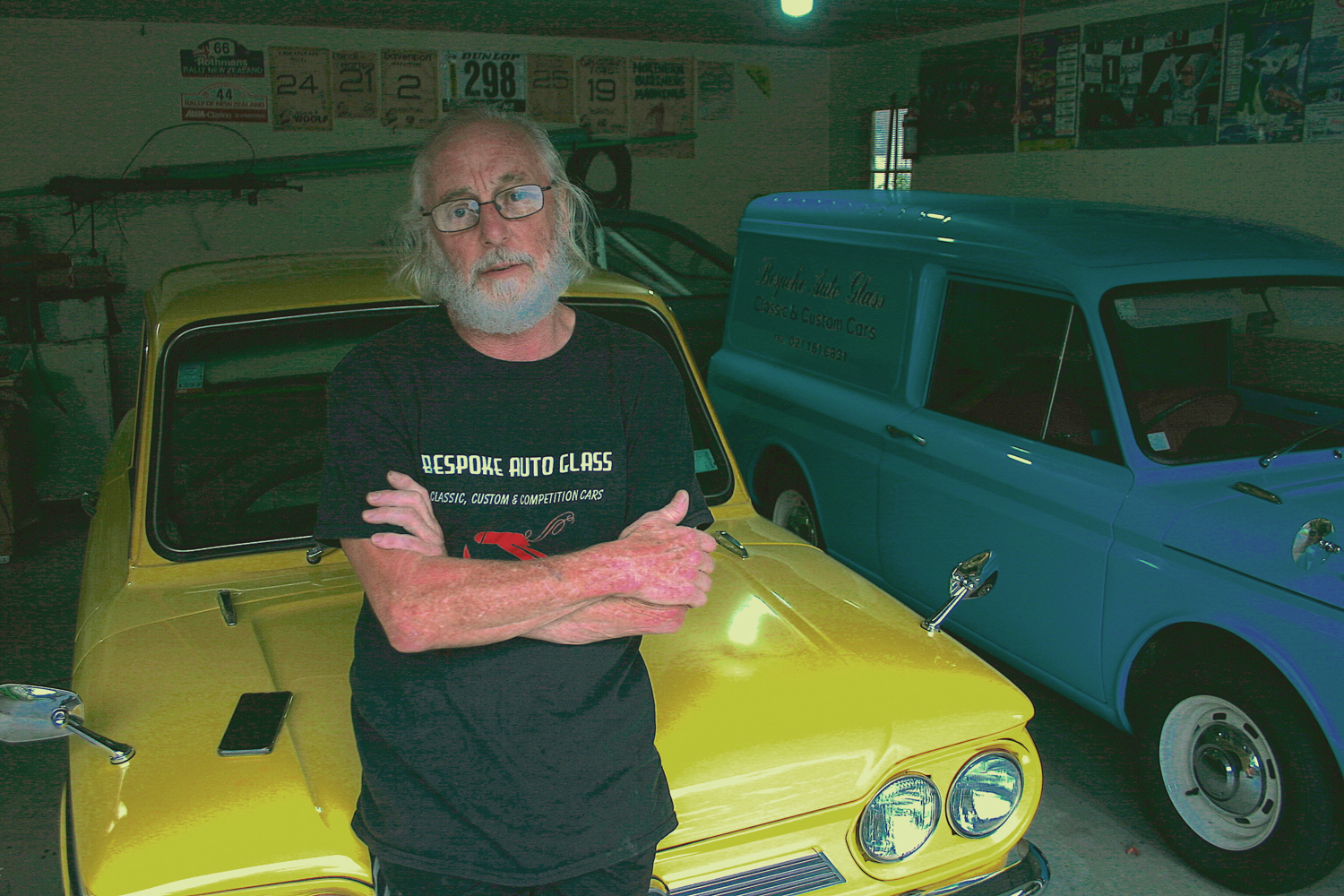

The car looked pleasant, though unexceptional at first glance, but as it turned out, it was quite unique, and had an interesting story behind it. Its owner, a fellow named Jeremy Tagg— who installs glass in vintage and classic cars professionally — took the time to fill me in on the intriguing design aspects of this pint-size people perambulator that also makes it a potentially piquant rally car instead of the no frills transportation it was designed to be, but more on that later.

I arranged an opportunity to drive the little sedan, as well as Tagg’s very rare restored van version of it called a Commer, at his house north of Auckland that next weekend. When we turned onto Jeremy’s street we spotted his place immediately, because the two cars stood out from half a block away in their bright canary yellow and robin’s egg blue paint jobs.

Jeremy goes over the unique features of the Imp with me one more time, and then hands me the keys. I climb in, and to my surprise, the little car is quite roomy, with plenty of leg and headroom, and wide enough to be quite comfortable for two six-footers up front. Oddly, there is a small cold-weather priming lever on the floor next to the shift lever. The four-speed all synchromesh transmission has the usual H-gate arrangement, but with reverse all the way to the left and down.

I bend down and flick the priming lever, and then twist the ignition key of the 875-cc rear-mounted, aluminum, single overhead cam four-banger, and it coughs to life. The exhaust note is more like that of a motorcycle than any car I am familiar with. All of the controls are cable actuated because the engine is in the rear, so the accelerator pedal doesn’t do much until it is depressed about half way down. This causes me to stall the car a couple of times before getting the hang of it, because the engine needs to rev to make much torque.

The clutch doesn’t start to disengage until the pedal is almost to the floor, and the shifter is very VW Beetle-like. The feel is that of a broomstick in a bucket of ice until you get used to it. The big difference between the Imp and the VW is the Imp’s engine loves to rev, and is at ease up to as high as 6,000 rpm. In fact, racers build them to turn 10,000 rpm without instant entropy.

Braking is good, and the turning circle is surprisingly tight. Acceleration is sprightly thanks to the fact that the car only weighs 1,598 pounds including its engine and transaxle combination, which together weighs a mere 175 pounds! I need to give the Imp a little throttle to get the rpms up, but once I do, it sprints away quite nicely, and even in stock form will do 90, while a contemporary Volkswagen is all done at 72 miles per hour.

So why do we not see many Imps at British car meets these days? Our 1969 test car is roomy, economical, decent looking, practical, lightweight and fun to drive. It can do anything a contemporary VW Beetle or Mini can do, and it debuted replete with a number of cutting edge innovations in 1963. But sadly, the Imp never came close to the success of the Mini or the Beetle, and is indeed often cited as hastening the downfall of the Rootes Group, which was bought out by Chrysler Europe in 1967.

In fact, its less than sterling reputation earned the Hillman / Sunbeam Imp an ignominious inclusion in Giles Chapman’s book “The worst Cars Ever Sold”, as well as a mention in Tony Davis’ “101 Automotive Lemons”, and is included along with such automotive abominations as the Trabant, Yugo, Edsel, Gremlin, and Morris Marina, as well as the later Pontiac Astek, which was that company’s swan song too.

However, I will not take a position as to why the Hillman / Sunbeam Imp was not the success that the Mini and the Beetle were in their day. Instead, I will but outline the reasons most often given by those most familiar with the story, and let you draw your own conclusions.

At a first glance the answer seems simple. Turns out, many believe that the car was unreliable for the first year or two after it was introduced because Rootes Motors Limited, the company that designed and built the car, did not do enough testing to eliminate the bugs before putting it into production – and that’s possibly the case, but there appears to be more to it than that.

Other contemporary sources say that the Imp’s all-alloy, dry-sleeved engine was cutting edge, and that the company had not produced an aluminum engine before, and had not fully appreciated the problems inherent in them. In fact, all-aluminum engines were just being tried in the United States in the late 1950s too, and initially the alloys they used were less than optimal. In fact, the much later Chevy Vega also suffered mightily thanks to its all aluminum engine.

Typical Imp motor problems were oil leaks, warping and overheating. And there were other issues too, such as transmissions that were not up to the job. But on the plus side, the engine was a derivative of the illustrious Coventry Climax four-cylinder power plant that had distinguished itself in racing with Lotus, as well as other marques. It was light, small, and powerful, and exhibited a great deal of potential, even if it was not particularly long-lived. After all, engine doesn’t have to be that long lived for racing.

The Rootes group, who included Hillman, Singer, Sunbeam, Talbot, Commer trucks and Humber, were headquartered in Coventry, England, and had already started preliminary design work on the prototype for the Imp the year before the Suez Canal crisis, when Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalized it, sparking a conflict with Britain and France, and closing the canal from October of 1956 until March of 1957. This stifled the flow of petroleum to Western Europe from the Middle East during that time.

Click here for period Hillman Imp video

In Britain, this meant fuel rationing and higher prices. The situation shocked the British carmakers into action to develop a new generation of small economical cars for the masses. The Morris Minor had been around since 1948 and had sold well internationally, but it was becoming dated, so Morris started development on the Mini, and at the same time the Rootes group, who had been producing larger more expensive cars up until then, placed its emphasis on the Hillman Imp, later also badged the Sunbeam Imp.

The parameters established by the design team—consisting of Michael Parkes, project engineer, and Tim Fry, coordinating engineer—were:

- The car needed to accommodate two adults and two children.

- Performance requirements were that the car must be able to do 60 miles per hour, and get 60 miles to the gallon of gas.

- A rear-engine configuration was agreed upon.

- The car needed to be fun to drive.

All of these goals were met except the 60 miles per gallon of petrol. That would have been impossible without terminally sacrificing performance.

And then while the Imp was being readied for production in the early 1960s, the British government stepped in with a much-needed investment to build a huge, modern assembly plant at Linwood, Scotland, near Glasgow. The reason for that was — with the decline of ship building in the late ’50s — there was heavy unemployment in the area. Rootes happily agreed to the deal, though it had its drawbacks. The most significant being that the assembly plant was 350 miles away from the main Rootes manufacturing plant in Coventry, north of London.

Click here for video history of the Hillman Imp

There are also those who say the reason for the poor quality of the first year or two of Imp production was a lack of skilled craftsmen because the area was full of shipwrights and sheepherders who were not experienced in the construction of automobiles. However, I would argue that is nonsense based on my own experience working on the Ford merry-go-round about the same time as the Imp production began.

Click here for video on the history of the Imp’s Scottish factory

Like Ford, the Hillman assembly plant produced one car a minute when everything was running properly, and the assembly was broken down into tasks that could be accomplished in that amount of time. I was 19-years old when I worked at Ford, and I had virtually no previous automotive experience.

I put the passenger-side front fenders on Falcons and Fairlanes back then, and it took no more than half an hour for me to learn my job. Quality and precision were not part of the assembly line vocabulary. Good enough was the name of the game. After a few repetitions, anyone could do the job without a glitch.

It was not skilled labor. You got a 15-minute break in the morning and the same in the afternoon during which a relief man would do your job. The relief man was usually a little older and more experienced, but he could do all the jobs.

Another big problem Rootes faced at the assembly plant in Scotland was that the supply of parts from Coventry needed to be continuous, compendious, and on time, which is more complicated than it sounds. If the installer of the clutch for example, ran out of clutch assemblies, he couldn’t do his job, and then the fellow who installed the transmission could not accomplish his task, and so on for the fellow putting in the driveshaft.

The whole assembly process would collapse like a row of dominoes, and if they attempted to keep the line going, they would end the day with hundreds of incomplete cars sitting to one side that would have to be completed by hand.

Management always shut down the line instead, when parts were missing. And with the Imp, one especially poorly thought out logistics problem was that —though the engine blocks were cast in Scotland — they were then shipped south to be machined and assembled in Coventry, before being returned as finished engines to Scotland, making a 700-mile round trip in the process.

Supply snafus, along with strikes and shut downs on the part of the labor force, added up to 31 work stoppages in the first year of production alone. This, combined with the fact that they were building an all-new car, inevitably caused unforeseen challenges and quality issues that needed time to unsnarl.

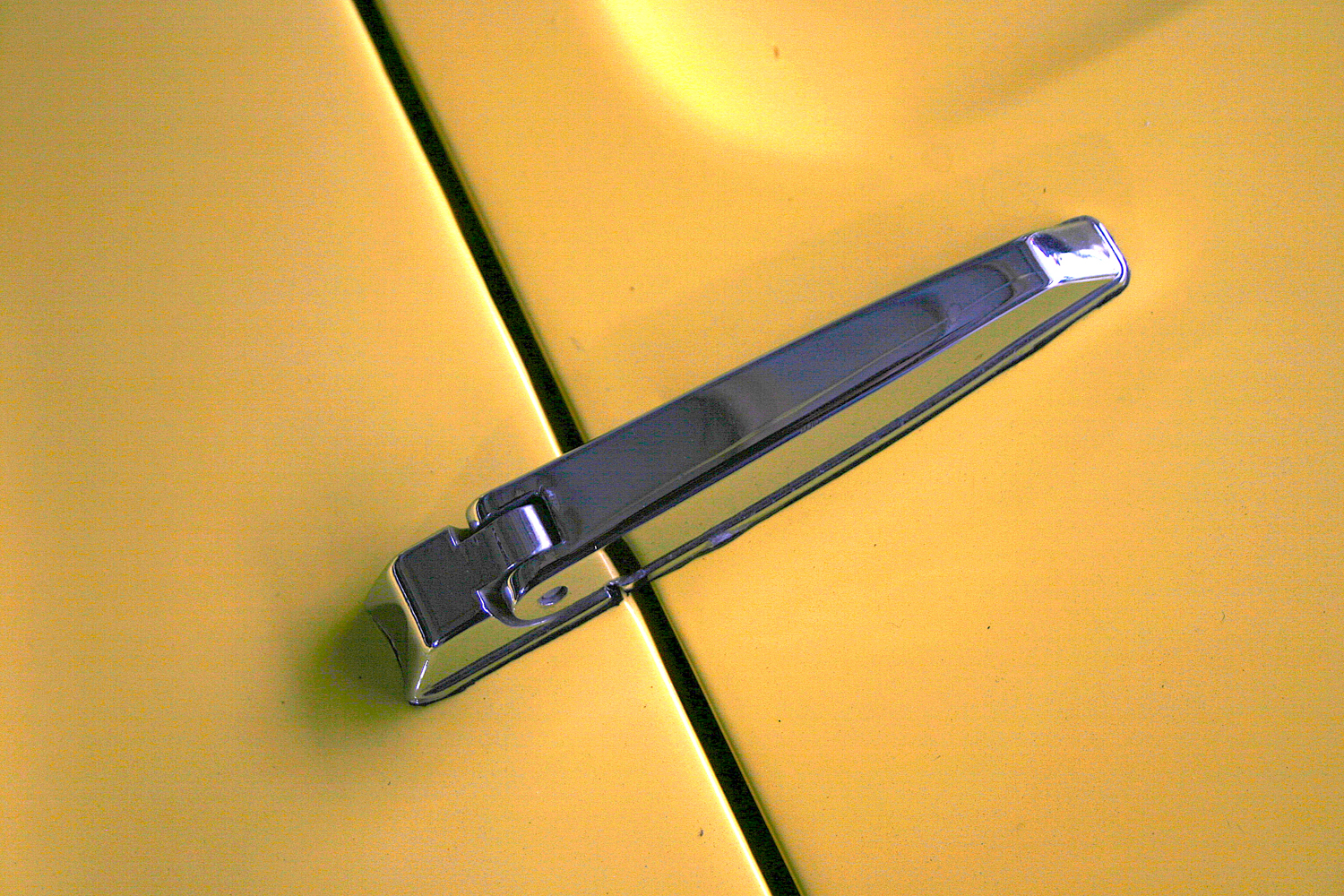

And, unfortunately, not all of the problems had been solved even six years later when our Sunbeam Imp was assembled from a knockdown kit at the Todd Motor Industries plant at Petone, New Zealand. As you can see in the photo nearby, the fit and finish of the passenger side door on Tagg’s Imp is crude to say the least.

Those are the primary reasons most authorities posited as to why the Hillman / Sunbeam Imp was not the success it should have been, which is unfortunate because the car’s design and engineering is good, if basic. To design a car for the economy market that has only what is strictly necessary, is actually more difficult than coming up with an expensively equipped car with a big budget at your disposal. Nothing in a basic car can be finessed. If anything is marginal, it becomes painfully obvious sooner rather than later.

Jeremy’s Imp is roomy, reasonably fast, and economical at 34 miles per gallon. Many of its features are subtle but practical, such as the openable back window that allows you to haul long items when necessary, and provides air circulation on warm days. Also, though the backseat is small, it is not as cramped as that of a Beetle, and it can be folded down to provide a commodious cargo space.

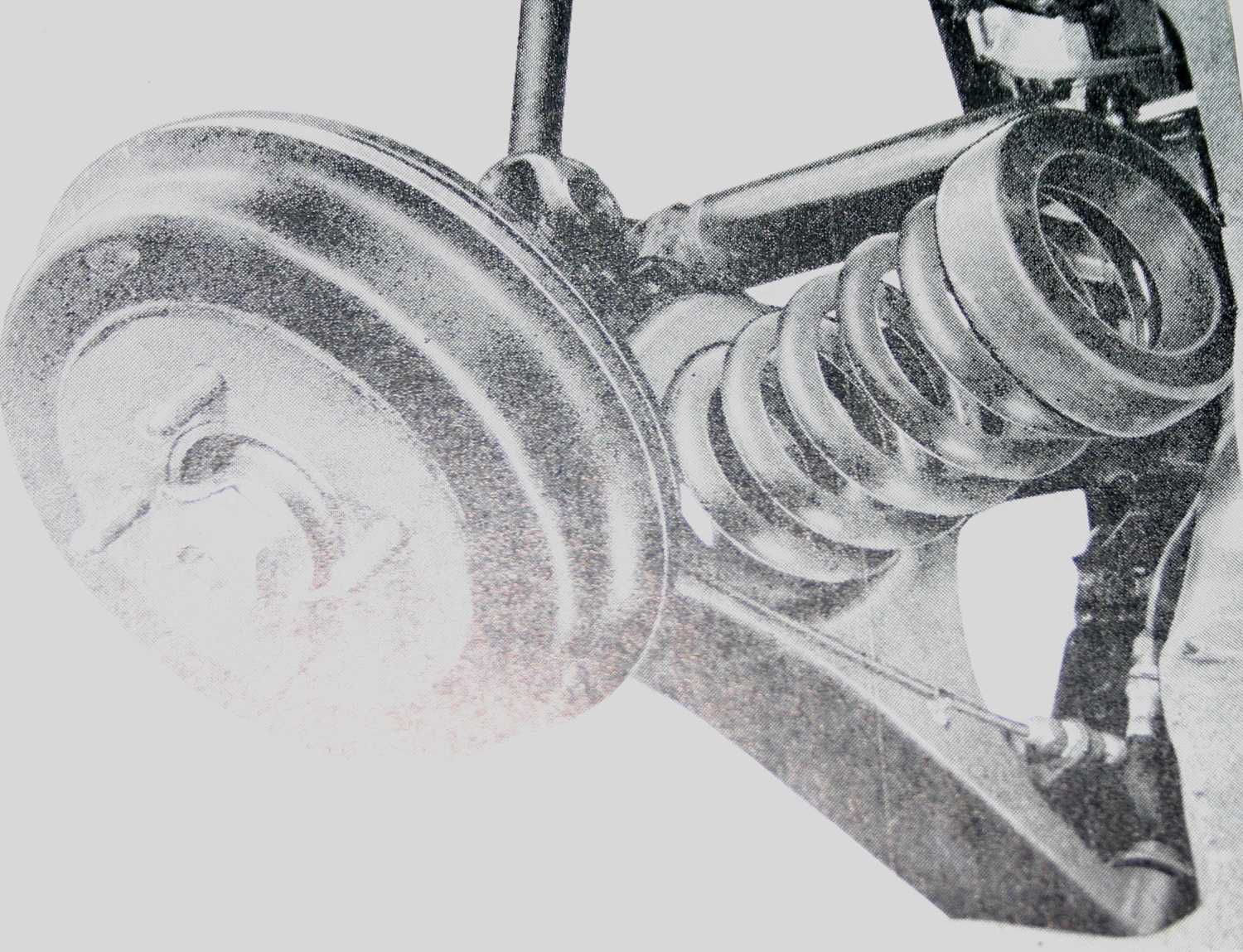

Along with its lightweight, peppy power plant, the Imp has coil-over springs and independent suspension all around, as opposed to the rather dangerous swing axles of the Beetles and early Corvairs of the era. The Imp doesn’t look that impressive, but its excellent engineering and minimum weight adds up to a great deal of potential. And, in 1965, the Rootes group took advantage of these virtues with the Hillman Imp Rallye 1000 version of the little sedan.

Initially “Works” Imps were prepared by the Rootes Competition Department for the company’s own drivers such as the legendary Rosemary Smith, and they were equipped with a 998-cc version of the standard engine. They were able to obtain this displacement by boring away the existing sleeves completely and inserting ones with bigger bores, but they left the stroke unchanged.

At the Motor Show in 1965, they announced that this engine that had achieved such remarkable racing results that year would be available next year in an Imp model called the Rallye. This offering included a tachometer, a bigger radiator and oil cooler, two Stromberg carburetors, bigger valves and dual valve springs. The hotter engine also sported a custom exhaust manifold and a compression ratio of 10.5:1, which was right at the limit of what could be done with ordinary pump petrol.

The suspension was also altered significantly, with bigger springs and shock absorbers, making the car’s already good handling even better. The engine tweaking netted them 70 horsepower, and gave the Imp a top end of 93 miles per hour. Of course, the Imp Rallye was not originally intended for road use and was only built to order. Vary few Rallye Imps still exist, and the few that do command a good price, though there are knock-offs that buffs have built that can be had for less, and Imps are still commonly rallied at local events.

The rarest of the Hillman line is Jeremy Tagg’s 1970 Commer Imp Van. And it is beautifully and accurately restored as well. It was the last and best of a line of small vans based on the Imp sedan introduced originally in 1965. It was ideal for economical around town deliveries, but only 18,194 of them were built. It used a lower compression version of the 875-cc engine making a rather agricultural 35 horsepower, and was geared lower in order to lug cargo up hills.

The Commer was an austere little vehicle originally offered with only one seat, one sun visor, one vent window, few gauges and no sound deadening, but Jeremy’s later model has a few more creature comforts. In addition to the detuned engine, the Imp Van also featured wider heavier wheels, stronger drive shafts and bumpers, and a thicker clutch lining. Even the exhaust tip was turned downward to avoid soiling the uniforms of those who made deliveries.

Tagg’s Commer is also a rolling advertisement for his business, which is installing new automotive glass in classic and vintage vehicles. He has even fabricated or procured glass custom curved to order, and he works on site for collectors if necessary. And his van is ideal for this purpose. It is small, economical, and yet roomy enough for a big windshield and his tools, plus it merely sips fuel.

Jeremy has always had a soft spot for the Imps after obtaining one as a youth and learning to work on it. He is now in the process of building an all out rally car from another sedan, using a hot, super-tuned engine, heavy duty suspension and a front mounted radiator for extra cooling. He says that parts are still available from the U.K., and there is a good club for Hillman fanciers in New Zealand too.

On our spin out of the suburbs and into the countryside the little Imp sedan does well and is truly fun to drive, fulfilling the goal of its designers. It pulls hills and keeps up with contemporary traffic just fine if you keep the rpms up, and its steering is light and responsive. The longevity of the earlier models may have left something to be desired, but the little machine has all the makings of a great local rally, and amateur airport hay bail racing entry.

But then that is pretty typical for a lot of the small basic cars from around the world over the years. In Germany, nobody drives a Trabant back and forth to work anymore, but they are a favorite with amateur racers. And in California I know a fellow who builds and races Yugos! He was into Fiats in a big way, but the Yugo is cheaper to buy, and just as fun. And down in Brazil they used to play polo driving Renault Dauphines with their doors removed.

Most of us are not really up to piloting Corvettes and Ferraris, but we can have a very good time in a simple inexpensive little car with a little tweaking and tuning. And while none of these small minimal cars were renowned for their long-term reliability, they are known for being easy and cheap to fix and fun to drive.

The demise of the British auto industry has been debated for years, and the consensus is that fierce competition, labor problems, and a lack of innovation and investment on the part of management ultimately brought it down. Today, even Rolls-Royce is owned by BMW, and Jaguar is owned by Indian automaker Tata. Turns out that Britain still assembles a large number of automobiles, but mostly for foreign-owned companies.

Thankfully, Britain’s glorious automotive past is being preserved by buffs like Jeremy around the world, and rightly so, because the UK has produced so many magnificent and pivotal cars in automotive history. Over a cup of tea I thank Jeremy for the opportunity to explore an unfamiliar niche in automotive history, and spend the day with an Imp.

SPECIFICATIONS

Manufacturer: Commer Cars, Ltd., a division of Rootes Group

Country of Origin: Scotland (assembly) and England

Drivetrain Configuration: Rear-engine, rear-wheel drive

Engine: Water-cooled inline-4, OHC, 875cc, 36bhp

Transmission: 4-speed manual

Top Speed: 72 mph

Years of Production: 1963-1976

Number Produced: 18,194

Original Cost: £441 (approx. $1050 USD

| Imp Sport | |

| Bore | 2.67″; 68mm |

| Stroke | 2.37″; 60.3mm |

| Capacity | 53.41cu.in. = 875cc |

| Max. bh power (SAE pk) | 55 @ 6,100 rpm 50@5800rpm (DIN) |

| Max. torque | 7.7 @ 4,300 rpm |

| Camshaft. Valve lift | 0.310″ |

| Overall top gear ratio | 4.138 to 1 |

| Brakes front | Servo assisted drum type two leading shoe |

| Brakes rear | Servo assisted drum type leading and trailing shoe |

| Weight unladen | 1,633lb. = 750 kg. |

| Tyres | 155 x 12 |

| Petrol use | 1 liter : 12km |

| Top speed | 90mph = 145kph 30, 56, 82mph through the gears |

| Cruise speed | 130kph |