Luigi Bazzi Biography

He was called the soul of Ferrari. He had been there from the beginning and Enzo Ferrari recalled his trusted friend as “the founding member of the old guard of collaborators. Working at Ferrari till he was over eighty when health finally forced him to leave Ferrari’s side. Due to his quiet and unassuming nature to those on the outside he had the appearance of a mechanic or test driver but those with a better knowledge of the inner workings at Ferrari knew that no engine ever left the racing factory without having come under his watchful eye.

It is estimated that while working with Ferrari he had a hand in over 160 different engines in multiple configurations including his famous Bimotore that had two in a single car! No degree or diploma could fully convey his knowledge of what makes a racing engine “go” that instead was based on many years of experience first at Fiat then Alfa and finally at Ferrari.

He was born in Novara in the Piedmont region of northwest Italy on the 13th of October, 1892. Bazzi attended the Professional School of Arts and Crafts for carpenters and mechanics, which later became the Technical Industrial Institute Omar in 1933. After his studies he decided to move to Turin to work at car maker Società Torinese Automobili Rapid, also known as S.T.A.R. or just Rapid. He followed that with stints at Officine Savigliano a major industrial concern and Michelin before finally landing at Fiat.

In reviewing Bazzi’s biography it’s important to understand that the Piedmont area was the center of industry in Italy. A combination Silicon Valley and Detroit of the 40s and 50s. For a young person with Bazzi’s mechanical aptitude there would always be work available sometimes working in private industry, sometimes working through a consultancy and sometimes on a government contract. If the opportunity presented itself the ambitious would do all three. Bazzi seems to have been rather restless in his early years, that is until racing took hold. His daughter would later remark that for her father there was not much else besides the family and the workshop, and not always in that order.

He arrived as the Alfa P1 was being completed and when it proved to be unsuccessful Bazzi knew just the man and suggested that Alfa hire another Fiat engineer Vittorio Jano to develop the car. Testing the new Alfa Ascari was struck by the new cars potential and begged Jano and Bazzi to complete the car as early as possible. On the P2’s debut at Circuit of Cremona Bazzi volunteered to serve as the riding mechanic to Ascari, so eager was Bazzi to get his revenge over Fornaca and Fiat.

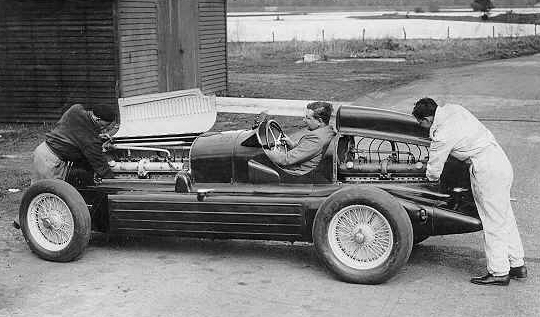

He remained with Alfa Romeo throughout the 1920s and 1930s, his most famous design being the twin-engined “bimotore” which Scuderia Ferrari built in 1934 using Alfa Romeo parts in an effort to compete with the German manufacturers. The cars were raced by Tazio Nuvolari and Louis Chiron but were too heavy and used tyres too quickly and so one was used to set a new class land speed record. In the late 1930s Bazzi was head of Alfa Romeo’s experimental department. While Bazzi is justly famous for the Bimotore he also played a large part in the design of the Alfa Romeo 158 as the overall technical director supervising Gioacchino Colombo and the rest of the design staff. It was he that specified an eight cylinder engine with a relatively small bore so as to keep the engine of a manageable length with the crankcase cast of ultra-light magnesium. The Alfetta would prove itself just before and after the war winning the first Formula 1 World Championship in 1950 and again in 1951 with the updated 159 Alfetta.

When Enzo Ferrari split with the company Bazzi would join Ferrari in short order to become head of his engine department. Bazzi once again along with Colombo worked on the construction of the first Ferrari racing car – the 125 – after World War II and when this was not a great success he reworked the engine for the new 159. Bazzi had a habit of testing the cars himself but on this occasion he crashed the prototype and broke his leg.

Ferrari would often tell the story of the 1931 Grand Prix of Monaco. Achille Varzi was up in arms regarding his seat height in his car. Remarking that two cushions were too low and three would invariably be too high. Bazzi told Varzi to go get some coffee and that he would sort things out. While Varzi was gone Bazzi grabbed the newspaper that Ferrari was holding and placed it between the cushions. Ferrari remarked that the newspaper could not have made more than a 1/16 of an inch of difference. Varzi returned and once seated in his car announced that the height was now perfect. He was Enzo Ferrari’s closest associate and stayed with the company until his retirement in the early 1960s. He continued to be an advisor to Ferrari until his death in 1986, at the age of 93.

“Carla dearest, among much unanimous regret I receive word of his passing and it’s difficult to summarize who he was , Luigi for myself and for Ferrari. Without him, neither I nor the house that bears my name would represent what today we are attributed. Remember the children and grandchildren with the best wishes of all good.”

This Enzo Ferrari wrote when my father died. Also sent money to the Industrial Technical Institute Omar in Novara, where my father had studied, to establish a scholarship in his memory. Ferrari was a very generous man, who remembered the people in all circumstances significant.

(Reconstruction performed by Nunzia Manicardi based on an interview with his daughter Ms Carla Bazzi, in 1998)