Unlike Vintage Racecar’s editors I don’t spend my working life thrashing the pants off other people’s rare and priceless racing cars, mores the pity, so when the offer came to get intimate with two Italian models I jumped at the chance. It was in Sicily during the centenary celebrations for Giro di Sicilia-Targa Florio that these two beauties presented themselves, one from the Ferrari stable the other from Alfa Romeo both with such strong links to the Targa Florio that I couldn’t believe my luck, not only to ride in them, but actually at the home of this great road race as well.

First I have a confession to make, it turns out that Jim Glickenhaus and I have been in love with the same Italian beauty for the last forty years, but while I was loafing around the motor racing circuits of Europe Jim spent his time wisely by working hard and has become a very successful Wall Street investment banker. Not to difficult then to realize who ended up with the girl, and her name you ask? It’s Ferrari P3/4….

James M Glickenhaus has a stable of historic racecars and he uses all of them on a regular basis, not on the track mind you, but driving them on the highway! Jim had brought three of his Ferraris along to grace the Targa Florio centenary celebrations with pride of place going to his P3/4, chassis no 0846. This car started life in 1966 as a P3; at the end of the year it was upgraded to P4 specification and used by Ferrari as their test-bed for the 67 upgrade, it then went on to win that year’s 24-hr race at Daytona piloted by Lorenzo Bandini and Chris Amon. She was next used in the 67 Targa Florio by Nino Vaccarella where, after setting the fastest practice time, he crashed out of the race at Collesano village on the second lap. 0846’s last race was the 1967 Le Mans 24hr this time it was Chris Amon and Nino Vaccarella who shared the drive; unfortunately they had to retire the car when a blown tyre caused it to catch fire. After this 0846 was returned to Modena where the decision was made not to rebuild her and the chassis eventually ended up in a Modena scrap yard.

Thirty three years later Jim bought a P4 from British Ferrari specialist David Piper, he was told that it had been constructed in 1974 using parts obtained from Ferrari with the chassis being fabricated by the original manufacturer using Ferrari’s plans; once this car was in the USA Jim’s team, John Hajduk Jnr and Sal Barone, started a ground up rebuild. Once down to the bare bones, and after careful examination, the chassis revealed some secrets, it had in fact started life as a P3 and had been upgraded to P4 specification later on, also there was clear evidence of repairs to the tubing consistent with Vaccarella’s crash and the Le Mans fire, so, after yet more detective work, Jim has come to the conclusion that from time to time some Italian chassis manufacturers must frequent Modena scrap yards.

“Molto elegante” is the best phrase to describe the P3/4, perhaps the most beautiful and certainly the most curvaceous sports-racing Ferrari ever made, the 1966 P3 was a direct descendent of the 1963 250/P with its V12 mid-engine lay out. Constructed in response to the challenge from Ford for the 1966 World Manufacturers’ Championship Ferrari made a new lightweight 3,967cc V12 four camshaft engine, with Lucas fuel injection and Marelli coil ignition, thus saving 65 lbs compared to its predecessor. Piero Drogo designed a voluptuous body to clad the all new multi-tubular frame that incorporated some of the alloy body panels as stressed members. This new model proved to be very fast, but unfortunately not fast enough as Ford took the 1966 championship.

For the 1967 season Ferrari upgraded their 330 prototype and although outwardly resembling its predecessor a host of the major changes were hidden beneath that shapely bodywork. An all new 3,967cc V12 alloy blocked engine, utilising Ferrari’s F1 36-valve head design (two inlet, one exhaust, per cylinder), was at the heart of the car nestling in a redesigned tubular chassis. With this new cylinder head and by moving the fuel injection and spark plugs to between the camshafts Ferrari managed to push the V12’s power up by 30bhp to 450 at 8000 rpm, this beautifully engineered unit was then mated to an all new five-speed gearbox. With upgraded outboard Girling disc brakes and new 15 inch wheels the P4 weighed in some 400 lbs lighter than its predecessor. This combination of improvements proved to be crucial enabling Ferrari to snatch the 1967 championship from Porsche at the last race of the season the BOAC 500 held at Brands Hatch.

Standing in the pits at Siracusa’s Autodrome on a hot June afternoon is Ferrari P3/4 Spyder no.0846 surrounded by a group of admirers among which are Nanni Galli and Gerard Larousse. Jim Glickenhaus comes up to me and starts to apologise and I think that’s a ride in my dream car I nearly had! Jim continues “I had thought it would be good for you to have a few laps with Nanni but you’ve been out-ranked as his wife wants to go with him, so I’ll take you instead”. Well I see what he means, but as this is the culmination of a forty year love affair I’m hardly disappointed!

The tiny passenger door is swung open and I climb over the wide sill and slither down into the left hand seat and strap in, as with so many sports-prototypes of this era the P3/4 is right hand drive in deference to the mostly right hand circuits that they were raced on. While Jim straps himself in the driving seat I survey the scene before me, rising in front, like two beautiful Italian bosoms, are the wheel arches with little else of the forward bodywork visible from the cockpit, the huge curved windscreen does distort the forward view slightly but Jim assures me “you soon adjust to it”. Set out in a binnacle in front of the driver are a large rev-counter flanked by the oil and water gauges. Jim switches on the ignition, pushes the starter button and the already warm V12 bursts into life, with it comes the sound of hundreds of precision parts whirring and meshing together 12inches from my right ear, not as loud as you might expect and a completely different noise from that outside the car. As Jim engages first the Ferrari jerks forward straining at the leash, up comes the clutch and we trickle smoothly down the pit road all very well behaved for a sports racer, the car is de-tuned a little for Jim to drive her on the road and it showed, for the first 200 yards at least.

At the end of the pits we get an all clear from the marshal, Jim glances in my direction, I give him a thumbs-up and he hits the loud peddle, the acceleration is not violent, no slap in the back of your neck, but its rapid and I’m being squeezed harder and harder against the back of my seat. Siracusa is one of those rare left hand circuits and Jim lifts early for the first 180deg corner, as we exit on comes the gas and 0846 leaps forward with the back end just breaking away slightly, 600 yards down the track we speed through the a right-left flick with a little confidence lift just before the entrance. As we head for the second apex I realise that it disappears from view just at the critical moment courtesy of those voluptuous fenders. This complex is followed almost immediately by a slight right hand sweep and then 800 yard straight at the end of which is a left hand open 45deg double apexer, Jim now has her in 5th and we approach at about 150mph, breaking for the corner the old girl shows her breading and slows to under 100mph quickly and smoothly with no fuss. With a slight movement of the wheel we are set up, she’s very pointy and turns in without a problem, running out slightly after the first apex again Jim tweaks her left for the second one, then onto another short straight before it’s time to head back in the opposite direction via a long 180deg left hander.

Accelerating back along a ¾ mile straight I’m surprised just how smooth the ride in this car is, yes the suspension has been softened for Jim’s Sunday “road runs” but this doesn’t seem to have unsettled the car at all. Just over 170mph on the clock and on go the anchors to haul us down for the sharp left-right, right-left complex that leads onto Siracusa’s pit straight, the soft springing causes her to nose dive a little at first but she soon settles down and flicks through with accuracy and ease, I’m told “she does not respond well to sideways motoring, if you want to be quick set the car up early and come out tidy”.

We flash past the pits and my initial excitement gives way to awe, for the next few laps I imagine that slight and unassuming man, who has been with us for the last few days, racing this nimble thoroughbred around the fantastically torturous Targa circuit with its continuous undulations punctuated by 1000 bends, blasting through the villages to the sound of the crowd chanting his name “Vaccarella Vaccarella”. If ever a car was designed for circuit Piccolo Madonie this is it, power aplenty in a chassis with the agility of a polo pony. All too soon we’re flagged in as it’s time Mr & Mrs Galli to take over then again there’s that glorious sound of the V12 reverberating around Siracusa.

Thirty five years before Vaccarella another small and slim Italian legend, Tazio Nuvolari, was tackling the Targa Florio in the ultimate sports-racer of the time, a car so desirable that race drivers would buy one out of their own funds in order to be able to compete with it, the Alfa Romeo 8C. Half an hour after my run in the P3/4 and standing out back of the Siracusa pits is the 1932 8C Monza of joint owners Graham Burrows and Peter Mann. I’m offered the job as navigator for the evening road stage from Siracusa to Catania because the Alfa’s very firm suspension is starting to aggravate Graham’s back problems, so he’s swoped to my hire car for the evening. Now you could feel very sorry for Graham until I tell you that after retiring from building a very successful chain of pharmacies he summers in Europe racing historic cars at places such as Monaco and the Nurburgring then winters skiing in Canada!

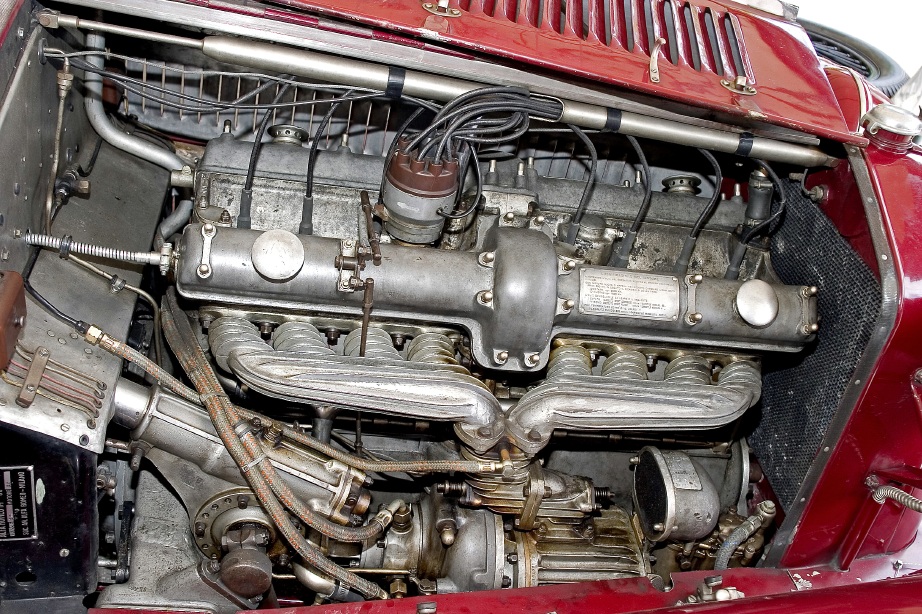

As a successor to his ageing P2 GP cars, which by 1930 were no match for the 2.5 Litre Maseratis, Alfa Romeo’s designer Vittorio Jano created the 8C 2300. Jano designed a completely new engine for the car, by carrying over the same bore and stroke (65X85mm) from the P2 but increasing the cylinders from six to eight he took the capacity up from 1750cc to 2336cc. Two four cylinder alloy blocks were mounted inline on a single crankcase, being separated by a central gear-train that drove the twin overhead cams ancillary pumps and a Roots-type supercharger. In joining two small units together Vittorio reduced casting faults and the resulting shorter camshafts minimised any timing problems caused by camshaft twist. Intended from the outset to use a supercharger the 8C displays one of automotives “works of art” its beautifully finned aluminium inlet manifold designed specially to dissipate the heat generated by that pressurised induction system, with the whole unit mated to a 4-speed “straight cut” gearbox via a multiple-disc clutch. The chassis by comparison was relatively simple consisting of two side rails joined by a series of cross members, with suspension using semi-elliptical leaf springs, front and rear, supporting solid axels dampened by lever-type friction units.

From 1931 to 1934 the 8C provided Alfa Romeo with a host of victories both in Grand Prix and Sportscar racing, the chassis was produced in three different lengths and clad in various bodywork configurations to suit the conditions under which it raced. Graham and Peter’s car is a Spyder Corsa built on the shortest chassis (2,650mm) this model being dubbed “Monza” honouring Nuvolari and Campari’s victory at the 1931 Italian Grand Prix. Nuvolari won the 1932 Targa Florio driving an 8C at an average speed of 79.26 km/h a record that remained unbeaten for the next twenty years, a testimony not only to the driver but also to his car.

Legends surround Nuvolari and one concerns that 1932 Targa victory, make of it what you wish, as they say “why spoil a good story by looking for the truth”. During the early 1930’s a fledgling Scuderia Ferrari were running the works Alfa team and Nuvolari requested from Enzo a very light riding mechanic to accompany him on the Targa Florio. Mr Ferrari came up with a young junior named Paride Mambelli and seated beside Nuvolari at the start of the race Paride was told by the maestro to duck under the scuttle when he shouted as they would be approaching a corner too fast and might turn over. After the race Mambelli was asked how he got on “Nuvolari started shouting at the first bend and didn’t stop until the last one”. The boy answered. “I was down at the bottom of the car all the time.” Well—–remember they did set a twenty year record!

Yet another right-hooker this time without even the vestige of a passenger door “Watch out for the hot exhaust running along the side there as you climb in, it doesn’t take any prisoners.” warns Graham. Once it the passenger’s seat I can see why Nuvolari wanted a small companion, all very cosy, the bodywork raps around your waist leaving your left arm free to rest on that red hot 2.5” exhaust. The smell of warm leather and petrol wafts around me, arrayed across the dashboard are a clock, oil pressure gauge and rev-counter on my side, with the driver having the benefit of the speedo and the fuel and water temperature gauges on his side, with that gorgeous bonnet disappearing into the distance it’s a bit like sitting astride a crocodile’s snout. Just by the left hand of the riding mechanic is a large brass handle, Peter (Tazio) Mann explains that I will be required, from time to time, to pump this in order to maintain pressure in the fuel tank so as to keep the Mernini carb well supplied with benzina “give a couple of pumps now” I’m told, as he climbs in next to me. No seat belt stuff this time and after a few in and outs of the pump by me Tazio Mann hits the starter and the 8C bursts into life. It’s immediately obvious that directions from the Road-Book will have to be conveyed by hand as the glorious roar from that open exhaust is completely deafening. Unlike modern machinery the 8C has a central throttle (brake to the right clutch to the left) “Makes heal toeing easier” shouts Peter, of course with a crash gearbox all changes, both up and down, need double de-clutching.

We head for the highway, on route our ear drums are assailed by that exhaust as we pass through Siracusa’s two exit tunnels, once were on the open road Tazio Mann gives the old girl her head, even from low revs the acceleration is impressive with Jano’s power plant feeling strong. As the speed builds with Tazio dancing across the peddles and up through the gearbox the limitations of a seventy year old chassis become obvious, over 40 mph the car reacts to every change in the road surface requiring constant adjustments to the steering. Soon the exhaust has heated the entire left side of the cockpit to the temperature of bread oven and no matter how I try I can’t avoid being roasted. An empty section of road opens up in front allowing Tazio Mann to put that central pedal to the metal, no need for a down shift as this engine has bags of torque, the straight eight surges on accompanied by the sound of the Roots blower doing its stuff. As we pass 60 the chassis finds it even more difficult to cope, at this speed bad bumps cause it to buck with the resulting jolt being transmitted through to the occupants backsides, if I had a pair of asbestos gloves I could hold on to the side panel but instead I slide across the bench seat and play “bumps a daisy” with Tazio. Steering corrections now have to be rapid and accurate, and with a considerable slipstream buffeting us I glance across to Tazio Mann who’s sawing away at the wheel to keep us on the straight and narrow, later he assures me that the steering is quite light for a car of this age, I look ahead again and realise our next little problem is coming up fast in the shape of a right hand bend. Stamping on the left peddle starts the deceleration process but with nothing like the efficiency of the power unit that got us up to this velocity in the first place, although sporting four huge aluminium drum brakes stopping is not one of the Alfa’s strong points. Fortunately the pilot is well in control and after some strong leg work an a lot of juddering we roar through the corner in a gentle slide, he later explains “ You need to throw her into the bends, keep the speed up and get the power on early otherwise she does tend to wallow into understeer.”

As the evening run progresses I sit there watching the front of the car twisting and flexing as that long narrow chassis tries to absorb the surface changes and again as my mind wanders to times gone by I’m filled with admiration, this time for Nuvolari and his contemporaries who raced these cars, throwing them around over dusty rutted roads for hours on end without power assisted brakes or steering to help them, with every gear change needing precision timing or they risked ruining the box. Eight laps of the 44mile Targa course, that even today bears more resemblance to a fairground switchback than a racing circuit, in a car like this over roads that were little more than cart tracks is a feat that is almost impossible to imagine. No wonder Nuvolari was shouting all the way.

Tazio Mann is also shouting, not because he’s lost control but to wake me from my daydreaming, he’s wanting more fuel pressure and some directions for a roundabout 100yards ahead, two embarrassing circuits of that roundabout later I sort the Road-Book and get us headed on the correct road for our overnight stop. In another forty five minutes, hot, dusty and dry mouthed we sweep onto Catania’s seafront to be greeted by hundreds of spectators who have turned out to cheer the cars from the Giro di Sicilia. This is what it must have been like for Vaccarella or Nuvolari, Italian heroes racing great Italian cars on Italian soil, for the Italian’s it doesn’t come any better than that, and you know after the last few hours I’ve just spent in Sicily I must agree with them. Both vehicles represent the pinnacle of automotive design in their time; both are fast, even by comparison with today’s road cars, but the Ferrari demonstrates more that anything how chassis technology had advanced in thirty five years.

Last word—The thought of Nuvolari averaging just under 50 mph–in that car–on that circuit–for a little over 350 miles– leaves us speechless, all of us that is except the great man himself (according to the legend anyway)!

Great article.