Track:62.00 inches

Weight: 1780 pounds – with fuel

Front Suspension: double wishbones, coilover shock absorbers, anti-roll bar

Rear Suspension: Twin lower links, single upper link, coilover shock absorbers, anti-roll bar

Engine:Chevrolet 90-degree pushrod V8

Bore x Stroke:4.5 inches x 4.0 inches

Compression Ratio: 13.2:1

Induction: Lucas Mechanical Metered Fuel Injection

Power:940 bhp

Torque: 780 lbs-ft

Transmission:Hewland LG500 4-speed

Wheels: 13 x 11 front / 15 x 18 rear

Tires: 10x20x13 front / 16.2x26x15 rear

Resources / Acknowledgements

Bryant, Peter, Can-Am Challenger, David Bull, 2007, ISBN 978-1-893618-86-2

Lyons, Pete, Can-Am, MBI, 1995, ISBN 0-7603-0017-8

Lyons, Pete, Can-Am: Photo History, MBI, 1999, ISBN 0-7603-0806-3

Lyons, Pete, Harholdt, Peter, Can-Am Cars in Detail, David Bull, 2010, ISBN 978-1-935007-11-1

Madigan,Tom, Follmer: American Wheelman, ejje Publishing, 2013, ISBN 13-978-0-9828999-2-2

The author would like to thank owner James Bartel, Craig Bennett and the staff of RM Motorsport for all their help and generosity in making this test drive possible. Additional thanks go to George Follmer, Gordon Kirby and Pete Lyons for their help, input and recollections of the 1974 Can-Am season and a special thank you to photographer Dan R. Boyd, both for his excellent track shots and period photography.