1930 Bentley Speed Six

A bloke couldn’t think of anything more dissimilar if he tried. From a Boeing 737, to a modern Korean buzzbox, to a 1930 Bentley Speed Six. While both the jet and the Hyundai with its automatic transmission and power this-and-that were purely means of transport, the Bentley was so completely different. Would it be trite to say that it was the epitome of Le Mans during a time when automotively inclined Brits wanted to hop across the Channel to show the Frogs how to win a motor race?

That certainly crossed my mind, but while the Bentley Speed Six of Barry Batagol looked the part, with its open touring style bodywork, it’s interesting to realize that most Bentleys of the period were originally fitted with closed saloon bodywork.

While that was true, it was more than that. Sure, the knowledge of a Speed Six winning at Le Mans in 1929 and ’30 was there, but it came home to me when we were about to drive through roadworks where the road surface was a mix of water, mud and soft tar. I suggested that we should try and avoid it and Barry said that I shouldn’t be too concerned. I said that I was concerned that much would end up on his car. “Then I’ll clean it!” came the answer.

It instantly became clear, as owning and driving a W.O. Bentley was not all about driving a great looking motor car, but more of a frame of mind. Bentleys, especially those made at Cricklewood, were meant to be driven and enjoyed. So what if they get a bit dirty?

Shining

It was destined to be a shining light in the British automotive industry for a few short years, from 1919 to 1931, but the impact of the cars built at the original Cricklewood works is still being felt today. Of course, the name of Bentley still exists, under the ownership of Volkswagen, and while the modern version remains a cut above most other marques, there is really no comparison between what we now call W.O. Bentleys and those of today. That doesn’t stop, however, the modern organization from capitalizing on the deeds of the past.

Walter Owen (W.O.) Bentley was born in London, in 1888, and at 16 started a five-year apprenticeship with the Great Northern Railway. After his apprenticeship, W.O. teamed with his brother Horace Millner (H.M.) Bentley to form “Bentley and Bentley” to sell French DFP cars. Toward the end of his time with Great Northern Railway, W.O. tried his hand at some early motorcycle racing. It was an interest that would later greatly influence the promotion of the Bentley car.

During this time, W.O. became profoundly interested in the fitting of aluminum pistons to engines, while cast iron was the norm. A DFP fitted with aluminum pistons was driven by W.O. at Brooklands, in 1912, where it set a number of records. W.O. was an exponent of aluminum pistons, especially in rotary aero engines, and the commencement of World War I found him convincing manufactuers Rolls-Royce and Sunbeam to use them. W.O. soon found himself commissioned in the Royal Naval Air Service working on the design of aero engines. Bentley did not meet with success with Gwynnes Limited, the manufacturer of Clerget engines, so the British Navy provided him with a team to design his own aero engine at the Humber factory.

Over time W.O. would design two aero engines, both of which were to prove popular with aircraft manufacturers during the war.

Following hostilities, W.O. was awarded £8,000 for his design and with his brother H.M. used this sum to establish Bentley Motors Limited at Cricklewood, just six miles from the center of London. Understandably, the Bentley brothers gathered together a team they had previously worked with, including Clive Gallop who would go on to design a very advanced three-liter, four-cylinder engine. So advanced that it included an overhead camshaft, four valves per cylinder and was of Monobloc construction (cylinder head and block cast as one). The camshaft was driven by a geared vertical shaft from the crankshaft at the front of the engine.

The first three-liter Bentley was on the road in 1919, but not released for sale until 1921. The model set the tone for all future vehicles that came from Cricklewood with its separate four-speed gearbox, right-hand gear change and sold as a rolling chassis, meaning that purchasers were to decide on the coachbuilder. In the main, this was an advantage to W.O. as it saved him the concern of coachbuilding, but right from the beginning Bentley thought his cars were of a sporting type and therefore should be fitted with lightweight four-seater bodywork. That wasn’t to be the case, though, as most were fitted with heavy, all-weather four-door saloon bodywork.

Sporting

While owners were having saloon bodies fitted to their new Bentley chassis, W.O. himself remained convinced that competition was the best way to market his cars. In 1922, a three-liter was sent to the Indianapolis 500 race and while outclassed, it did achieve a credible 81mph. Later cars were prepared for the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy and a lone 3-liter was run in the very first Le Mans of 1923, where it finished 4th overall. The following year a 3-liter won the 24-hour race.

The 3-liter Bentley was a sporting car, but with heavier and heavier bodywork being fitted, more power was needed. Design work started in 1924 on a larger six-cylinder-powered car, which was announced to the public in October 1926. It was a bigger car, but then again the engine had grown to 6 ½ liters, while the SOHC remained as well as the four-valves per cylinder and Monobloc construction. Available as the Bentley 6 ½ liter, until in late 1928 a more powerful version was released with the name of Speed Six, however the earlier car stayed in production as the Standard Six. Understandably, over time the Speed Six would eventually become more popular than its predecessor. The 3-liter Bentley also stayed in production until mid-1929.

In among the four- and six-cylinder cars, in 1927 Bentley introduced the 4 ½ liter, which many saw as the replacement for the three-liter. However, this was not the case as while the engine’s camshaft drive was a front-mounted vertical shaft, its bore and stroke were the same as the six-cylinder.

Competition for Bentley went from success to success with wins at Le Mans four years in a row. A 3-liter in 1927, a 4 ½ liter in 1928 and then back to back in 1929 and 1930 with a Speed Six.

What wasn’t a success were the Bentley account books, as while W.O. was a brilliant engineer, his expertise didn’t extend to the ledgers. In fact, on reflection it’s hard to understand how the company stayed afloat as it was practically a financial roller-coaster ride virtually from the day it was formed. Eventually, in 1926, much needed funds were injected into the company by Joel Woolf Barnato, who had bought his first Bentley in 1925 and became inspired by the marque’s success at Le Mans so much so that he bought the company. Barnato would eventually go on to win at Le Mans driving Bentleys in 1927, ’29 and ’30. If it wasn’t for the injection of funds from Barnato it is doubtful that there would have been a 6 ½ liter or a 4 ½.

Losing Control

With the funds from Barnato, W.O. was losing control of his company. This came to the fore when Barnato gave approval to the construction of what we now know as the Blower Bentley. W.O. was strongly against its construction, but it went ahead as Bentley Motors was no longer his.

Then Wall Street collapsed, in October 1929, and it wasn’t long before those who previously bought Bentleys were no longer spending their money on luxury items.

Despite the financial difficulties, Bentley had another card up its sleeve in the form of the 8 Liter. A massive car with abundant performance that was probably buil, because it could be, and not because it was sanctioned by the accountant. The Bentley 8-Liter was one of the great cars of the period, but it probably sounded the death knell for the financially strapped company. Financially, it was the wrong car for the wrong time.

History and many W.O. Bentley owners also say that another model, the 4-liter Bentley, was also the wrong car. As perhaps another showing of how W.O. had lost control, the Bentley Board authorized the production of a new model powered by a 4-liter engine designed by Harry Ricardo, featuring a cast iron block and detachable cylinder head also in iron. The Board was concerned about the lack of sales of the aging 4 ½ and 6 ½ liter models and sought to modernize through a new model. It was not a success and is not looked on fondly by W.O. Bentley owners today.

By the end of 1930, W.O. had been removed as head of Bentley Motors with new directors appointed. Despite efforts to keep the company afloat, receivers were appointed on July 10, 1931. It soon became apparent that the Napier car company was a prospective buyer of Bentley. It seemed to be a perfect end to a bad situation, however when news of this reached Rolls-Royce, that company’s directors were concerned that Napier was on its way back to quality automobile production using Bentley and W.O.’s expertise.

When the matter went before the courts there were two prospective buyers—Napier and a company that no one had heard of— British Central Equitable Trust Ltd. The latter, of course, was a front for Rolls-Royce and when the bids for Bentley Motors were announced they were the winners.

With Bentley Motors taken over by Rolls-Royce, W.O. found himself in the situation that he was legally forced to go with what was previously his company. He stayed with Rolls-Royce until 1935 as a test and development advisor.

It can’t be said that Bentley Motors, under Rolls-Royce control, flourished in its previous guise. While the Bentley name continued, production was moved to Crewe and over time the cars shared more and more components with Rolls-Royce vehicles.

Later W.O. joined Lagonda and designed a V12 engine for a car that would go on to achieve 3rd and 4th at Le Mans in 1939. After WWII, of course, W.O. designed the Lagonda DOHC 3-liter engine that would eventually find its way into the David Brown Aston Martins. W.O. would then set up his own consultancy business and did work for the likes of Armstrong-Siddeley before retiring in 1950. He died on August 13, 1971.

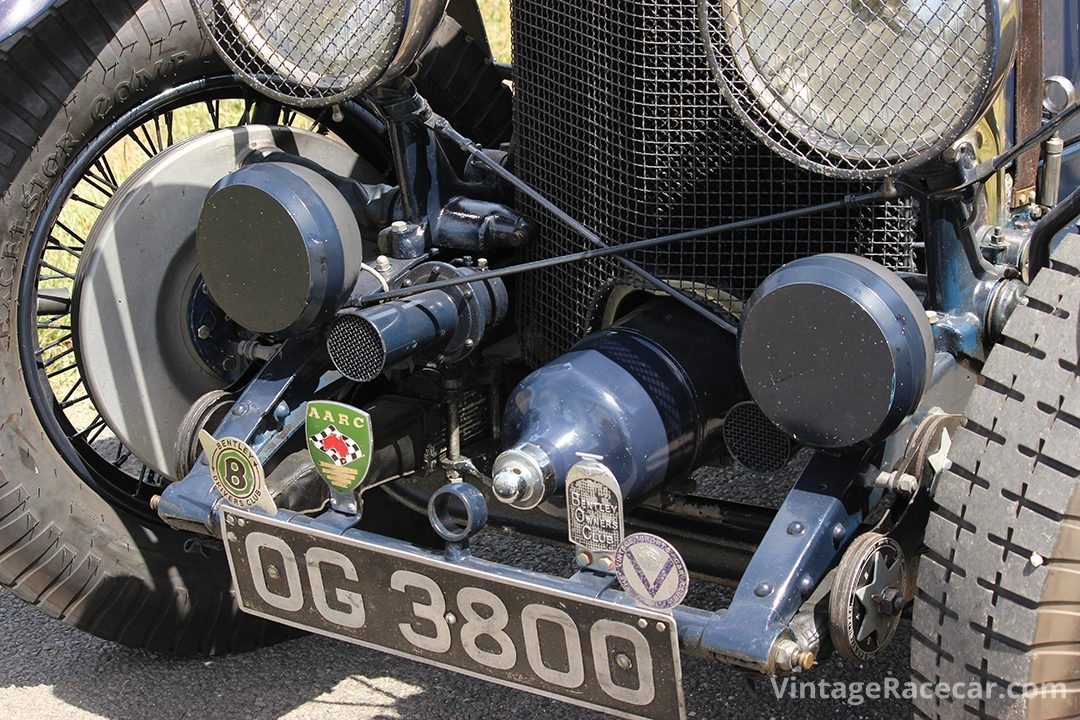

Barry’s Speed Six

“It’s amazing how things turn up,” Barry said. “Clare Hay is the recognized world expert of W.O. Bentleys and was recently in Australia assisting The Bentley Drivers Club of Australia in the preparation of a book on the history of W.O. Bentleys in this country. She presented me with photos of my car taken back in 1948, which amazingly she found on eBay for ten Quid or something. She managed to identify the car by looking closely at the firewall because there is a missing switchbox that’s been missing since the car was new.”

Clare had a very close look at the car when she was in Australia and prepared a lengthy report on her findings. She described it as, “In general, LR2786 is a very correct, original chassis with all its original matching numbers with some concessions to long-distance touring, fitted with a good quality VdP style four-seater body.”

Barry’s Bentley (chassis LR2786) is a late Speed Six, built in 1930, on the 11-foot, 8-1/2-inch wheelbase chassis. Like all W.O. Bentleys, it was sent without body to a coachbuilder—in this case Salmons & Sons—for the fitting of a saloon body. While formed in 1830, Salmons & Sons initially built horse-drawn coaches, but found success with the advent of the automobile. The company would stay in business until the retirement of the last of the Salmons family, and then was renamed as Tickford Ltd. in 1943.

The car was returned to Bentley for final checking before it was released to a dealer in Birmingham and delivered to its first owner. It stayed in the UK through to the mid-1950s, after which it was bought by William Klein in the U.S. William and Ann Klein were enthusiastic collectors of vintage Bentleys and gathered together quite a number in the days when they were not bringing very much money. It was then sold back to the UK where it was fitted with a Vanden Plas four-seater touring body in preparation for long distance rallying. In that guise, it was purchased and shipped to a collector in Melbourne, Australia. After which it passed into Barry’s hands in 1993.

“Yes there have been a few older cars,” Barry said in answer to my question. “I see myself as just the custodian of them all, including the Bentley. I have been interested in cars since I was a kid and used to buy all the magazines available so I could read about them. I remember reading about W.O. Bentleys winning at Le Mans, and lots of others marques until you get to a stage in your life when you have a list of cars in your mind that would be nice to own one day. While I am certainly not the same vintage as the Bentley, it doesn’t stop me from appreciating the older cars. As you know, the older cars in many ways are more fun to drive, while modern cars are less fun—or less ‘grin factor’ as I like to put it.

“There have been a number of cars that have provided plenty of grins including an Austin-Healey 100, a Sprite, Lotus Elan and some early Ferraris including a 750 Monza and a SuperAmerica. I’m interested in all sorts of cars, not any particular marque as I think all cars are wonderful and all have good and bad points. They are all different, such as the Lotus, which is a precise little car and such a contrast to the Bentley. They all have their own place, but I suppose the advantage of this car is that it’s something I can enjoy with my wife. We do long rallies together as it isn’t so selfish as a sports car that you end up driving by yourself.

“I used to have a 289 AC Cobra and then the owner of the Bentley wanted it, so we worked out an arrangement resulting in the Speed Six coming my way. Looking at the Bentley’s history, I have now owned the car for longer than anyone else in its life.

“I actually saw the Bentley some 15 years before I bought it and was just gobsmacked by it. The sheer presence of the car really impressed me, and then there was the performance of a Speed Six and the history of the model at Le Mans.

“When I got the car its condition was very much like it is now. Since then I have fixed things when they needed fixing and maintained the rest. It hasn’t been painted during my ownership, and it’s still the same trim. Mechanically, things like brake linings that wear out have been replaced, as have the tires. I did pull the engine down, as a sort of pre-emptive test, just to make sure everything was okay. Turned out that everything was pretty good, so I put it back together again.”

Dust

Barry and I were on the side of the road talking about the Bentley when photographer Craig Watson commented about the dust on the car and asked if anyone had a chamois.

“It’s only a little bit of dust.” Barry responded. “That’s nothing to what it looks like sometimes. We use the car as much as we can. One trip was from Perth to Darwin which is about 2,500 miles each way along the coast in Western Australia. It’s through iron ore country and you should have seen the Bentley then as it was hard to see the blue paint through the red dust. It’s got no air cleaners for a start so we did try to avoid dirt roads, but that wasn’t always possible.

“One of the things that’s really important to me is the driving experience. It’s a challenge to drive and when you drive it well, it’s immensely satisfying. It doesn’t pay to get complacent, because as soon as you do, that’s when you start to muck things up. Simply put, if you drive it well, it performs very well. Without any doubt it’s the best car I have ever owned because of what it can do.

“The gearchange is without doubt a challenge, but over time it’s something to be mastered so that it’s extremely enjoyable. It’s all about timing, and when you come to a corner and do a nice change down to third and away you go…it’s so satisfying!

“As said, we use the car frequently,” Barry added. “In addition to driving on the road there has been runs at Phillip Island, Rob Roy Hillclimb, Sandown and support events to the Australian Grand Prix in Melbourne. The car is surprisingly quick for what it is. For instance, we took it in the 2000 Targa Tasmania and it was quicker than many of the TRs and MGs through the street circuits. It’s not a light car to drive and it’s good exercise when you have to do a U-turn. You don’t have to go to a gym when you drive the car, but having said that before Targa Tasmania I did an eight-week course in upper body strength that certainly helped, as I could do the long stages throughout the event. We also take the car on touring events organized by the Bentley Drivers Club of Australia, such as the run to Darwin.

“The club is a separate club to the one in the UK, but is for W.O.s. We took the car to England in 2010 and did a four-week rally around England, Scotland and Wales. That was organized by the British Bentley Drivers Club and there were around 50 cars driving completely around the UK except for Northern Ireland. It was fantastic, and perhaps the best part was driving through the middle of London, up to the Savoy Hotel where we stayed. You do not see many W.O. Bentleys in the middle of London, and it created quite a bit of interest. Yes, I did pay my £10 congestion tax.

“In early 2018, we are taking the car to the U.S. We have a member of the club who spends half the year in Canada and the other in Australia, so we have organized an event called the Can-Am Rally. We start in San Francisco and head east to the Rockies before turning toward Canada and then back to Vancouver. Again, it’s W.O.s only, and there are 14 taking part, of which 10 are from Australia and the others from New Zealand, England and Switzerland. Before all that I am doing the California Mille in the Bentley.

“It’s the sort of car that you can take part in high-speed long-distance rallies, to circuit racing to hillclimbs. A few years back we were in Western Australia and it turns out that Bentley drivers are well connected, so much so that the local police kindly closed a public road for us so we could do speed trials. The police also provided a radar gun to check our speed and I’m pleased to say that we managed to set the fastest time of 112 mph, complete with my wife on board. The noise was so incredible that the police officer thought it was a Spitfire going past so I had to take him for a run.”

Then photographer Craig asked about the roof and if it could be put up. “Never done it!” came Barry’s answer. “In my whole period of ownership I have never put the roof up.” Then he asked about the Porsche silhouettes on the aeroscreen. “They were given out at a Grand Prix Rally to anyone who passed a Porsche. I was pleased that I was presented with two.”

Challenge

As Barry said, driving his Bentley Speed Six was a challenge. Interestingly, there is no driver’s door on the right side, so it’s a matter of getting in on the left and sliding across. There is no gearstick to impede your entry as that’s on the right-hand side between your right knee and bodywork.

Once out on the open road keeping to the speed limit in fourth was immensely satisfying. After changing down a few times to third, all I can say was that I am pleased that the gears themselves are of a size to handle some less than deft handling. The often-used saying, “it’s a good thing that all the gears are in a box” couldn’t be more appropriate, as changing back from fourth to third needs plenty of practice and almost infinite patience. At one stage, I thought I would try something different and went from fourth to second. Straight in and with the immense torque of the engine it didn’t bother it in the slightest. Probably not something that Barnato would have done, but I enjoyed it.

There is lots to do when driving the Speed Six as there is not only the right gearshift, but there are also three levers on the steering wheel boss to keep you occupied. Mixture, throttle and ignition are embossed on an alloy ring, but Barry tells me that as the engine is warm, the only thing I really need to think about is to advance or retard the ignition. Instantly forgot of course, but with a little moving of the lever it certainly makes a difference when accelerating.

Then there is the steering, which is understandably heavy. Perhaps I should have concentrated a little on my upper body strength too? As expected it’s reasonably light when moving along, but super heavy when doing anything like a tight 47-point turn, and then there is reverse gear to find. However, it all comes together, especially when it comes to a stop. Once again the brakes are heavy, but very purposeful and I felt my reassurance increasing every time I pushed the pedal.

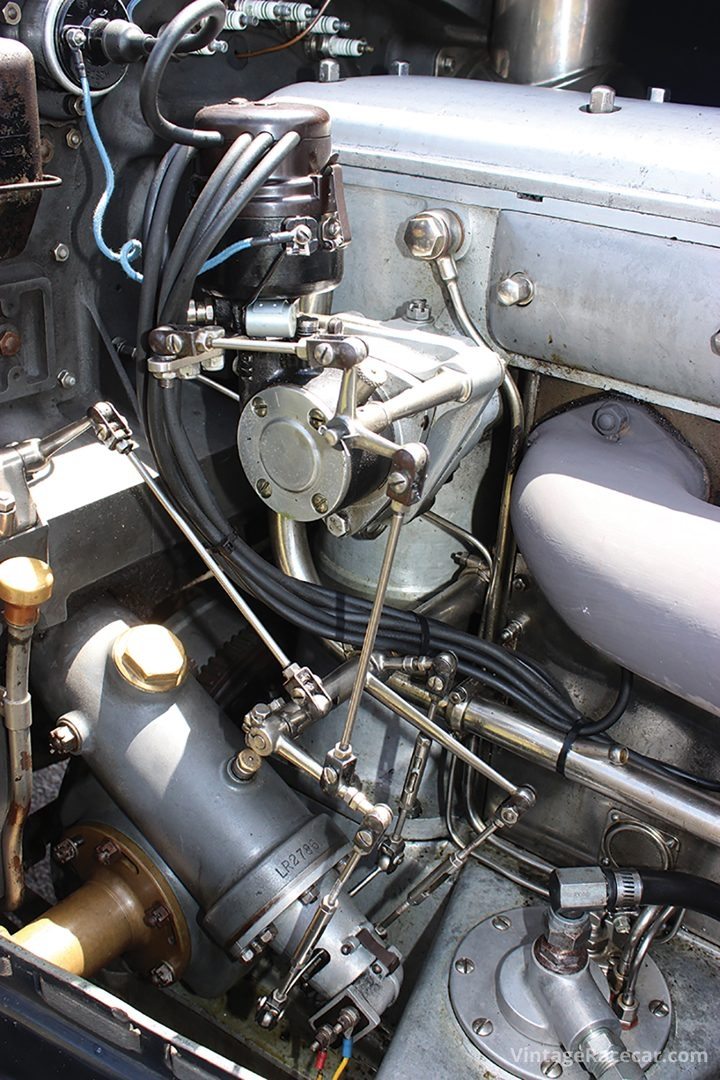

Under the bonnet is a delight and that engine seems to go on forever. At first glance, it looks like a straight-eight as the cam cover is about a third longer than the engine itself. Nothing over complicated, but there is so much of it. For instance, at the back of the engine is what looks to be a large diameter vertical tube that covers the drive for the single overhead camshaft. With other cars of the period, this may be by way of a driven shaft or even gears, but not with the Bentley Speed Six engine.

I asked Barry how it worked and he said the easiest way to comprehend it is to think about the drive or coupling rods on a steam locomotive. With the Bentley engine there are three rods connected to individual eccentric circular lobes on the camshaft and also to similar cams on a geared shaft/wheel that’s meshed with a gear on the rear of the crankshaft. Surely an ingenious design that Bentley brought with him from his locomotive apprenticeship.

Six-cylinders, four valves per cylinder, Electron alloy castings and 12 spark plugs. The Bentley engine is fitted with six spark plugs on one side of the engine and six on the other. On the driver’s side, there is a distributor and coil, while on the passenger side the plugs are fired by a magneto.

Understandably, Barry has added a couple of modern touches like an electric fuel pump and spin-on oil filter. However, the original Autovac fuel feed system and filtering system are still in place, albeit disconnected.

Barry Batagol’s 1930 Bentley Speed Six? A magnificent motor car that was built to be driven in the W.O. vein—like a sports car. Many thanks to Barry for allowing us to truly enjoy the experience.

Specifications

Body: Various over wooden frame

Chassis: Steel C section

Wheelbase: 11ft 2 ½ in, 11ft 8 ½ in and 12ft 8 ½ in

Track: Front & Rear 4ft 6in

Length: 15ft 7in and 16ft 7in

Width: 5ft 8 ½ in

Weight: 3,587 pounds or 3,696 pounds

Suspension: Front: Semi-elliptic leaf springs with friction dampers, Rear: Semi-elliptic leaf springs with friction dampers. Hydraulic dampers after 1929.

Engine: Six-cylinder overhead camshaft with four valves per cylinder

Displacement: 6,597cc (100mm x 140mm)

Induction: Twin SU HVG5 carburetors

Power: 1929: 160bhp at 3,500 rpm. 1930: 180bhp at 3,500rpm

Transmission: Four-speed “crash” gearbox and reverse

Brakes: Rod-operated drum-type brakes on all four wheels with Dewandre vacuum servo.

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.