What’s the single most important component, for maximal performance, on a racecar? The engine? Suspension? In the grand scheme of things it’s probably the checkbook(!), but that’s really outside of the car. As odd as it may seem, I’ve come to the conclusion that the racing seat probably contributes more to the success or failure of any given racecar than any other piece of equipment.

Recently, I had the good fortune to get to test drive the fire-breathing, Quadrifoglio version of the Alfa Romeo Stelvio for a week. True, it is a street car, but with 500-plus horsepower and credentials as the SUV lap record holder at the Nürburgring, it’s not far off a racecar. But one of the many things that struck me about this extraordinary car was the driver’s seat, which not only looks like a racing seat, but felt like one as well. Firmly nestled and supported in the Stelvio’s suede-covered seat, as I carved my way through canyon roads, I had a moment of realization that the seat—and by association, my physical connection with the Stelvio—was a major contributor to my sense of the car’s performance and driving satisfaction. This was the spark, that started my mind sifting back through 20 years of testing racecars to recollect whether my physical connection with those cars, correlated with my master list of what I considered “the best” cars I’ve tested.

Now, you might read this and say, “Well sure, if I got to drive a Tyrrell Formula One car, it’d rate as one of the very best cars I’d driven too!” And, while at some level you have a good point(!), the truth is I’ve also driven some cars, which intellectually I knew should be some of the best driving cars I’ve ever driven, yet the nature of the driver’s seat made them anything but…at least in my feeble hands.

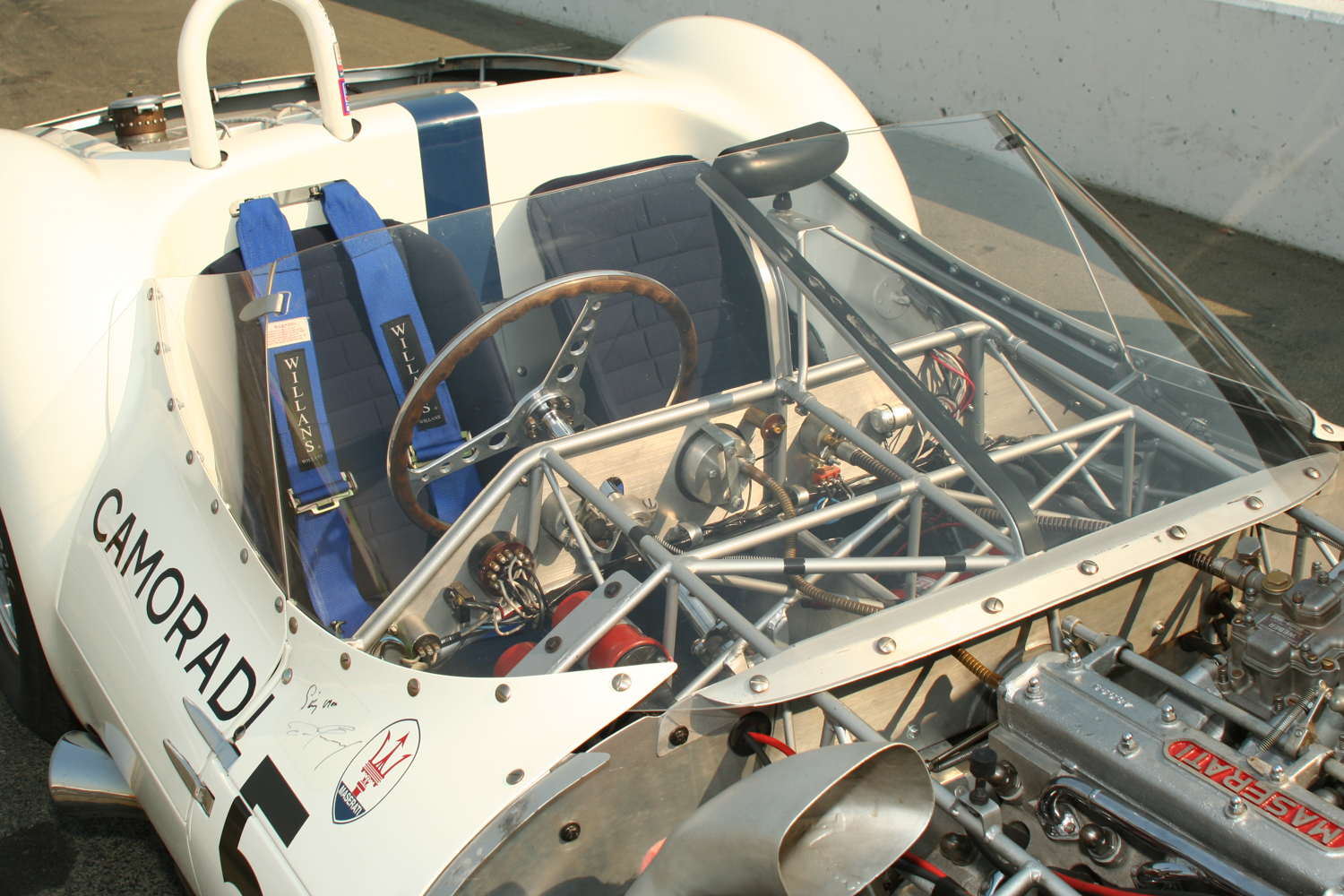

Case in point, the Maserati Birdcage. No question, one of the most significant, amazing historic racecars of all time. Widely regarded by drivers of the day as being balanced and oh-so-sweet-to drive. However, when I climbed behind the wheel of the 1960 Birdcage that Moss and Gurney drove to a famous win at the Nürburgring, I could not get comfortable in the car.

The seating position for my 6-foot frame was awkward and uncomfortable (how the hell did Dan drive this thing for 6 hours?!), the steering wheel felt to close, the pedals to far to the outside of the frame and the bubble-windshield was such that it was like looking through a funhouse mirror every time I had to peer through it to see the apex of a corner! Assessing the car’s individual elements (power, braking, handling) on their own merits, I knew this was in fact a great car, but due to my inability to comfortably connect with the car, it’s performance that day, and my perception of the experience, was nothing like it could have been. Had I enjoyed the same kind of connection with the Birdcage, that I did with the March, I’m sure the result would have been very different.

I also had a similar experience with the 1974 Shadow Can-Am car. Here was one of the truly great cars, from arguably one of the high points of the sport. The ultimate iteration of the Can-Am lineage, in its final year, the Shadow was an 800-horspower Championship winner. But it is here, where I think I most experienced the importance of the “Butt-Car interface.” I was sharing the car that weekend with noted historic hot-shoe Craig Bennett. Craig and I have a reasonably significant difference in height, but even more impactful was the fact that my freakishly long legs, probably ended somewhere above his waist! In order, to get me in the car so that my butt and hips were actually in the carand not on the car, we had to remove Craig’s custom seat and I had to belt into the bare tub.

This proved to be a pretty pragmatic solution as the overall position was good, my hips were down in the bottom of the tub, I could properly reach the pedals and if I sucked my gut in, I could use the belts without the team having to spend half an hour after each session to readjust then back and forth. However, floating around in the seat-well of the tub proved to be just that…floating around.

As I unleashed the full fury of those 800 ponies behind my head, and made my first left turn, my butt immediately sloshed from one side of the tub to the other! As I changed direction for the following right-hander, it was like a Yankee Clipper coming about on the high seas, my butt and entire upper body sloshed from one side of the seat-well to the other. In reality, I was probably only shifting a few inches from side to side, but the uncoupling of my butt from the car was remarkably distracting and unsettling. If your body is not completely in sync with what the car is doing, you essentially become separate entities…entangled separate entities, but separate entities nonetheless. And without that connection, I don’t care if you’re Mario Andretti or Fernando Alonso, you are not going to be able to get the best out of that car.

With all this said, I’m now firmly of the belief that a driver in an inferior car (but with the perfect connection with that car), will out perform the same driver in a technically better car, that has a horrible driver/car interface. And if this is true, then the oft-overlooked driver’s seat seems to me to arguably be the most important piece of performance equipment on any given racecar.

Turns out a car can be built for comfort AND built for speed.