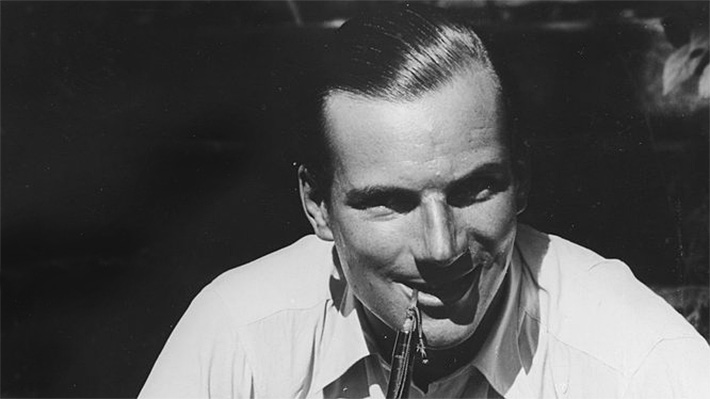

Richard Seaman Biography

Born on 4 February 1913 to wealthy parents, Seaman fell in love with cars as a schoolboy. He would spend endless hours drawing pictures of racecars including a Seaman Special. As soon as he was old enough to get a license his parents bought him a Riley sports car and later replaced it with a MG Magna. Seaman was enrolled in Cambridge at this time but his heart was in cars. He entered several local races with minimum success. In 1934 he returned from school and announced to his distressed parents that he would not be going back. Instead he was joining Whitney Straight and his racing team. He purchased Straight’s MG Magnette and set off for the continent making his debut in the GP de L’Albigeois where he promptly stalled on the grid. The next race was a Voiturette event, which preceded the Coppa Acerbo. On that difficult 36-km circuit he finished a commendable 3rd place. His first victory came in a support race leading up to the Swiss Grand Prix where he started from the ninth row of the grid to take the lead on the 11th of 14 laps. His victory was marred by the death of his teammate Hugh Hamilton.

His debut race was in Tripoli where he lay 2nd to Lang prior to suffering supercharger trouble which dropped him to seventh. Seaman became a popular member of the team because of his honest, straightforward character. Neubauer took a strong liking to the young driver. Seaman’s first year with Mercedes was solid if not spectacular. The mechanics were impressed with his mechanical knowledge, which he relayed through Rudolf Uhlenhaut, who spoke fluent English. 1938 marked the beginning of the new 3-liter formula and because he was still the junior driver on the team a new car was not ready for him until the German Grand Prix in July. During his forced “holiday” he met his future wife Erica Popp whose father was President and co-Founder of BMW. Seaman’s mother was at first friendly to the young German girl until she found out that her son intended to marry this girl. She was violently opposed to the marriage, more for the problems she felt that her son would encounter for marrying a very young German girl than for any personal animosity she had towards her. Sadly Seaman became estranged towards his mother until his death.

The next race that he drove in was the Swiss GP where he came in a fine second to Caracciola. After another successful season that saw him win his first race he was re-signed for the 1939 season. At the opening race he had to stand down, as there were only two new cars ready. The next race, the Eifel GP ended seconds after it began for Seaman when he suffered a failed clutch. Going to Spa in Belgium, Seaman was determined more than ever that he should no longer be considered a junior or reserve driver. The race was run in a downpour and on lap nine even the regenmeister Caracciola spun. On the tenth lap Seaman took the lead while the rain had stopped. With the track both wet and dry at various places experience would have told the driver that this condition could be the most dangerous. Seaman could only think of the first two races of the year and was out to prove that he was second to none on this or any other team. At La Source Seaman’s car went into a skid and left the track, crashing sideways into a tree. The driver’s compartment had been damaged and as the car burst into flames the driver was trapped. Two Belgian officers pulled the driver clear but he was to die from his burns just after midnight. Neubauer would relate in his memoirs that it was a familiar story:

Ninety-nine times a driver takes a bend at precisely the same angle and precisely the same speed. Then the hundredth time he wants to go one better, to cut one second off his time and puts a shade more pressure on the accelerator. That shade is fatal.

At his funeral were representatives of both Mercedes and Auto Union and the board of directors at Mercedes decreed that in all of the display windows of their dealerships would be placed a portrait of the only driver ever to be killed driving one of the Silver Arrows.