Cooper Cars

Charles Newton “Charlie” Cooper, the son of an actor also named Charles was born in Paris, France, on the 14th of October 1893 and spent his early years in France and Spain. After the death of his wife his father moved the family, consisting of Charles and his two sisters back to England, just south of London. On leaving school, Cooper was taken on as an apprentice at Napier & Son’s engineering works in Acton.

It was while working at the Napier plant that Cooper got his first taste of motor sport, working on the racing and record-breaking cars of company director and winner of the 1902 Gordon Bennett Cup, Selwyn Edge. When World War I broke out Cooper wasted no time in enlisting in the Royal Army Service Corps. He saw saw action on the Western Front and was invalided home after being gassed during the capture of Valenciennes. in 1919 Cooper decided to set up his own garage on Ewell Road in Surbiton where he refurbished war surplus motorcycles and would compete in local trials. It was during the trials that he met Irish born motorcycle, automobile and speedboat racer, Kaye Don. In 1921 Don began racing at Brooklands and would later ask Charles to help maintain his racing cars.

During World War II, the company stayed afloat maintaining fire service vehicles which due to the bombing were in heavy use. After the war England’s economy was shattered, the effects lasting more than a decade. In 1948 life in post-war Britain was desperately gray and dull, even the London Olympics, called the Austerity Games, offered only a temporary respite. Everything worthwhile still seemed to be rationed, including petrol. Then when the Government cancelled the ‘Basic’ petrol ration private motoring was effectively banned. Unless you had a business allowance you had to use public transport, or somehow fiddle the fuel for your private car. In fact, the motoring public seemed more determined than ever to travel and find some fun, despite the gloom. Fuel rationing would finally be lifted in 1950. Luckily race cars ran on methanol which was available but expensive, though hauling the car to and from races was still a major problem.

To compound things there were also no functioning racing circuits in Britain. Brooklands was derelict and partly demolished. Donington Park, near Derby, was an enormous military transport depot, and London’s Crystal Palace was abandoned and overgrown. Any racing was confined to sprints and hill-climbs. Suggestions were made to use the abandon aerodromes dotted all over Britain and this at least would provide a proper tarmac to race on.

500cc Cooper

The Charles Cooper built his first racing car in 1936. This was a special based on an Austin Seven. After serving with the Royal Air Force during the war, Cooper and his son John decided, in 1946, to build a car for the new 500cc racing series. They used a JA Prestwich Industries (JAP) Speedway motorcycle engine. JAP built their first motorcycle engine in 1902. Their engines proved very popular and could also be found in aircraft as well as some of Britain’s lightweight cars such as the three-wheeled Morgans. British 500 cc ‘poor man’s motor racing’ movement had been founded by some Bristol enthusiasts. John and Eric wanted all independent suspension on their car, so they took two Fiat Topolino front ends — which had simple wishbone-and-transverse-leaf-spring independent suspension — and welded them together back-to-back.

The engines came from motorcycles, where chain-drive was de rigeur. ‘So when we came to make our first 500cc racer, it was just a hell of a lot more convenient to have the engine at the back, driving a chain. We certainly had no feeling that we were creating some scientific breakthrough! Don’t forget, our Cooper-Bristol F2 car was front-engined. But we put the engine at the rear in the 500s because it was the practical thing to do.’ – John Cooper

They installed an air-cooled single-cylinder JAP speedway engine in the rear, chain-driving to a solid rear axle, and then encased it with an aluminum single-seat body. These two Cooper-JAPs were so successful that other enthusiasts soon requested their own cars. One of these enthusiasts was Stirling Moss who up to that time raced his 2-itre BMW Typ 328 sports cars mostly in trials, who recalled: During 1947 we had seen and read about the new Cooper-JAPs. They fascinated me — real racing cars with single-seater bodies and open wheels, and affordable! “I discovered Cooper’s Garage in Surbiton, and one day that autumn contrived to drive past with my father in the car. One of the prototype 500s was in their little showroom. We stopped. ‘Gosh Dad look at that, wouldn’t it be terrific to have one of them for next season?'” It would be the first “real” race car Moss ever drove. The 500cc formula became known as Formula 3 in 1951 and Cooper chassis proved to be a roaring success and were raced all over Europe.

As the cars progressed drivers were looking for more power which was supplied by Norton. The Norton Manx was originally designed in 1927 by Norton’s Chief Designer, Walter Moore. A long stroke (79 X 100mm) overhead cam single, it was reliable and powerful enough to bring Norton success at the Isle of Man in that year. Joe Craig took over responsibility for the racing department and, in 1938, modified the valve gear operation to “double knocker” form. The engine provided around 10% more horsepower, but at first, Norton refused to sell engines alone so wealthier competitors purchased complete bikes and sold the leftover spares, inadvertently this helped create a complete new motorcycle, the Triton, when riders began mating the stripped Norton Featherbed frame with an easily available Triumph engine. Through the years, a number of developments were introduced including a combined, forged, main shaft and flywheel, additional piston rings, and the introduction of an all aluminum head. The stroke was reduced several times during the fifties until Norton officially withdrew from racing in 1956. Other notable marques included Kieft, JBS and Emeryson in England and Effyh, Monopoletta and Scampolo in Europe.

By 1949 Cooper’s basic 500 had evolved into their Mark III design which had cast magnesium wheels which were lighter than the cast aluminum originals, and a new combination fuel and oil tank above the engine. An extra 8.5 – 9 gallons could be carried in a scuttle tank above the driver’s legs and if necessary others could be inserted beneath the seat or slung alongside in a pannier. The seat back was raked to give more cockpit space and for those who wanted to fit a 1,000 cc twin-cylinder engine for Formula B there was a stretched- wheelbase chassis option.

The historian, Doug Nye estimated that before World War II there were probably less than three-dozen worthwhile pure-bred racing cars in the whole of Britain. Racing was chiefly under the purview of the moneyed class. Brooklands’ motto was The Right Crowd and No Crowding. No average bloke could ever hope to become a racing car driver, there was no money in it except that which would be paid out for cars and equipment. After the war however thousands of returning soldiers had gained experience maintaining and driving all manner of military vehicles.

The Minister of Fuel and Power, Philip Noel-Baker, told the House of Commons rationing would be abolished because two American companies had agreed a deal to supply oil in return for buying British goods. The BBC reported that on the 26th of May, long queues have appeared at garages this evening and motorists have torn their ration books into confetti after the government announced an end to petrol rationing. “This is indeed VP [Victory for Petrol] day for the motor users’ campaign,” said a spokesman for three motoring organizations – the RAC, AA and Royal Scottish Automobile Club.

Cooper – Bristol

Many of Coopers customers were eager to move up the racing ladder and that meant Formula 2. For this Cooper needed an engine of sufficient power and the company turned to an engine made by the Bristol Aeroplane Company based the six-cylinder engine’s design of the pre-war BMW 328. The engine displaced 1971cc produced nearly 130 horsepower though about 40 horsepower less than the competition. To compensate for its lack of power, Cooper devised an uncomplicated and lightweight front-engined chassis. The resulting car was the Cooper T20, also known as the Cooper-Bristol Mark I (MKI). The car was given a four-speed manual gearbox and a traditional Cooper suspension that included transverse leaves and tubular wishbones.

Family friend Bob Chase acquired a Formula 2 Cooper-Bristol T20a for Mike Hawthorn to race during the 1952 Grand Prix season. At Goodwood’s Easter Monday meeting Hawthorn won the F2 Lavant Cup and Formula Libre Chichester Cup before finishing second in the Non-Championship F1 Richmond Trophy, only beaten by Jose Froilan Gonzalez’s 4.5-litreFerrari 375. At the Belgian GP, it was driven to a spectacular fourth place finish, a third place finish in the British GP was achieved, another fourth at the Dutch GP, which combined earned Hawthorne a fourth place finish in the World Championship and would launch his Formula 1 career. The Cooper-Bristol T20 often outclassed the more powerful cars, though they were still no match for the Ferrari’s of Ascari, Farina and Taruffi. It was Cooper’s first Formula 2 car and was replaced in 1953 by the T23, also known as the Cooper Bristol MKII.

1.5-Litre Formula 2

Established in 1903 by former Daimler engineer Pulham Lee to design engines for small car companies and for specialist applications, Coventry Climax first became well known for supplying motors for the tractor used by Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Antarctic Expedition in 1914. After World War I the company began supplying engines for small car companies such as Clyno and in the 1930s expanded to include Triumph, Morgan and Standard. After World War II the Ministry of Defense changed its requirements for fire-pumps, demanding a faster flow and lighter weight. In 1950 Leonard Lee hired Jaguar engine designer Walter Hassan to design a new pump and he produced the 1020cc Feather Weight engine, known as the FW. The engine was displayed at the Motor Show in London and attracted attention from the motor racing fraternity. Leonard Lee, Pulham’s son concluded that success in competition would lead to more customers for the company and so he had Hassan design the FWA, a feather weight engine for automobiles.

Starting in 1956 the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI) announced a new 1500cc engine rule for the following F2 season. Charles and John Copper were quick to see the economic opportunity that this new series could offer. John Cooper visited Coventry Climax and remarked to Leonard Lee that their FWA would be ‘a lovely’ engine to put to put in the back of one of their Copper racing car to which Lee responded with a pair of engines for Cooper to ‘try out’.

To go racing they needed a suitable gearbox to apply what at that time was only 84 hp, to the rear wheels. Using a Citroën gearbox that they grafted on to their motor made it apparent that they needed one more speed added to the 3-speed unit. A 4-speed conversion designed in house but built by ERSA of Paris solved the problem, at least initially. The first application for this new power unit was actually in a sports car. Maddock had read about a German aerodynamicist named Professor Wunibald Kamm who suggested that reducing car turbulence at high speeds by truncating the rear bodywork; the style of car bodywork based on his research has come to be known as a Kammback or a Kamm-tail. John Cooper and the rest were not keen on the looks of the car but Cooper convinced everyone that the car wouldn’t fit in the transporter otherwise! Known as the ‘Bobtail” Cooper-Climax T39, the sports car, with the driver sitting along the centerline proved very popular.

Owen Maddock removed the panniers and formed a body around their new single-seater chassis and in 1959 John Cooper convinced Coventry Climax into building full-sized 2 ½-litre engines for his works drivers – Jack Brabham and Bruce McLaren. It was Moss, who scored the new Cooper’s first major victory during the non-championship Glover Trophy at Goodwood. Little over a month later Brabham scored his first win with the Cooper T51 during the International Trophy at Silverstone. The season turned out to be a three-way battle between the factory Cooper of Jack Brabham, the Rob Walker entry driven by Stirling Moss and the Ferrari of Tony Brooks. Into the last race at Sebring, Brabham was leading the championship from Moss and Brooks. Bruce McLaren won the race, Moss retired, again with transmission problems and Brooks finished third. Brabham’s car ran out of fuel (not for the first time) on the final lap. A momentous effort saw Brabham push his stricken T51 over 400 metres, up the hill across the finish where he collapsed. He was placed fourth in the race and scored enough points to claim the Championship. In 1960 Brabham had a much easier time of it and again won the World Championship, this time ahead of his teammate, Bruce McLaren.

Cooper Comes to Indianapolis

“Why the hell don’t you try?” he insisted. “Why don’t you come to Indy as soon as you can? I’ll get things organized so that you can use the track for a time. That’s all you need. My pleasure’s going to be the looks on a lot of those guys’ faces at the track. Boy, are they ever in for a surprise!”

Roger Ward – The American Indianapolis 500 Champion had met John Cooper previously and suggested that he take one of his cars to Indianapolis for the 500.

Cooper took one of the championship-winning Cooper T53 ‘Lowlines’ to Indianapolis Motor Speedway for a test in 1960, then entered the famous 500-mile race in a larger, longer, and offset car based on the 1960 F1 design, the unique Cooper T54. Arriving at the Speedway 5 May 1961, the “funny” little car from Europe was mocked by the other teams. The fact that it was painted green, considered unlucky only compounded the problem. Two drivers stood out to Brabham as especially helpful, Eddie Sachs and Roger Ward who actually went out for a spin in the car. In the race Brabham ran as high as third but a late, balky pitstop pushed him back to ninth. It took a few years, but the Indianapolis establishment gradually realized the writing was on the wall and the days of their front-engined roadsters were numbered.

1961 was the first year of the 1.5-litre formula and was dominated by a well-prepared Ferrari team. Only Stirling Moss, in an outdated Lotus, was able to beat the Ferraris on two tracks where his skills offset the Ferrari power advantage. Cooper’s drivers Brabham and Mclaren could only manage an 11th and 8th respectivly. By 1962 Brabham had left to form his own team and the other British teams, Lotus and BRM had now caught the team from Surbiton, with BRM’s Graham Hill claiming the World Driver’s Championship, Jim Clark’s Lotus finishing 2nd. Cooper’s Formula 1 glory was now firmly in the past. Two years later Charles Cooper was dead and a year later the Formula 1 team sold.

Mini-Cooper

When John Cooper first saw the Mini it reminded him of a shoe box on wheels but after driving it he immediately recognized that the same features that made the original Mini such an innovative people mover – a transverse engine, four wheels pushed out to the corners and minimal size – also gave the car incredible balance, an extremely wide stance and amazing agility. Just the attributes needed to turn it into a small, but ferocious racer. Cooper suggested to George Harriman, head of the British Motor Corporation (the Mini’s manufacturer), that he should market a tuned-up version. Harriman doubted that he could sell more than 1,000; the final total of owners attracted by Cooper’s modifications exceeded 125,000. Named the Mini Cooper, the car dominated saloon car and rally races throughout the 1960s, winning many championships and the 1964, 1965, and 1967 Monte Carlo rallies. The Cooper name was later licensed to BMW who had purchased the Rover Group, current owners of the Mini line for the higher-performance versions of the cars, inspired by the original Mini, now sold as the MINI. John, along with his son Mike Cooper, served in an advisory role to BMW and Rover’s New MINI design team.

John Cooper

After the death of his father, John Cooper sold the Cooper Formula One team to the Chipstead Motor Group in April 1965 but continued to co-direct the F1 team (with Roy Salvadori) into 1968, before it closed in May 1969. The last surviving Formula One team principal from the formative years of the sport, and he often lamented later in life that the fun had long since gone out of racing. He helped establish Britain’s domination of motorsport technology, which continues to this day, and he received the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for his services to British motorsport. John Cooper remained head of the West Sussex family garage business and died on the 24th of December 2000.

Cooper were considered pragmatists with a mechanical rather than purists approach to race car building as opposed to the design-led Lotus, or the intensive engineering of BRM. In a sense they never really left the garage and for the period that covered their glory years, that was enough. Sir Jack Brabham:

“Without John, Cooper’s would have petered out very early on, because his father, Charles, simply would never spend the money once they’d first made their mark. Once a Cooper was winning his attitude was, ‘Why change it?’, while we knew we had to change to catch up or to keep ahead. It was John who covered for us so Charlie wouldn’t know we were getting the ZF limited-slip diffs and the strengthened ERSA gearboxes, and then our own gearbox for the 1960 Lowline car. Without them we wouldn’t have won a thing. John just kept saying, ‘Don’t tell The Old Man’. Yet when we won, Charles Cooper absolutely loved it. John really was a great bloke. A great friend.”

Owen Maddock

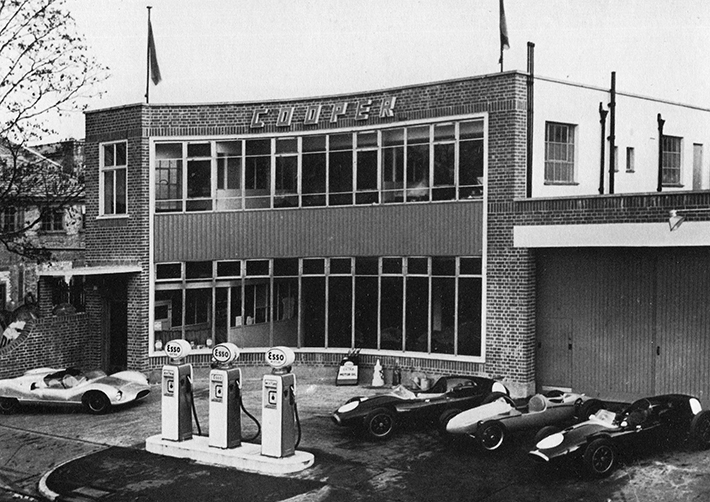

Owen Richard Maddock was the chief designer of the Cooper Car Company during the 1950s and early ’60s. The son of architect Richard Maddock, who designed the Cooper factory in Surbiton, Owen studied engineering at Kingston Technical College while with the Home Guard in the last years of World War II, and then spent two years doing National Service in Germany.

Upon his return to England, he joined the fledgling Cooper Car Company. Not able to afford taking on a full-time engineer. Maddock in addition to his drafting duties Maddock also served as a fitter, storekeeper and van driver. ‘The Beard’, as he became known by his colleagues, was an outstanding lateral thinker and was soon designing cars radical for their time. His ‘bent tube’ chassis which broke standard engineering practice and became a standing joke, until 1958 when Stirling Moss raced to victory in Argentina — the first championship grand prix win for a mid-engined car.

During Cooper’s championship years the design process involved Maddock, John Cooper and star driver Jack Brabham barnstorming ideas while Maddock would later draw up the plans. Maddock’s protégé and eventual successor, Eddie Stait, later recalled to historian Doug Nye that “John had a lot of the original ideas and then Owen would add some very original thinking in developing those ideas; they were a team … and Jack of course contributed a lot.”

Maddock was also a sousaphonist (tuba), performing with Mick Mulligan’s Magnolia Jazz Band. Maddock left Cooper in 1963, drawn by the desire to build a racing hovercraft, and formed the Hover Club of Great Britain. He freelanced for McLaren and March, but turned down permanent positions and spent the last 20 years living on the Isle of Wight, continuing to enjoy his music. Owen Maddock died on July 19, 2000.