The automobile is perhaps the single most consistently recognized cultural artifact of modern civilization. And while the cell phone or television might give the car a run for its money, the depth of passion and engagement with the automobile is far more universal and emotional, with a greater impact on our culture and geography, particularly over the past 100 years. Prior to the automobile, most citizens remained within 25 miles of their home as traveling was generally limited to daylong journeys by horseback. This not only limited our scope of personal adventure, education, and cultural expansion, it limited the genetic diversity needed to build a stronger and healthier humanity outside of small close-knit familial communities. As the car grew cheaper and readily available for use, families not only expanded, businesses expanded dramatically, small businesses including grocery stores, fuel stations, and repair shops all catered to both institutional and commercial interest in the automobile.

Although Cadillac had offered an electric starter for their cars as early as 1912, it was not until 1919, when Ford offered it in the Model T that electric starters significantly changed widespread use of the car. Concurrent with the women’s suffrage movement, the automobile—previously needing a strong arm for hand cranking—could now be started by women and driven independently to and from multiple destinations.

The electric starter not only offered emancipation to women, it offered adolescent men and women a chance to take the wheel and help with deliveries from rural farm communities into cities. The advent of the electric starter for gasoline powered vehicles also allowed for medical doctors to travel further than the limited local range of their electric car. Most doctors purchased the electric car (often referred to as the “Doctors Coupe”) because they could not risk losing a surgeon’s arm on a rapid recoil from a starter iron kicking back. If you’ve ever tried to start a hand-crank car, you’ll surely appreciate that it takes both skill and strength to avoid getting hurt.

But it wasn’t just the ability to move around, the new-found durability and social value of the automobile soon replaced the bonds we once had with our horses. Formerly our animal partners, we would return home after a long ride, bathe the horse, groom them, check their hooves and shoes, inspect their muscles for any swelling or signs of stress, leave them safely overnight to rest, and then tend to our personal needs. Nearly all of these behaviors translated to our social interactions with the car, including bathing (car wash), checking the hooves (tire wear and pressure), inspecting the musculature (checking the body and paint), and stabling them overnight (parking in the garage). Our former relationship with an animal was now transferred into a non-animate object. Other than the horse to car relationship, I’m unaware of any other sustained animal relationship that has happened within the duration of our species. We’ve seen robotic dogs, but certainly not by the millions. No wonder there is so much universal affinity for the car and little emotional attachment to a toaster, blender, or lawn mower.

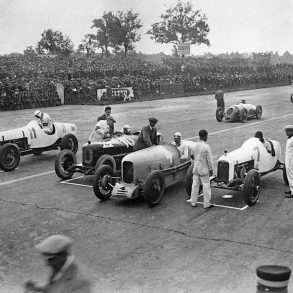

With the end of WW1 and rapid growth in burgeoning cities, the automobile became a symbol of wealth and adventure. For nearly a decade through the 1920s, wealth among commoners without royal status or as part of landed gentry, became more prevalent. Many of these newly wealthy young men and women used their automobiles as status for a new class of wealthy elites; the sporting class, including motorsports, rally racing, and hill climbs.

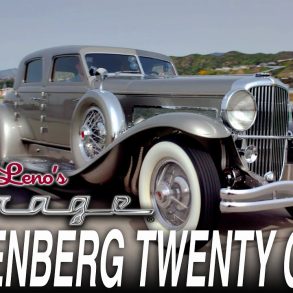

The automobile built new clothing fashions, new language usage “My goodness! that’s a Doozy.” (attributed to the Duesenberg), and new ways of living including camping by car and traveling across the continental United States via the automobile. By mid-century the automobile made yet another statement of cultural impact with the Fiat Topolino, VW Beetle, Citroen 2CV, and Mini Cooper. These now iconic economy cars set the stage for decades of simple but durable everyday transportation combined with quirky but endearing popular charm. Each of these cars were not only reliable and thrifty, they were often loved with animal affectation, with many owners embracing these cars like members of the family.

And while the massive 1950s post-war highway expansion is well known, what is not always appreciated was how much the automobile literally built places like Las Vegas, created town after town across rural America, formed the basis of middle class communal dining outside of the home, and launched numerous creative exploits including hot rodding, dune buggies, drive-in theaters, lead sleds, Kustoms, recreational motorsport events, low rider culture, fiberglass sports car kits, do-it-yourself camper conversions, full-sized van conversions, and a wide array of other significant cultural movements, all of which were predicated on the cultural impact of the automobile.

Today, we sit on the precipice of yet another cultural revolution in the automobile industry. The transfer of our formerly self-guided destiny of beauty and movement to algorithmic response software that will ultimately guide and propel us to a predetermined driverless future. The roads will remain, the roadside architecture will change, but the behaviors, trends, and fashions of our motorized yesteryear will forever be altered by the shifting content of aggregated decisions derived from computational analysis. We will even begin to believe that the choices our cars make will be our choices, simply by way of the familiarity of those algorithms.

Fifty years ago, the notion of a car that could park itself, contain a telephone, or access billions of segments of information and entertainment at our fingertips, were all but science fiction. Within the lifetime of most of us reading this article, we will arrive in cars that will take us wherever they want. They will encourage us to eat a burger when they pull into the drive through, or have a coffee, or pull into the doctor’s office for that annual checkup we’ve been avoiding. Why? Because our insurance company, fast food collective, or coffee franchise will be buying influence on the algorithms driving our cars. They won’t just drive our destinations, they will drive our decisions. But, fear not brave collectors of vintage cars, as we tighten our grip on the soon to vanish steering wheel. We will still hold on to our ancient relics of the past, filling our tanks with specially purchased fuel, charmingly started by key, running petrol engines, with fumes flying freely, heading for serendipitous destinations without maps or software, much like we once did on the backs of our eager horses.