It was possibly the greatest automotive marketing slogan ever – “Ask the Man Who Owns One.” Packards were such high quality, reliable cars that asking someone who owned a Packard was sure to produce a very complimentary reply. Throughout much of the company’s history, its cars were considered among the best, if not the best, automobiles available in the world. Sadly, it was mostly poor decision making by the company management that resulted in the demise of Packard.

Creation and Rise of Packard

One way to tell the story of Packard is by focusing on the people who were most involved in the decisions made about the company. The first of these people was James Ward Packard, for whom the company was named. Packard headed the New York and Ohio Company, a manufacturer of electrical equipment in Warren, Ohio. His personal involvement with an automobile came with he bought the 13th auto built by Alexander Winton in Cleveland. That purchase, on August 13, 1898, resulted in an unsatisfactory experience for Packard. The car broke down repeatedly, leading him to return it to Winton. During the argument that followed, Winton challenged Packard to build a better car. It was a challenge Packard undertook.

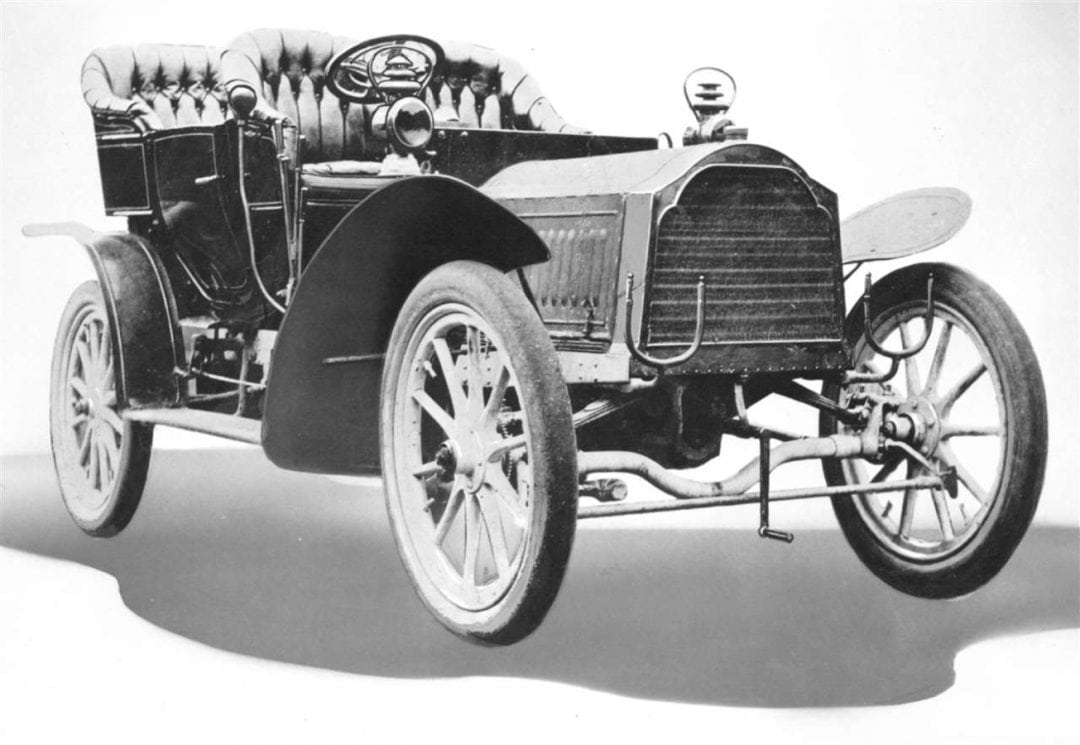

Packard was a mechanical engineer who graduated from Lehigh University in Pennsylvania, so Winton’s challenge was one he believed he could successfully undertake. Together with his brother, William Doud Packard, and two men he hired away from Winton—George L. Weiss and W.A. Hatcher—Packard designed his first automobile. The first Packard, the Model A, appeared on November 6, 1899, financed by the Packard brothers and Weiss. The Automobile Division of the New York and Ohio Company was formed in December of that year. The company would be reorganized and the name changed over the next few years, first to the Ohio Automobile Company and, in 1903, to the Packard Motor Car Company.

The Model A was a motorized buggy. It was a single-seater with a tiller and tall wire wheels. It was powered by a 12-hp horizontal, single-cylinder engine located under the seat driving the car via a chain. There was at least one innovation on the Model A – an automatic spark advance that Packard patented. It would be the first of many innovations introduced on Packard automobiles. That first car was sold to a neighbor for $1250, providing funds for the construction of additional Model A Packards. One of those was driven by Packard and a passenger on a 13 ½ hour drive to Buffalo, New York – quite an adventure at the turn of the century.

Packard built three “carriages” for the first New York Auto Show in 1900. The cars were not only displayed, but their performance was exhibited on a track where the cars threaded a number of obstacles. It must have been a convincing display because all three cars were sold – one to William Rockefeller (brother of John D.) and the others to Hollis Honeywell. That success led to more innovation, and in 1901 Packard replaced the tiller with a steering wheel, becoming an early adopter to use the steering wheel. Packard also patented the H-pattern shifter.

Arrival of Joy and Departure of Packard

The unintended consequences of success of a startup are not always what the creator envisioned for the company’s future. So it was when Detroiter Henry B. Joy became involved with Packard. Joy saw two Packards in 1902 and was struck with them. He bought the only one for sale in Detroit, a Model C. Joy liked his car enough that he convinced nine other Detroiters to invest $250,000 in the company. The influx of cash would allow Packard to expand and increase production, but the city officials in Warren, Ohio, apparently lacked vision and refused to let the company expand. The solution was to move the company to Detroit, where the city fathers were much more interested in the expansion of the automobile industry. James Ward Packard agreed to the move of the company, but he was not personally interested in moving from Warren. He and his brother had their very successful electrical equipment business to run, and possibly more importantly, he had fallen love with a woman who didn’t want to leave Warren.

Packard would remain President of the company bearing his name until 1909 and Chairman of the Board until 1912, but he was not happy with how the company bearing his name was being run. Joy and his investors were an annoyance to Packard with their pressures about styling and engineering modifications. The last straw came when one of the investors, unhappy with his car, sent an abusive letter to Packard about the problems he was having. That caused Packard to withdraw from the daily operation of the company, allowing Joy to become President in 1909.

Despite the management turmoil, the company continued to produce better and better automobiles. In 1903, a Packard dubbed “Old Pacific” was the second automobile to cross the United States. The trip took 61 days to travel from San Francisco to New York, but any successful transit of the continent was newsworthy. “Old Pacific” was a Model F Packard and, in one sense, the end of the early Packard era. Until then, Packard focused on single-cylinder engines; Joy was interested in multi-cylinder autos. The first 2-cylinder Packard was the Model F, and it was followed by the Model K with a 4-cylinder engine. An even more modern car followed in the Model L. It was a 4-cylinder with a number of engineering and styling changes that made the new model more like the cars coming from Europe. Its styling added two details that became associated with Packard for many years – the yoke-shaped radiator and the hexagonal hubcaps. The Model L also set performance records. In 1904, one was driven for 1,000 miles on the Grosse Pointe track in under 30 hours, averaging 33.5 mph to establish a new distance record.

Packard was not a company to ignore a news story that suggested that their cars were fast and reliable. They had a great opportunity to do that after events that included one of their early 6-cylinder cars. Harry K. Thaw, heir to the family coal and railroad fortune, murdered architect Stanford White because he had once sexually assaulted Thaw’s wife when she was 16. Found not guilty by reason of insanity, Thaw was sent to an asylum for the criminally insane. In 1913, Thaw escaped the asylum in a Packard Six, supposedly hitting speeds of 80 mph on a run to Connecticut where he could not be extradited. The Packard magazine reproduced newspaper articles about the escape and added: “When high speed is necessary, when a fast getaway is absolutely necessary, ask a man who owns one.”

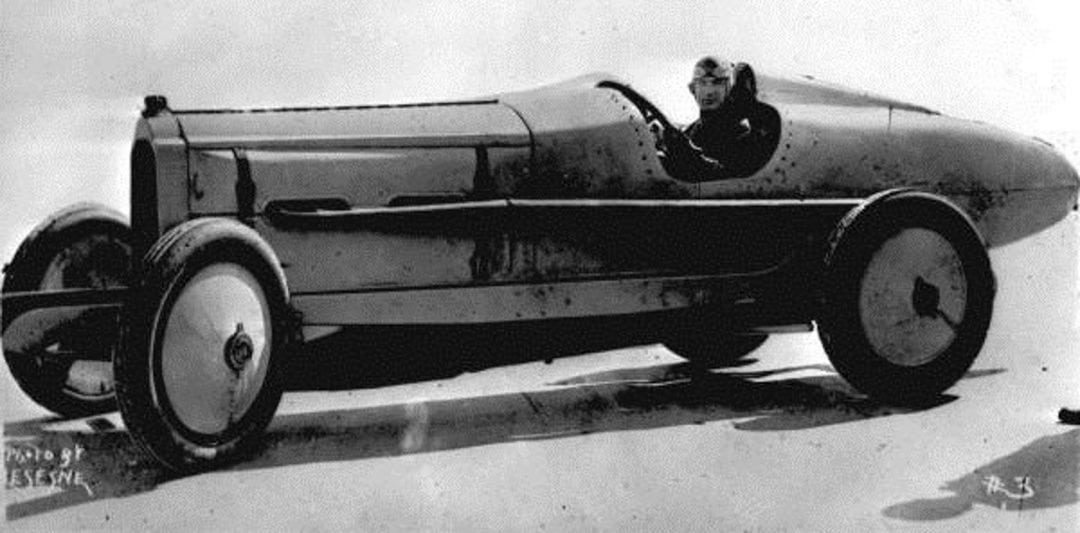

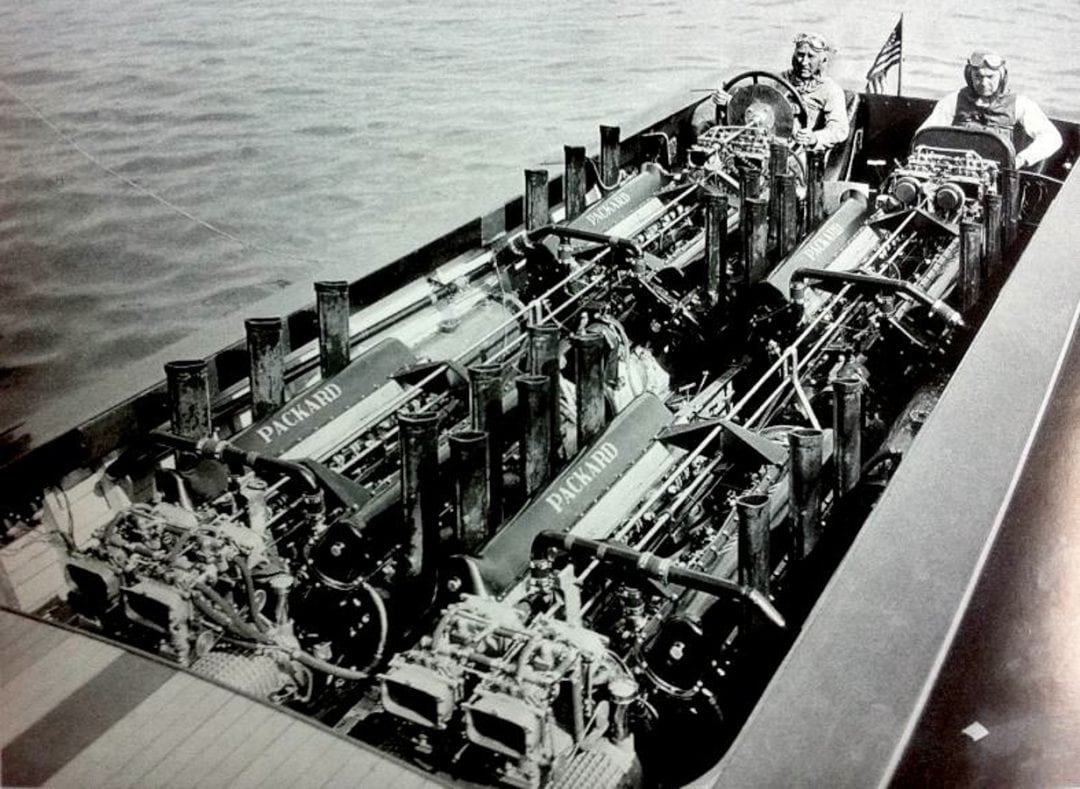

The second decade of the 20th century was a good one for Packard in several ways. Publicity was good – Melvin A. Hall drove a Packard around the world, starting in 1911 and finishing 18 months later. Jesse Vincent joined Packard in 1915 and designed the first U.S.-produced 12-cylinder automobile, the Packard Twin Six. The engine was an L-Head with a displacement of 424-cu.in. It used aluminum pistons and produced 85 hp at 3000 rpm. That engine was modified twice with exceptional results. For use in WWI, the engine became the Liberty Motor used successfully in many aircraft during the war. The U.S. government awarded commissions to civilians involved in developing aircraft engines, and Vincent was awarded a commission as a Lieutenant Colonel. From that time forward, he was often referred to as Colonel Vincent. Ralph de Palma used one of those engines to set a land speed record of 149.875 mph on land, and a marine version took Gar Wood to a record of 124.91 mph on water. That marine version of the engine would win 10 of 13 Gold Cup races.

Alvan Macauley and the Halcyon Years

One potentially traumatic change, in 1916, led to the best years for Packard. In 1916, Joy was approached by Charles Nash and James Storrow about purchasing Packard. Annoyed by his co-owners refusal to accept the offer, Joy left as President. He was replaced by Alvan Macauley, who had joined Packard as General Manager, in 1910. Macauley was a major influence at Packard and led the company during its best years. He remained President from 1916 until 1942 and retired as Chairman in 1948. Many of Packard’s finest automobiles were designed and produced during his time at the head of the company.

As successful as the Twin Six had been, it was replaced in 1923 by an equally powerful and more efficient straight-8 engine. By then, Packard was concentrating on its 6- and 8-cylinder engines, and it marketed the best straight-8 in the world. The engine was an L-Head with a nine bearing crank, and a displacement of 357.8-cu.in. It produced the same 85 hp at 3000 rpm as the Twin Six.

Willian Doud Packard died in 1923, followed by his brother, James Ward Packard in 1928. No Packard had been involved with the company for quite a few years, but the company was proud of its early years. In honor of the Packards, their family crest was added to the radiator shell and remained a symbol of the company’s cars until the demise of the company.

The quality of the automobiles produced by Packard was recognized by people around the world. At home, Packard was second only to General Motors with the number of stockholders. Owners of Packard automobiles included FDR, who had an armored one, Walter Reuther (Pesident of the UAW), General Chiang Kai-Shek and Al Capone. Reuther’s rationale for owning a Packard may have come from the company being the first to accept the UAW because the company’s leaders believed that treating their workers well insured attention to quality. Packards even made inroads in Russia. Czar Nicholas had a Twin Six with skis instead of front wheels for use in snow. His brother, Grand Duke Michael, tried to escape the revolution in his Packard, but was sadly unsuccessful. That car was subsequently used to win a road race from Leningrad to Moscow. Partly as a result of that performance, Russia imported many Packards for Stalin’s use. Eventually, they copied the Packard and called it the Zis.

One amusing story about a Packard during this era was reported by Automobile Quarterly, Volume 1, Number 3. In that article, titled “Packard – A Great Name Passes On,” Mohoney reported that: “In the absence of the Tokyo dealer, mechanics went joy riding in the first Twin Six to arrive in Japan. The machine landed in the moat of the Imperial Palace and the mechanics were fined for ‘disturbing the royal goldfish.’” Packards were truly revered by the wealthy and royalty worldwide.

The last year Packard offered only high priced cars was 1934 when it added the 120. The decision to produce the less expensive Packard 120 with its 6-cylinder engine drew some criticism, but it was a very nice automobile, and it probably saved the company during the economic downturns of the time. Packard stock had fallen from 129 points in 1929 to 2 points in 1933. It was obvious that a less expensive car was needed. The 120, named for its 120-inch wheelbase, sold so well that, in 1936, it moved Packard from 12thto 10thamong automakers, passing Chrysler and Nash. The 120 was built in several body styles and had a top price of $1095, which put it among the upper limit of medium-priced cars. Even though it was less expensive, Packard insured that the car was well engineered. It was the first Packard with the Saf-T-Flex front suspension, which was ultimately adopted for all Packards and, after WWII, by Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Daimler and Lagonda. Packard was still doing things right, even though it was no longer concentrating on luxury automobiles.

The sales success of the 120, and slow sales of the bigger cars, prompted Packard to produce an even lower priced 6-cylinder car, the Packard 6. By 1939, the 12-cylinder cars were gone from the line-up, and there was increased emphasis on the 120 and 6. The old, large Super 8 was replaced by a new Super 8 that used the 120 body and chassis. There were still some very special Packards being built – by Dutch Darrin. With full custom coachwork nearly dead, Darrin produced semi-customs built on stock Packards. It is estimated that he built as many as 150 of these semi-custom Packards from 1938 to 1942.

As the conflict in Europe was developing into what would become World War II, Packard had its second best pre-war sales year in 1940, selling 98,000 cars. There were a number of developments, although several of them were simply name changes. The 6 became the 110, and the Super-8 was now a 160, and there was a plusher version called the 180. The 120 was continued. Packard was the first automaker to offer air conditioning, including it on their closed 8-cylinder cars. The system was cumbersome and somewhat unhandy. The evaporator was quite big, so it was mounted in the trunk. The compressor ran all the time, so the faster you went, the cooler you got. In order to turn off the air conditioning, the drive belt had to be removed.

The man responsible for the 120 was George T. Christopher. He came out of retirement in 1934 to become Packard’s Vice President of Manufacturing. In that role, he oversaw the development of the car that saved Packard during the Depression. When Macauley became Chairman of the Board, Christopher became President and served from 1942 to 1949. Christopher would eventually be replaced by Hugh J. Ferry as President in 1949.

Ferry was hired as a payroll clerk at Packard in 1910. His advancement through the company was steady. It was under his guidance that the work on the marine and aviation engines reached their pinnacle. Using Colonel Vincent’s design, Packard produced the 12-cylinder engines used in PT boats during WWII. It was the aircraft engines, though, that were the company’s most important contribution to the war effort. Packard undertook the redesign of the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine. The result was a liquid-cooled, supercharged V12 engine that was an important part of the air war. Packard produced 55,523 of the engines, more than all five British factories together.

The Decline and Fall of Packard

Packard and Christopher faced some significant challenges after WWII. Steel was scarce, and the design of the cars was outdated. Demand was high, so dealers wanted cars. A decision made in 1940 exacerbated the automaker’s problems. Macauley had given all Packard’s body building to Briggs Body Company in 1940. Then Briggs increased its prices to more than it cost Packard to build the bodies in their own plants. Based on the dealer’s calls for more product, Christopher predicted that Packard would produce 200,000 cars. Dealers expanded in anticipation of new cars, but the reality was that only half that number of cars were built. In 1947, with that year’s model cars on the dealer lots, Christopher announced a new model, which was devastating for sales of the ’47 models. Between 1947 and 1949, Packard lost 500 dealers.

Another problem facing the company was that the company’s older leaders were retiring, but no one had been groomed to replace them. Christopher left in 1949 and was temporarily replaced as President by Ferry, who became Chairman and was replaced by James Nance in 1952. Packard continued to innovate – the Ultramatic transmission is one example of their innovation. There were some new designs with Packard’s “Contour Styling,” but although the designs had positive points, there was nothing special about the cars. The company still seemed viable, but a series of decisions by Nance and some unfortunate ones by others took Packard out of the marketplace.

Nance had little regard for the company’s past. In Mahoney’s Automobile Quarterly article, he reported Nance’s position: “The old was derided, the past was of no consequence, and to emphasize his philosophy he ordered the destruction of the Packard historical files and records.” Thankfully, there were devoted employees who saved what documents they could. Packard had been buying parts from other manufacturers, and the others reciprocated by buying parts from Packard. American Motors, for example, bought engines from Packard. Nance decided to stop the agreements, so American Motors and others stopped buying engines and parts from Packard, killing the agreement with American Motors and resulting in a new engine assembly line having to be scrapped because of less demand. Then Chrysler purchased Briggs Body Company in late 1953—1954 saw the last of Briggs bodies built for Packard.

Nance wanted to acquire Studebaker then merge with Hudson and Nash in order to compete with the Big 3. Nance got Studebaker and created the Studebaker-Packard Corporation in 1954, but Studebaker was not a healthy company, a fact overlooked during the purchase. Nance’s goal to merge with Nash and Hudson was scuttled when George Romney became President of Nash and decided against the merger.

The new company, now on its own with no opportunity to reach the Big 3, had to address the manufacturing challenges it now faced. The solution was to buy the old Briggs facility as its new manufacturing facility. The costs of moving the assembly lines were higher than anticipated. Resulting production problems and the reduced quality of the Packard automobiles took the company into a downward spiral. Problems with credit followed, a faulty axle flange caused nearly half of the 1956 production to have to be repaired, and sales dropped to 1,745 cars in 1958. By then, the cars were called Packardbakers, and their design was not attractive. The Packard name was dropped in July 1958, although the company name wasn’t officially changed to simply Studebaker until 1962.

In 1949, 11,000 people worked for Packard. When the plant closed, there were only 4,000 left. Many of those 4,000 were long-time employees; 20% had been with the company since 1925. Competence of the workers wasn’t the problem, so what did cause Packard’s demise? Mahoney suggests that there were three reasons:

- There were plenty of small cars available to the public. Roads had improved, so big cars were no longer needed for a comfortable ride.

- The demise of luxury cars left Packard with no fall back. It’s smaller cars were not profitable enough to sustain the company

- Personalities prevented the merger that might have made Packard a successful high-end marque for Nash.

Ninth Series Packards

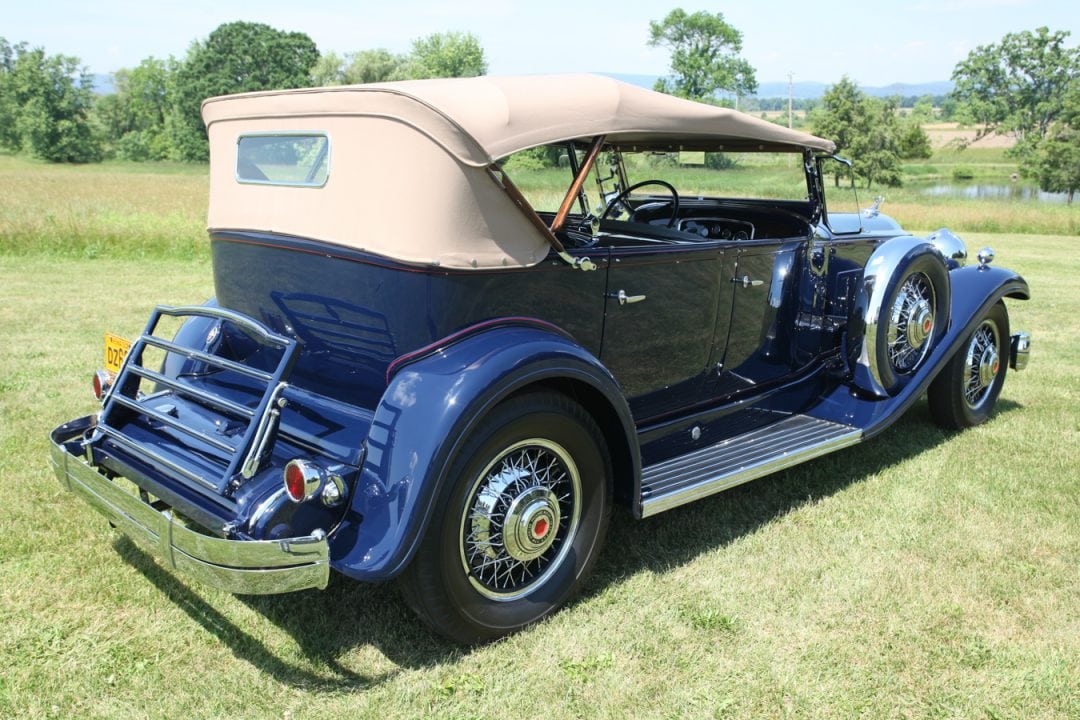

How Packard automobiles were labeled seems to have depended on who was running the company at the time. Early on, the series were identified by letters in the alphabet, although not always in alphabetical order. Alvan Macauley believed in using series numbers, so upon his arrival as President, he instituted a numerical system of series. References are a little vague, but it appears that he backdated Series 1 to 1912. The subject of this profile, a 1932 903 Sport Phaeton, is part of the ninth series of Packards. The series was announced to dealers in June 1931 and was visually different than previous Packards because of its mildly V-shaped grille and the addition of harmonic stabilizers at the ends of its bumpers to dampen chassis harmonics. The V-shaped grille is probably the grille most associated with Packard.

The Ninth Series included seven models. At the “low” end was the Light Eight (900). It was an attempt by Packard to counter the effects of the Depression. It was a very nice car and was definitely a Packard. The result was that build costs were high enough that the sales price wasn’t significantly lower than other Packard models. The Light Eight didn’t attract new buyers to Packard, as had been hoped, and the model lasted less than a year.

The Standard Eight was available as two models, 901 and 902, both with the same L-Head Straight-8 engine. Neither was available with custom bodywork. The 901 had a wheelbase of 129.5 inches and was available only as a five-passenger sedan. A total of 12 body styles were available for the 902, which had a longer 136.5-inch wheelbase. A number of innovations were available on these models, including ride control. The harmonic stabilizer front bumper was an option. Initially, the cars had a four-speed transmission, but that was changed to a synchromesh three-speed with a vacuum clutch late in the model run.

Next up the line were the Deluxe Eight (903 and 904) and Individual Custom Eight (904), using the same engine. The most noticeable technical difference between these models was the wheelbase – the 903 had a wheelbase of 142.5-inches, and the 904 wheelbase was five inches longer. The Deluxe Eight 904 was available as either a five/seven-passenger sedan or as a sedan-limousine. If a buyer wanted more body style options in a straight-8 powered Packard, there were a total of 15 bodies offered for the Individual Custom Eight – five by Dietrich and 10 “Custom Made by Packard” styles. More will be said about the Deluxe Eight 903 model below.

Packards could still be had with a V12 engine in 1932, and the last two of the seven models in the Ninth Series were Twin Sixes (905 and 906). The 905 and 906 used the same chassis as the 903 and 904, respectively. Appointments in the Twin Sixes were lavish, even compared to other Packards. The 905 was available in 10 body styles; the 906 had 11 choices available.

1932 Packard 903 Sport Phaeton SN: 53114

Frank Buck is both an interesting man and a man with a lot of interests. He is also an example of what hard work and an entrepreneurial attitude can produce. He worked hard in his youth at a service station and a Chevrolet dealership before he became the owner of his own service station when he was 23. He added road service, and his business took off. A second station, an Esso near I-80, became available, and business boomed. His was possibly the busiest road service and towing company in that part of Pennsylvania. He did 24-hour road repairs, added fleet service, became a Mack service dealer in 1972, and received a Peterbilt dealership in 1977. His businesses were going “gang busters!”

Success in business allowed Buck to delve into his interests. Arriving at his Civil War era farm, the first thing noticed is the beautiful stone farmhouse that predates that conflict. Then the eye is drawn to the steel building on the hill beyond the house. That’s where Buck keeps his collections. His collections take your breath away – literally, your mouth drops open, and you stop breathing. Packards, Corvette racecars, Model A Fords, and World War II memorabilia. And what memorabilia – uniforms, an entire rack; a shelf of helmets worn by the Band of Brothers, members of E Company, 2ndBattalion, 506thParachute Infantry Regiment, 101stAirborne Division made famous in the book by Stephen E. Ambrose; jeeps, 18 were counted; and then there was the heavy equipment, including a variety of trucks, a running Sherman tank, tank retriever, and the prime mover used to haul them.

Each of his interests has a reason. WWII – Buck says, “I’m a product of WWII, being born in 1942. All of my friends of that era had relatives in WWII and Korea.” Unlike many born of that era, Buck’s interest remained. Model As – “I had Model A Fords when I was a kid in high school.” He and his brother bought one in 1958 for $120. The previous owner was a kid going off to college. He used pillows covered in red plastic for seats. “After a while, when you’d hit a bump, the feathers would fly.” Corvettes – Buck had a 1957 fuel-injected Corvette when he was 18. It was a former racecar, and it was the fastest Corvette in his county. When asked about speeding tickets, Buck said, “Um, we had a lot of fun with it.” He now has several Fuelie Corvette racecars, and he and his son, Adam, regularly run them at The Grand Ascent, a hillclimb on a service road at the Hotel Hershey that is part of the annual Elegance at Hershey weekend.

As for Packards, Buck bought his first Packard in 1971 for $1500. A 1930 Standard Eight Model 733 four-door sedan. “It was an original car, and the person who had it started to do work on it and lost interest. I had to scrounge to get [$1500] in 1971. That was the first I could afford a Packard.”

Buck is detail oriented. It shows in the quality of the work on his vehicles and in the records he keeps. He produced a notebook listing the cars he’s owned. “I’ve owned about 400 vehicles since I was a kid, and I have them all listed. I have [close to] 30 Packards [in] here. His next Packard was a 1937 Sport Phaeton that came completely disassembled. He managed to buy cars low and sell high, usually after rebuilding or improving the cars.

In Buck’s garage, there are three Packards, each with a story. The 1936 Phaeton is the last year of that body style—after ’36, Packards had wind-up windows. The family of the original owner had the car until 1972. Their son drove it in Chicago back and forth to the airport until they sold it. Buck bought it from a friend. He knew the car, so he bought it over the phone and drove it home from Nebraska. “It is probably the finest unrestored ’36 Packard in the world.”

Buck had seen and fallen in love with the 1934 Packard that now sits in his garage. It finally came available in 1978 because the owner was buying another Packard. The price was set, so Buck sold a few cars to buy the Packard, and flew to pick up the car. The owner would only accept cash, so “I flew out with $85,000 in cash in my jeans. You could do that in those days.” Since 1978, he sold the car and bought it back. He’s also driven the car to British Columbia. Can you say reliable?

The 1932 is the fourth 903 Sport Phaeton built by Packard. It is his favorite Packard. It was the last year of the open fenders and the first year of the V-grille. And he prefers the straight-8 over the 12-cylinder cars. He sold this car and bought it back 25 years later and started the restoration. His restorations are winners. Buck said, “The smartest thing I ever did was get involved in judging for AACA (Antique Automobile Club of America) and CCCA (Classic Car Club of America). I learned [what was right] through the judging.” Knowing what is right really helps in making a restoration the best it can be. An example of knowing what is right can be doing simple things correctly. The bows for the top, for example, “they’re boney. Otherwise you can’t fold the top. You see cars with a lot of padding in here, so you don’t see the ribs. If you fold the top down, you can’t get the boot on.” Details like that helped Buck receive a Junior Award from AACA the first time he showed the car. He has taken the car to five CCCA Grand Classic shows and received 100 points at four of them.

Buck summarized the restoration process for this car, saying the paint was stripped using a stripper not a blaster. The frame was blasted. His Peterbilt dealership had a state-of-the-art body shop, so all painting was done there. The engine was rebuilt in Connecticut, and the upholstery and top were done in Pennsylvania, with Buck involved. All the assembly was done in Buck’s own shop at his home. The ’32 has been to Pebble Beach and twice at Amelia Island. It took a second at Amelia and won the Robert Turnquist Award for the Most Elegant Packard. At Pebble, it was third behind two Packards done by professional restorers, including a Twin Six once owned by Clark Gable. “I didn’t consider us to be professional restorers, but we got third going up against some of the best restorers in the country.”

Driving Impressions

Automobile manufacturers of this era were challenged to make their cars comfortable to drive over the slowly improving roads of the United States. Packard was one manufacturer who worked hard to make their cars acceptable to the people who could afford to drive them. The 1932 Sport Phaeton had several improvements that helped Packard retain is standing as one of the most livable cars of the time. The harmonic stabilizer has already been mentioned. This model also had a ride control unit that allowed the selection of three shock absorber settings for different road conditions. Engine mounting to the lengthened and reinforced chassis was by rubber engine mounts. The driveshaft was jointed and rubber mounted. A redesigned air cleaner was quieter and had less vibration. All this, together with Packard’s exceptional quality, made the car SMOOOOOTH!

I first rode with Adam, who acquainted me with the controls and the starting procedure, then it was my turn. The first impression is that this car is big. Still, it was important for a driver to be a bit flexible, since the large steering wheel made entry to the driver’s seat tight. Once seated, it is a very comfortable car. It is pure luxury, with plush seats, a glorious wood dash, and wood highlights on the doors.

The starting procedure, had the engine been cold, would have been to pull out the choke and pump the accelerator a few times, turn the ignition switch on, and, with the car in neutral, push on the accelerator and starter button. The car was already warm, so it started immediately without the choke. The clutch is smooth and easy to engage. Shifts of the synchromesh three-speed transmission were smooth and without any snicks. The straight-8 engine is so quiet, it is hard to determine that it’s running at idle. The exhaust noise has only a bit of presence when driving the car, certainly nothing to annoy the passenger ensconced behind their separate windscreen, a multi-part screen that can be folded to completely protect them from the wind and road dust. One thing to remember is that the car has mechanical brakes, so the driver has to anticipate stops. Still, at 30 to 40 mph, stops were reasonable both in the pressure required on the pedal and the distance it took to haul this large car from speed. I have to suspect that emergency stopping from higher speeds would be stressful for the driver.

We used the long, tree-lined drive at the Buck farm for our driving impressions. The driveway was very smooth, so it wasn’t a test of the car’s ability to smooth out an irregular surface, but we got several opportunities to experience what it takes to turn the car around. The transmission was a joy; it was easy to find reverse, and the gear engaged smoothly. The real purpose of the huge steering wheel was realized when turning the car around. A large diameter wheel does a lot to reduce the effort of turning the car at low speeds. Steering while driving forward at cruising speed was a pleasure – quick and light.

The Bucks take this car on a lot of tours, and I can see why. It is a pleasure to drive, and Packard reliability removes some of the anxiety associated with driving a car over 80 years old any distance. I’d love to join them on one of their tours, and I’d especially love to drive this car on the much-improved roads of the 21stcentury.

Specifications

Body 4/5 passenger Phaeton

Chassis Steel double drop design with cross bracing

Engine Front mounted, L-Head, Straight Eight

Displacement 384.8 cid/6.3 liters

Bore/Stroke 3.5 inches(88.9mm)/5.0 inches(127mm)

Horsepower 135 Hp/101 KW @3200 rpm

Compression Ratio 6.0:1

Induction Detroit Lubricator Updraft Carburetor

Transmission Synchromesh, three-speeds forward, one reverse

Clutch Vacuum clutch

Differential Hypoid

Wheelbase 142 ½ inches/3610mm

Front Track 57 ½ inches/1461mm

Rear Track 59 inches/1499mm

Length 211.4 inches/5369mm

Width 71.9 inches/1826mm

Height 68.7 inches/1745mm

Weight 4795 lbs/2179.5Kg

Brakes Mechanical drum brakes

Wheels 19 inch wire

Tires 19×7.00 inches