Tony Valadez’ elegant 1939 Pontiac convertible is everything later Pontiac muscle cars are not. The later cars were brash, flashy and fast. Tony’s vintage Pontiac is none of these things. Instead it is handsome and understated. It is also roomy, comfortable, smooth, quiet, durable and dependable. And when I say durable, consider this, Valadez’ Deluxe Six 26th series Pontiac has been around for nearly 80 years and is still on the road, and still a styling knock out.

Tony purchased the car, already meticulously restored, from an extensive, local Pontiac collection that was being sold off. He was a little concerned about how his wife might receive the news, but she loves their classic drop-top Poncho, and enjoys the show circuit as much as Tony does.

I open the big, broad door and slide onto the sofa-like, wine dark leather bench seat, while our photographer climbs into one of the sidesaddle jump seats in back. In front, there is ample room in every direction. I can even wear my favorite fedora at a jaunty angle without bumping the convertible top, and I am over six feet tall.

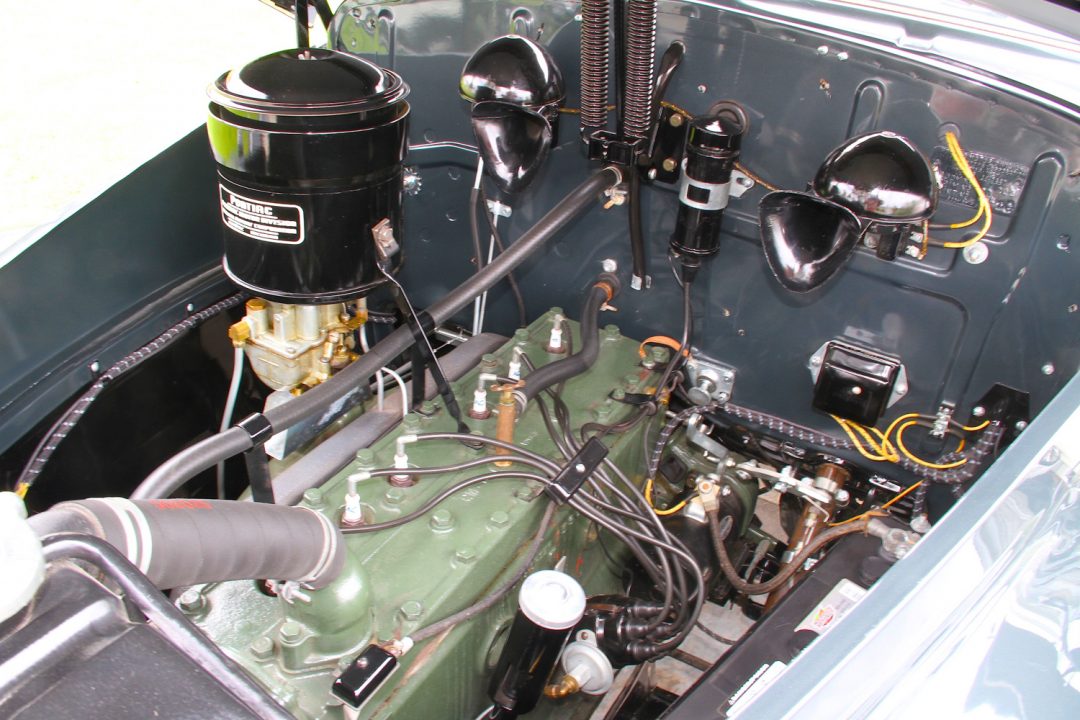

I turn the key, step on the starter pedal and the 222 cubic-inch, flathead six turns over indolently thanks to its six-volt electrical system. It takes a revolution or two in order to get fuel up to the carburetor before coming to life. There is a slight unevenness as the engine warms, and then it settles into near totally smooth silence.

This car is fully equipped, with a deluxe pushbutton radio, heater, banjo steering wheel for rough roads, whitewalls, and even a deluxe oil bath air filter. It also has the three-way headlights with which, on the right setting, you can keep an eye out for ditches beside the road, as well as obstacles straight ahead. Also, to top it all off, Tony’s car has the extra-cost fancy hubcaps and beauty rings, which pretty much exhausts the accessory list for the model year.

There is a full array of analog instruments in the handsome wood-grained metal dash, and they are large and easy to read. The dancing oil pressure, temperature and ammeter gauge needles tell me that nothing is amiss, and the engine is warming nicely, so I pull the three-on-the-tree stick shift into low and we slip away at a dignified pace.

Incidentally, 1939 was the first year for column shift on most American brands, but Pontiac had it in 1938 as an extra cost option for the more safety conscious. Changing gears is not quite as quick and precise as the old floor shift, but the arrangement is safer in an accident, especially with a third person sitting in the middle with the tall, intrusive floor shifters of the era.

Pontiac’s Series 26 Deluxe 120 was offered in several “Silver Streak” body styles. There was a four-door touring sedan, a two-door touring sedan and a two-door business coupe, as well as a sport coupe with jump seats in back, and Tony’s convertible coupe. Pricing ranged from $815 to about $1,000 depending on model and accessories, and there were a total of 53,830 examples produced during the 1939 production run. Of that, few are left, especially convertibles.

First gear has that familiar pre-war Pontiac non-synchromesh whine, but when I shift into second the transmission goes quiet. Acceleration is surprisingly good considering that this deluxe model has the bigger B.O.P. body used by Buick and Oldsmobile as well. These more expensive 120-inch (hence the 120 designation) wheelbase Pontiacs were marketed as an upgrade from the less expensive Quality Six line, which sported the smaller body also used for Chevrolets. And both brands were mounted on a lighter 115-inch wheelbase chassis.

The good starting acceleration is partly because the engine in Valadez’ Pontiac was designed to produce abundant bottom-end torque and cruise at low rpms. Why so, you might ask? Well, for one thing, most people didn’t seek high-strung, high-speed performance in 1939. Cars were expensive, and maintenance was too, so people wanted cars that did not need frequent attention other than the standard routine servicing every thousand miles.

Besides, there was little or no need for speed. Highway 66 was only paved completely for its whole length from Chicago to Los Angeles beginning that year; and the first freeway in the United States was opened in Pasadena, California, in 1940, with a speed limit of 45 miles per hour. That was a nice cruising speed for this as well as most other contemporary cars, many of which had a red band painted on the speedometer to show you when you were above 50 miles an hour.

Overall acceleration in Tony’s Pontiac is pretty good by today’s standards, but not tire scorching, due to the car’s low (numerically high) differential gearing. However, because of that the engine starts to work pretty hard above 50 miles per hour. Steering is light thanks to the big steering wheel and the newly engineered steering system that was continued all the way into the 1990s for Pontiac. The car rides very smoothly too, thanks to its specially designed Duflex rear springs; and it corners with only modest body lean thanks to the front sway bar that Pontiac introduced that year.

In the 1930s it was standard wisdom that greater piston travel in the engine meant greater wear, which meant more frequent overhauls, so most American car motors were designed with longer strokes in order to produce abundant low and mid-range torque to keep the rpm down. In fact, it worked so well that around town many people never pushed their cars much over 1,000 rpm, and never shifted into high gear for in-town driving.

Think about it this way: For the engine to do one revolution, each piston must go up and back one time. And if the distance it must travel just one way is four inches (the stroke of our 1939 Pontiac) that means the piston has to travel a total of eight inches every time the engine turns over. If you multiply that eight inches times 3,000 rpm that tells you each piston must travel 24,000 inches, or 2,000 feet everyminuteat 3,000 rpm! However, if the engine is turning at 1,000 rpm, each piston only has to travel 667 feet during that minute.

This low rpm, high torque, approach made for better fuel economy as well. Valadez’ Series 26 Deluxe convertible gets 21 plus miles per gallon on the highway even though it weighs 3,150 pounds, and it can easily cruise along at just over 2,000 rpm at 50 miles an hour in high gear. The little 222 cubic-inch six has a red line of, 3,600 rpm and makes a mere 85 horsepower, which means it wouldn’t compete well on today’s freeways, but as we said before, in the old days it didn’t make much sense to push a car that hard.

Another reason for keeping the revs down was because Pontiac’s— as well as Chevrolet’s —pistons were made of heavy cast iron, so they would stress the connecting rods to the breaking point if you over-revved the engine routinely. Cast iron pistons may sound like a disadvantage, but having the pistons made of the same durable metal and with the same expansion rate as the block meant that they could run them at tighter tolerances, making for less oil consumption, and silent operation. Also, Pontiac’s pistons wore like – you guessed it – iron – so overhauls were needed less frequently.

The valve train on Pontiac’s flatheads is mechanical rather than hydraulic, as was used on a few more expensive cars of the time, and it is simple, short and stout so it could last a long time and need only occasional adjustment as a result. Also, you didn’t have to worry as much about oil contamination with mechanical lifters as you did with hydraulic lifters at a time when most cars did not come with oil filters, though such accessories were available as an extra cost option.

Pontiac also had a full pressure oiling system, and used thin-shell insert bearings for extra durability, unlike Chevrolet who stuck with its old-style, primitive, splash oiling system and thick poured babbitt bearings into the early 1950s. Thin-shell insert bearings did not absorb contamination as well as thick babbitt bearings, but they were much easier to replace when worn.

One down-side of inline flatheads though, is that adjusting valves on them was a pain because you had to remove the front passenger-side wheel, take out the inner fender panel, and climb in under the front fender with the engine running and hot in order to do the deed. This was downright diabolical, but thankfully it didn’t have to be done often. On the other hand, overhead valve engines with push rods and rocker arms such as you found in Buicks and Chevrolets of the era were easier to adjust, but required frequent attention to keep them gapped properly.

Tony’s Pontiac adds up to an altogether elegant inexpensive sporty conveyance for the trips to church, Saturday shopping, and Sunday drives typical of the era. In those days, people rarely drove back and forth to work. If they lived in town they walked, or took a trolley, and if they lived in the country, they worked on the family farm.

Valadez’ Pontiac drop top met the transportation needs of the day with style. Of course, there were faster flashier cars back then, all the way up to 16-cylinder Cadillacs that could loaf along at 80 miles per hour, and 12-cylinder Packards that could stay with the Caddies if you were in that much of a hurry. But only a privileged few could afford such frivolous transportation as the depression was ending.

Yes, modern cars are faster, safer, and stop better than Tony’s 1939 Silver Streak, but none of them have the virtues his car does. And none of them can take you back to a less hurried time when getting there was half the fun. In fact, often as not, it was all of the fun. A nice Sunday drive in the country with the top down, with perhaps a stop for ice cream or a chocolate malt along the way was a wonderful way to spend the afternoon.

It would not be fair to a car built in 1939 to judge it by our get-there-get-there-get-there, stressed-out criteria today. Valadez’ period Poncho harks back to a time when we savored life more, and conspicuous consumption and unnecessarily complicated electronic furbelow didn’t exist to thwart you and cost you dearly when you least expected it.

If you needed to find a destination, you used a map, and it never failed you unless you spilled coffee on it. If you needed air, you merely opened the wind wing. And your ignition key was just that: A key. You could get a duplicate at the hardware store for 50 cents. Sure, you had to be facile enough to insert it into the starter switch, but that was fairly easy to master. However with today’s cars, if your electronic “key” fails, it may cost you 70 dollars to get it reprogrammed, and if you loose it, it could cost $500 to replace it!

Historically, Pontiac started out in 1924 as a less expensive companion make for Oakland, much like at different times the Marquette was a companion make for Buick, Viking was a companion make for Oldsmobile, and LaSalle was a companion make for Cadillac. None of the other GM sister cars were successful for the company in the long run, but the Pontiac was such good value for the money that it ended up consuming Oakland, its host, by 1932.

Decades later, Pontiac transformed itself into General Motors’ performance car and was dazzlingly successful in the 1960s and ’70s. But that was then. Unfortunately, you can’t buy a new Pontiac of any kind anymore. General Motors stopped making them in 2009, except for a final one produced in January 2010. It was a white G6 intended for fleet use. Sadly, Pontiac went out with a whimper, not a bang. No press was even present to record this sad turn of events.

We roll silently back to Tony’s house, waving to passers by. We say our goodbyes to he and his wife Doreen, and then climb into my hot Hyundai, only to discover that its GPS system has fallen silent. I can’t say I miss that punctilious female voice talking at me though.

It is now rush hour, which means we will spend the next 45 minutes hermetically sealed in our cocoon, in stop-and-go traffic, on a six-lane freeway trying to get home, nostalgically yearning for where we had been, and wishing we could have stayed longer.

SPECIFICATIONS

| Original Base Price | $850 – $1,000 |

| No. Produced | 53,830 |

| No. Doors | 2 |

| Model Number | 120 |

| Weight | 3,150 lbs |

| Wheelbase | 120 inches |

| Engine Type | 6 cylinder inline L-head |

| Displacement | 222.4 cu. in. |

| Bore & Stroke | 3 7/16 X 4 inches |

| Compression Ratio | 6.2 to 1 |

| Brake Horsepower | 85@3600 |

| Main Bearings | 4 |

| Valve Lifters | Mechanical |

| Lubrication | Pressure to all bearings |

| Tires | 6.50 X 16 Firestone whitewalls |