Sexual debauchery, a regime’s imminent downfall and a kidnapping fit for a gentleman were some of the highlights of the 1958 Grand Prix of Cuba for sports cars. Racing during the fifties was noted for some remarkable events. The horrific 1955 Le Mans when almost 100 spectators lost their lives comes to mind. And how about Juan Manuel Fangio’s magnificent drive at the 1957 Nürburgring when he defeated the best in Formula One with an outdated car, winning his fifth World Championship? But maybe this one takes the cake.

The race itself only lasted six laps. Some of the best drivers of the day were on hand. Among the entrants was the Cuban dictator’s chauffeur! Huge crowds watched during the two days of practice and qualifying. The day before the green flag dropped, Fangio was kidnapped! Prize and appearance money was paid with cash in paper sacks. These are only a few of the bizarre goings on.

The setting was something out of a Hollywood movie. Cuba had been a democratic country until 1952 when President Fulgencio Batista took power by dissolving the elected legislature and suspending the constitution. Havana became a hotbed of gambling, prostitution, cheap liquor and great cigars. American mobster Meyer Lansky ran almost everything. The casinos were making more money than those in Las Vegas. It was a common sight to see Hollywood stars and Wall Street high rollers frolicking among gangsters.

Meanwhile, a band of militants in Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains—led by Fidel Castro and his brother Raul—was fomenting revolution. When the race took place in February, Fidel Castro and his “26th of July Revolutionary Movement” were well on their way to deposing Batista and taking over.

Bruce Kessler, who drove in the race, told me recently that, “Havana was a really beautiful city. It was a great place to have fun. There was entertainment for every taste including sex shows, some involving women and animals.

Beards were the badge of the rebels. Nobody else in Havana wore one. Jo Bonnier and his friends, Ulf Norrinder and Hans Tanner however, sported beards. Apparently being mistaken for some of Castro’s revolutionaries, they were arrested. Kessler got a call in the middle of the night from Jo, “Bruce, I’m in jail, come and get me.”

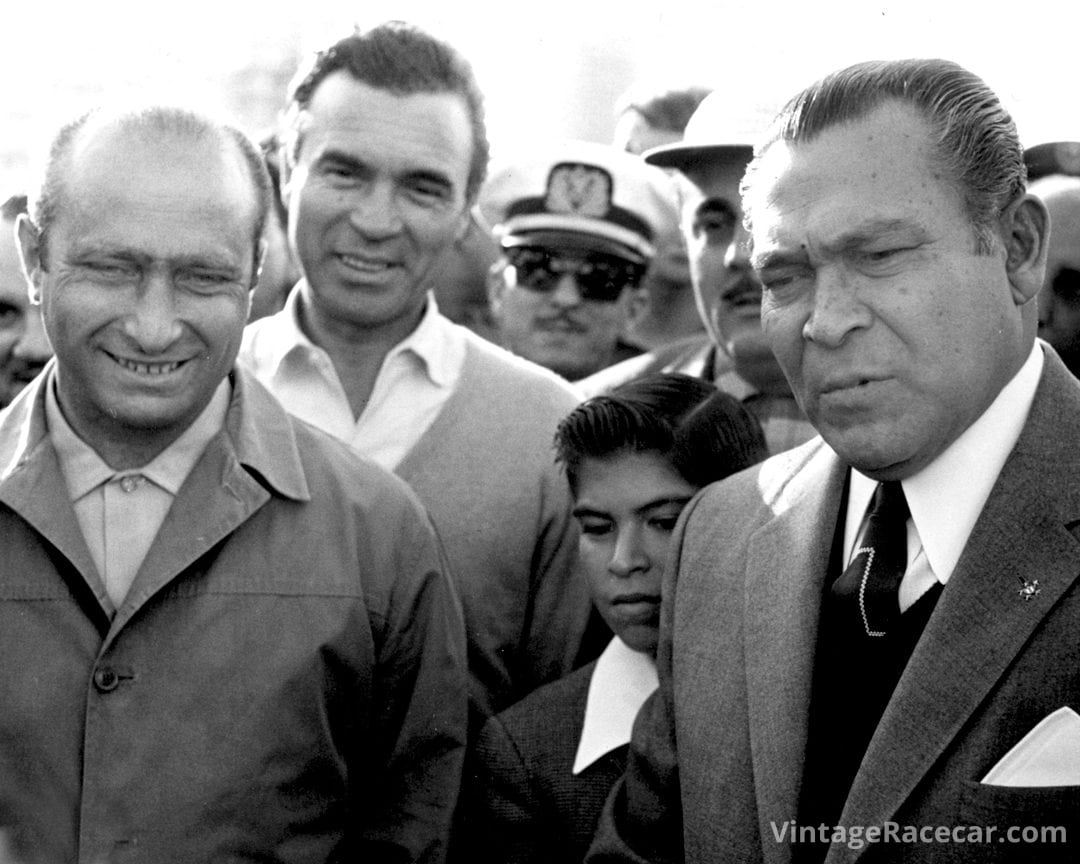

Foremost among the entrants was Fangio, who was to drive a 4.7-liter Maserati for Temple Buell. Stirling Moss was in a 4.1 Ferrari. Phil Hill, Masten Gregory, Wolfgang von Trips, Ed Crawford, Porfirio Rubirosa, Paul O’Shea, Boris Said (the father) and Bruce Kessler were also in Ferraris. Carroll Shelby, Harry Schell, Jo Bonnier, Jean Behra, Jim Kimberly, Giorgio Scarlatti and Maurice Trintignant were in Maseratis. How’s that for a lineup?

The 3.1-mile course was laid out through the city streets of Havana. The longest straight was the spectacular seafront boulevard, the Malecon, where cars could reach 160 miles an hour. The edges of much of the circuit had high sidewalks and deep gutters. There was absolutely no protection for the dense crowds, not even hay bales or sandbags. It was a disaster waiting to happen.

Leading up to the Grand Prix were two days of practice and qualifying. Kessler remembers that Fangio “would pass me like I was standing still. He threw that big car around like a go-kart. It was something to watch. When we came to the turn onto the Malecon, there were girls on the balconies throwing flowers. I almost crashed looking at them.”

The day before the race, Fangio was chatting with friends in the lobby of his Havana hotel. A bearded young man, Manuel Uziel, burst in and, pointing a 45 revolver at Fangio, said, “In the name of the 26th of July Movement, follow me.” Outside, four more bearded men with automatic weapons prevented anyone from interfering. Forced into a waiting car and driven off, Fangio was told he would not be allowed to compete in the Grand Prix, but that afterward, he would be released. The purpose of the kidnapping, he was told, was to focus world attention on Castro’s cause. Later, Fangio said that during his incarceration, he was treated with courtesy.

Apparently, the kidnappers also planned to nab Stirling Moss. Carroll Shelby was overheard telling Moss, “I just heard Fangio has been kidnapped and I think you’ll be next.” Apparently, Fangio talked them out of it by telling them that Stirling was on his honeymoon (Stirling and Katie Molson had married the previous October, but were not then on their honeymoon.) and that it would be discourteous to upset his new wife. Nevertheless, after hearing of Fangio’s plight, Moss, according to Kessler, was “just going ballistic.”

After the abduction, each driver was assigned a bodyguard plus there were guards in the hotel hallways. Kessler remembers a knocking on his door in the middle of the night before the race. When he opened it, he noticed all the guards were asleep. There was a girl at the door sent by the race organizers. She came in and stripped off all her clothes. “That took my mind off the danger of being kidnapped.” Ronny Burns (George Burns’s son) who was performing on the Burns & Allen show at the time, called Bruce and said he would charter a plane and come to get Bruce out of there. Who knows what the Los Angeles newspapers were reporting! Bruce replied he was okay and actually having fun (naked girl?), that he wasn’t being held at gunpoint and would tell Ronny all about it when he got home.

Photo: Bernard Cahier, courtesy Road & Track

The morning of the race, all the drivers were invited to Batista’s palace for breakfast, but none showed up. Everyone was nervous about the kidnapping. The imprisoned Fangio was given a large breakfast followed by what he later described as an excellent lunch in the company of three young women, one Fangio later described as wearing a “sensationally low-cut dress.” He was allowed to listen to the race on the radio and learned that Maurice Trintignant had replaced him in the Maserati.

A huge crowd, estimated at more than 200,000, had gathered for the 2:00 p.m. scheduled starting time. All the drivers got in their cars and the starter whirled his flag signaling them to start their engines. But then, delay after delay took place and engines started to overheat. There was an erroneous police report that Fangio had been released. The start was held up in the hope that he might appear. It wasn’t until an hour and a half later that the green flag finally dropped sending the 27 entrants off for the scheduled 90 laps.

Masten Gregory led off, but during the first lap, Stirling got by with Carroll Shelby in a close 3rd. On the sixth lap, using what Shelby later described as “some pretty daring driving,” Gregory retook the lead.

A Cuban amateur, Armando Cifuentes in a 2-liter Ferrari, hit an oil slick dumped on the course from Roberto Mieres’s Porsche, and went into the thickly packed crowd killing 6 and injuring another 30. Cifuentes, a local businessman, who had not practiced in the Ferrari, was the relief driver for another Cuban amateur who at the last minute decided not to race. Red flags popped out and spectators started to run into the streets. Some machine-gun fire was heard, apparently fired in the air in an effort to clear the course.

When the red flags were displayed, because of the confusion, rather than stopping in place, Masten, followed closely by Moss and all the rest, drove slowly back toward Start/Finish. Technically, they were still racing because of an FIA rule that a red flag was valid only when displayed by the Clerk of the Course at Start/Finish. Another rule was that a race is bona fide after the completion of at least five laps. Just before Gregory got to Start/Finish, Moss sped up and passed him, thus being scored the winner by one second.

It was announced on the PA that there would be a later restart. Nevertheless, in an impromptu paddock meeting, the drivers voted not to continue. Masten said he was going to protest Stirling who retorted, “Don’t be bloody silly, Gregory, you ought to read the rules.” Stirling pointed out that if Masten actually protested, the prize money would be placed in escrow until the matter was resolved. If Castro took power in the meantime, neither would be likely to get anything. So Stirling suggested, “It’s $10,000 1st-place money and $7,000 for 2nd, so let’s pool it and split it.”

Gunfire could be heard in the paddock after the race. There was even a rumor that Castro’s rebels had dumped oil on the course in order to sabotage the event. As soon as the drivers could leave, Stirling got Katie, and because the passenger seat was covered by a metal tonneau, put her on the headrest of his racecar, and drove directly to the airport.

That evening, Fangio, still in captivity, was treated to a jovial dinner with a small group of bearded revolutionaries—some even asked for his autograph. At about 10:00 p.m. that night, he was delivered to the Argentine embassy accompanied right to the door by one of the kidnappers who said, “You are free, Señor. Please excuse us for having inconvenienced you.”

Photo: Bernard Cahier, courtesy Road & Track

The plan for the next day was for all the drivers to go to the Sports Center, a large building in Havana. There they were to receive reimbursement for expenses, as well as prize and appearance money. Everyone except Stirling showed up. When all were assembled in a large room, there was a commotion and Fangio appeared. He described (in Spanish with a simultaneous English translation) what had happened to him.

Arriving home, Phil Hill summed up the consensus among the participants, “I think we were all glad to get out of there, especially Fangio.” Almost a year to the day after the race, Castro succeeded of course, and remains in power at this writing.

The next Grand Prix of Cuba for sports cars took place in 1960, a year after Fidel had taken power. The course was moved out of the city to the Libertad Airport. Allen Markelson entered in his Ferrari Testa Rossa. He remembers that “There were groups of kids about four-and-a-half-feet tall packing 45s, walking around the paddock and guys with AK47s in the pits. At a luncheon, I sat across from Castro, who spoke good English. When a waiter dropped a large aluminum tray making a sound like a shot, Castro turned white. It’s a moment I won’t forget.”

Twenty-three years later, 70-year-old Juan Fangio, then head of Mercedes-Benz in Argentina, returned to Havana in an effort to sell 1,300 trucks to the Cuban government. Waiting at the airport to greet Fangio was Arnaldo Rodrigues—once a bearded militant—now an official in the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Commerce. Rodrigues remarked that “During the kidnapping, I remember he (Fangio) had nerves of steel, great serenity.” While at a luncheon, Fangio, who was treated as a guest of the state, was seated with Faustino Perez, who had been the leader of the kidnappers. The UPI story reporting Fangio’s visit failed to mention if he was successful in selling the trucks to Castro.