Motor Racing History – The Pre-War Grand Prix Period

Formula Libre

Grand Prix racing in accordance with a strict formula based on engine size and weight was abandoned in 1928.In its place, races were run under Formula Libre rules. In lieu of the major manufacturers, drivers raced as privateers or in partnership with specialist racing-car builders such as Alfa Romeo, Maserati and Bugatti dominated racing during this period in the hands of drivers such as Louis Chiron. In 1929 William Grover Williams won the first Monaco Grand Prix driving a Bugatti. The Bugatti race cars were some of the most beautiful cars ever built but suffered from inadequate brakes.

A famous quote attributed to Ettore Bugatti after criticism of his brakes was:

“I build my cars to go, not stop”.

In 1930 Alfa Romeo decided to enlist a new company to direct all of their racing efforts. This company was called Scuderia Ferrari and was run by Enzo Ferrari.

One event that stood out during this period was the Mille Miglia . The Mille Miglia was designed as a way to promote and improve Italian motor car design and reliability. Improving Italian roads was unfortunately not a priority as a recent visit to that country can attest. The Mille Miglia provided a test of almost 1000 grueling miles of good, bad, and indifferent roads. The route traveled east to Vicenza, south along the Adriatic to Pescara, west to Rome and then northwest to Brescia.

It was the province of Italian drivers for most of its history. Traditionally the first cars, the amateurs, would leave Brescia at 9 p.m. at 1-minute intervals and return 16-24 hours later. Due to the amount of entrants the works teams would depart sometime the next morning. Each car would have its starting time painted on the car, which would allow spectators some indication of their relative placement. Hundreds of thousand of spectators would line the roads to cheer their heroes on. In fact it was a lack of crowd control that would actually cause this race to be abandoned after the 1957 race which saw the death of the Marquis de Portago, his co-driver and ten spectators. This race has played host to many epic drives such as that undertaken by Caracciola in 1931 and Moss/Jenkinson in 1955. But none could top the Mille Miglia of 1930 when Nuvolari racing through the night, passed Varzi with his headlights turned off! In three weeks Varzi returned the favor by coming back from a car fire to win the Targa Florio.

The 1927 season was dominated by the French Delage team which won the Spanish, Italian, French and British Grands Prix. The works team was duly crowned European champion. At one point the car, driven by Benoist (who also won the European driver’s championship), completed over 1,400 miles in competition with — it is claimed — never having to raise its hood.

Another car from France would come to dominate the racing scene from 1927 to 1931. The Blue cars from Bugatti, specifically the Type 35 would prove to be one of the most successful cars in history. Their fine workmanship and the ability to be competitive “right out of the box” provided for their appeal. The French driver Rene Dreyfus stated that “You could place the car wherever you wanted, the road holding was fantastic…the precision of the steering was something fantastic”. InIn total about 400 Type 35s were built and raced by a legion of drivers from raw amateurs to established stars such as Dreyfus, 1929 Monaco GP winner William Grover Williams and Louis Chiron.

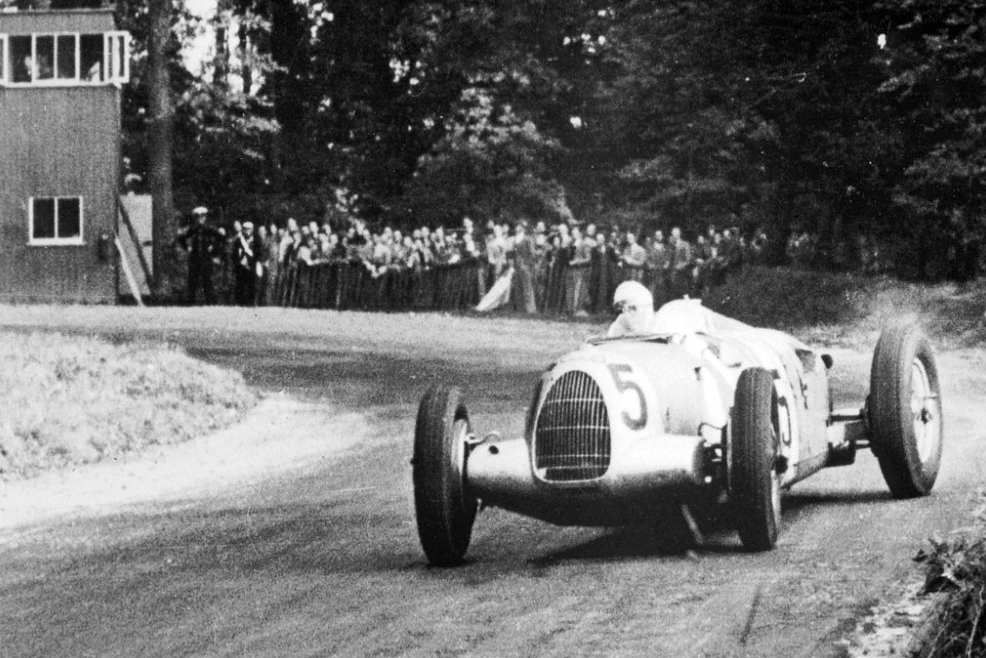

The Silver Arrows

In 1934 the Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus (AIACR) announced a new formula. The formula that limited the car minus driver, fuel and oil to 750kg without restricting engine size. The race length of a Grand Prix was a minimum 500 kilometer. Hitler’s Germany sponsored two teams to compete under this new formula, Mercedes and Auto Union. Each firm split an annual grant of 450,000 Reichmarks with additional bonuses for certain results.This money would only cover a small portion of the vast sums required. It has been estimated that Mercedes needed an annual amount of approximately four million Reichmarks to support their motor racing. In Alfred Neubauer, the team manager, they had just the right person who knew how to spend their money!

It was commonly thought that a 2 litre engine was all that could be fitted into a proper race car under those restrictions but due to the use of new light materials the German cars had engines of over 4 liters. Both teams built brand new cars that were the fastest race cars yet built. This the result of the new formula that had been meant to lower speeds! Mercedes’ chief designer, Dr. Hans Nibel, designed a car around a conventional layout but incorporating some of the latest development in racing technology.

Auto Union a amalgamation of four firms – Horch, Audi, Wanderer and DKW – chose a more radical concept for their Type A Grand Prix car. Designed by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche, the mid-engined car placed the driver lower and further towards the front. It had a V16 4.4-litre supercharged engine that ran on special fuels mixed to a very secret formulae. The exhaust fumes that poured out by the engines was so strong that bystanders would complain of nausea and headaches! The Auto Union like the Mercedes used 4-wheel independent suspension. The suspension was later changed to a De Dion system in the Mercedes to improve handling over bumps and high-speed corners. Both cars were expected to make their debut at Avus near Berlin. During practice the Mercedes all suffered from carburetor problems and were forced to pull out.

A parade of the three Auto Union race cars before 200,000 German spectators proved to be the highlight for the German team as only one car was left to finish third behind the Alfas of Guy Moll and Chiron! Two weeks later the German cars tasted their first blood. The Eifelrennen held at the Nurburgring, saw the German cars finished 1-2 with the Mercedes of von Brauchitsch leading the Auto Union of Stuck. Prior to the beginning of the race the Mercedes team created a little excitement when it was found that their cars were 1 kg over the weight limit. Legend has it that following a suggestion by von Brauchitsch, Alfred Neubauer had the paint from each car removed in order to meet the weight limit (Since the race was run to formula libre rules this appears to be a myth), leaving the polished aluminum of the cars exposed and so began the era of the Silver Arrows. The German cars were beginning to gain their stride.

Rudolf Caracciola would go on to win the title again in 1937 and 1938 while Bernd Rosemeyer would triumph in 1936. The German cars dominated Grand Prix Racing and except for remarkable victories by great drivers such as Chiron and Nuvolari the Italian and French cars had to console themselves with the 1.5-liter voiturette class. One such victory was the German Grand Prix of 1935.

Before an estimated crowd of 300,000 fanatical German fans, Nazi officials and Adolf Hitler the German Grand Prix of 1935 was held. The Mercedes team consisted of Fagioli, von Brauchitsch and Caracciola while Auto Union had Stuck, Rosemeyer, and Varzi.

The Greatest Victory of all time

By the 10th lap Nuvolari had forced himself back into the lead. A round of pitstops ensued and Nuvolari found himself relegated to sixth place. Driving like a man possessed he passed first Fagioli, then Rosemeyer and Caracciola, and finally Stuck. Going into the last lap he was still 30 seconds behind the leader von Brauchitsch and all seemed lost yet never did Nuvolari slow down. Von Brauchitsch aware of Nuvolari’s progress through the ranks from his pit crew drove his car at the limit and in so doing destroyed his tires. One let go a half lap from the finish and Nuvolari streaked to victory. “At first there was deathly silence,” MotorSport reported, “and then the innate sportsmanship of the Germans triumphed over their astonishment. Nuvolari was given a wonderful reception.” This admiration for a great champion was not shared by the representatives of the Third Reich. Korpsführer Hühnlein angrily tore up his victory speech as Nuvolari was crowned victor. The Italian flag was hoisted after much searching and to add salt to the Nazi’s wound Nuvolari produced a record of the Italian anthem that he had brought with him for good luck. The Korpsführer was not amused. This scene would be repeated a year later when another underdog by the name of Jessie Owens would make history.

In 1937 Mercedes created a W125 along with a reworked W25, both of them producing nearly 600 bhp, top speeds reaching 200mph and wheel spin in every gear. The performance of the W125 was unmatched by any other manufacturer, in fact it would not be until the Can-Am cars of the late 1960s that another race car would equal the horsepower of the 1937 Mercedes Grand Prix car.

Hermann Lang’s victory driving a Mercedes at an average speed of 162.61 mph was not bested until A.J. Foyt averaged 164.173, while winning the Indianapolis 500 in 1967. As a final exclamation point to these great machines, on January 28, Rudolf Caracciola set a new class record in a 12-cylinder car with special enclosed streamlined body. It set a top speed of 436.9 km/h during a one-kilometer run in one direction with a flying start. This is the highest speed ever driven on an ordinary road.

Tragically, before the beginning of the 1938 season, the heart of the Auto Union team was torn out by the death of its star. Bernd Rosemeyer died while attempting a speed record on the Frankfurt-Darmstadt autobahn. The Auto Union team even with the talents of Nuvolari was never the same again. The AIACR instituted a new formulae which limited engine size to 3 liters supercharged or 4.5 liters unsupercharged. Mercedes and Auto Union answered this new challenge without pause and continued their dominance. Alfa Romeo abandoned the formula and concentrated on the 1.5-litre voiturette class for their entry in the Tripoli Grand Prix of 1939. Unbeknownst to Alfa, Mercedes secretly prepared two 1.5-litre W165 cars for Herman Lang and Caracciola and promptly finished 1-2. Only the outbreak of the Second World War would stop the German juggernaut. The cars of this era have rightly been considered some of the greatest racing cars ever produced by man.