In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Canadian industries of aerospace and racecar design were at the forefront of a new wave of industrial design. Avro Aviation engineer James C. Floyd had come up with the CF 105 Avro Arrow, a 1500-mph delta-winged fighter aircraft, and Bill Sadler had created a series of sports racing cars that were distinguished by advanced design on a budget that would not have covered Enzo Ferrari’s office supplies. All of a sudden, however, it all came to an end. The Avro Arrow’s cancellation in February of 1959, and Sadler’s departure from racing in the fall of 1961 meant that much more than jobs were lost. A potential Canadian aerospace industry went south—literally—as many Avro engineers joined NASA for the moon missions, and Sadler went south too, to Tri-State College and an engineering degree with such high marks that they earned him a full scholarship to MIT in electrical engineering. From there, Bill went to Area 51, working for General Dynamics on tasks he still cannot discuss even today. This interview by John Wright, however, is the result of conversations over many years, and will target Sadler’s racecars and his own career in racing.

VR: Can you begin by telling us about your early engineering exploits?

Bill Sadler: I grew up in an automotive environment, which I inhaled as naturally as the air around me. My parents ran Sadler Auto Electric, in the small Ontario city of St. Catharine’s. I grew up in the shop and when I was old enough, I was put to work at various odd jobs.

Sadler: I wanted to build a car to my own specifications, but I had no car. In the 1940s there were not many teenagers who could afford a car. However, my Dad was getting ready to discard a 1939 Austin Bantam panel truck. He gave it to me and I immediately tore it down and repaired it. I took the top off and made my own convertible top, which I sewed with my mother’s old Singer treadle sewing machine. Then I converted the floor shift to a column shift—which was fashionable for the time. The structural integrity of the vehicle was compromised because I had removed the top, but I drove that converted truck everywhere, even to New York.

VR: After working for your parents a while, didn’t you accumulate enough money to purchase a new car?

Sadler: I purchased a brand-new 1949 Hillman Minx convertible. I was paying $80 a month for that car, but I was making considerably more in the shop.

VR: No doubt you couldn’t wait to squeeze more performance out of that car.

Sadler: Right. We had driven the car to Mexico, and that trip gave me the opportunity to think about my future. I decided to leave school and devote myself full time to work. My father had a branch shop in Hamilton, and it was not doing well. I asked him to let me manage it, and I brought it up.

VR: You also had some time to think about how you wanted to boost the performance of the Hillman. Can you tell us how you went about it?

Sadler: I put a Ford V8 60 engine in the car, with two Stromberg 97 carbs and a hot cam. I could buzz it to 9,000 rpm, and it put out around 150 horsepower.

VR: Then you entered the Hillman in the 1953 Watkins Glen races, how did that go?

Sadler: The 1953 race was held on the new 4.6-mile course on top of the hill outside Watkins Glen. There was a long one-mile downhill straight, which led into a very tight right-hand corner. The Hillman was very fast there, but the problem was the tiny front drum brakes, so small you could hold the front brake drums in your hand. After several laps while leading many two- and three-liter cars, I felt a strange thump on the brake pedal while braking for the sharp right turn. I guessed that the brake linings were gone. I drove for a few laps using the hand brake and the rear brakes only. Eventually I was black-flagged for going too slow. Also, I had to drive home in the car, doing this with the hand brake.

VR: Was that when you came to the obvious conclusion that it was time to build a proper racecar?

Sadler: I wanted to design my own car with the most advanced technology I could find at a price I could afford. I was able to pick up a second-hand Jowett Javelin in Toronto, a car that seemed to have the advanced features I wanted.

VR: But that was just a start.

Sadler: I drew chalk lines on the floor of the garage in Hamilton and specified a double two-inch tube frame. I hired a welder to do the work, but I taught myself to weld and let him go. I took the torsion bars from the Jowett and made them longitudinal in the front and transverse in the rear, and individually adjustable. I took a Morris Minor rack and pinion steering system and adapted it to the front end. I put a rudimentary sheet steel body on it along with cycle fenders welded onto steel rod.

VR: Was it then time to test it with a return to The Glen?

Sadler: My first race with the car was at The Glen in 1954. The car had a very harsh ride, the expansion strips on the throughway were killers. We had to change drivers to give the rear end a rest! Those were the days when we went through tech inspection at Lester Smalley’s Garage. It seemed like an insurmountable hurdle, but the car passed. There was one problem. The car ran well until it got to 4,000 to 5,000 rpm and then it would misfire. I couldn’t figure it out.

VR: How did you solve that problem?

Sadler: One night, I connected up some headlights to the ignition switch. I started the car and the headlights flickered just at the same time the engine had that elusive misfire at 4,000-5,000 rpm. I discovered that I had a resonating dashboard switch. At 10Hz the darn thing would resonate and affect the ignition. I put a different toggle switch in the dash and the engine misfire went away.

VR: Your first season racing your car had some indifferent results. Over the course of the ensuing winter didn’t you came up with some ideas of how you could improve the Sadler Special?

Sadler: That winter a friend had an accident in his TR-2, and I went to the hospital to visit him. He told me the car had been totalled. I asked him if I could buy the car for the engine. He agreed. Now I had a more powerful engine for my special.

VR: Didn’t you encounter a problem fitting the engine in the chassis?

Sadler: The stock TR engine with the SU carburetors interfered with the main chassis tube. As a result, I designed my own fuel injection system for the engine. I took a piece of four-inch aluminum pipe and cut it to fit. I aluminum-brazed it, and I installed a four-inch butterfly throttle and constructed linkage to control it. For a fuel pump, I took a standard fuel pump and replaced the normal pressure-limiting spring with a much heavier spring. Thus, the displacement of the fuel was now constant per revolution of the engine.

I also had to calibrate the system with a feedback valve to vary the flow of gas with the speed of the engine. I had the testing machinery in the garage to ensure the system worked before I took the car on the track.

VR: Didn’t you also construct a new body for the car?

Sadler: Over the winter of 1954-’55 I built a new fiberglass, envelope-style body for the car. I got war surplus ¼-inch steel tubing, bent it on chalk lines I had drawn on the floor of the garage and tack-welded it to the tubular frame. It was very symmetrical. I had a complete outline, including a grille. I got some expanded metal lath and tack-welded it and plastered it to get a male mould. I put fiberglass on top and finished off the outside with a grinder. Now, I had a male buck with a fiberglass body on top. I broke up the plaster and I had a body.

VR: How did the car run with, now, around 100 horsepower from its injected Triumph engine?

Sadler: I ran the car at The Glen with indifferent results, but then Chevrolet came out with their new 265-cubic-inch V8 engine. I had raced the car at The Glen, Edenvale and Harewood Acres, and although it was pretty fast, there were oiling problems on the corners with the lower end of the engine, resulting in a burned bearing. Then I thought, I’m gonna put a Chev V8 in this car.

VR: That took place in the fall of 1955, did it not?

Sadler: I installed the engine and hooked it up to the Triumph transmission and the original Jowett rear end. As I remember it, the car was pretty light, weighing in at around 1,200 to 1,300 pounds. My parents were the distributors of Rochester carburetors, and I managed to get a two-four-barrel manifold for the engine. However, it scared the living hell out of me when I drove it as it wouldn’t handle. I thought to myself, there’s got to be a better way of doing this.

VR: So, what did you do to address the handling problem? Paul van Valkenburgh said that you created a homebuilt transmission differential at the rear of your car, combined with an independent rear suspension.

Sadler: I re-planned the car. I traded the TR-2 engine to Bob Hanna and Jack Wheeler of Autosport for a 1932 Alvis pre-selector gearbox. I took the Alvis gearbox and got a 1940 Ford rear end and coupled them together for a modified rear end. Thus, I had a transaxle and a pre-selector gearbox differential.

VR: Then you built a new frame to handle the power…

Sadler: The Mark II frame was built from 3- and 3½-inch chrome moly tubing from a firm that dealt in war surplus material. The Chev V8 sat far back in the frame to get as much weight as possible on the back wheels. I chose a low-pivot swing-axle arrangement for the rear end.

VR: You put much thought into how you wanted the rear end suspension to work, didn’t you?

Sadler: I analyzed all the available systems because I wanted to keep the tires perpendicular to the track surface. It’s critically important in a high- performance car that you have a very high roll center at the front and a low roll center at the back for optimum cornering and control. The Lister Jags and Ferraris were tail happy, and their solution was to put an anti-roll bar at the front—the wrong solution.

VR: Then you decided to go to England with the new Sadler Mark II.

Sadler: I went to England and worked with John Tojeiro. I participated in some races with some good results, but mainly I destroyed some egos with the car. For example, I entered the Brighton Speed Trial, a one-kilometer drag race. There were some aircraft engine-powered dragsters there. I had the fastest time and then it started to pour.

They waited and waited for the track to dry out and it didn’t and I was declared the winner. The prizes consisted of 100 pounds and two huge trophies. That money paid for the aluminum body I had built for the car with 10 pounds left over. I put the new aluminum body over the car and returned to Canada. However, John Tojeiro kept the trophies! By The way, Moss’s mechanic, Alf Francis was most impressed with the Mark II!

VR: Would you tell us about the 1957 Bahamas Speed Weeks and your part in it?

Sadler: I first heard about the Nassau Speed Weeks in the latter part of my 1957 racing tour in England. I had become friendly with a Brian Naylor who had raced Lotus cars. Brian liked the Mark II and thought it was a great racecar with lots of power. I contacted the organizers and managed to wangle an invitation to the event.

VR: What was your plan?

Sadler: The plan was to have Brian fly into Toronto, I would pick him up and we would drive to Miami to catch the ferry to Nassau. The new aluminum body, all polished up, transformed the Sadler Mark II from a small homebuilt to a professional-looking car. We arrived at Miami and loaded the car. We had to chain the trailer and tow car together so it would still be there after we got back from the race.

VR: Didn’t your Sadler Mark II make quite a splash after its arrival?

Sadler: We were approached by a camera crew and models from Mademoiselle magazine. The photos with me in the car and models draped over the car made it into the magazine’s chic and modern fashion section.

VR: Wasn’t racing scheduled there as well?

Sadler: Brian and I shared the driving duties, which went on over a series of two weeks. Brian came 1st in one of the preliminary races and won a nice trophy. The car did very well in a series of races. And the tow car and trailer were still there after we returned to Miami. In 1958, we won the Queen Catherine Cup in the Mark II at Watkins Glen.

VR: Did the success of the Mark II lead to the refined Mark III?

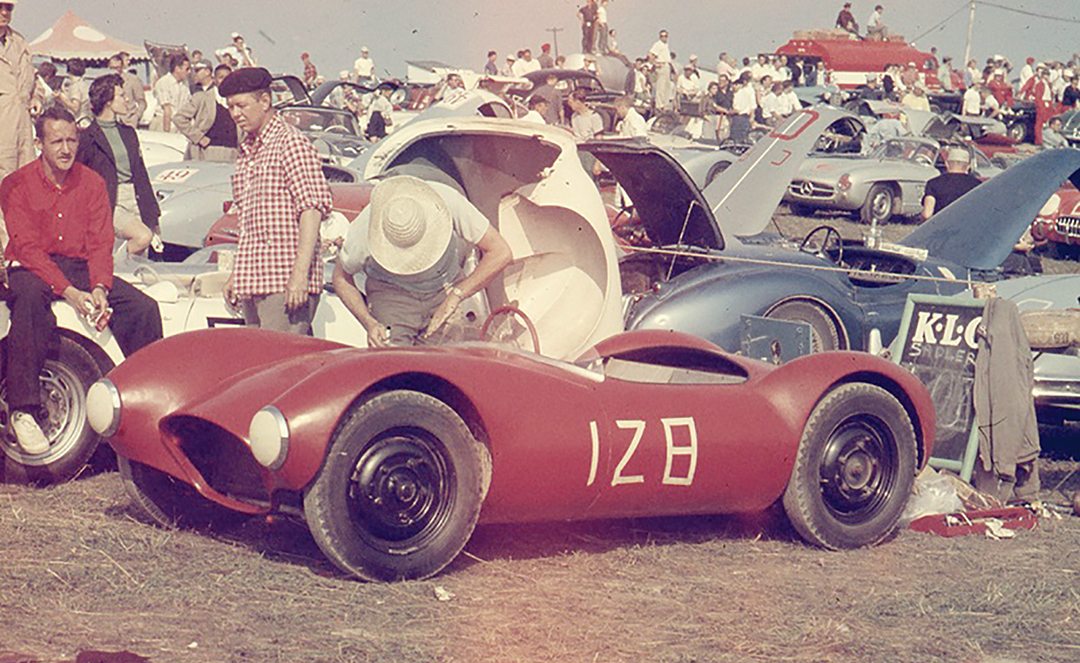

Sadler: The Mark II was a good car, but it suffered from unreliability due to a lack of funds for development. However, Earl Nisonger of Nisonger Corporation, the U.S. distributor of KLG spark plugs, commissioned me to build a Mark III Sadler to be named the Nisonger Special. Bob Said, father of current racer Boris Said, was to be the driver.

VR: Wasn’t there a complication, however, as you told me the car had to be completed by the 1958 Nassau Speed Weeks event?

Sadler: Yes. I had to complete the fabrication of the Mark III’s fuel tank in an abandoned hangar at the Nassau airport circuit.

VR: The Mark III also had an impressive debut, but weren’t there glitches?

Sadler: The Mark III lived up to its promise for a short while. In the early stages of a main Nassau race, the Mark III literally ran away from the international field of racers. However, when he was many car lengths ahead of the pack, Bob Said looked around to see where everybody was. The wind blew his goggles off. He finally got to the pits, got some goggles and took off in a rush. Only he damaged the car when he ran over an airport marker light at the first corner and was forced to retire the car.

VR: Then you constructed the Sadler Mark IV, but built only one car.

Sadler: Dave Greenblatt took delivery of the Mark IV. It was built as the first of a proposed line of customer cars with a solid rear axle instead of an independent rear end. Dave put a Latham supercharged engine in the car. It was later vandalized for its engine. The bits and pieces formed the basis of his Dailu, which eventually was driven by Terry Dale, Don Horner and, in vintage races, by Mike Leicester.

VR: Then you decided to put the engine behind the driver. Can you briefly explain the process that resulted in the Sadler Formula Libre and the Sadler Mark V?

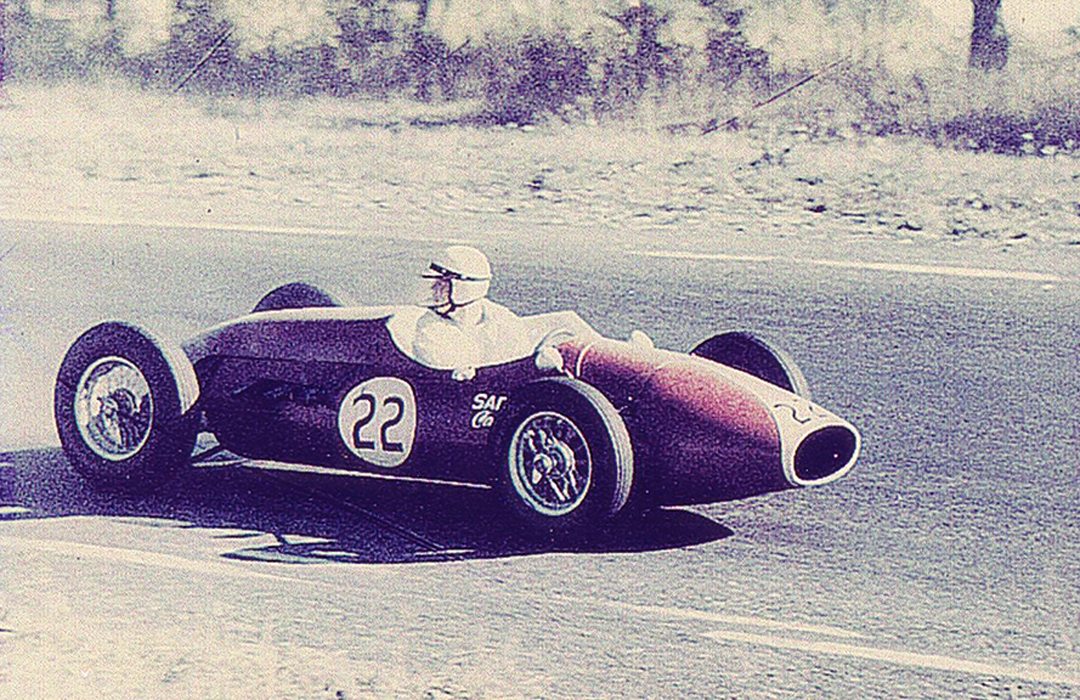

Sadler: I experimented with one of my Sadler Formula Juniors. I installed a Chevrolet V8 where the Austin engine went, but I had no room for a clutch or transmission. When you started the engine, you went. It had so much power it scared me, and I don’t think I ever opened it up. So, I decided to put the engine behind the driver. The car had no transmission, just one gear, with a Halibrand in-and-out rear end. The engine was a 327-cubic-inch V8 with a Duntov camshaft providing a wide power band—with about 300 horsepower. The weight of the car came in at about 1,350 pounds. The suspension was fully adjustable.

VR: Your mid-engined Sadler Special debuted at The Glen about two or three weeks before the GM CERV special made its appearance, in the fall of 1960.

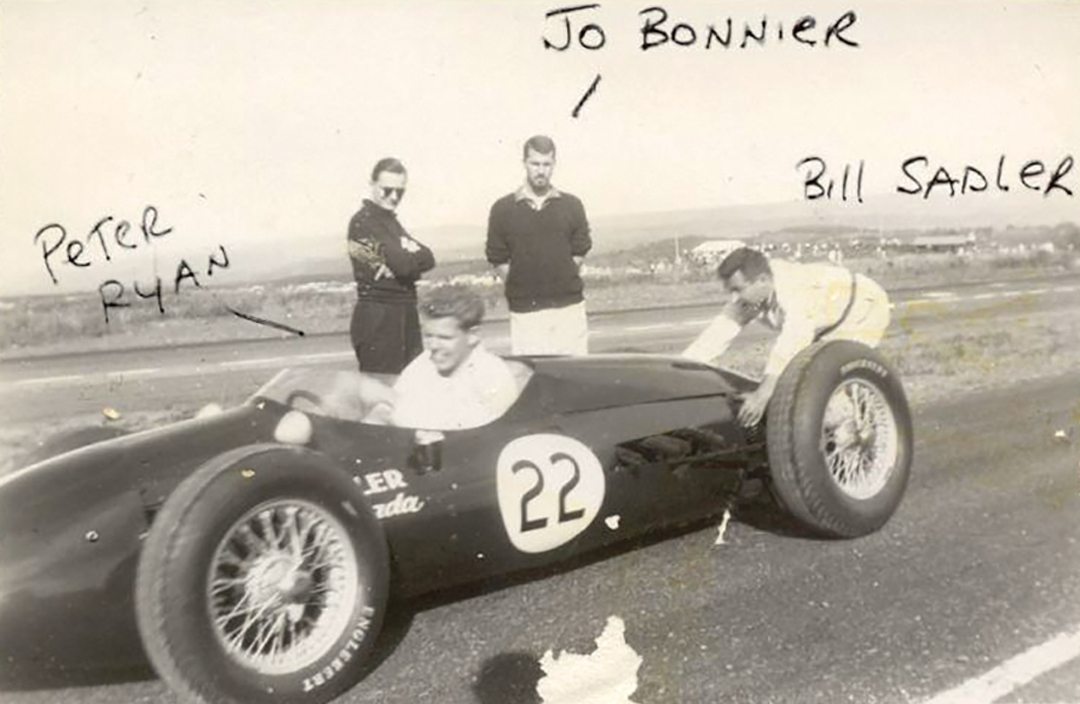

Sadler: We made the race and Peter Ryan was our driver. Peter went off the track and stove in the oil pan. The oil pickup was sucking up air and not oil. He didn’t tell me, and the engine failed. Canadian racer Danny Shaw purchased the car and then it went through a series of owners. Canadian collector and RM principal Jack Boxstrom owns the car now.

VR: Then there was what I might call your chief work, the revolutionary Mark V. Will you tell us about that car?

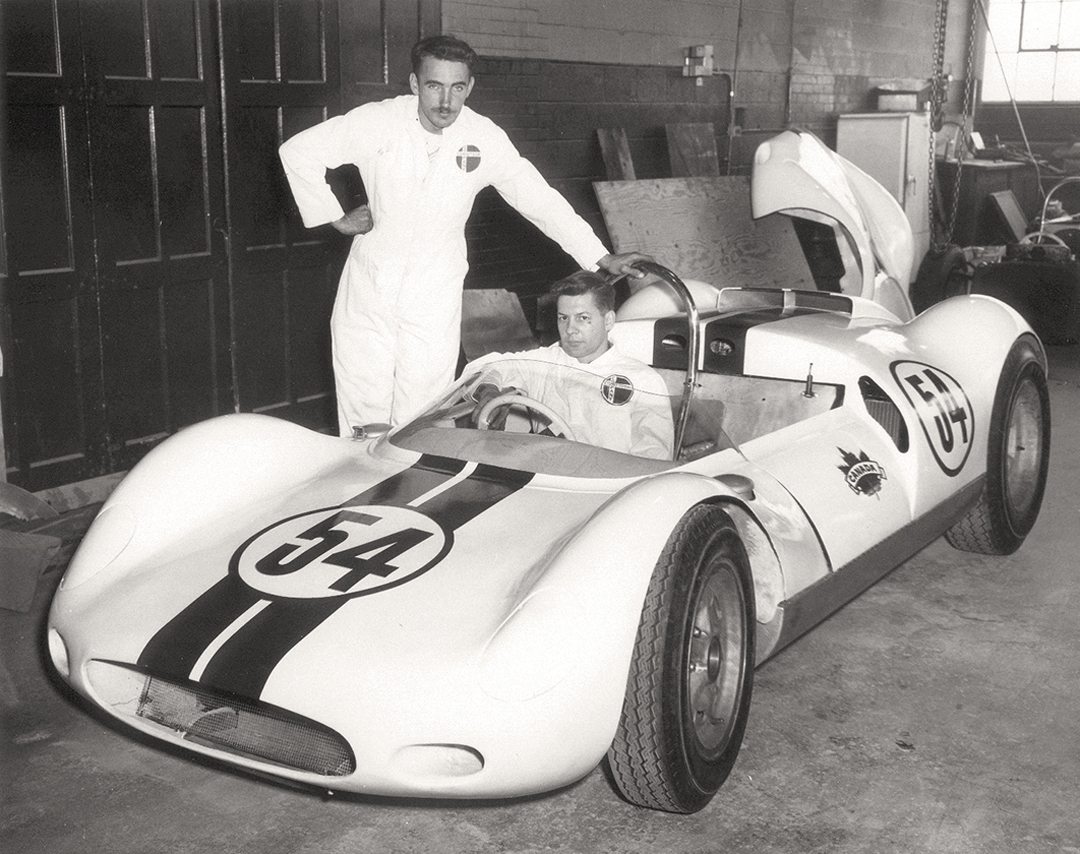

Sadler: Comstock, in the form of proprietor Chuck Rathgeb, approached me to create a world-beating sports racing car. At the 1960 Glen race, Stirling Moss practiced in the Sadler Formula Libre and he told me that the car needed another forward gear and less understeer. I found a sponsor and we started. I decided to design the car to FIA Appendix C rules, and also to the 1954 version of the FIA rulebook that the SCCA used. As a result, the car had a proper windshield and proper doors. The engine in my car was a Chevrolet V8 of 377 cubic inches, while the second car—which Canadian racer Grant Clark would drive—would have a 327-cubic-inch engine.

VR: But wasn’t it in the transmission and differential where you did something different?

Sadler: That’s right. I used the Halibrand quick-change rear end again, but I added an extension, and in the extension were two forward gears and a reverse gear as well. There was one speed for hairpin turns and a top gear.

VR: Then it was time for the car’s debut at the first professional race at Mosport in late June of 1961.

Sadler: We had two Mark Vs there, one for Grant Clark and one for me. We had tested at Harewood Acres and nothing fell off, so we were off to Mosport for the Players 200. Grant finished 3rd and I finished with one gear remaining in the gearbox.

VR: You took a Mark V to the old Meadowvale venue, and Harry Heuer told me that: “Peter went by me so fast, I thought I was nailed to the track.”

Bill Sadler: Peter ended up in 2nd place after his friend, Roger Penske.

VR: Didn’t your involvement in racing end in the fall of 1961 during a race at Mosport?

Sadler: I got into a major disagreement with Chuck Rathgeb of Comstock. Grant Clark stuffed my car into a haybale. I told the crew to take the car apart and repair it. We stayed up all night working on it. Come race day and I was not prepared to race as I felt the car was not safe. It was undriveable. However, Chuck was angry and said I was a chicken-shit. He walked the paddock to find another driver. Danny Shaw got in the car and promptly had an accident at Corner Ten. I was beside myself and decided to walk away from racing because my engineering skills were being questioned.

VR: Didn’t you then go back to school, to a school in the USA?

Sadler: I couldn’t get into a Canadian engineering school as I didn’t have grade 13. As a result, I went to Tri-State College. From there, I received a full scholarship to MIT, and from there to General Dynamics and Area 51…

VR: Well, that’s a story for another day! And today?

Sadler: I live on Vancouver Island, where I am contemplating building another car, or something. This summer, in July, I am going to England for an event called the Silverstone Golden Trophy Races where I will present a trophy to the first front-engined special. I will also drive one of my Sadler Formula Juniors.

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.

I remember well the Sadler Special won the Glen Classic in 1958 and was everybit as fast as the Scarabs and Listers later that year and in 1959. Sadler was not just a genius engineer he was and is a great guy.