In the history of motor-sport safety, few names are as universally recognized as that of Bill Simpson. Initially an active drag racer, Simpson went on to race in various road racing categories before moving on to USAC racing and eventually the Indianapolis 500. While Simpson often demonstrated great speed and competitiveness, his nearly worldwide name recognition would come from the eponymous business he started, manufacturing safety equipment for racers. Starting in the ’60s with drag racing parachutes, Simpson Safety Equipment went on to manufacture the first Nomex racing suits, helmets, fireproof clothing and safety harnesses, used in virtually every form of motor sport around the world.

However, in 2001, Simpson elected to resign from his namesake company as a result of the aftermath of Dale Earnhardt’s tragic death at Daytona. NASCAR officials attempted to lay some of the blame for Earnhardt’s death on allegedly faulty Simpson belts, which Simpson has always vehemently denied. But when he started receiving death threats and even gunshots fired into his home, he chose to walk away from the safety empire that he created. However, Simpson could only stay away for so long before he decided to form a new company, Impact! Racing, which finds him yet again developing safety equipment.

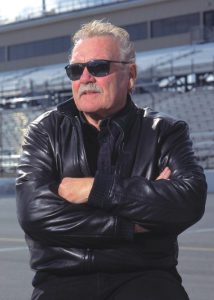

Recently, Editor Casey Annis caught up with Simpson to learn more about his own racing career, the birth of Simpson Safety Equipment and what he sees as the future of racing safety.

I understand you started your racing career through drag racing?

Simpson: That’s correct. I went to my first drag race in 1955.

And so you started as a competitor when?

Simpson: I was first a spectator, and then in 1957, I got hooked up with a guy named John Garen and I went drag racing.

How long did you stay in drag racing?

Simpson: Oh, I don’t know. It was off and on through 1970 actually. You know, I did some road racing in that period. In the early ’60s I went road racing, and then in the mid-’60s, I went over to Europe, and then I did some more road racing later on.

You’re road racing started in the SCCA?

Simpson: Yes, it did.

What category?

Simpson: I don’t think they had Formula Ford, when I started. I ran a thing called Formula Continental.

What year was that?

Simpson: I don’t know, I reckon ’63 maybe or ’64, something like that. We ran all those goofy places like…Oklahoma, someplace out in Virginia. I mean, you know, places that were real dangerous. You know what I mean, no guardrails or nothin’ and shit that you could go over. Castlerock, Colorado. Up in northern California, there’s a place that we raced on a airport circuit and just, you know, those kind of things. And the Formula Continental, I believe, ended up becoming the Formula 5000.

What model cars were you running at the time?

Simpson: Well, I had several. I had a Lotus, I think it was a 48, does that sound right? And then I had a Brabham. I do remember that it was a BT18, because I still have it hanging up in one of my shops. I had Brabhams for a couple of years. They were not real Brabhams; they were built by Frank Williams. They were top Brabham copies.

Were you splitting your time then between drag racing and road racing?

Simpson: Uh, no, because when I went road racing, I didn’t drag race anymore even though I had an interest in some drag cars.

What was it that drove you to road racing having come from a drag racing background?

Simpson: There’s another drag racer, a guy named Paul Sutherland who talked me into going up to Willow Springs to take this Jim Russell School that had just been opened. So, we went up there together, and I got hooked. I thought that was really a thrill. And I went from there, you know?

How did you make the transition to USAC in, what was that, ’68?

Simpson: What happened was, you know, USAC decided they were going to go road racing and so I thought, well, that’s pretty cool, and SCCA and USAC were at war with each other basically and I decided that I was gonna go do some USAC races, so SCCA took my license away from me.

I can’t recall what they were battling over at that time? Was it over who controlled professional road racing?

Simpson: I don’t know. You know SCCA was pissed off because they thought that USAC was coming along and was going to take some of their thunder or something, but if you were an SCCA guy and you drove in one of them deals, they automatically took your driver’s license away from ya. So you couldn’t compete in any more SCCA races. Of course, if they did that today, they’d be hung out to dry.

Anyway, I did that and I ran, I think, eight Indy Car races with a V-8 Chevy that Howard Gilbert had built and I did pretty good. And so, I did it again in ’69, and then USAC stopped doing the road races. And then I tried to go back to SCCA and, of course, I was persona non-grata, so I didn’t get to go back there. Then, Howard asked if I wanted to run Phoenix? I said, “I never been on an oval in my life.” He said, “Well go on, find out how it is.” So, I went down there and promptly wrecked the shit out of the car, but I made the transition to oval track racing.

When was your first appearance at Indy?

Simpson: My first appearance there was in ’74.

And that was with what type of car? Who was your team?[pullquote]“…I’m tired of listening to your bullshit, you know, so I’m gonna light myself on fire.”[/pullquote]

Simpson: I was in an Eagle. I drove for Dick Beith. I was there actually, in ’73 I was there for Rolla Vollstedt with Janet Guthrie, she was my teammate and I was driving one of Rolla’s new creations. They called it the Bedstead or some…I don’t know. It was like an M16 McLaren. They did some really weird stuff to it and it had a lot of problems, and I had a pretty serious accident with the thing and that kinda stopped us from going further with that car. And Janet got in the show with her car, you know, she had a good one—she had the real deal.

Now, you took a year off in ’75?

Simpson: I did. Well, I didn’t take a whole year off, I took part of the year off. Simpson Safety Equipment, was way, way, way out of control. I don’t know what happened. We had made a whole bunch of different things and it was like our little company was sitting there in Torrance, California, and it needed help, so I spent a majority of my time there.

But you went back to Indy in, what, ’76 and ’77?

Simpson: Yeah, and in ’76 I got bumped. I qualified on the first day. It was about 100 degrees. I think they had about 104 entries or something like that; you’d have to look that up. I went home to California, I came back the next weekend and I qualified like at 184 or 185 miles an hour in the heat and I got in my car, the same car, everything was identical and I went out and I ran my third warm-up lap, you know, I ran 190. And I pulled in and I told my chief mechanic Ted Swantec, I told Ted, I said, you know if you guys are showing me the numbers, we had radios but I liked the chalkboard, I said, if you’re showing me that I’m running 190 mph, you might as well put the Milwaukee set up on this thing ’cause we’re not gonna be in this race. Which we weren’t. We got bumped. That’s because we didn’t have a backup. So, then, I went back again. I ran some races that year in that car. Like I ran Milwaukee and we had a pretty good finish, then I went and I ran Michigan and finished like 6th or 7th up there.

The next year Teddy Yip bought my whole race operation, so I ran with Teddy and we went to Phoenix and from Phoenix we went on to Indianapolis and Clay Regazzoni was going to be my teammate, which was fine, but Clay wrecked my car. I don’t mean just a little bit. I mean I was standing on the front straightaway in our pits and I saw the car above the turn four bleachers on the inside, up in the air, you know. I mean, he knocked the motor out of the car. One fuel cell was laying on the ground. It really was a big, big crash.

What was your best finish in that period?

Simpson: I finished 3rd in the California 500 in ’75, I think, or ’74. I don’t remember what year it was.

I understand there’s an interesting story behind how you decided to retire from racing.

Simpson: Oh, well, it was pretty interesting. I mean, you had your mind in two places and you can’t have two gods at one time, you know. And, my company was doing well and we were in the helmet business and that was taking up a lot of energy and a lot of brainpower and shit. And now I was going down the back straightaway at Indy and I wasn’t giving that whole thing 100%, you know, in fact I almost missed Turn Three.

Just thinking about other stuff?

Simpson: Yeah, it was like, OK, this is not cool and I pulled off and I came down the front straightaway on the inside and did another lap and I pulled in the pits. I got out of the car and I said, “That’s it boys; you’ll never see me in one of them things again.” And Gary Rovazzini who runs Ganassi right now—he runs Chip Ganassi Racing—Gary said, “What’s the problem?” You know, I says, if I can’t give you guys 100%, I don’t need to be riding around in that car. And my mind wasn’t there. I needed to make a phone call and I fuckin’ near crashed the car. So, I said, the best thing I can do is to step away from it because I’m a danger to myself and anybody else that’s on the racetrack. And I quit and I never did get back in one again.

Looking back now at your safety-gear business, you got started out making drag chutes, is that correct?

Simpson: Yeah, Jim Dietz is the guy that made the very first chute, like a surplus thing, and I made one, it was almost the same time, but mine was different than his. I tried the surplus parachute thing, you know, and it turned my car…I had a station wagon, I had it attached to and it turned the thing over!

We were going down a hill at 190th Street in Redondo Beach, which goes toward the beach and then you go way up this big old hill and you get to the top of it, then you didn’t have any cross streets going, until you hit Pacific Coast Highway. So haulin’ ass down that hill and all the way down that hill on the south side of 190th was a great big nursery. Anyway, we pulled this goddam parachute—we’re going about 110 miles an hour in the Chevrolet station wagon—and everything got quiet—it picked the back of the car up and the wind was blowing a little bit to the south, and we ended up rolling around out there in the nursery. Cops came and they took us to jail. I’m surprised it didn’t kill us both.

After starting with the chutes, where did the business go from there, in terms of how you started developing other products?

Simpson: Well, I mean, the parachute thing was kinda like a thing I was doing in my garage. But, I’d make a parachute in my garage and I’d sell it for $75 and that would get me through to the next week’s races. And, you know, it was really not anything serious. However, after a couple of years, I could see that those guys were really getting fucked up in drag racing and then I would go out to Ascot and watch the sprint-car guys and, about every other week, one of those guys was eatin’ it, you know; so I started paying way more attention to it. In fact, at Pomona in ’62 or ’63, Chuck Browning got burned to death out there. So, that made a hell of an impression on me, you know, and so I made a fire suit—very crude—but I still made a fire suit and that’s how that thing started.

Now, I heard a story that you somehow got involved with the design of the umbilical cords for the NASA space program?

Simpson: Yeah, I did that, all right.

How did that come about?

Simpson: Well, because Pete Conrad was a really good friend of mine. I got involved with Pete Conrad because Pete was an SCCA racer and he ran Formula Bs. And him and Rathmann were pals, Rathmann being from Indianapolis, and those guys went and did a race in the Bahamas and then they did one in, I think it was in Puerto Rico or something. And that’s where I met them. I really got along good with Conrad. He reminded me a lot of me, except he was older and I liked him and, you know, we became instant friends. He would turn me on to a lot of things and he opened the door for me to be able to communicate with the guys at NASA that are really smart. I’m not so sure that’s the way it is today but in those days, there were people that were pretty switched on and they were all car buffs. So, that’s how I ended up in the Nomex fold.

Photo: Simpson Collection

What exactly were you doing?

Simpson: Well, there was a fellow who was from Ventura, California, his name was Ed and he had developed a knitting machine. And this knitting machine would make…you know what an Aeroquip line looks like? It made the same kind of thing, but if you didn’t have a hose in the center of it you could pull on it and it wouldn’t tighten like a Chinese finger knot. You know, you can take a piece of nylon and stick it over your finger and you can pull on it, and what happens, it keeps tightening up, tighter and tighter? OK, well, he made a knitting machine that would prevent that from happening. And I just simply took that to NASA. Man, and they said, “Well, goddam, this is really something.” So this cat made this machine, and I said, what’s the good of that thing? And he goes, well, I don’t know, I just made it…. You know how shit happens? And I was telling Pete about it and he goes, “Are you telling me that it’s like a hollow piece of nylon, a braid and you can pull on it and it doesn’t tighten up?” I said, “Yeah.” He goes, “Shit man, that’s what we’ve been looking for.” So that’s how they got it.

So you were just kind of the intermediary to put the people together?

Simpson: Well, I helped them do stuff with it you know, to fabricate pieces and parts. I wasn’t the…I’m not smart enough to figure out how to make a knitting machine that would do that. That’s not my business, you know.

But, your relationship with Conrad and NASA ultimately led to your introduction to Nomex, which then led to better suits?

Simpson: Yeah. In fact, I ended up going to DuPont in Wilmington, Delaware, and I had a meeting with the president up there and he said, “Well, we can only make 3,000 pounds of Nomex a year.” They didn’t see a future for it. But I said, “No, you’re wrong.” Because I could see this going to the forest service, I could see it going to all the services for fire-protective clothing. And he goes, “Well, what’s your estimate that you’d, what would you think that we would do in this?” And I says, “Probably 25,000 pounds a year.” Well, they make about 10,000,000 pounds a year now, so that tells you how far off I was.

You started developing your Nomex suits, but at what point in time did you decide that it would be a good idea to light yourself on fire in one?

Simpson: [Laughs] Well, that was in ’71 when I did that, and that was kind of like a lark, you know, ’cause A.J. Foyt was giving me a bunch of shit. I said, I’m tired of listening to your bullshit, you know, so I’m gonna light myself on fire. But that was a kind of a candy-ass light, where we poured a little gasoline down around my feet and lit it on fire. But in ’88, we did it right. Over those following years, we went from Nomex to Nomex 1, 2, 3, Nomex 3A, Nomex 3A Plus. You know, it just kept gettin’ better and better and better. DuPont really, really did a hell of a job with that. So I came to the speedway, it was either ’86 or ’88, and I had a fire suit that was about half the weight of the one the year before.

So anyway, there was a guy there and he was wandering through the garage area telling everybody that I was full of shit, I was lying, and my product wouldn’t do what I said it would do. And at the speedway, the word gets back to you within a couple of minutes when somebody’s in there, you know, stirring the shit that doesn’t belong there. So, I just, you know, I said to somebody, point him out when he walks by the garage area, you know, when he walks by my shop here; they pointed him out, I went out and I said, hey, man, you know I know what you’re telling people about me and I don’t really appreciate it. Then he goes, well, that’s what I think. And I said, OK, you know what we should do? Let’s just have a burn-off this afternoon. He goes, a what? I said, well at 5 o’clock, when they close the track, we’ll go across the street over there and we’ll have a burn-off in the parking lot. And he goes, are you crazy? And I said, no man, you’re telling everybody my shit don’t work and yours is all like beautiful. I’ll meet you over there. So, I went over there. But, the word spread through the garage area, I was gonna do that. Well, I go over there, it was about 6:15 and there’s got to be 200 people there and half of them are the press. So I sat down in a chair and a friend brought a gallon of Mobil gasoline. They poured it on me and Chip Ganassi threw the match in and that son of a bitch went off and I’ll tell you what, you know, it was pretty spectacular from where I was sitting—and it was pretty spectacular from outside too! So, that’s how that came about and I don’t know, they put it out in about 30 seconds or 40 seconds. That was enough. I learned a good lesson, you know, that if you have a clear shield on and you’re in a fire, you’re gonna burn off all your eyelashes.

I didn’t know that.

Simpson: Yeah, well, lots of people don’t know that, but it’s true.

Looking at the amateur racing scene today and, in particular the historic racing scene, what’s your feeling on the current state of safety and safety gear?

Simpson: Well, I don’t really have any comment about that ’cause I haven’t really sat down and paid a lot of attention to historic racing specifically. I love watching them old cars race. And when I say old cars, they are “old cars” to a lot of people. To me, I mean those things are a piece of art, you know. I’ve got a couple of old racecars. I wouldn’t sit in one because I think they’re kind of inherently dangerous, but the vintage guys are doing, they’re doing what they’re supposed to do. They’re wearing all the right stuff. I don’t have an issue with that at all. Car construction and such, I can’t really make a comment about that.

Do you think amateur racing, in general, is keeping up on safety in the same way professional motor sport has been?

Simpson: I think—really honestly—most upper-echelon sanctioning bodies are pretty much keeping up with it because, you know, they can’t afford to be killing anybody. You can’t change a car design, you know! You just can’t do that. There are things that you can do to make it better and safer and, for the most part, I think that people are very interested in that, where 25 or 30 years ago, they weren’t. So again, I get a lot of people asking a lot of questions, and we’ve learned a hell of a lot over the last 25 or 30 years about how to keep somebody from busting their ass. You know, the primary things are to keep them in a good seat and keep them so they’re not moving around. So I have no issues with vintage racing. And I don’t have any issues with SCCA.

If you could peer into your crystal ball for a moment, what do you see as being the future trends in safety, say over the next 10 or so years? Not necessarily what’s in the pipeline right now but, theoretically, do you have ideas of where you think the direction of things may go in the future?

Simpson: Well, you know, I do. I think that we’re gonna come to a capsule in a chassis where if there’s a catastrophic crash, the capsule leaves the car and the driver’s strapped into it because then, once he leaves the car, all the energy’s gone and he’s just in there for an E-ticket ride. I think that racetrack safety is gonna improve a tremendous amount. I think that as far as drivers’ personal safety equipment goes, it’s at the cutting edge but I don’t see it making any huge advances.

You don’t see any new technologies on the horizon?

Simpson: No, I don’t really.

Not another Nomex, or similar advance that revolutionizes the sport?

Simpson: Well, because right now, you know, you can make a fire suit that only weighs 3 pounds. I don’t see how the hell you’d want it to be any lighter than that. Now, I know we’re dealing with some atomic scientists out in Rhode Island and they’re talking about this nano fabric, fabric made with nano fibers. They’re talking about making a piece of material that does the same thing that a piece of 7-1/2-ounce Nomex does that weighs micro ounces. But, that’s a ways away. You know what, there are a lot of things out there on the horizon but, like you say, it could be 10 years from now, it could be 5 years, it could be 20 years from now. We are on top of most of that stuff that’s going on, I can assure you.