“First of a New Line”

MG unwittingly gave a glimpse of the future when it created a racing version of the TD for the 1951 Le Mans 24-hour race. George Phillips, an English racer, approached Syd Enever, a designer for MG, to design a streamlined body for his Le Mans racecar, UMG 400. EX 172 was the project title.

The car had an MG TD chassis and engine, but he felt the TD body would suffer aerodynamically on the long Le Sarthe circuit. Alec Hounslow was put in charge of the development of the Le Mans car, possibly because of his experience as Tazio Nuvolari’s riding mechanic when they won the Tourist Trophy, in an MG, in 1933. Enever sketched shapes which Harry Herring turned into ¼ scale wood models. The models were tested in the Armstrong-Whitworth wind tunnel to see how they performed aerodynamically. The final design for the aluminum-bodied car received the approval of company management, so it was off to Le Mans. The body Enever created was only used for that racecar, although the shape would reappear a few years later. One problem with the design was the result of the TD’s narrow ladder frame.

The driver sat on top of the frame, lifting him quite high in the car. Doug Nye, in an article for Automobile Quarterly (“The History of the MGA,” Volume XVII #1, Spring Quarter 1979), described UMG400 this way: “But this car was svelte where the T-series cars were chunky. Its swooping front and rear fenders merged into a curvaceous center section. The cockpit sides were undeniably odd, low-cut with the driver sitting incongruously high, towering above the alleged protection of two vestigial aero screens.” Sadly, Phillips and Alan Rippon, his co-driver, had mechanical problems and dropped out of the race on their 80th lap.

After Le Mans, Enever designed a new chassis that allowed a lower floor and a seat that put the driver in the chassis instead of on it. Herring again did models for wind tunnel testing and, eventually, the result was EX 175 (HMO 6). The chassis was so stiff there was no cowl shake, and the body shape was quite pretty, with the exception of the hood bulge needed for the T-series engine. The prototype was completed late in 1952 and presented to company management as a potential replacement for the TD. The TD had begun showing its age and sales were being affected by its competition. EX 175 was the car MG proposed as that successor. But MG were no longer their own boss, since they had become part of the British Motor Corporation in 1952. The proposal to work on a new model was overruled by BMC management; they wanted to concentrate on the Austin-Healey 100, which they feared would have to compete with the new MG. Instead, a decision was made to facelift the TD while the new MG was developed in the background.

The result was the MG TF, which was launched at the Earls Court Motor Show, in London, in October 1953. It was not well received. One unnamed journalist called it “a TD with the front pushed in.” Ultimately, it became quite a sales success, with 9600 TFs being sold during the 19 months it was in production. Still, it was a stop gap model.

Len Lord at BMC was no fan of the products that came from the Nuffield side of the company. This might be due, at least partly, to an encounter in 1936. William Morris had asked Lord to run the Nuffield businesses but refused to give Lord a share in the business. As a result, Lord went to Austin. In 1952, Lord was running the new BMC, which contained MG. Countering Lord was John Thornley, General Manager of MG. Thornley was an MG enthusiast, even becoming the Honorary Secretary of the MG Car Club and writing a book on MG racing. Eventually, the need for a modern replacement for the T-series cars was acknowledged. MG was allowed to create a design office and a competition department, along with what would become the MGA. Along with the approval, though, came a very tight schedule; BMC wanted the car by April 1955 – less than a year away! Enever, who had become the Chief Engineer at MG, said, “We have been sitting on the thing for two years, and suddenly it was all panic and scurry. Huh! Management.”

The project was designated EX 182. The development team for the MGA at Abingdon included engineers and designers from other BMC plants. Importantly, the managers at those other plants agreed not to interfere. The team threw themselves into getting the car done on schedule. One team member, Jim O’Neill, put off a hernia operation until the bulk of the design was completed. Much was already done – the suspension would be modified TF, and the body would be based on HMO 6 – so a lot of the work was changes in details. The body changes, for example, included a smooth hood, bigger trunk lid, and slimmer front fenders. The design was completed in nine months.

Separately, a family of overhead valve engines was being designed to replace 11 older engines, including the Nuffield engines in the T-series cars. An “A-series” engine would be used for small cars like the Mini, the “B-series” engine was for medium class cars like the MGA, up to the “D-series” engines for bigger vehicles. Harry Weslake had done his magic on Austin cylinder heads in 1947, and that design would be used on these engines. The B-series engine was designed by Erid Bareham so that it could have displacements from 1200-cc to nearly 1500-cc. Ultimately, the engine would be used in the MGB and have a displacement of 1800-cc. Bareham called the engine “theoretically horrible.” Pushrods and ports were on the same side of the engine – very crowded. Cylinders 1 and 2 used the same intake port, and cylinders 3 and 4 used one other intake port. Cylinders 1 and 4 had their own exhaust ports, while cylinders 2 and 3 used a common exhaust port. There ought to have been induction problems, but the engine worked very well. MGA engines would have a compression ratio of 8.3:1 and would produce 72 bhp.

There had been a decision, based on the number of TFs sold, not to use a monocoque design for the body and chassis. The reasoning was that another small run of a new model did not justify the cost of the tooling for a unibody design, and they believed no future MGs would use unibody construction. They did not anticipate the success of the MGA, of which over 100,000 were sold, nor did they anticipate that the design of the next model, the MGB, would assume that a unibody approach would be used. With the design done and B-series engines available, the car was ready for production. Except the tooling for the body panels was not ready. The Pressed Steel Company, who were to produce the body panels, wanted to try new plastic tooling as a cost saving. They offered to develop the tooling for free and, in case it did not work, to build the conventional tooling at an agreed price. The plastic tooling did not work, so body panels for production were delayed for months.

MG, for the first time since 1935, had a competition department, so it was decided to enter the new cars at Le Mans in June 1955, shortly after production had begun. The intent was to qualify for the Biennial Cup in 1956. They had to be entered for the first time in 1955, average over 80 mph during the race, and had to win their class in 1956 to take the Cup. The race cars had removable aluminum panels, reducing the car’s weight from 1904 pounds to 1596 pounds. Weslake reworked the cylinder head, cams were profiled, and compression was raised to 9.4:1, resulting in 82.5 bhp at 6000 rpm, versus the stock 68 bhp. Twelve race engines were built, none using head gaskets. Instead, the head and block were hand lapped for a perfect fit. Because there were not yet any production versions of the MGA, the cars would be entered in the prototype class. Four cars were built (registration numbers LBL 301 – LBL 305) and were as follows:

- Number 41, engine number 182/42, chassis number 182/38 would be driven by Ken Miles and Johnny Lockett

- Number 42, engine number 182/43, chassis number 182/39 would be driven by Dick Jacobs and Joe Flynn

- Number 64, engine number 182/44, chassis number 182/40 would be driven by Ted Lund and Hans Waeffler

- Number 40, engine number 182/45, chassis number 182/41 was the spare car.

The cars were driven from England to the race! But 1955 is sadly remembered for Pierre Levegh’s horrible crash. Jacobs, in #42, was distracted by the accident and hit a bank. The car was totaled and Jacobs seriously injured. The other cars did well, with #41 finishing 12th overall and 5th in class at an average speed of 86.17 mph; #64 finished 17th overall and 6th in class. Only 19 cars were qualified as finishers. Sixty cars had started the race. After the race, one of the racecars and an MGA prototype took a 2000-mile tour of Europe, ran on several tracks, and did numerous road tests. “Autosport” reported: “At long last the public is willing to forget the sports-lorries of 1929 and this MG has just the sort of look that they will be after.” There were no MGs at Le Mans in 1956 to try to win the Biennial Cup, even though they had the opportunity thanks to the two cars that finished in 1955.

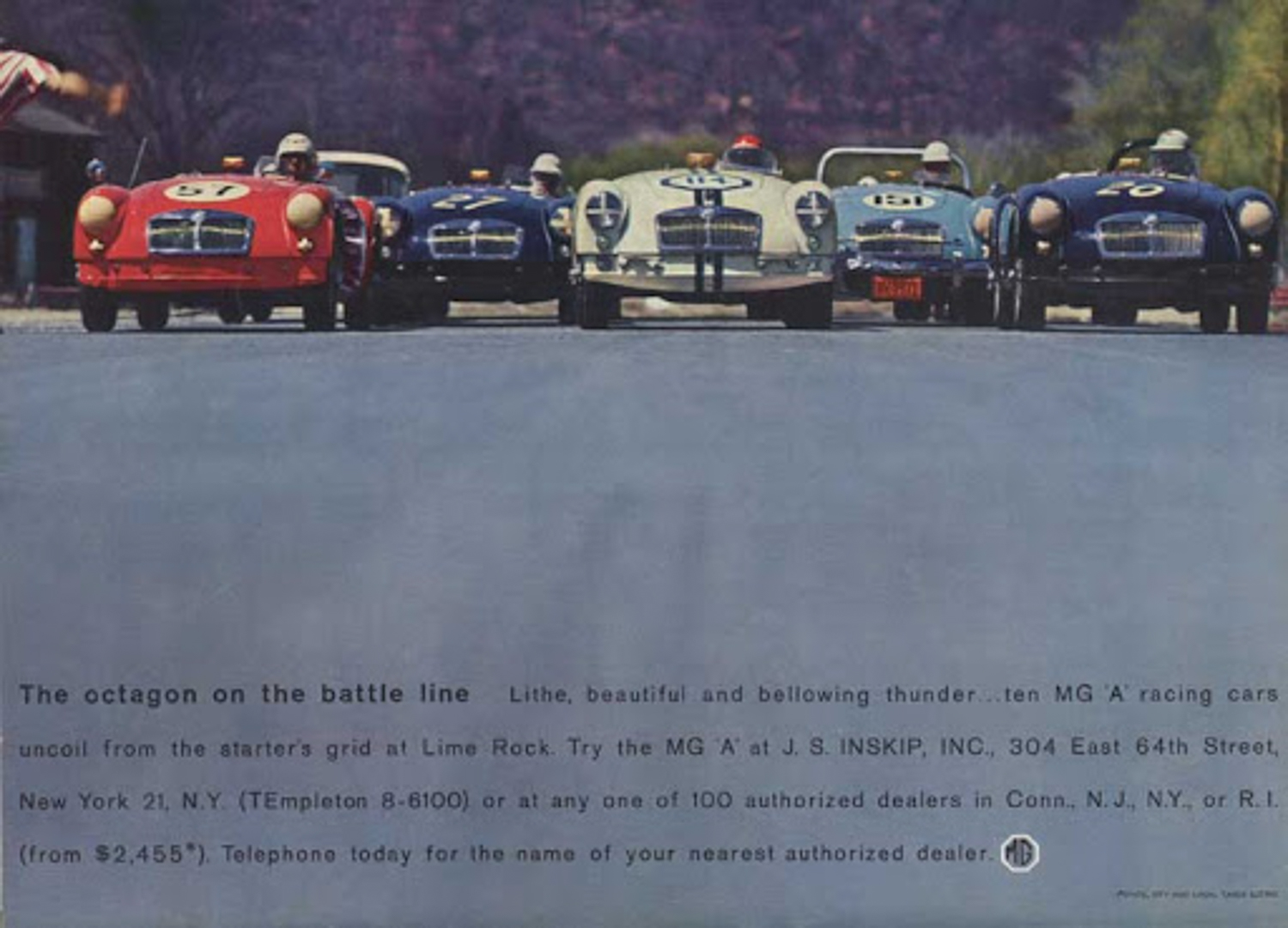

The official launch of the MGA came at the Frankfurt Motor Show in September 1955. Unlike the racecars, the show cars were flown to Germany. It was an instant hit. John Bolster, writing for “Autosport” said: “This is a jolly good little sports car; if you want one, hurry up and get in the queue.” The first MGA built was a right-hand-drive car in Tyrolite Green with a grey interior. At the same time, a left-hand-drive prototype was being built. It was Orient Red with black trim. There were 1063 MGAs built by the end of 1955; all but 90 of them were for export. The next spring, the MGA was shown at the New York Auto Show and resulted in 3600 orders for the new roadster. Jocelyn Hambro intended to market British products in the US. His Hambro Automotive Corporation became the U.S. broker for MG, and the MGA made him very successful. North America counted for more than 80% of MGA production.

The MG plant at Abingdon was small, so major components were often built in other facilities then attached to the chassis at Abingdon. It must have been a hectic time for MG and its workers. There were problems on the productions line. According to John Price Williams, examples of the issues included a few right-hand-drive cars with the pedals on the left and some cars with wire wheels on one end and steel wheels on the other. MG had inspectors who worked hard to insure any problems were corrected. Every export car was driven six miles by an inspector before it was covered with protective wax and taken to a staging center for shipping.

Clever marketers at MG suggested early on that a coupé would keep interest up for the model. It was designed by Eric Carter who worked at Morris Motors. In March 1956, he used a black roadster as the basis for his design. There were few actual changes to the MGA roadster body, except where the roof joined the body. The new fixed roof design was taken from the roadster’s removable hard top. It was single pressed and welded to modified roadster bodies at Bodies Branch in Coventry. The car Carter designed had a nice rear window, wind-up windows, sound deadening, carpet between the seats, door locks, and unusual vertical door handles.

It was the first MG coupé since the 1930s. October 1956 saw the first coupés come off the production line, but only 16 were built by the end of the year. At £699, it was £59 more than the roadster and 98 pounds heavier. But better aerodynamics made the coupé a true 100 mph car. MG promotions for the coupé said: “It gives him the motoring he loves and her the comfort she demands.” There were some comfort issues, though. It was not an easy car to enter or exit, and engine heat was a problem in the footwells – possibly one of the reasons the car was not very popular in the U.S., where temperatures are often higher than in the UK during the summer. The coupé was also noisy, in part because the spare tire stuck partly into the passenger compartment. MG moved the spare fully into the trunk in 1959, which made the car quieter and provided more room behind the seats but took away much of the luggage space in the trunk. The coupé was part of all the MGA variations, but it accounted for less than 10% of total sales.

The next significant change to the MGA was the Twin Cam in 1958. It was intended to compete with Porsches in sports car racing in the U.S. with up to 100 cars produced. MG proposed to build 50 per week, but BMC dictated that 75 be built each week. There were some significant problems with the engine – pistons burning, especially when low octane gasoline was used; high oil consumption; and a high level of engine noise. The Twin Cam got a reputation for poor reliability, although some of that reputation was probably caused by allowing the wrong people to own the cars. The factory worked hard to resolve the problems with the engine and made considerable progress, but it was too late, and the Twin Cam was killed in 1960 after 2111 had been built. Unused Twin Cam parts, such as disc brakes and wheels, were offered as optional equipment for the MGA 1600 MKII.

With the exception of the coupé, nearly all the significant changes to the MGA were in the engine. This chart shows the changes and when they were made:

| MODEL | PRODUCTION | ENGINE TYPE | BORE/STROKE | DISPLACEMENT | POWER |

| MGA 1500 | 5/55-1/59 | 15GB | 73.025/88.9mm | 1498cc | 68/72bhp@5500rpm |

| 1/59-5/59 | 15GD | 73.025/88.9mm | 1498cc | 72 bhp@5500rpm | |

| MGA TWINCAM | 4/58-5/60 | 16GB | 75.39/88.9mm | 1588cc | 108bhp@6700rpm |

| MGA 1600 | 5/59-3/61 | 16GA | 75.39/88.9mm | 1588cc | 79.7bhp@5600rpm |

| MGA 1600 MKII | 3/61-5/62 | 16GC | 76.2/88.9mm | 1622cc | 86bhp@5500rpm |

The 1500 engine was used in about 60,000 of the MGAs. In 1959, it was felt that some changes were needed. There were small styling changes, but the engine was the big change. The new overhead valve engine was built on the Twin Cam block, a 1588-cc engine. The increase in engine size to the 1600 provided 10% more power and 12% more torque. As expected, it was faster than the 1500. In 1961, displacement was increased again to 1622-cc for the final version of the MGA, the 1600 MKII. The compression ratio was increased from 8.3:1 to 8.9:1, the cylinder head was improved, and the flywheel was lightened. The most noticeable changes to the outside of the car were that MKII was added to the 1600 badge and the slats in the grille were now vertical. There were now options not available before. For £26, a new owner could have a heater, windshield washers, adjustable steering column, and headlight flashers. The best option, though, was four-wheel disc brakes.

The MGA was intended to last only three years, but problems with the development of the MGB caused it to stay around much longer. Seven years of MGA production made a significant number of cars available for people who wanted to use them in competition. While MGAs did not return to Le Mans in 1956, there were many successes in both racing and rallying. MGAs competed at Sebring, in the Mille Miglia, the Monte Carlo Rally, and the Tulip Rally, to name just a few events. In the U.S., MGAs were popular in Sports Car of America (SCCA) races, although it was not until 1986 that an MGA was driven to an SCCA national championship. In fact, Kent Prather drove his beautiful MGA roadster to six SCCA championships in G Production between 1986 and 2005.

Two That Were Saved

MGs are favorite cars among the members of the Southern British Car Club, and several of those are MGAs. Two were chosen for this profile, an early (1957) 1500 coupé and a late (1962) 1600 MKII roadster. Both were saved from the scrap yard and restored by their owners. Both are regularly driven, sometimes for long distances. They are often seen at British car events and on road tours. A lot of energy and love went into the restorations of these two cars.

1957 MGA Coupé HMR4338593

Dave Terhune says, “there is literally nothing special about my coupé,” but he is wrong. It is beautiful, and the trophies he’s won prove him wrong. In a handout he prepared about his car, he began with a quote from a 1956 advertisement for the coupé: “A greater measure of comfort and elegance for the enthusiast wishing to move into something more civilized.” Nice praise for the new coupé, but not very kind to the early roadsters. New, the coupé cost $2750 in 1956, that’s over $26,000 in 2021 dollars. Terhune found and bought the car in 2003. It had sat abandoned since 1990 outside a home in Houston, Texas. It was weathered, possibly flood damaged, and a candidate for the crusher. Terhune says: “I believe the car was raced at one time, as there were old roll bar mounts on the frame and a patched hole in the windshield scuttle that looks like a vent commonly found back then.” He also found indications that the car did not have its original frame, “I don’t believe the frame belongs to this car. I believe the frame is from a 1600 car based on the brake line mounting tabs.” It was advertised as a 1959, but Terhune was able to verify from the VIN that it was a 1957.

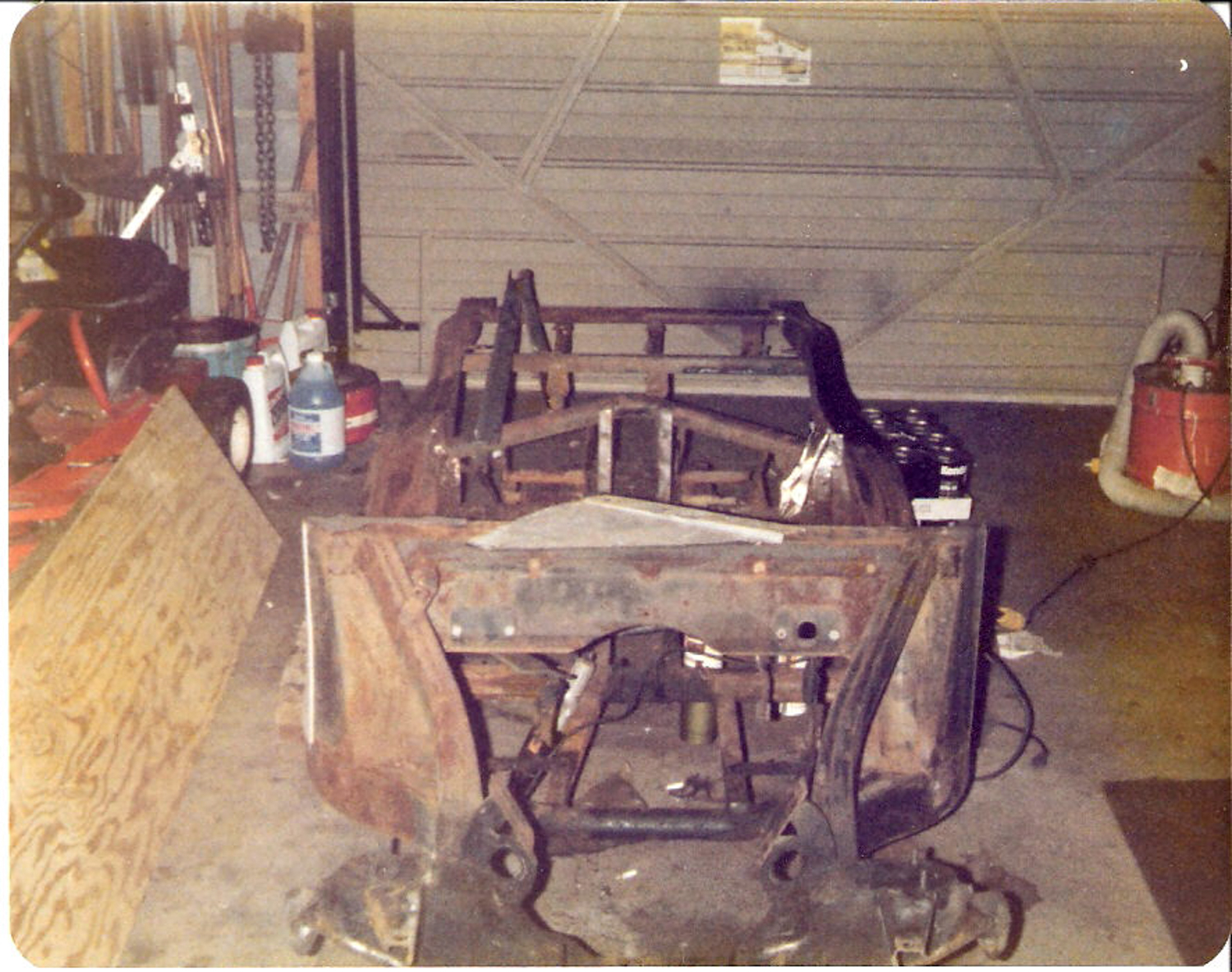

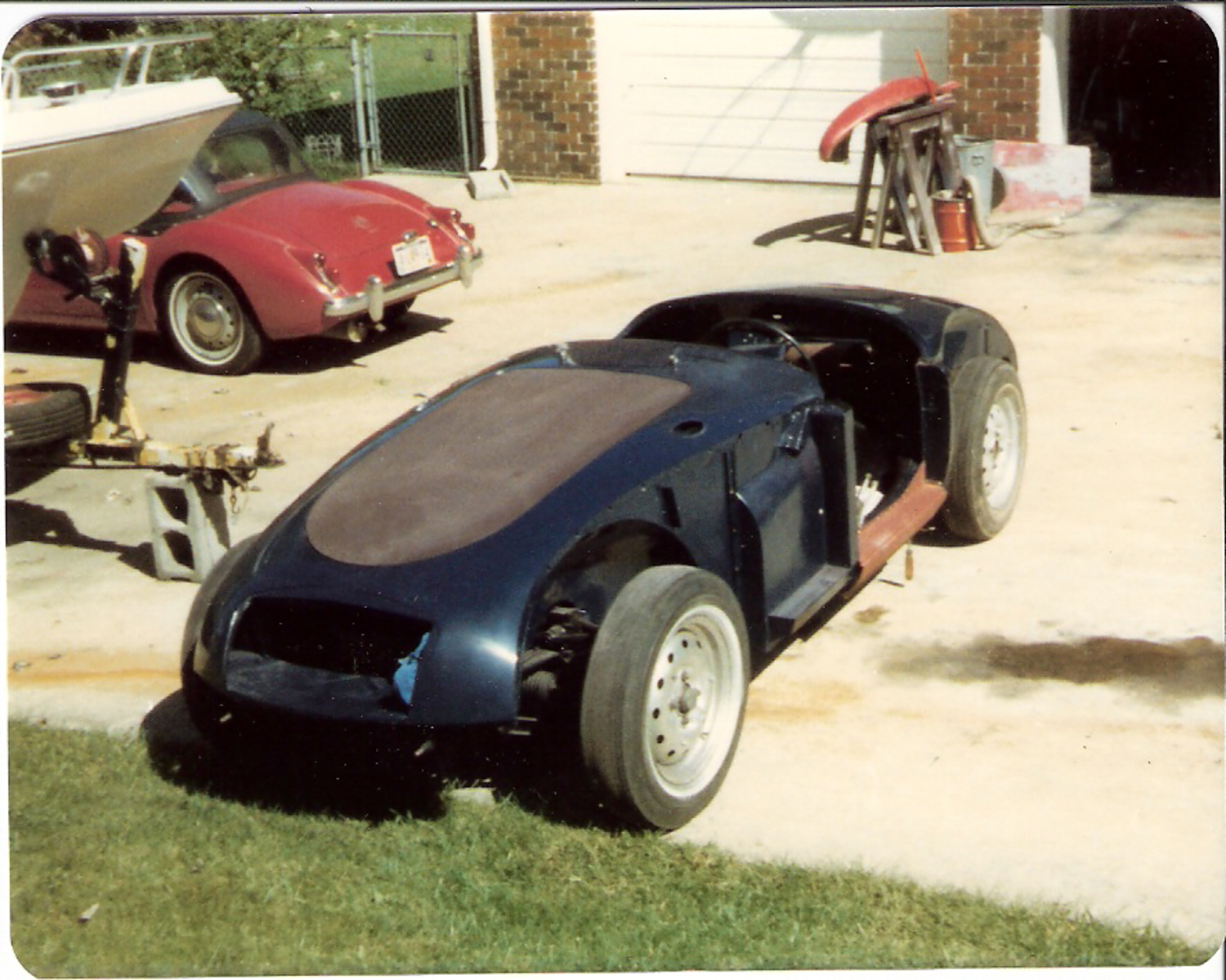

Terhune saw the potential and undertook a five year restoration. There were surprises. The rust was more than he expected, and the mud in the headlight buckets suggested that the car had certainly been under water at some time, maybe during one of Houston’s hurricanes. After removing the body from the frame, Terhune convinced a local grape farmer to keep it in his barn . . . for two years.

With a borrowed sand blaster, he cleaned the frame. It was a long process, since the compressor needed recharge time, and he needed to recycle the sand several times. Accident damage he found was corrected by Eclectic Motors in Holland, Michigan, not far from where Terhune had moved. Thankfully, Eclectic Motors determined that the frame was straight, so reassembly began using a number of new panels. The only original panel that remained was the driver’s side rear fender. Terhune’s wife, Teresa, picked Dove Grey for the color of the car, and it was applied by a high end hot rod shop.

Terhune has updated the car to include a replacement engine; insulated the floors and doors; installed disc brakes, sway bar, and MGB rear end for a more desirable drive gear, and added LED lights. His coupé is a very nice driver’s car and has even turned a few laps at Road Atlanta.

1962 MGA 1600 MKII Roadster GHNL/2 108923

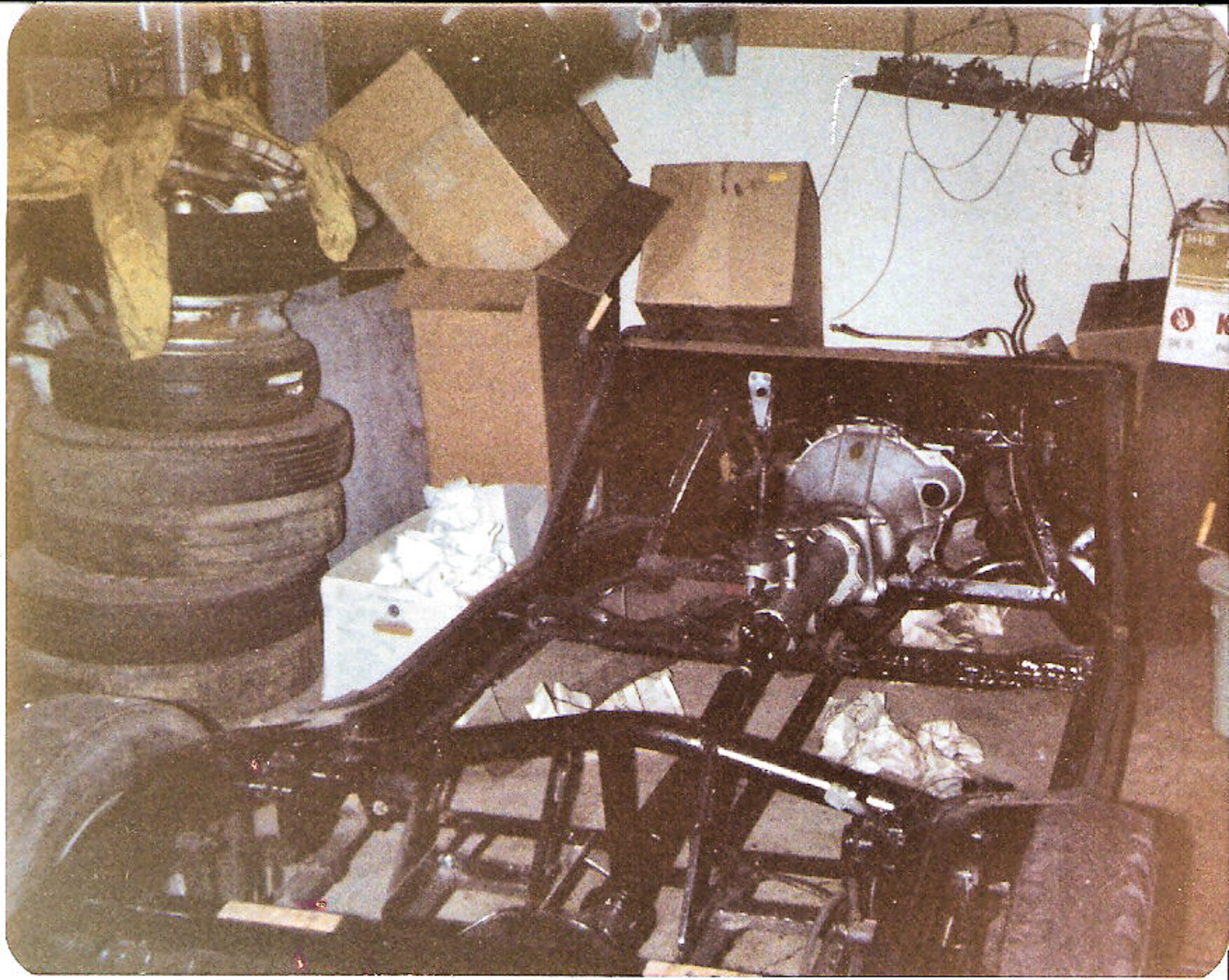

Gil DuPre may not have had quite the number of surprises with the roadster he purchased in 1975. It really was a 1962, and it was all original. Still there was plenty to do to make the car presentable again. The previous owner had wrecked the car by running it up a guidewire for a power pole and rolling it over. Most people would have looked at this poor roadster and moved on, but DuPre saw the car’s potential and started the restoration. The engine was rebuilt in 1975, but that was the easy part. It then took until 1983 for DuPre to finish the restoration.

Both DuPre and Terhune should be thanked for rescuing these classic British cars, as well as for using them as they were intended.

Covid-19 makes it unadvisable to do driving impressions with two unrelated people in the car, especially in a car as small as the MGA. An alternative is to find period road tests, and Google is great for that kind of search. Terhune, though, had a copy of a road test done by The Motor on August 7, 1957. The writer was impressed with the car’s lack of body shake because of the “high stiffness of the chassis and body. This high stiffness factor . . . gives the driver and passenger a psychological impression that high speeds can be maintained in safety . . . whereas some more flimsily built vehicles . . . impose strain and anxiety upon the occupants.” Handling was very good, approaching racecar cornering. Brakes were good. Rack and pinion steering was positive. The clutch was firm on the take-up and allowed quick shifts. One complaint was that the pushrod engine was far from quiet, but it was probably easier to hear the engine because of the lack of wind noise. While the coupé is heavier than the roadster, it was faster (100 mph) and more economical (over 30 mpg). He admired the seats, saying they gave good support. The suspension was stiff, helping the handling, but “long high-speed journies cause little physical and no mental fatigue.” He liked it.

A Google search led to a Motor Trend review of the 1600 MKII from October 1961. It is apparent that the magazine has a favorable opinion of the MGA and MGs in general: “. . . MG is automatically recognized as a sports car by the U.S. motoring public. No one need make any excuses or qualify the term in any way – MG fits. . . . In its price category it has come to be the standard against which other sports cars or would-be sports cars are judged.” After noting the few facelifts, the article praises the B-series engine as very reliable and the improvement in performance of the 1622 cc engine, including its ability to remain cool in all kinds of driving – from spirited to stop-and-go traffic. They also liked the car’s stopping power, moderate brake pedal pressure, and resistance to fading.

Their highest praise was for the car’s predictable handling. Steering is quick while giving the driver plenty of feedback. There was minimal body roll, and the ride was firm, which is seen as a good thing in a sports car. The car has a “desirable tendency to understeer, again telegraphing its intentions to the driver – . . . nothing tricky or difficult as in the case of some extremely high-performance sports cars.” These characteristics “make the A a good learner’s car [and] a delightful general purpose street machine.” Power and torque were judged to be more than acceptable, and the seats were comfortable. There were a couple of criticisms, though. A lack of cockpit storage, the small trunk, heat from the transmission tunnel, and wind noise with the top up and the side curtains out. As a summary statement, they said, “But as a fun car, an automobile that features basic driving pleasure, it is hard to beat. The limitations of a two-seat roadster are quite obvious. If these can be overlooked, the MG-A 1600 MI II is an outstanding automobile for the money.”

During its seven years in production, the MGA was the most successful MG until that time. A total of 101,081 MGAs were built, of which 58,750 were 1500s, 2111 were Twin Cams, 31,501 were 1600s, and 8719 were 1600 MKIIs. Terhune’s 1500 coupé was one of 3326 left-hand-drive coupés exported to North America in 1957. DuPre’s 1962 MKII was one of 165 roadsters exported to North America that year. The MGA set records and was a great success for MG. Then came the MGB.

SPECIFICATIONS

MGA 1500 Coupé

Body Type Two-seat convertible

Engine Overhead valve in-line four cylinder

Displacement 1498 cc/90.9 ci

Bore/stroke 73.025 mm (2.9 inches)/ 88.9 mm (3.5 inches)

Compression Ratio 8.3:1

Carburation Twin semi-downdraft SU.

Power output 72bhp @ 5500rpm

Maximum torque 77lb ft @ 3500rpm.

Clutch & Gearbox Dry clutch, part synchromesh 4 speed manual.

Brakes Lockheed hydraulic, 10″ drums all round.

Tires 5.60-15″

Wheels 4Jx15 steel disc or center lock wire wheels.

Front Suspension Front; coil springs, wishbones and lever arm dampers

Rear Suspension Live rear axle, half elliptic leaf springs and lever arm dampers.

Wheelbase 94.0 inches/2388 mm

Front Track 47.9 inches/1217 mm

Rear Track 48.7 inches/1237 mm

Length 156 inches/3962 mm

Width 58.0 inches/1473 mm

Height 50.0 inches/1270 mm

Weight 2000 lbs/907.185 Kg

MGA 1600 MKII

Body Type Two-seat convertible

Engine Overhead valve in-line four cylinder

Displacement 1622 cc/98.981 ci

Bore/stroke 76.2 mm (3 inches)/88.9mm (3.5 inches)

Compression Ratio 8.9:1

Carburation Twin semi-downdraft SU.

Power output 93bhp@5500rpm

Maximum torque 97 lb ft @ 4000 rpm

Clutch & Gearbox Dry clutch, part synchromesh 4 speed manual.

Brakes Lockheed hydraulic, 10″ drums all round.

Tires 5.60-15″

Wheels 4Jx15 steel disc or center lock wire wheels.

Front Suspension Coil springs, wishbones and lever arm dampers

Rear Suspension Live rear axle, half elliptic leaf springs and lever arm dampers.

Wheelbase 94 inches/2388 mm

Front Track 48.7 inches/1238 mm

Rear Track 48.7 inches/1238 mm

Length 156 inches/3962 mm

Width 58.0 inches/1473 mm

Height 50.0 inches/1270 mm

Weight 2044 lbs/927 Kg