Beverly Rae Kimes has been called the “First Lady of Automotive History” for good reason. She has written histories of many of the great cars of the 20th century. Her article titled “Auburn – From Runabout to Speedster,” published in Automobile Quarterly Volume V, Number 4, provides an interesting opinion about Auburn automobiles:

“The Auburn was always a bridesmaid. It was a family problem. Destined to be forever driven in the shadow of Duesenberg and Cord, the Auburn has never really come into its own. . . . It’s a pity, actually – for the bridesmaid was a lovely thing. Extremely good-looking, commendably fast, totally reliable – admirable qualities all. And what’s more, for the money, a prospective buyer couldn’t have asked for more than an Auburn. It simply wouldn’t have been available.”

“Extremely good looking?” Certainly. “Commendably fast?” Proven. “Totally reliable?” Truth. “Bridesmaid?” Not so to many owners. As for value, an Auburn was probably too good a value, an issue that helped lead to its demise.

Warning – an opinion statement from the author: the 1935 Auburn 851 that is the subject of this profile is the prettiest pre-WWII automobile I have had the honor of profiling. It starts with the color – Burnt Rust. A lovely color for this car. The grille is one of the best of all time. The lines, the details, the interior – just perfect for its time. Originally purchased as a parts car for a sedan, an earlier owner saw the benefit of restoring this incredible automobile. But that’s getting ahead of the story of Auburn.

Auburn Automobile Company

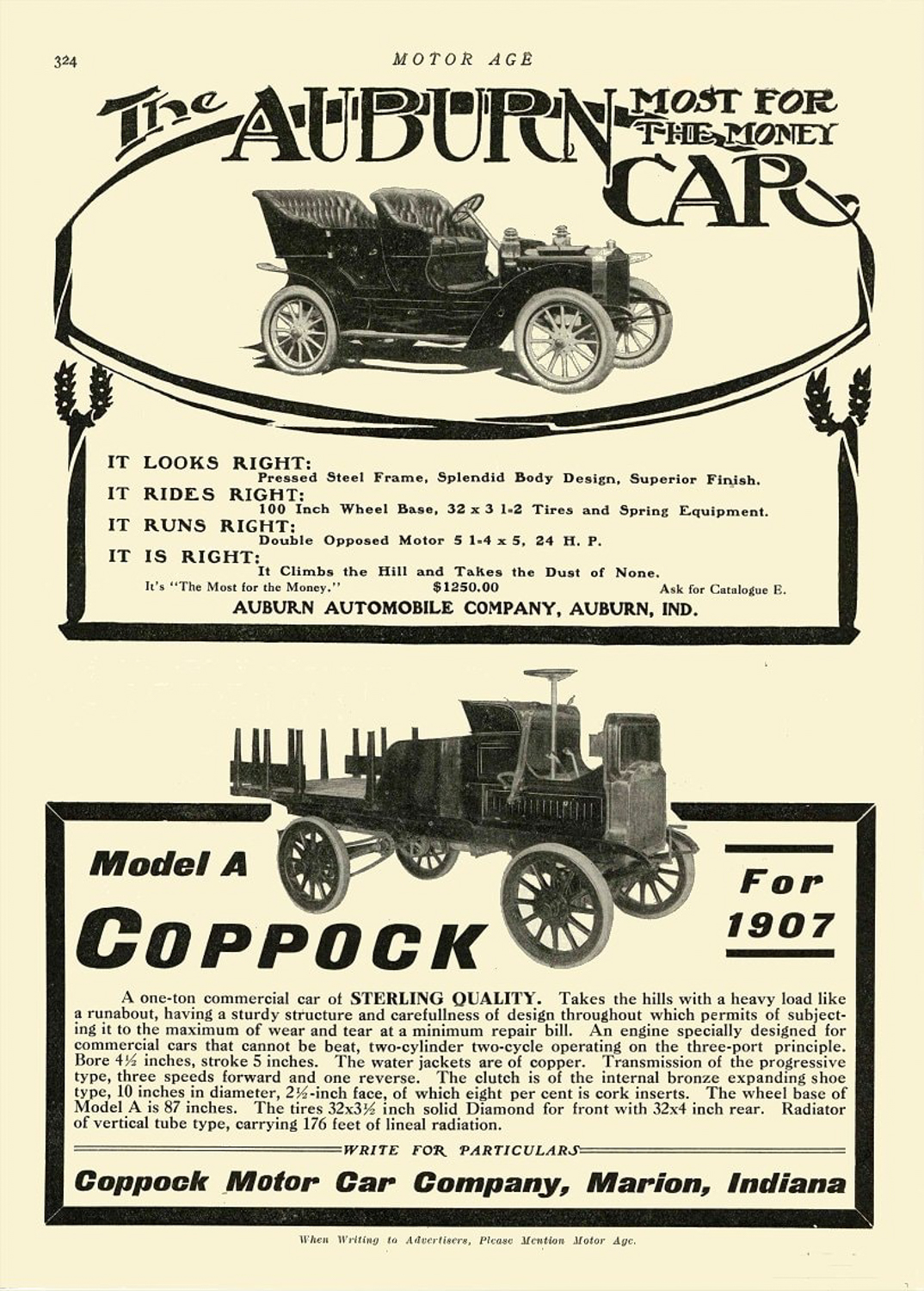

Charles Eckhart, a German immigrant, established the Eckhart Carriage Company in Auburn, Indiana, in 1874. Eckhart had worked for the Studebaker brothers as a wheelwright until he married and received an 80-acre farm as his new wife’s dowry. He traded that farm for a house and five acres in Auburn, where he established the Carriage Company. His three sons were taught part of the carriage business – Frank became a painter, Morris trained as a blacksmith and William was a trimmer. Frank and Morris took over the company when their father retired, but they had interests beyond building carriages. In 1900, they built their first automobile and established the Auburn Automobile Company. That car was a Runabout that used a single-cylinder engine producing 6 hp, used chain drive, was tiller steered, and had solid rubber tires. The car weighed 1150 pounds and sold for $800. A few or the early cars were hand built and sold, afterwhich the brothers began manufacturing their automobile in 1902. When the car was shown at the Chicago Auto Show, in 1903, the only improvement was pneumatic tires. Fifty of the cars were sold in 1904. A 12-hp, two-cylinder engine was produced in 1905. Named “Pleasure Car,” it could transport five adults with their luggage stored under the rear seat. The price of the car jumped to $1250.

Change came slowly during the next five years. A few options, such as windshield, top, and headlights, became standard equipment. The company created its first motto: “It Climbs the Hill and Takes the Dust of None.” In 1909, the company added a 4-cylinder. They used a Rutenber engine connected to a 2-speed planetary transmission driving the rear wheels via a center chain. Models offered were a touring car, roadster, and delivery wagon. Prices ranged from $1150 to $1650. A 41-hp, Rutenber 6-cylinder was used in 1912 for the company’s first 6-cylinder automobile, dubbed “The Satisfying Car.” There were three models, each using a different engine manufacturer for 1916 – Series 4-38 had a Rutenber engine, Series 6-38 used a Teeter, and Series 6-40 was powered by a Continental.

Although the company had been in business for nearly two decades, it still was not successful. In 1918, the company dropped its carriage production, and in 1919, the company was sold. A group of Chicago investors, headed by Ralph Austin Bard and including William Wrigley, Jr., of chewing gum fame. The group kept Morris Eckhart as the company president. Change came with the investors, and a much-improved automobile was produced in 1920. “The Beauty Six” was a very good-looking car with many optional innovations, such as steps instead of running boards, disc wheels, and front fender trunks. It was powered by a Continental “Red Seal” 6-cylinder engine producing just over 25 hp. Although it lacked the performance of some of its competition, it was a good looking car with a price of $2000, making it quite popular.

The Beauty Six helped, but the economy was not good. The Post-WWI recession was quickly over, but the transition from wartime production to peacetime was slow. Returning veterans found it difficult to get work, unemployment was up, and buying power was down. By early 1920, the economy was in a serious deflation – a recession so severe it was often called a depression. Although it only lasted 18 months, the effect on the automobile industry was significant. During the depression, auto production was down 60%. From 1919 to 1922, Auburn only produced 15,717 cars. Even by 1924, daily production was only 61 cars, and that was still above the demand. Then Cord arrived.

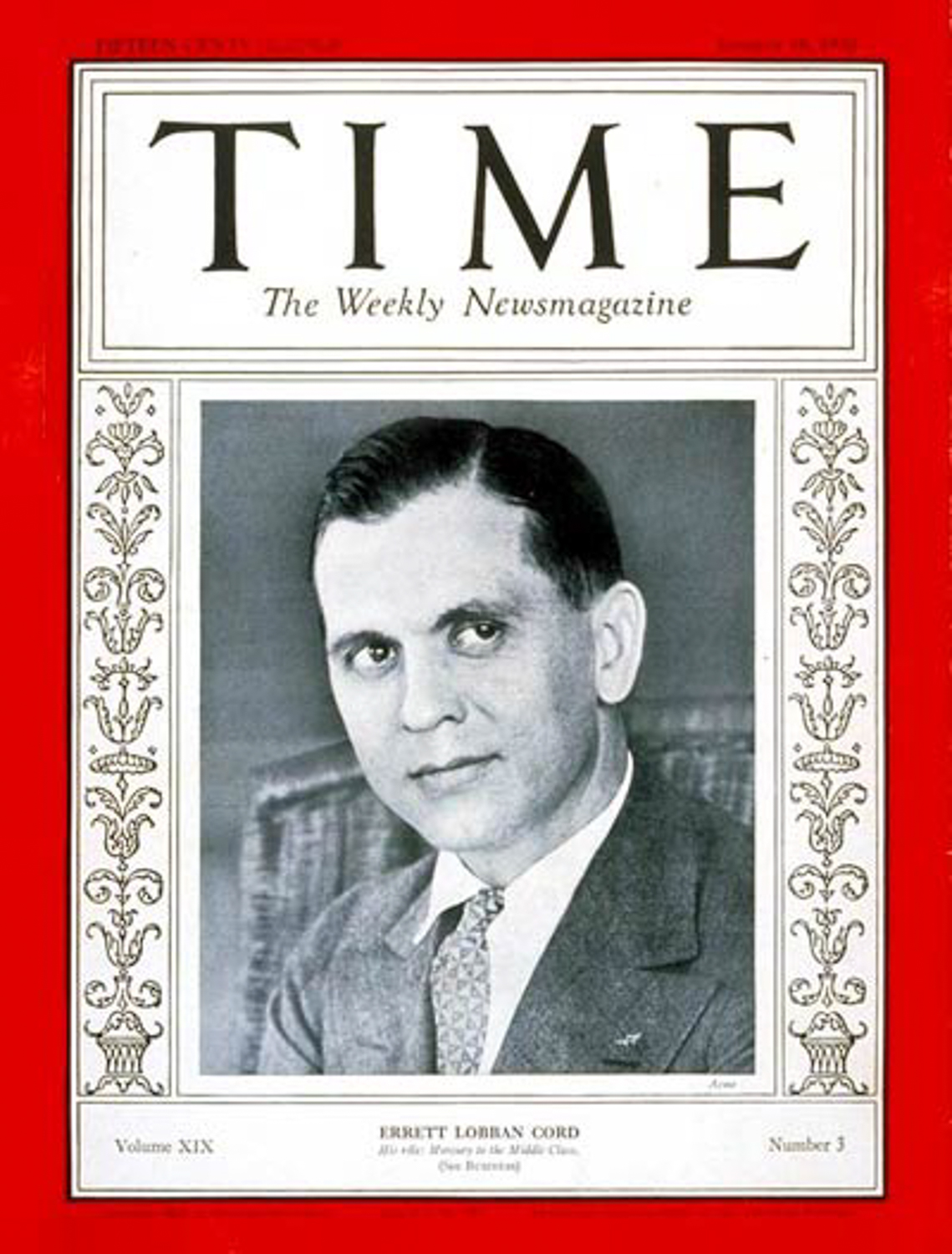

The Erret Lobban Cord Era

No story about Auburn can be told without Errett Lobban Cord. He was a super salesman. The “Times” called him both a “profane, bespeckled capitalist whose life has been a garage mechanic’s dream,” and “an astute, scheming, self-effacing business man who knows how and when grand parsnips can be found and buttered.” Cord was born in 1924 in Missouri, but his family moved to California where he finished high school and went into business for himself. He built racing bodies for Fords and was a racer on the west coast. He moved to Chicago in 1919 to work for the distributor of Moon cars and was so successful he acquired part of the business. More importantly, he saved $100,000, an amount that allowed him some independence to pursue other opportunities.

One of those opportunities was to become the General Manager of Auburn. Confident he could help Auburn become profitable, he took the job without pay. When he arrived at Auburn, there were about 700 touring cars sitting unsold. Cord directed that some nickel plating be added, had the cars repainted, and added some minor modifications. The direct result was that the cars sold and Auburn made $500,000. And that led to Cord being made a vice-president. Two years later, Cord would be Auburn’s president after doubling sales in 1925 and 1926. Profits were now on the order of a million dollars.

Changes were significant. The cars were all new. The 8-88, for example, went from a 276.1-cu.in., straight-eight producing 60 hp at 2850 rpm in 1925 to a 298.8 engine with 68 hp at 3000 rpm. The Chief Engineer, James Crawford, created a “twist proof” steel chassis and added semi-elliptic springs all around, hydraulic four-wheel brakes and Bijur automatic chassis lubrication all by 1928. McFarlan produced sexy coachwork, in 1927, with two-tone paint, flowing lines, and raked windshield. Auburns were now very European-looking for $1695. To sell the cars, Cord created a dealer network both inside and outside the U.S. Auburn became eleventh in exports of American automobiles.

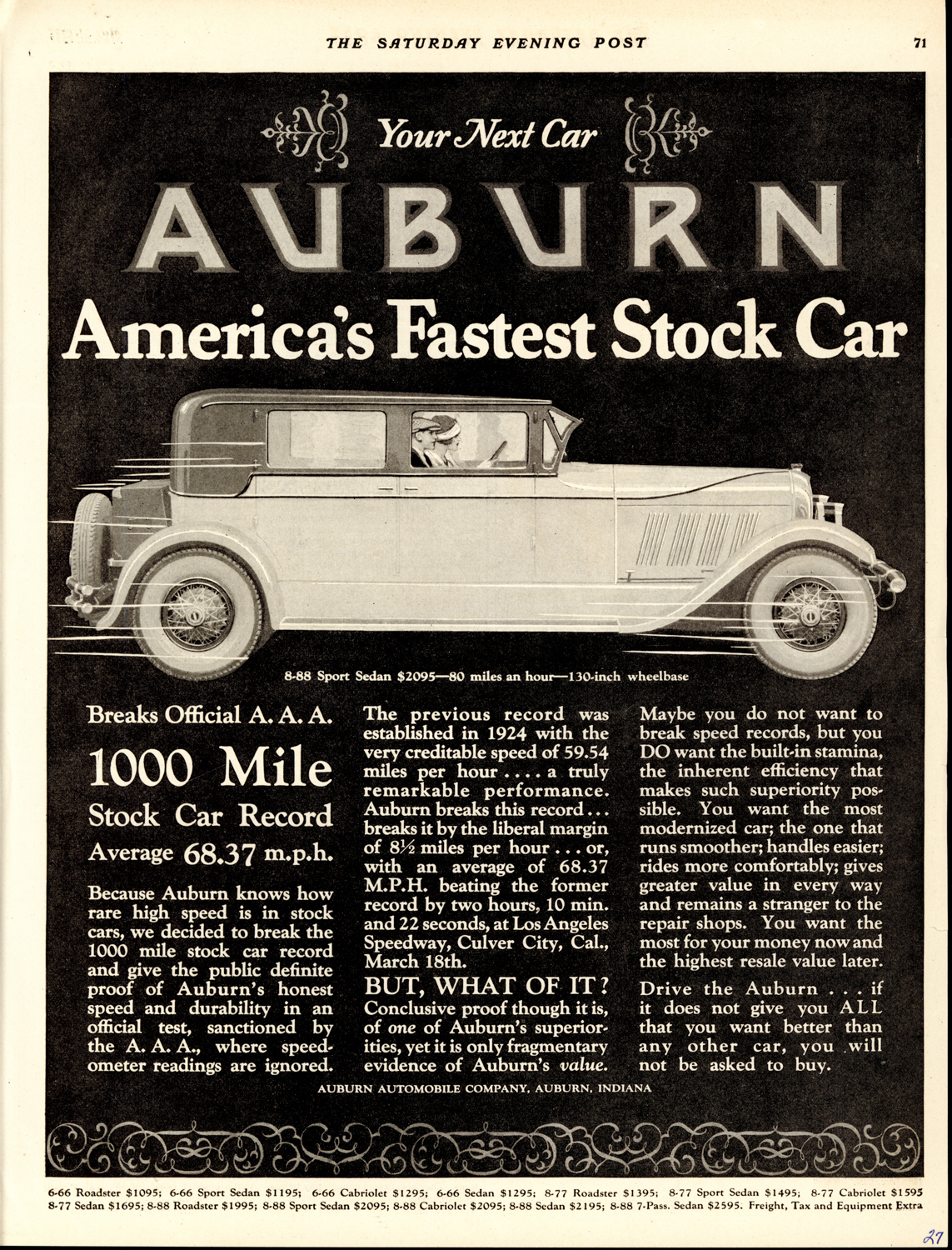

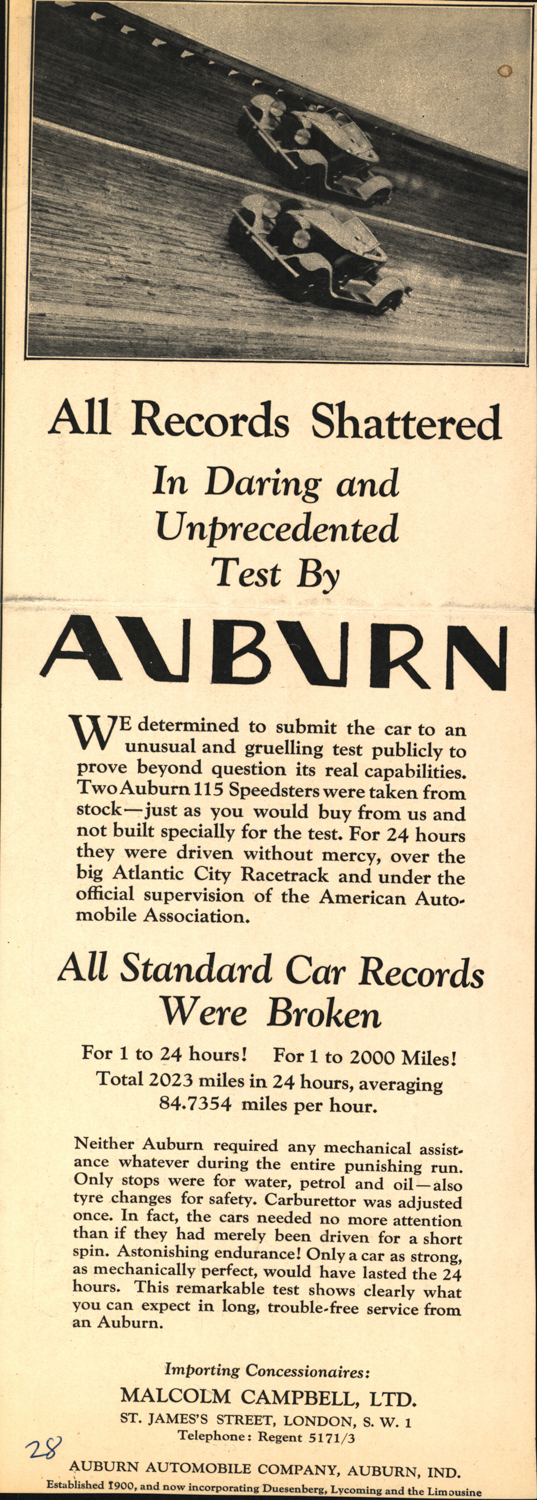

Cord saw motor racing as another way to market Auburns. Wade Morton took one to the Culver City Speedway in California, in March 1927, and established an average speed of 63.4 mph over 16 hours in a 1000-mile test. In May of that year, an Auburn finished less than one second behind a Stutz at the Atlantic City Speedway. At Rockingham Speedway in New Hampshire, Morton won a race on July 4that an average speed of 89.9 mph. Cord also sent two roadsters and a sedan back to the Atlantic City Speedway to set records from 5000 to 15,000 miles. Morton took one to Daytona and covered a mile at 108.46 mph. Late that year, an Auburn covered 2,033 miles in 24 hours at the Atlantic City Speedway at an average speed of 84.7 mph.

In September 1928, an Auburn ran Pike’s Peak in 21 minutes 45.40 seconds to take the Penrose Trophy. Auburn was being noticed. It was also being noticed for the Boattail Speedster, they called the “raciest coachwork available to the motorcar.” In addition to its distinctive Auburn downsweep hood molding, it had a steeply raked windshield, finely defined lines, and a golf bag locker.

A total of 22,000 Auburns were sold in 1929. Cord vigorously marketed the cars through the sales and dealership organization he had revamped. He was a believer in maintaining a shortage in the supplies of the cars, so he controlled production of Auburns and therefore demand always exceeded supply.

Cord had done very well since taking over Auburn. In June 1929, he created the Cord Corporation as a holding company for his acquisitions, which included Lycoming Motors, Ansted Engine Company, Central Manufacturing Company, and Duesenberg, in addition to Auburn. That same year, the Duesenberg Model J and the new front-wheel-drive Cords were introduced.

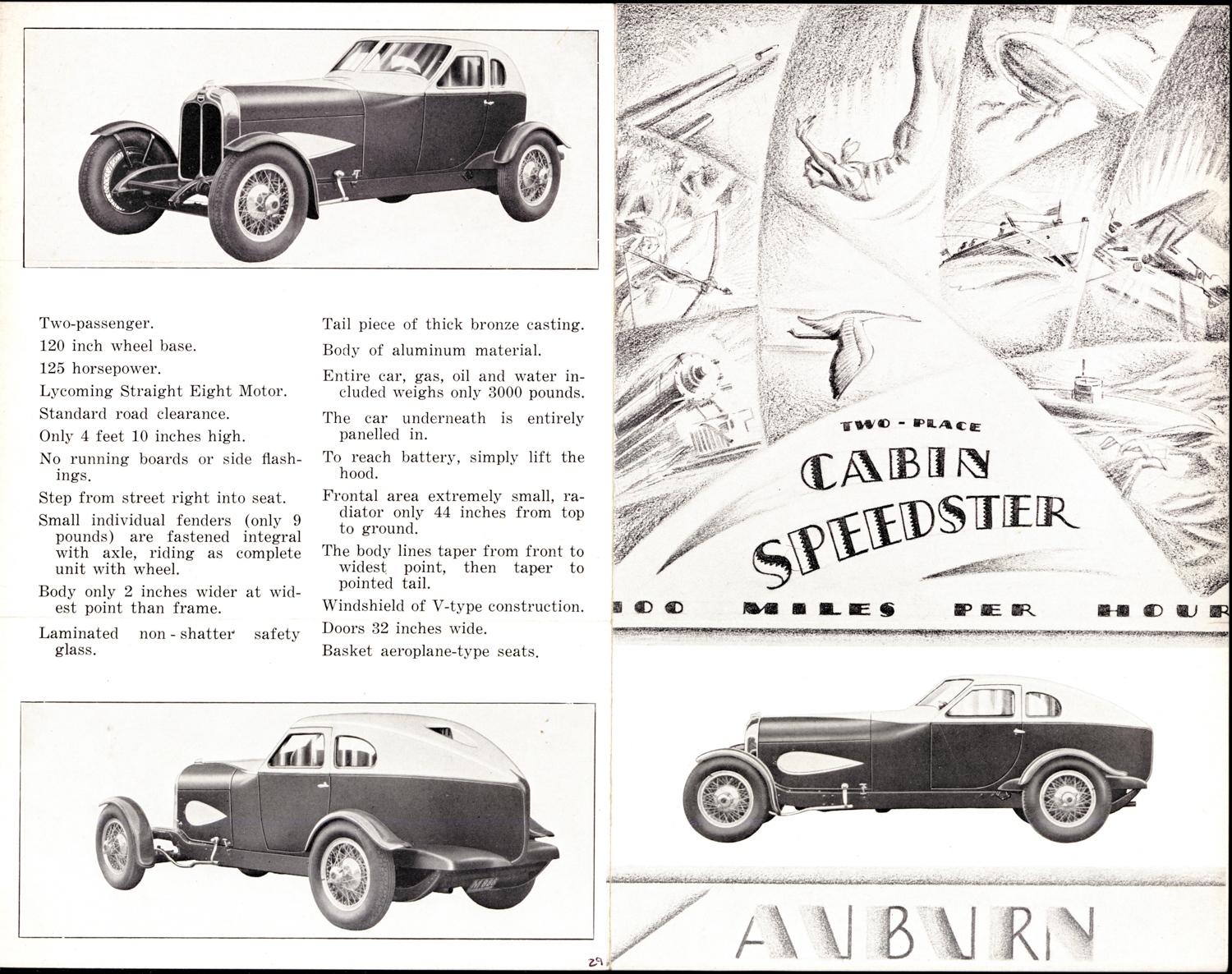

A particularly spectacular Auburn was introduced in 1929, the Cabin Speedster. Histories of the car suggest that there is some question about who designed the car, although the company’s description seems to make it clear: “a subtle compound of racing car and aeroplane, sky-styled, designed by the famous racing driver and aviator, Wade Morton.” What is known for sure is that the body was built by the Griswold Body Company, and the car was first shown at the 29thNational Automobile Show. The car was low and sleek. It was 44” at the radiator and only 58” at the roof. It had aluminum body panels and cycle fenders that moved with the wheels. At 3000 pounds, wet, it was not light, but it was guaranteed to do 100 mph. Sadly, there was not enough interest among buyers of the $2195 car, and any thought of production was abandoned. Only the one show car was built.

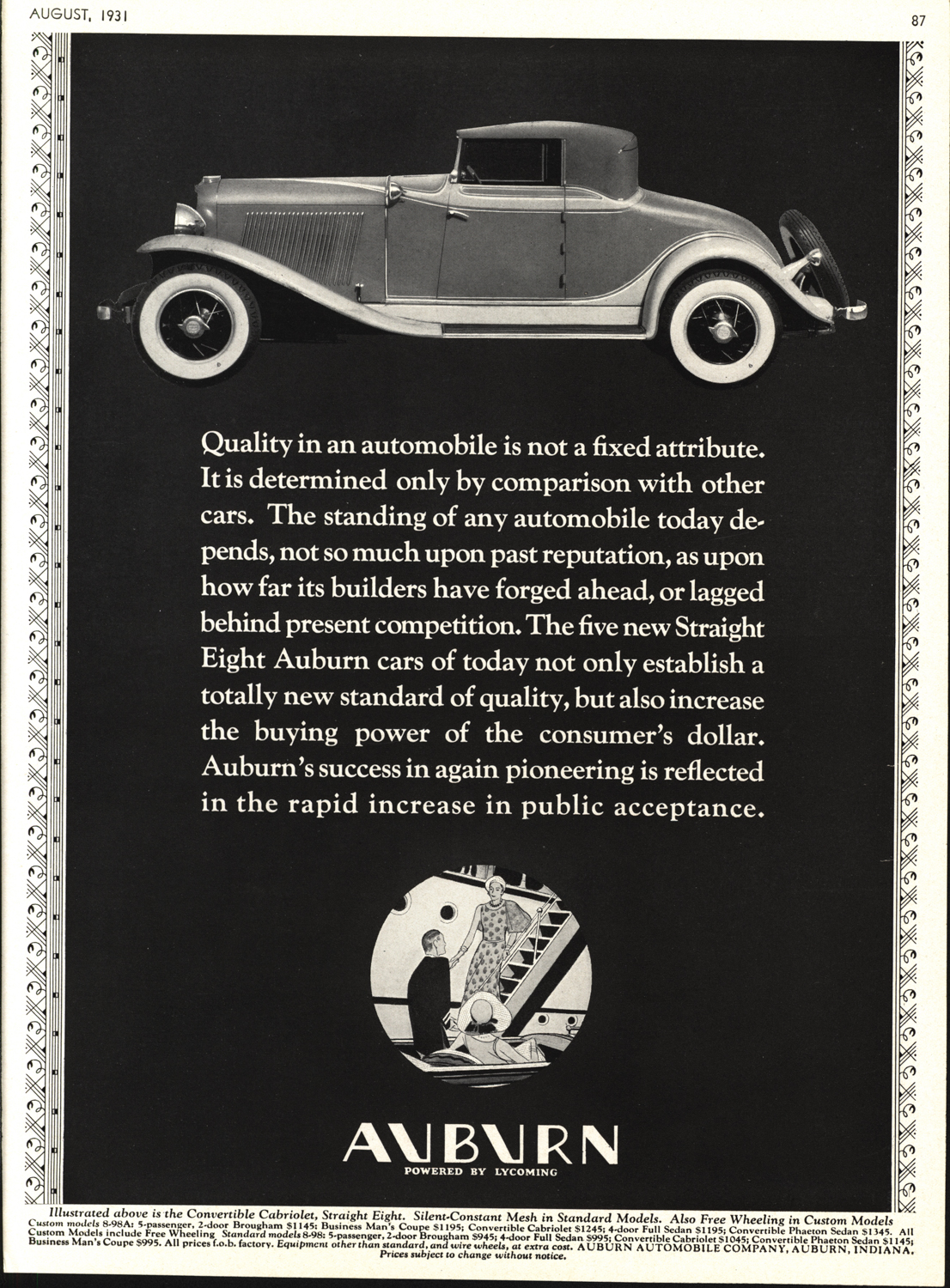

The Depression hurt Auburn, as it did all manufacturers, but E.L. Cord was someone who took action when faced with a challenge. After sales fell to 13,700, Cord reacted and had sales back to 28,103 in 1931. He did it by cancelling several models and concentrating on the new 8-98. The car had a 268.6-cu.in. Lycoming L-Head, 8-cylinder producing 98 hp at 3400 rpm – more powerful than its competition. It had a stronger frame, enhanced by “X” cross-member bracing. The suspension used semi-elliptic springs and Lovejoy double-action hydraulic shocks at each end. There was also an optional L.G.S. Free Wheeling System, controlled by a lever behind the shifter. There were seven models in each of the two lines. The custom models sold for $1195 to $1395, and the cars without the freewheeling system sold for $945 to $1195.

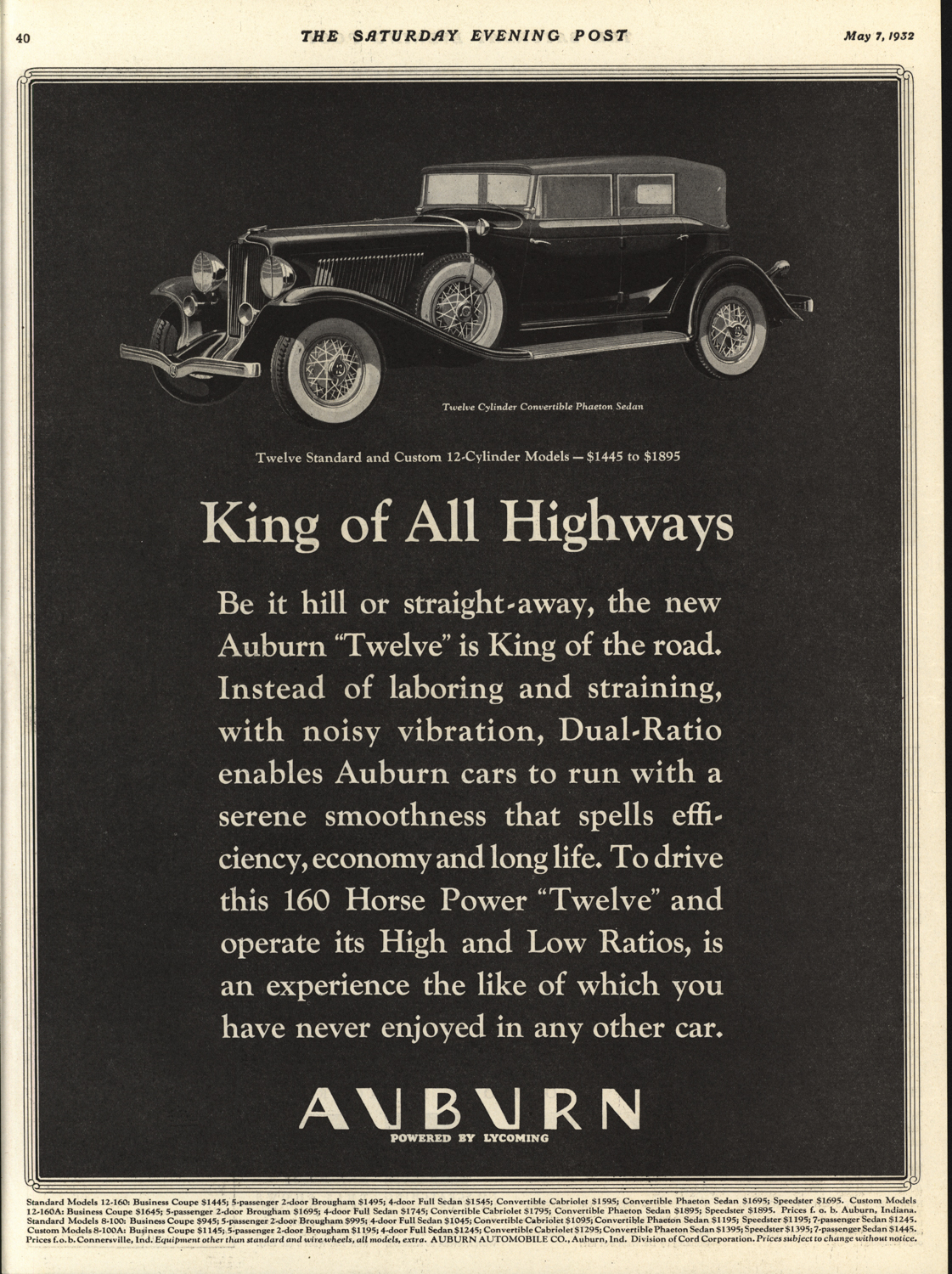

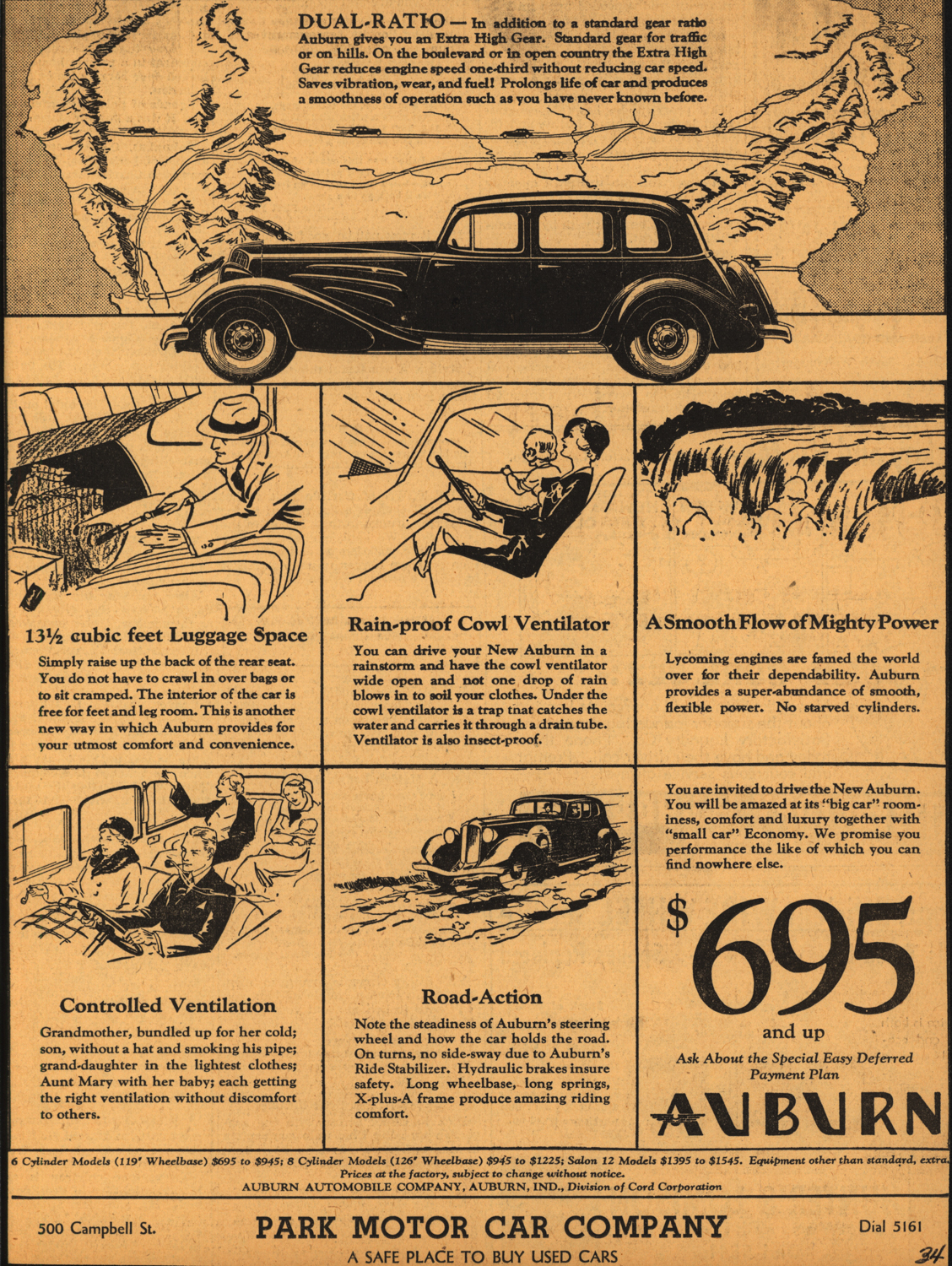

The next move was to introduce a V12 in 1931. It was the least expensive V12 automobile produced in the U.S. The engine was a 45° V12 built by Lycoming to an Auburn design. It produced 160 hp at 3500 rpm. Auburn added a two-speed rear axle called “Dual Ratio.” At speeds below 40 mph, either a 4.55:1 or 3.04:1 ratio could be selected using a knob on the dash. The eight cylinder cars also got the “Dual Ratio,” with either 5.1:1 or 3.4:1 available. Still, 1932 was not looking like a good year for Auburn. In an attempt to direct attention to its new V12, a fully equipped Auburn 12 was run at Muroc Dry Lake in California. The results certainly should have attracted attention:

- Standing mile at 67.03 mph

- Flying mile at 100.77 mph

- One hour at an average speed of 92.2 mph

- 500 miles at an average speed of 88.95 mph

Speed didn’t help. By the end of the year, Auburn had lost nearly $1 million. The next year, 1933, was even worse for the company. Production was down, even though Bob McKenzie drove an Auburn Speedster coast to coast in 57 hours and 38 minutes in an attempt to enthuse the American car buying public.

It got even worse in 1934. The Twelve was too expensive to build and was dropped by the end of the year. A cheaper six-cylinder series was reintroduced. The eight-cylinder series continued but with fewer models.

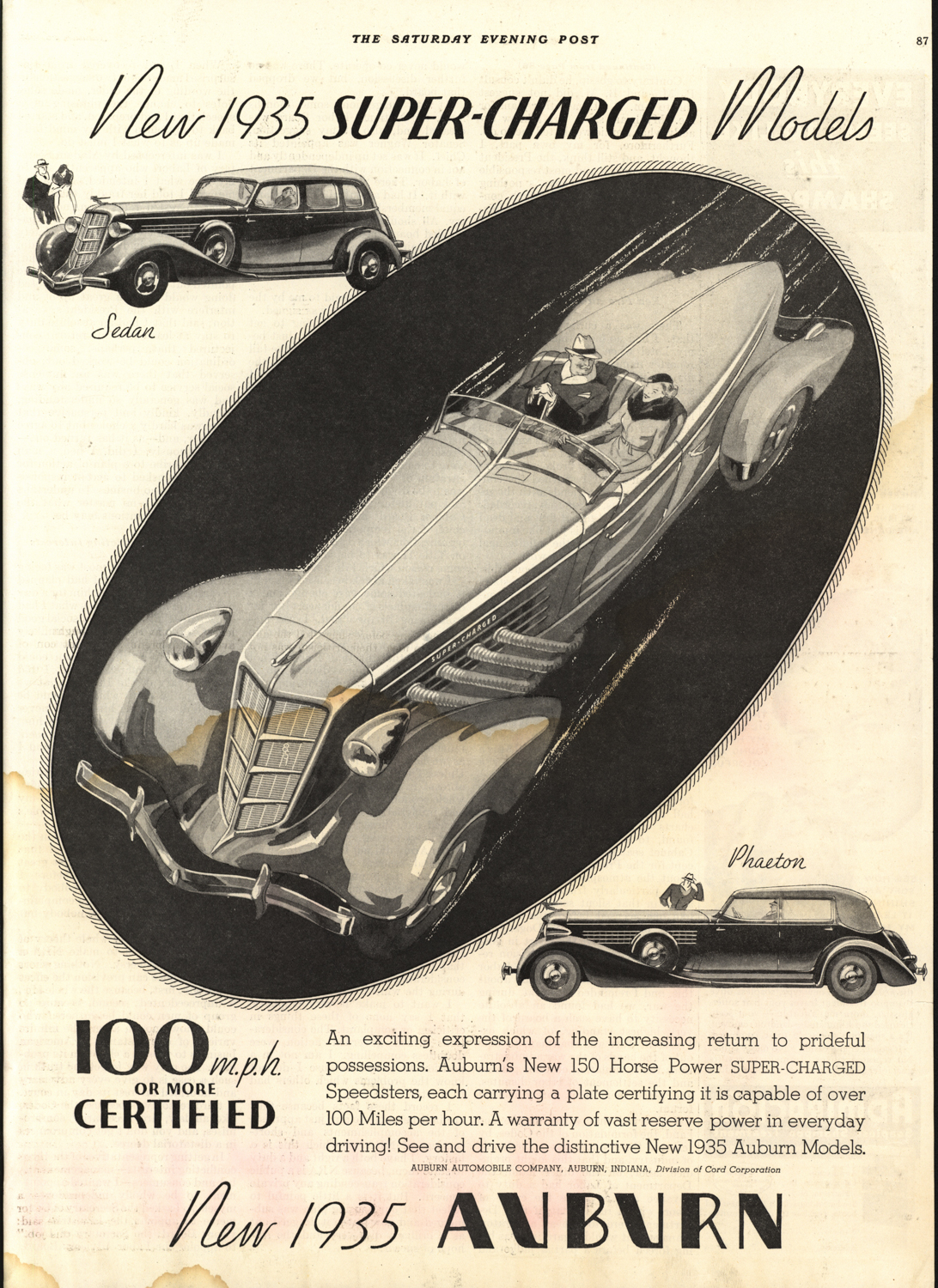

To top it off, E.L. Cord abandoned his company. Cord had expanded his interests into ship building and aviation, and it appears to have become too much for him. He moved his family to England, leaving Auburn to Harold T. Ames, who had been the Duesenberg president. Ames became the Executive Vice-President of Auburn, and he moved from Indianapolis to Auburn, Indiana, with Gordon Buehrig and August Duesenberg. Buehrig was tasked with the design of a new Speedster, and Duesenberg worked on designing a new supercharger for the car. The result was the Auburn 851 Speedster, the mechanicals for which found their way into the other models in the 851 series.

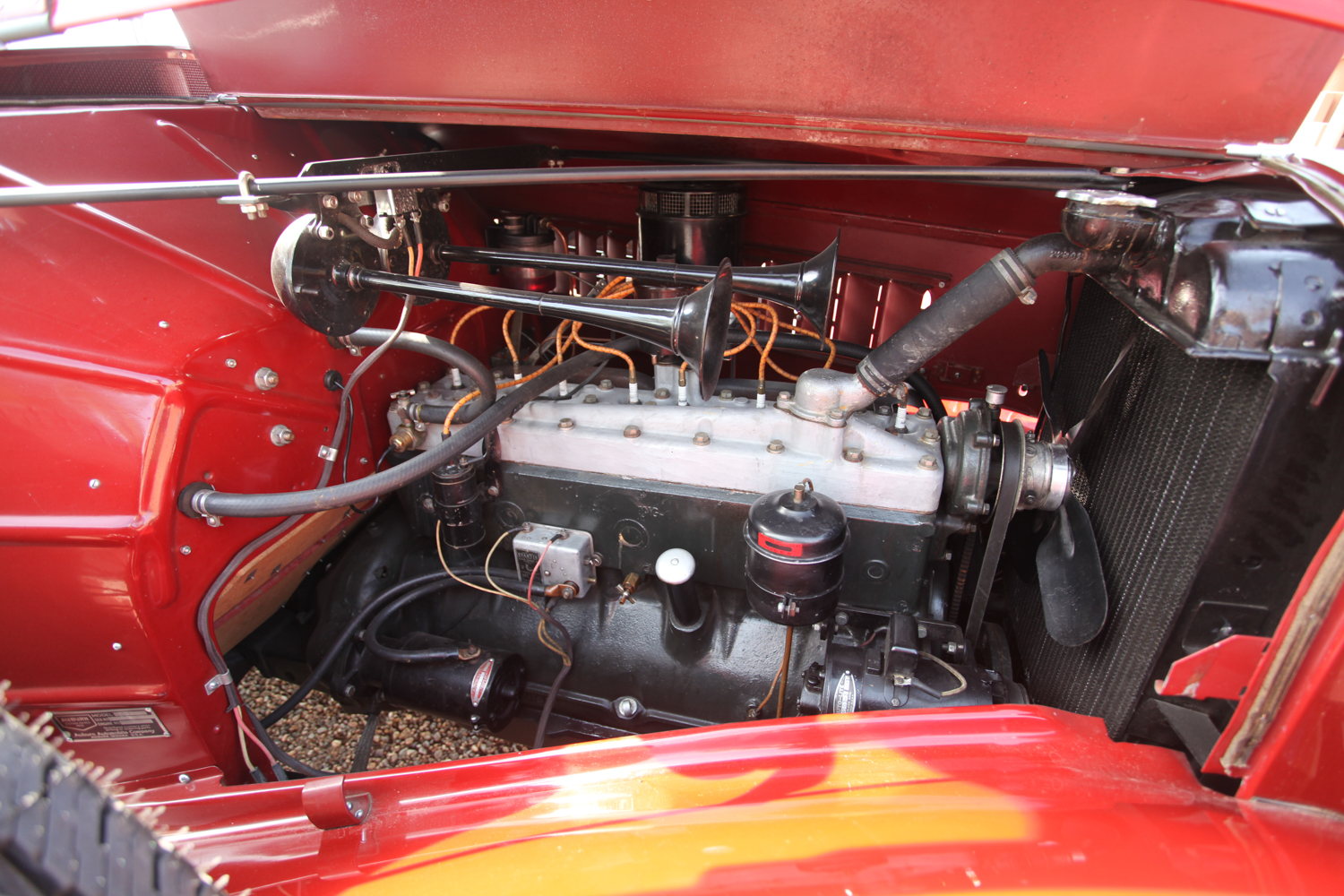

An Auburn 851 used a Lycoming straight eight engine of 279.2-cu.in. and producing 115 hp at 3500 rpm. With the supercharger Duesenberg designed, the engine produced 150 hp at 4000 rpm. Again, there was a dual ratio rear end, selected by turning the knob under the horn button on the steering wheel.

The best thing about the Speedster, for the company, was that it attracted people to the showrooms. Sales were up 20%, but the company was still losing money. When the Cord 810 was announced in 1935, the company focused on it. About the new Auburn 852, Buehrig called it, “our facelift for the year.”

E.L. Cord subsequently returned from England, among rumors that he was being investigated by the IRS and SEC. His return did little for his company. Only 4,830 Auburns were produced in 1937, and they would be the last. In August 1937, Cord sold his holdings to three groups of investors and, by October, Auburns, Cords and Duesenbergs were discontinued. Cord moved west and got involved in ranching, mining, real estate, and politics. He became a millionaire and a recluse.

Auburn 851 Phaeton SN: 2835 H

Officially, it’s a “Phaeton,” but its owner, Eddie Bell, believes it should be called a “Convertible Sedan.” Bell says, “In my book, a phaeton doesn’t have roll-up windows,” and roll-up windows it does have. Bell knew of this car for many years during its restoration. The previous owner, a tool and die maker known for his excellent restorations, had originally bought the car as a parts car for a 1934 sedan, but his wife convinced him to restore it, since it was a convertible. In 2002, Bell received a call from the owner’s wife asking if Bell could drive the car in an event in Colorado. Apparently the owner’s eyesight was failing. Bell drove the car through the mountains and passes – it was perfect, especially with the 2-speed rear end, which produced a 20% difference in rpm between standard and high rear end ratios. Together with its drivability and hydraulic brakes, “it drives as good as anything built in the ’50s.”

When the car became available, Bell bought it. Its performance in the Colorado mountains was not a fluke – it was a very reliable car, and the previous owner’s son drove the car over 400 miles to deliver it to its new owner. ”I think the body style of this car is one of the prettiest of the era,” Bell said. It is built on the same chassis as all from 1934 to 1936, but Gordon Buehrig did some modifications to the ’35 model. Bell feels that those changes, especially the sweeping fenders and the deco details make this a much prettier car than the ’34. “Notice the door hinges. They’re from a Duesenberg, and they’re the same for both the front and rear doors.”

Driving Impressions

This 1935 Auburn is one of the simplest cars to start of its era, or almost any era. Here’s what the owner’s manual says:

“All 851 models are equipped with Startix which starts the engine the instant the ignition lever on steering post switch is moved from “OFF” to “STX” position; therefore do not leave car in gear. Should engine stall, Startix automatically restarts it.”

One item that was left out was probably clear to any Auburn driver in 1935 – the engine starts when the clutch is depressed. Moving the ignition lever to “STX” also turns on the fuel pump.

As pretty as the car is on the outside, it is equally lovely on the inside. When started, the car is wonderfully quiet, allowing my attention to be turned to the controls and gauges. The gauges are plentiful and positioned so they can be easily seen. The dash is simply gorgeous – turned metal plates in front of the driver and passenger – with bezels set in it with all the information a driver or passenger needs. In front of the driver, the bezel on the left includes oil pressure, ammeter, fuel and water temperature. A tach is in the middle with a large speedometer next on the right. Farther to the right and centered in the dash is a round Auburn Crosley radio dial. Inserted in the plate in front of the passenger is a clock.

The transmission is a standard H-pattern three-speed, with reverse above an unsynchronized first gear. Transmission in first, clutch out, we were underway. Bell warned me that the transmission was an older rebuild; the synchros were a bit worn, so I shifted slowly, pausing between gears. Acceleration is smooth, especially for a 3400-pound car. Driving the car was a very pleasant experience. It is comfortable on any road surface, steering is precise, and, with bags of torque, it is easy to accelerate away in second gear rather than shift into the non-synchro first. It handles well, and stopping via the four-wheel hydraulic drum brakes is more than sufficient. This is a very nice road car. Riding behind it while my partner, Dave Allin, got a ride with Bell driving, I was impressed with how quick it accelerated.

Of course, I had to try the “Dual Ratio” axle. At just under 40 mph, I put in the clutch, moved the lever on the steering wheel from “LOW” to “HIGH,” listened for the “clunk,” and let the clutch out. There really was a 20% drop in revs, and we were in high range. To return to “LOW,” you simply put in the clutch and shift down.

This was a pretty amazing car for $1100 in 1935. It is still a pretty amazing and very pretty car. So what happened to Auburn? Kimes, in her article, likened Auburn to a rocket. It moves slowly at first, builds speed until it reaches an incredible velocity, then burns out and falls to earth. The questions that remain unanswered are whether Cord saved or killed Auburn or if the company just offered too much, for too little. No matter the answers, the result is the same – Auburn is gone.