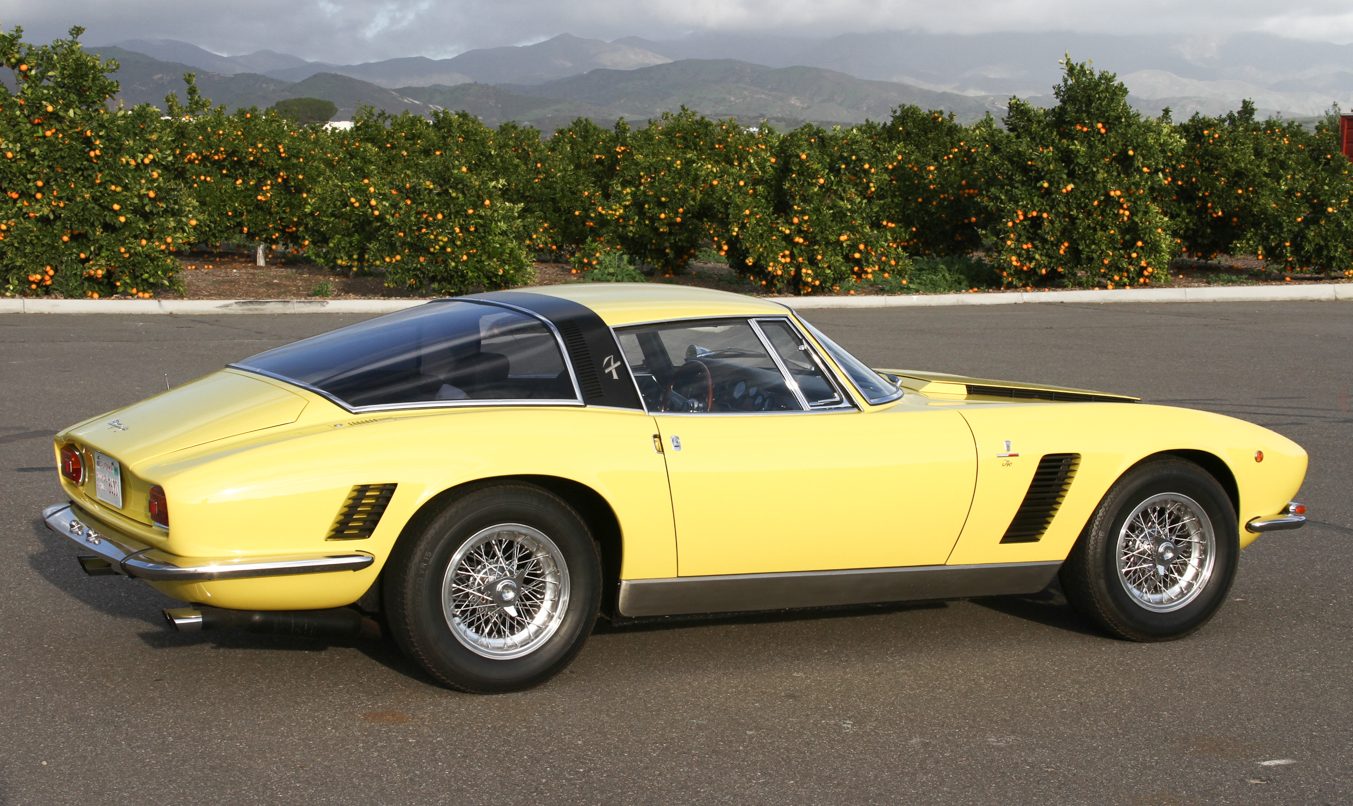

I found out from Murray’s chief restorer Derrick Boycks that we were looking at a 1968 Iso Grifo. I had seen photos of Iso Grifos, but had never beheld one in person that I could remember. Dave and I got to work on our assignment to do a report on Don’s Sebring Sprite, but vowed to come back and drive the Grifo as soon as we could arrange it. We returned some weeks later and were handed the keys to this automotive masterpiece.

I bend down and press the subtle flush-mounted combination button and handle to open the door of this long, low, lovely machine and slide into the driver’s seat. The cockpit is perhaps a bit shy of legroom for someone my height, but is otherwise roomy and ergonomically well laid out, not to mention handsome and elegant. There is otherwise nothing remarkable about the interior except for the obvious attention to detail and craftsmanship that went into it.

The dash features a complete array of round black business-like analog gauges that are large and easy to read. Also there is a line of toggle switches that look no nonsense and purposeful. In fact, except for the wood inlay in the dash, the instrument panel would be right at home in Italy’s front line World War II Macchi Folgore fighter plane.

I buckle up, let off the hand brake, twist the key, and am treated to the thump and roar of a 427-cubic-inch Chevrolet big block that upon receipt at Iso was disassembled blueprinted, and tweaked to perform as it was designed to do. This is one big barroom brawler of a power plant in a beautifully tailored Italian suit.

As the gauges jump and dance I begin to feel right at home. I am aware of what is under the hood, but I still somehow half expected the scream of a smaller, more highly stressed engine, based on the Bertone styling. For me, there is nothing like the rumble of a big American V8 to reassure me that I have more than enough low and mid-range torque and horsepower to overcome any likely challengers.

I depress the clutch and pull the Muncie Top Loader four-speed into low as Derrick opens the big side door of the building. Inside the building, the Grifo’s basso profundo big block grumble is compelling, but once outdoors, it diminishes to a discrete reassuring rumble that lets you know you have plenty of power on hand, but it would not upstage a conversation with a passenger or a little music from the radio.

We head over to a huge fairgrounds parking lot where I take the car up through the gears. I soon discover that for anything other than the Autostrade, you would never need fourth gear. Acceleration is impressive even though the car is geared for high-speed touring, and as a result it is not as brash and boisterous as a contemporary Corvette. However, the big block Grifo, when race-tuned properly could (and did) hold it’s own on the track, even though it was primarily designed for luxury touring, and looking ever so cool while doing so.

Murray’s Grifo is one of only 65 built with the 7-liter big block, and another one of these proved itself back in the day piloted by Bob Bondurant, who wrung a top speed of 186.4 miles per hour out of a Series II Grifo, which was a first for a production car at the time. Gearing in the Iso Grifo is tall, in order to achieve such high top speeds, and even the earlier models with the 327 Corvette engine could do 68 miles per hour in first gear.

Steering is heavy when going slow, but lightens up at driving speeds. Cornering is predictable and old school due the Grifo’s heavy front end and light rear. This makes the car quite predictable if one learned to drive in American cars of the ’50s and ’60s as I did. In that case, you know to steer into a skid to control the back end step out the way modern drifters drive. Of course, you scrub off speed when you do that, but that is infinitely better than having the front end come loose. In that situation, you are just along for the ride until you collide with something.

So how did this magnificent creation come into being? Well, it came from a rather unlikely beginning. Iso opened in Genoa, in 1939, and manufactured refrigerators. Owner Renzo Revolta later moved the operation to Bresso in 1942. Revolta came from a family of successful industrialists but his company was compelled to go into war production. And then after the devastation of World War II, Iso was refounded as Iso Autoveicoli S.p.A., in 1953, as the company changed its focus to motorcycles and scooters.

Iso motorcycles were well engineered and constructed, and had a good reputation, though they were a bit pricey for the times. And then, as time passed and Europe continued to recover from the war, people started looking for transportation that would get them out of the weather and provide a modicum of comfort for the driver and a passenger. The challenge was that the new vehicle needed to be inexpensive to purchase, and economical to operate because gasoline was in short supply. Also, it needed to be suited to Europe’s city traffic and narrow streets.

The solution was the Iso Isetta, or little Iso. It was powered by the company’s 236-cc, two-stroke, two-cylinder motorcycle engine, and had only one door in front like a refrigerator. In fact, it has been said the Isetta was basically a cross between a motorcycle and a refrigerator on wheels, with its single front opening door. But that allowed you to park it nose first and just step out onto the sidewalk.

This was a convenient feature for Europe’s ancient cities, but a friend of mine long ago who had one in the States drove his over to a baseball field to watch his son’s Little League game. Problem was, when it came time to leave, it wouldn’t start, and he couldn’t get out because the door was up against the chain link fence. He had to yell for help until a Good Samaritan came along and pushed the Lilliputian auto back far enough for him to exit it.

In truth, the Isetta looked much like an enormous egg stood upright, with trouser buttons for wheels. The minuscule machine could accommodate two people, but you would want to know your passenger pretty well. But the little cramped micro car would get you from A to B in inclement weather without risk of hypothermia.

The tiny Iso Isetta caught on in Italy, and soon BMW in Germany bought the rights to build it as well. However, they reengineered it to use their BMW one-cylinder, four-stroke, 247-cc motorcycle engine, and sold them all over the world, including here in the United States. The Isetta was a bit petite for most Americans, but it sold well globally, and was manufactured under license in several other countries as well.

It was from this humble beginning in the automobile business that Iso went on to build some of the most beautiful high-performance touring cars of the ’60s. You could say that they went from the ridiculous to the sublime, with no in between. The transition to the sublime later cars happened primarily because of the legendary palace revolt at Ferrari in 1961.

The problems started with Enzo Ferrari’s son Dino’s (short for Alfredo) death due to muscular dystrophy in 1956. He was an automotive engineer, and the apple of his father’s eye. At his passing, il Commendatore became inconsolable, and withdrew from the daily management of the company, resulting in his wife Laura becoming more involved.

Laura’s meddling in technical affairs did not agree with Ferarri’s talented team of designers and engineers who were used to a bit more respect and freedom, and so they threatened to resign. At that, il Commendatore called them into his office for their regular weekly meeting, gave his usual briefing, and then had an assistant hand out envelopes to those who were involved. It contained a week’s pay and a dismissal notice.

We are talking about the likes of Carlo Chiti technical director, Giotto Bizzarinni, head of engineering, Racing Director Romulo Tavoni and Commercial Director Giroamo Gardinini. It was as if the great Cosimo De’ Medici had told Michelangelo, Da Vinci and Raphael to buzz off, back in the Renaissance. But Enzo’s loss was Iso’s gain.

Bizzarinni had been working on the fabled Ferrari 250 GTO when Ferrari fired him, and as a result, some of the engineering from that car ended up in his own car called, aptly enough, the Bizzarini. And later it influenced the Iso Revolta GT styled by Giorgetto Giugiaro at Bertone. The Iso Revolta GT was a beautifully styled, four-seater sporting a Chevrolet 327-cubic-inch Corvette V8 and De Dion rear suspension. It sold well, with 799 produced.

Bizzarinni had consulted at Iso prior to this, but went to work for Renzo Revolta in 1964 and helped develop the aforementioned Iso Revolta and later both the A3/L (the L stands for Lusso, or luxury) as well as the A3/C racing versions (C is for Corso) of the Iso Revolta that came with alloy bodies and no dash panel or much of an interior. The A3/L luxury cars featured pressed steel monocoque bodywork on a pressed steel frame.

However, just as with the great masters of the Renaissance, the masters of the golden age of Italian auto design were a somewhat volatile bunch. Bizzarrini and Revolta went their separate ways in 1965 and that meant that the Grifo GL and the competition Bizzarini A3/C ended up with separate production, with Bizzarinni refining the racing A3/C for which he was primarily responsible, into the Bizzarinni 5300 Stradas and Corsas.

Upon the death of Renzo Rivolta, in Milan in 1966, his son Piero became Iso’s CEO at the tender age of 25. Under Piero’s leadership, Iso built the S4 2+2, later dubbed the Fidia, which was touted as the fastest four seats on wheels in an advertisement in 1967. Ghia designed the bodywork for the Fidia, which sported the GM 427 high torque marine engine, as did the 2+2 fastback Coupé Lele (1969) with body designed by Bertone, intended as the successor to the IR 300.

The early Grifos, (Grifo is Italian for Griffin, which was a creature from Greek mythology with an eagle’s head, wings and front legs, atop a lion’s hindquarters) were built using the Chevrolet 327 for power, coupled to a Muncie four-speed and a De Dion rear end with Jaguar disk brakes, making for a fast, superb handling machine. Don Murray’s later Lusso was even faster because it is equipped with Chevrolet’s 427 big block power plant. And a few of the later series II Grifos were even fitted with the bigger 454.

Don Murray’s Iso Grifo debuted in 1968 and came with the L71 427 big block engine. The bigger power plant required a number of changes to the chassis and bodywork in order to fit. The engine compartment was enlarged, the chassis was reinforced, and stronger motor mounts were added. In addition, a broad pagoda style air scoop, also referred to as a penthouse, had to be added in order to accommodate the increased height of the engine. The result was a grand touring car with an unusual hood, and a top end of 186 miles per hour.

In 1970, Iso came out with the series II Grifo that had updated styling and retractable headlights, as was common at the time. It was powered by a Chevrolet 454 7.5-liter V8, which made for even more potent acceleration, though Iso switched to the Ford Boss 351 engine in 1972 as the demand for big engine gas-guzzlers subsided.

The Iso Rivolta plant relocated from Bresso to Varedo in 1972. And, in addition to Grifo Series II, Fidia and Lele, the mid-engine Iso Varedo was created there, with the chassis engineering coming from Bizzarinni with styling by Ercole Spada. Unfortunately, only one prototype was built before Iso went bankrupt in 1974.

Adding a Grifo to your collection would take some doing, because so few were built, and even fewer survive. Many were sold in Germany where they could be driven the way they were intended on the Autobahn, while quite a few of them made it to this country. A paltry 32 Grifos were built with right-hand drive for the British Commonwealth countries.

Adding an Iso Grifo to my collection is entirely out of the question unless they could knock a couple of those zeros off of the current auction prices. An impeccable example such as Murray’s would fetch close to half a million dollars – in the event one should come up for sale that is. Alas, my tour and test drive, like all good things, must come to an end.

Dave shoots a few more moving shots, and we drive the Grifo back to Murray’s collection. I take it around to the big side door and hand it over to Derrick to pull it back into its place of honor in Don’s collection. We chat over a cup of coffee, I take a few notes, and then we get back on the 405 and settle into the modern real world of slow traffic, impatient drivers, and a long drive home.

SPECIFICATIONS

| Manufacture | Iso Autoveicoli S.p.A. |

| Production | 1963–1974 |

| Designer | Giorgetto Giugiaro at Bertone |

| Body and chassis | |

| Body style | 2-door coupe |

| Layout | FR layout |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | · 5.4 L Chevrolet 327 OHV V8

· 5.8 L Ford 351 OHV V8 · 7.0 L Chevrolet 427 OHV V8 · 7.4 L Chevrolet 454 OHV V8 |

| Transmission | 4-speed Muncie or 5-speed ZF manual transmission 3-speed automatic (on request) |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 98.4 in (2,499 mm) |

| Length | 174.4 in (4,430 mm) |

| Width | 69.7 in (1,770 mm) |

| Height | 47.2 in (1,199 mm) |

| Curb weight | 3,150–3,550 lb (1,430–1,610 kg) |