City to City Motor Races

It began with demonstration runs such as one that took place on the 22nd of July, 1894 in front of a fascinated public for these strange carriages that drove themselves or at least seemed to. The trail as it was called would cover the distance from Paris to Rouen and was organized by the journalist Pierre Giffard of Le Petit Journal; a judging-panel decided on the winner. The paper promoted it as ‘Le Petit Journal’ Competition for Horseless Carriages (Le Petit Journal Concours des Voitures sans Chevaux) that were not dangerous, easy to drive, and cheap during the journey, the main prize being for the competitor whose car comes closest to the ideal. The announcement in Le Petit Journal on 19 December 1893 expressly denied that it would be a race – ce ne sera pas une course. The easy to drive clause effectively precluded from the prizes any vehicles needing a traveling mechanic or technical assistant such as a stoker.

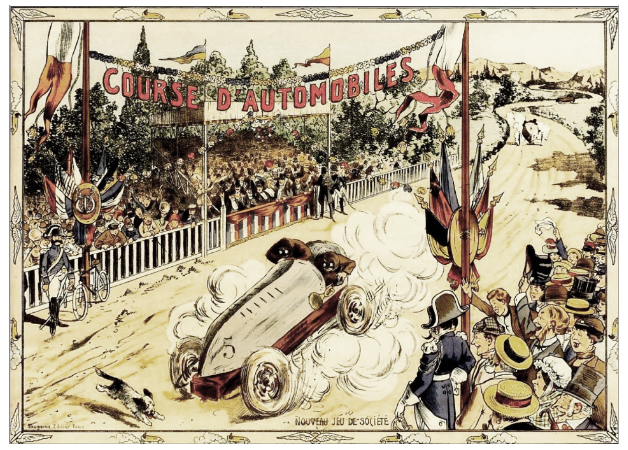

While the event drew huge crowds the organizers soon realized that the criteria for judging a winner was lost upon the spectators who would show up to watch what for them was a spectacle. Something else needed top be done to allow a manufacturer to promote the superiority of their product for inventions were all well and good but this was no scientific exercise, cars needed to be sold. The obvious solution was something that was denied at Paris-Rouen, a race and with the victory goes the spoils. Reliability was what the manufacturers were after but the public would crave speed.

Paris-Bordeaux-Paris (June 11-13, 1895)

The Comte Albert de Dion led a group of organizers for a motor race between Paris and Bordeaux before returning to Paris, a distance of 732 miles. Regulations for the event stipulated a pure race where the winner was the first car home, seating more than two passengers. Drivers could be changed during the race and repairs were allowed only with materials carried on the car, supervised by “Commissaires”. Manufacturers were prohibited to enter several identical cars so as not to “swamp” the smaller amongst them but were allowed an unlimited number of cars if they were deemed sufficiently different.

Twenty-three vehicles took of from Versailles, amongst this group were steamers from de Dion, Serpollet and Bollées and petrol cars from Benz, Peugeot, Panhard et Levassor and an electric car from the famous carriage maker Jeantaud. The face was a triumph for Émile Levassor who arrived first after completing the 1,178 km in 48 hours, nearly six hours ahead of the runner-up and at a stout average speed of 15 miles per hour. However, the official winner was Paul Koechlin, who arrived third in his Peugeot, exactly 11 hours slower than Levassor, but officially the race had been for four-seater cars, whereas Levassor and the runner-up drove two-seater cars. However as witnessed by the statue later erected at Porte Maillot in his honor it was Levassor who gained glory from the crowd.

Nine out of twenty-three cars finished the race, eight of them petrol. The sole steamer was the Bollée which was built in 1880 and carried seven passengers. One car that finished, but outside of the 100 hour window was entered by the Michelin brothers and had pneumatic tires. The car they wee driving was called the Lightning, not because of its speed but rather due to an issue with it’s steering mechanism its trajectory followed the zigzag outline of a lightning bolt.

Automobile Club de France (November 12, 1895)

The genesis for the creation of the Automobil’Club – as the founders originally called the ACF – was a historic lunch in late 1895 at Jules-Albert de Dion’s residence with Baron de Zuylen and journalist Paul Meyan from the Figaro. The idea of a private members’ club gradually began to take shape. The constitutive meeting of the Automobile Club de France, convened by the steering committee, was held on November 12th, 1895, at Count de Dion’s residence at Quai d’Orsay in Paris. The Count, however, did not wish to preside over the Club that he had helped inspire, leaving that honor to Baron de Zuylen, the first President of the ACF.

The club, initially located in Paris at 4, Place de l’Opéra, was inaugurated on April 15th, 1896. It then moved to the sumptuous setting of 6-8 Place de la Concorde.

EARLY MILESTONES OF THE A.C.F.

| 1895 | 1st Real motor race in the world: “Paris-Bordeaux-Paris”, the genesis of the A.C.F. |

| 1st Automobile Club in the world: creation of the A.C.F. | |

| 1897 | 1st Technical Commission:

|

| 1898 | 1st Motor Show. |

| 1st Automobile Manufacturers Trade Association. | |

| 1900 | 1st Commission for Tourism and its development. |

| 1st Technical Inspection Centre. | |

| The A.C.F. assigns colours to the racing cars according to their country of origin. Thus “France uses blue, Belgium yellow, America red and Germany white”. | |

| 1901 | 1st Automotive Laboratory: definition and control of standards. |

| 1904 | Creation of the “Association Internationale des Automobile Clubs Reconnus” (A.I.A.C.R.), today the “Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile” (F.I.A.). |

Paris-Marseille-Paris (September 24, 1896 – October 3, 1896)

Regulations for the Paris – Marseille – Paris race referred mainly to the repair of cars. Each car had to carry an observer chosen by the ACF. The competing vehicles were divided into three classes:

- Class A – Cars.

- Series 1 : Cars seating two, three, or four persons.

- Series 2 : Cars seating more than four.

- Class B – Motor Cycles weighing less than 150 kg – 330 lb (including tricycles).

- Series 1 : Motor Cycles without pedals.

- Series 2 : Motor Cycles with pedals.

- Class C – Any vehicle not entering into either of the above classes.

The Paris-Marseille-Paris race was the first competitive ‘city to city’ motor race, where the first car across the line was the winner, prior events having selected the winner by various forms of classification and judging.

The race would be run over ten stages with driving restricted to daylight. The start of the Paris-Marseilles-Paris took place near the Arc de Triomphe. From 52 entries thirty-one competitors actually started the race with twenty-three cars, three Leon Bollée voiturettes and five de Dion tricycles. After the first stage of 110.5 miles any thoughts of racing along a sun-drenched Riviera were dashed when the racers were hit by a torrential rain and near hurricane winds the next day. Trees and poles of all kinds were uprooted and then thrown onto the water drenched highways. The cars were hard put to stay on the road. Amedee Bollee crashed into a tree which was suddenly pitched into his vehicle’s path by the high winds. Others too found the roadways completely blocked. Still most of the competitors pressed on if they could, but by the start of the third stage, there were only sixteen water drenched survivors.

It was still raining hard during the third stage but the winds had now died down a bit. Emile Levassor the overall winner of the 1895 Paris-Bordeaux-Paris affair, led after the third section in the Panhard No. 5. On the fourth section Levassor hit a dog and the Panhard overturned. Emile was thrown out and was shaken up but appeared not seriously hurt. It seems however that he may have suffered some head trauma that would have tragic results the following years. His riding mechanic and co-driver, d’Hostingue, continued on in the race.

Fifty thousand Frenchman jammed the streets of Marseilles to watch the start of the return journey to Paris, under much better weather. At the finish their No. 5 entry had moved back up to fourth, while another Panhard No. 6 piloted by Emile Mayade (1853-1898), won by averaging 15.7 mph for the 1062.5 distance. There were fourteen finishers in all, the second day storm having understandably eliminated most of the field. The average speed was slightly higher than that of the 1895 Paris-Bordeaux-Paris race which was very impressive considering the horrid weather conditions which the racers endured on the 2nd and 3rd days of the race.

The gasoline/petrol internal combustion engined automobiles had shown their mettle under the worst possible and unforeseen circumstances and had passed with flying colours. Both the electric and steam carriages were now looking less and less viable compared to the gasoline powered vehicles though they would still leave their mark on the numerous speed trials that were being held. The winning No. 6 Panhard et Levassor, driven by Mayade, had a four cylinder, 8 horsepower motor. The Panhard cars placed 1st, 2nd (Merkel), and 4th (Emile Levassor-d’Hostingue) with their 2nd and 4th place vehicles were 6 horsepower models. De Dion tricycles place 3rd (Viet) and 5th (Collomb) overall. The highest placed Peugeot was 6th (Berlet).

Marseille – Nice – La Turbie (January 29-31, 1897)

Regulations for the race divided competitors into two classes.

- All four-wheeled vehicles.

- All three-wheeled type, tricycles or voiturettes.

The course for the race included a large portion of mountain roads and narrow switchbacks ending at the summit village of La Turbie, on the border with the principality of Monte Carlo. The race was won by Gaston de Chasseloup-Laubat driving a de Dion 18 hp steamer after a furious battle with Albert Lemaître driving a Peugeot. The winning time of 7 hrs 45 mins 9 secs over the 149 miles of the race gave an average speed of 19.2 mph. It was the last major win by a steam powered car over a road course. Georges Lemaître driving the Peugeot would finish 2nd followed by the Panhards of Charles Prévost Panhard and René De Knyff.

During the race Fernand Charron took a sharp corner downhill too fast and his car somehow turned a complete somersault, landing on all four wheels again with Charron still clinging to the tiller, although all the other things not tied down, including his mechanic were emptied out on to the road.

Paris-Dieppe (July 24, 1897)

The race was jointly sponsored by two French newspapers, Le Figaro and Les Sports and the A.C.F. The Panhards of De Knyff, Hourgieres and Prevost features extensive use of aluminum.

At a distance of 106 miles the race was won by the Panhard of Gilles Hourgières even though he trailed Paul Jamin’s Bollée (tricycle) and the Comte Albert De Dion 20 hp steamer at the finish. Coming in fourth overall wan another Panhard driven by Fernand Charron followed by another Panhard driven by Etienne Giraud who finished 7th overall.

After the start of the race a special train was on hand to take the VIPs to the finish line but broke down along the way causing the “very important” passengers to miss some of the leading finishers. The race also marked the introduction of the Grouvel & Arquembourg gilled-tube radiator on Girardot’s Panhard.

Paris-Trouville (August 14, 1897)

Regulations for the Paris – Trouville race split the event into two classes.

- Motor cycles weighing less than 200 kg – 441 lb.

- Cars seating at least two persons side by side.

Sixty-four starters left St. Germain at 10:00 on the 14th for the race of 173 kilometers to the French resort at Trouville was won by Gilles Hourgières driving a 6 hp Panhard et Levassor though he trailed Paul Jamin’s Bollée (tricycle) at the finish. He clocked an average speed of 25.2 mph for the 107.7 mile course. Following Hourgières was the Panhard of Albert Lemaître sporting a new grilled tube radiator and the 18 hp steamer of Comte de Dion.

Marseille-Nice (March 6-7, 1898)

Regulations for the Marseille – Nice race, for the first time, separated the little from the big cars.

- Class 1. Cars weighing more than 400 kg – 882 lb in running order (known as Heavy Cars).

- Class 2. Cars weighing 200 to 400 kg – 441 to 882 lb and two persons side by side (Voiturettes).

- Class 3. Motor cycles weighing between 100 kg and 200 kg – 220 to 441 lb; including tricycles.

- Class 4. Motor cycles weighing less than 100 kg – 220 lb; included 90 kg – 198 lb De Dion tricycles.

The the two-day race over a distance of 236 km was won by Fernand Charron driving a 8 hp Panhard et Levassor through a rain soaked, rut filled course. Gilles Hourgières, René De Knyff came in second and third, both also driving Panhards. Finishing 27th overall and 4th in her class was a driver of a De Dion motorized tricycle, who went by the name of Madame Laumaille – the earliest recorded woman racing driver.

Paris-Bordeaux (Critérium des Entraineurs) (May 11-12, 1898)

The race attracted only nine cars and thirteen cyclists started the race that stretched 357 1/2, miles and was marred by very bad weather on the second day. The race was won by René de Knyff driving the 6 hp Panhard at an average speed of 22.1 mph. This was the first victory for the Belgian de Knyff. He was followed by the Panhard of Fernand Charron two hours arrear with an average speed of 18.9 mph. with third being taken by another Panhard driven by Brueil. Jean-Marie Corre rode a De-Dion-Bouton tricycle to fourth place and was first in class.

Brussels-Spa (June 25-26, 1898)

The first town to town race in Belgium saw forty motor cars at the starting line. The race was won by Belgian born Baron Pierre de Crawhez driving a Panhard. Baron de Crawhez would later become the driving force behind the first closed circuit used for racing, the Circuit des Ardennes.

Paris-Amsterdam-Paris (July 7-13, 1898)

Regulations for the Paris – Amsterdam race divided cars, motor cycles and divers.

- Cars series 1. – seating 2 or 3 persons.

- Cars series 2. – seating 4 or 5 persons.

- Cars series 3. – seating 6 and more.

- Motorcycles 1. – weighing less than 100 kg – 220 lb, seating one person.

- Motorcycles 2. – weighing less than 100 kg – 220 lb, seating more than one person.

- Motorcycles 3. – weighing between 100 and 200 kg – 220 and 441 lb, seating one person.

- Motorcycles 4. – weighing between 100 and 200 kg – 220 and 441 lb, seating more than one person.

- “Divers” – all vehicles not entered into the above classes.

This event marked the first motor race to cross a national border reaching what was then the Dutch capital before retuning to Paris. The A.C.F. ran a special section for tourists, those who entered the event only for the pleasure mixed with thrill for the journey. The tourists section were allowed ten days to complete the course and were sent off two days before the regular racers.

Most of the Dutch spectators in the countryside had never seen an automobile in person and the crowds were thick along the route. The race almost did not get off the ground when the Monsieur le Préfet (Police) took the opportunity to demand a certificate of road fitness for each newly constructed vehicle and a man named Bochet, the engineer in charge, duly deemed one car after another unfit! It should be noted that the regulations used to determine fitness were based on previous motor cars and due the progress taking place in their design many of the regulations were now obsolete. The cars that were deemed unfit had to be drawn by horses to a starting point outside the Préfet’s jurisdiction, in the town of Villiers. Forty-eight starters finally got away at thirty-second intervals but only fifteen worn-out returned to the improvised finish line at Montgeron, Of those seven were Panhards led by Fernand Charron driving a 8 hp Panhard. He was followed by Léonce Girardot also in a Panhard. They were hounded by the Bollée of Etienne Giraud. George Heath became the first American to race abroad and finished 13th.

Paris-Bordeaux (May 24, 1899)

This year’s event, reflecting the increased speeds of the cars would be run in a single stage of 351 miles and was sponsored by the French newspaper La Vélo. The race was won by Fernand Charron driving a 12hp Panhard at an average speed of 29.9 mph. He was followed by the Panhards of René de Knyff and Léonce Girardot. A Mors driven by a driver racing under the name of Antony came in 6th. Two Decauville voiturelles driven by Leon Théry, Fernand Gabriel, names that would soon become famous, failed to finish.

Tour de France (July 16-24, 1899)

Regulations for race the divided contestants into three classes.

- Cars with at least two places side by side and two passengers of 70 kg – 154 lb weight.

- Motor cycles weighing less than 150 kg – 330 lb.

- Any vehicle not entering in the above categories.

Organized by the French newspaper Le Matin the race covered 1,378 miles, of which 1,350 miles were competitive and consisted of seven stages: Paris-Nancy; Nancy-Aix-les-Bains; Aix-les-Bains-Vichy; Vichy-Périgueux; Périgueux-Nantes; Nantes-Cabourg; Cabourg-Paris. Out of forty-nine starters, twenty-one vehicles finished.

The cars taking part were mainly Panhards, Bollées and Mors with single entries from Georges Richard on a car of his own make and Dr Lehwess with a Vallee. Lehwess did not reach Nancy. The Panhards, of which there were eight, looked the most conventional and workmanlike but the most attractive were the Bollées with their long wheelbase, low slung suspension and streamlined torpedo bodies.

From the start, however, it was a Panhard driven by the Chevalier Rene de Knyff who dominated the event. He was fastest on every stage and came back to Paris having averaged 30.2mp. On the sixth day of the Tour de France Fernand Charron found himself near Le Mans with a car which would only travel in reverse; but as at that time he was third in the race he refused to be daunted and drove 25 miles into Alencon backwards, sitting on the bonnet of his car. Unfortunately he would not finish the race.

Paris – Toulouse – Paris (July 25, 27-28, 1900)

Regulations for the race divided competitors into three categories.

- Cycles weighing less than 250 kg – 551 lb.

- Voiturettes weighing less than 400 kg – 882 lb.

- Cars weighing more than 400 kg – 882 lb.

Public interest in this race was at a fever pitch due to the rise of Mors as a legitimate challenger to Panhard et Levassor. The distance for the race was a daunting 837. 1 miles that would be run in three stages, one outbound and two inbound with a day of rest in between. There were nineteen starters in the heavy car class and of those eight would finish the race. The race was won by Levegh driving 24 hp Mors a who took a commanding lead from the start and was never seriously challenged. His winning time was 40.2 mph.

Paris-Bordeaux (May 29, 1901)

Race regulations introduced one new racing category. The four classes based on weight were used for the first time in this race and remained almost unchanged over the next six years.

- Over 650 kg “two-seated cars” or heavy cars, the ultimate racing machine of the time.

- 400 to 650 kg “light cars”

- 250 to 400 kg “voiturettes”

- Under 250 kg Motor cycles (including tricycles)

The 1901 edition of this event saw sixty entrants and included the Gordon Bennett Cup. At 4:00 am the sleep deprived races were sent of with the Cup entrants leading the way. The Cup entrants were limited to those from France when Napier’s car was ruled ineligible due to it’s use of French tires. Léonce Girardot would take the Cup while in the overall race it was Mors’ new star, Henri Fournier, Charron’s former riding mechanic, driving a 60 hp Mors who would come in first at an average speed of 53 mph.

Paris-Berlin (June 27-29, 1901)

Race regulations included a rule requiring all cars to have the exhaust arranged in such a way as not to impinge upon the ground or disturb the dust on the road. The race run over three days:

- June 27th Paris-Aachen, 285 miles

- June 28th Aachen-Hanover, 278 miles

- June 29th Hanover-Berlin 186 mile

Henri Fournier driving a 60 hp Mors won the event.

See race report: Faster than the Express Train

Paris-Vienna (June 26-29, 1902)

The ACF set a maximum weight regulation of 1000 kg – 2204 lb for Heavy Cars, the premier class. This rule was first applied at the Circuit du Nord. The Paris – Vienna race was run also to this rule with the addition of allowing 7 kg – 15.4 lb extra if a magneto was fitted.

The Paris-Vienna race was run concurrently with the Gordon Bennett Cup race that ran from Paris to Innsbruck, Austria where the rest of the field would continue to Vienna. This comprised 565 of the entire 990 km race. The Gordon Bennett entrants were scheduled to start ahead of the other Paris-Vienna entries. In the early stages of the race Chevalier René de Knyff driving a Panhard led both the overall race as well as the Cup entries.

The second day took the competitors through Switzerland, where motor racing was banned, and so this was deemed a neutralized section with cars required to adhere to a speed limit of 15 mph. The poorer road surfaces in Switzerland contributed towards a crack beginning to develop on the casing of the differential on de Knyff’s Panhard. By the third day de Knyff continued to lead until 40 km before Innsbruck, when his damaged differential finally failed forcing him to retire whilst traveling over the Arlberg pass which proved a strong test of both man and machine. It started with a tough 6000-foot climb up a wagon road crossed by car-killing drainage ditches. On the trip up and down the other side, racers had to avoid the vertical rock slabs which were used to keep out of control wagons from plunging over the steep sides. There were more than a dozen accidents on the decent caused by burned out brakes, leaving the racers no other means of slowing down other that crashing into the inner wall of the pass.

The Cup was won by Britain Selwyn Edge driving a Napier. Nobody had given the Renault 28 hp Type K (Light Car) much of a chance alongside large and powerful vehicles like Count Zborowksi’s Mercedes and Henry Farman’s Panhard. But the Type K’s light weight worked wonders on the steep roads and Marcel Renault crossed the finish line 1st, having covered 1,300 km at an incredible average speed of 62.5 kph!

See race report: 1902 Paris – Vienna Motor Race

Paris-Madrid (May 24, 1903)

The French Parliament reacted strongly to the news of the numerous accidents. An emergency Council of Ministers was called and the officers were forced to shut down the race in Bordeaux, transfer the cars to Spanish territory and restart from the border to Madrid. The Spanish government denied permission for this, and the race was declared officially over in Bordeaux. The cars were impounded and towed to the rail station by horses and transported to Paris by train. Newspapers and experts declared the “death of sport racing”. It was a common thought that no other races would be allowed, and for many years it was true. There would not be a major race on public roads until the 1927 Mille Miglia.

See race report: The Race to Death