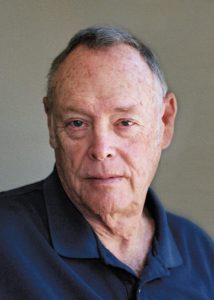

In the Western U.S. during the ’50s, there were a number of road-racing drivers who went on to international success in the following decade. Phil Hill, Carroll Shelby, and Dan Gurney come immediately to mind. However, if a single ’50s-era dominating figure had to be chosen, it would be Ken Miles, even though today he’s largely forgotten. A number of books have been written about Phil, Carroll, and Dan, but until recently, none about Ken. So, two years ago, I set out to rectify the situation and put together a book about Miles in my scrapbook format.

Doing my type of book is like taking a trip through time. Before I started on Ken—especially because of the relationship between the Miles’ and Evans’ families—I thought I knew as much as anyone did about him. But as I got into it, I discovered a lot more. For one thing, I learned about Ken’s service with the British Army during WWII. He landed with his tank group at Normandy two days after D-Day and fought across Europe until the victory.

Miles was a dominant figure during the ’50s, particularly in Southern California. He was not only one of the top road-racing pilots, but he also designed race courses, devised rules, set schedules, and helped govern the California Sports Car Club (in those days, independent from the Sports Car Club of America). In addition, he was a regular contributor to the monthly magazine, the Sports Car Journal.

Ken was imported from England, as it were, by John Beazley, then general manager of Gough Industries, an importer and distributor of British cars. Beazley needed a service manager and Miles fit the bill. Almost as soon as he got here, he started to race one of his employer’s production MGs. At the same time, he designed and started to construct an MG sports-racing car that later became known as the famous R-1. Its first race was at Pebble Beach in 1953, then the preeminent—and most hotly contested—Western States event. Ken won the main event for cars under 1,500-cc and then went on to win every single event he entered that year, a total of 10 races.

The next year, 1954, he sold R-1 to Cy Yedor and started to work on its successor, R-2. This second car was innovative for its time with a very lightweight frame constructed of small diameter tubes and an aerodynamic envelope body. In 1955, Miles won Pebble Beach in R-2, while Yedor came in 3rd with R-1. By then, Ken had become known as “Mr. MG.” During that same year, he was elected to the first of three terms as president of the California Sports Car Club. He designed three of the courses we used—Bakersfield, Pomona, and Paramount Ranch—and put together a program of almost a race every month. Undoubtedly, this contributed to the success of a number of our local drivers because they got more seat time than those less fortunate to have lived in other locales.

After the 1956 season, Ken left Gough Industries and went to work for John Von Neumann, the Western States’ VW-Porsche importer and distributor. Driving a Porsche Spyder for Von Neumann during 1956 and ’57, Miles finished 1st overall 16 times. Ken’s most successful time with Von Neumann, however, was at the wheel of a Cooper. With a Porsche, 4-cam racing engine in place of the usual Climax, Miles won seven out of nine races entered, including a 1st in class and 4th overall at Nassau against the best the world had to offer. The Porsche people in Germany (including competition director Huschke von Hanstein) became upset and forced Von Neumann to sell the Cooper.

As a result of a dispute with Von Neumann at the end of 1957, Ken joined the Otto Zipper-Bob Estes team with which he continued through 1966 driving Porsches. All in all with this marque, Miles achieved 38 1st-place finishes and almost always stood on the podium.

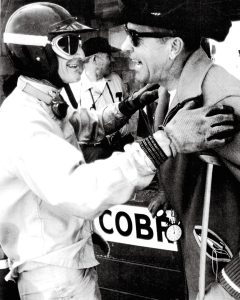

In 1963, Ken went to work with, and raced for, Carroll Shelby. Shelby credits Miles with making perhaps the most significant contribution toward the success of the Cobra and GT40 programs. According to Carroll, “Ken was world-class and the best test driver I ever knew. He was the heart and soul of our testing program.” Cobras were raced before Miles came on board, but with little success. Subsequently, they seldom lost. Shelby and Miles developed a very close relationship. Not long ago, Carroll told me that a day seldom goes by that he doesn’t think about Ken.

The year of the greatest successes and deepest tragedies was 1966. In those days, there was a triple-crown of road racing—the 24 Hours of Daytona, the 12 Hours of Sebring, and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Miles started out the year by winning both Daytona and Sebring with co-driver Lloyd Ruby. Then came Le Mans. For much of the race, the Shelby-entered GT40s of Ken Miles/Denny Hulme and Dan Gurney/Jerry Grant led. When the Gurney/Grant car blew a head gasket, the Bruce McLaren/Chris Amon GT40 inherited 2nd, some distance behind. At the last pit stop, Miles was informed that Henry Ford II—“The Deuce”—wanted a dead heat finish. So Miles slowed to wait for McLaren, who ended up being given the victory by the organizers because their car had started farther back on the grid, and therefore had traveled a farther distance in the same amount of time!

When I had dinner with Ken two months later, he seemed resigned to accepting the unacceptable. In those days, winning Le Mans for a sports car driver was equivalent to an Indianapolis victory for an American racer. Soon afterward, Ken got involved in testing the new Ford sports racer—the J-Car. At the time, I was in Mexico City on a photo assignment. At four in the morning on August 18, my dad called me at my hotel to tell me that Ken had been killed the previous day during a test at Riverside. Regretfully, I couldn’t make it back for the service. My dad, who had become Ken’s best friend, delivered the eulogy and ended it with the following quote from a poem: “He met with joy each fighting morn, full throated, drinking deep of life.”