Tom Cantrell’s world revolves around excellence, and it seems he will go to any length to achieve perfection on, and off, the racetrack. The owner of a successful construction business in the Pacific Northwest and a collector of vintage cars, Tom has also built a formidable race team. With a true passion for racing history and a penchant for high horsepower machines, Tom’s stable of racecars is like a who’s who of excellence from the Big Bore era — including the remarkable project seen here.

As a frame of reference for Tom’s project, we first need to set the stage. While small displacement engines dominated racing through the post-war 1950s and early ’60s, the rapidly developing V8 engine quickly became the power plant of choice by the late 1960s. Across Europe and North America, throngs of eager spectators filled the grandstands, infields and surrounding hillsides at every racetrack to witness the spectacle of Big Bore racing.

Grand Touring and Gran Turismo Omologato class sizes swelled, filling with iconic racecars, including Ford’s GT40s, Ferrari’s 250 GTs and Shelby’s Cobras. Seizing on the opportunity to capture a larger share of the car-buying crowd, auto manufacturers Ford, General Motors, Ferrari and others stepped up their game. The horsepower wars were on, reaching an on-track crescendo from 1966 to 1973 in the Canadian-American Challenge Cup, better known as Can-Am.

Unlike many of the previous formulae and series, the Can-Am series adopted essentially a formula libre rulebook. Translated as “free formula,” the only regulations governing a Can-Am car’s specification were the basic configuration and safety. This effectively opened up a blank slate for car builders.

This new, anything goes racing arena attracted a different breed of racer and car builder. A host of smaller enterprises and privateers flocked to the series, fielding cars that broke the conventional norms in every way imaginable. Horsepower was king, resulting in the development of massive wings and slicks to try and tame all that muscle to the track surface. Creativity flourished, and Can-Am cars thrilled crowds everywhere they raced. Today, true Can-Am-era racecars are among the most sought-after vintage racecars on the planet, and only the lucky and courageous few ever attempt to field one.

A Can-Am car was a perfect match for Tom’s racing interests, and through his connections, he was able to locate an authentic period car. A Georgia barn-find turned out to be the one-of-a-kind 1969 Alan Mann Ford Open Sports.

Alan Mann led Ford’s racing operations in Europe, and his enterprise helped develop iconic racecars like the GT40, Daytona Cobra Coupe, Escort and Lotus Cortina. Designed by Len Bailey, the 1969 Open Sports Ford was powered by various engines, including a bored-out, small-block Ford and an aluminum 8.0-liter V8, both using Lucas fuel injection. The Open Sports chassis utilized an aluminum monocoque tub along with many suspension parts from a previous Alan Mann project, known as the F3L (aka the P68).

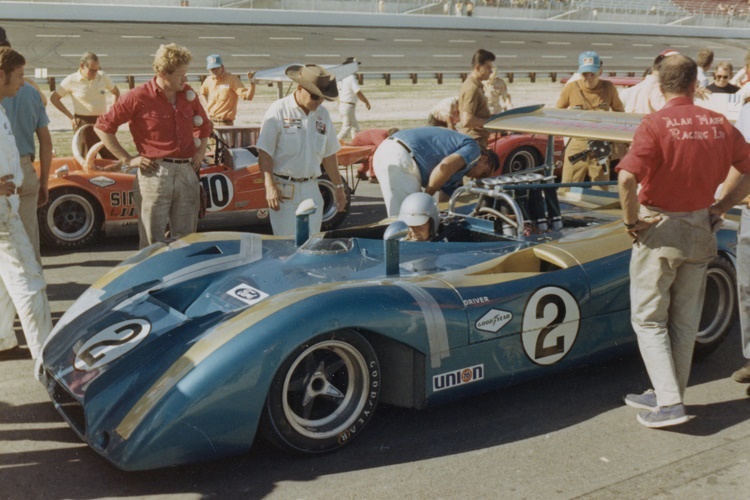

The Holman and Moody-prepared car featured a 494-cid, magnesium, fuel-injected Boss engine producing 740-hp, coupled to a Hewland LG600 five-speed transaxle. Massive 24-inch wide rear wheels helped rocket the metallic blue-and-gold beast down the track, achieving 0-100 mph in just five seconds.

The Ford Open Sport’s best performance was a third-place finish in the Texas International Grand Prix in November 1969, with the legendary Jack Brabham manning the wheel. The car’s other appearance in 1969 was in the preceding round at Riverside where Frank Gardner qualified in 10th but retired with a broken halfshaft. Much has been written about Can-Am in the 46 years since its last race, but many believe the 1969 season may have produced some of the greatest Can-Am cars ever.

As with his other vintage racecars, Tom planned to race the original car in various U.S. historic races. The problem, however, was that this would have required a major updating of the car’s systems, including stripping original parts off the car. This presented a real dilemma for Tom and his team. The car, while certainly sporting a bit of patina from age, was in beautifully well-preserved condition.

The car retained its original paint, Goodyear Blue Streak tires and the aluminum rims it ran on in its final race in 1969. Virtually every detail of the car was exactly as it had been presented on the Can-Am grid that day. How could he justify tearing apart a real piece of history to comply with a sanctioning body’s requirements? For Tom, the answer was easy — you don’t.

Thus started a three-year journey and a true labor of love to restore the car and also build an exact reproduction of the Open Sports Ford. When excellence is the driving force, the word exact means using the same molds, the same tooling and the same style bolts, rivets, and metal alloys found in the original. Every step would follow old-school methods, and the result would be a stunning reincarnation of the original racer.

Tom connected with Bill Rhine at Rhine Enterprise/Rhine Built in Denver, North Carolina. As a leading restorer of historic NASCAR racers, Rhine Enterprise sets a high bar bar for racecar restoration.

It was clear from the beginning that this would be a highly unique project, and once the car was in-house, it rapidly became a collaborative effort. Tom’s team—and Alan Mann Racing in England—assisted the skilled craftsman at Rhine Enterprise to fill in any blanks. Another asset for the build was Kenny Thompson, a talented old-school builder who actually worked on the Holman and Moody cars back in the day, including the Alan Mann Ford Open Sports.

This impressive cadre of talent converged on both the restoration and recreation project, and the team followed a very prescriptive and methodical process. Every inch of the car was mapped out and recorded. A massive amount of photos were taken, and every part and panel were numbered, measured and recorded. When all of that was done, paper templates of every part and panel were made and archived for use in the reproduction process, as well as for any needed repairs in the future.

Tom’s plan was to race the recreation, so in addition to making one new exact part for the new car, a spare part was created in the event of calamity on the track. To say this was a painstaking process would be an understatement, but the results are nothing less than magnificent.

The original Alan Mann Ford Open Sports Can-Am car resides safely in the caring hands of professionals in North Carolina. The new car, with its race-ready fiberglass body, resides in Auburn, Washington, under the care of master mechanic John Anderson. Tom campaigns the car in vintage racing events, including the 2016 Spokane Festival of Speed.

As racing luck would have it that weekend, a massive on-track racing incident occurred during Tom’s race session. Safety crews responded quickly, and everyone at the event stared with dismay at the massive cloud of dust rising into the air at the far end of the track. Minutes seemed like hours, and while everyone held their breath for an on-scene report, out of the cloud and into the pits came a completely dust-covered, blue and gold Can-Am car. Two racecars had experienced serious contact on track, and one of the cars went airborne, flying over Tom and his Ford Open Sports car, narrowly missing his head. Tom was relieved to be in the pits, and a reflective Bill told him, “This is why we race the recreation.”

Vintage sanctioning bodies vary in their view of reproductions like Tom’s Ford Open Sports car. But given the racing landscape and current values of vintage racecars, many vintage racing organizations now welcome accurate and honest recreated racers. They not only serve as a testament to bygone racing eras, but also take a respected place on the grid and a pivotal role in the progression of vintage motorsport.