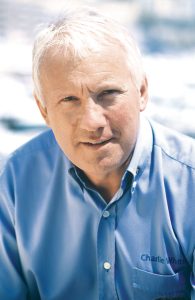

FIA Safety Delegate

Any organization is, in truth, only as good as the people in it, and motor sport’s global governing body, the FIA, is no different. One of the men who help make a difference there is Englishman Charlie Whiting. Whiting started out in Club racing and worked his way into Formula One where he served with Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham organization, helping guide Nelson Piquet to a pair of World Championships. As Ecclestone moved from team management into government, he needed to keep men he could trust around him, and one of those was Charlie Whiting who, as FIA Safety Delegate, is charged with guarding and advancing the safety of the sport. It was wearing that hat that he sat down with VR European Editor Mike Jiggle to discuss this month’s main topic—and his personal path to his present position.

Your early motor racing experiences were with your brother Nick in the All Car Equipe team. Nick did the driving, and you were the mechanic, was that something agreed upon?

Whiting: I always fancied myself as a bit of a driver, but never got around to it. From the age of about 12 years, I helped my older brother Nick in his garage. He had a small garage and repair business. In 1968, when I was 16 years old, he did a bit of autocross racing and the racing thing developed from there. Nick progressed to rallycross racing, until 1972–73 when we entered circuit racing. That’s roughly how it all started, so you could say my racing mechanic days evolved from that.

The All Car Equipe were quite a successful team; and a firm favorite with the fans, especially at Brands. What was it like taking on the likes of Gerry Marshall and Co.?

Whiting: It took us quite a while to beat Gerry, but we did—on April 20, 1974. It was a remarkable day for us, a little team beating what we perceived to be a works team. We got better and better, and for sure Gerry was the man to beat; I think we beat him quite a lot from 1974–’76. Of course, he got himself a more powerful car; we built our own for the 1977–’78 seasons and contested the British Super Saloon Championship, which Nick won and was champion in 1978—it was his most successful year. If my memory serves me well, I believe Nick won all 48 races he contested in the All Car Equipe MkII Ford Escort, with the 3.4 V-6 engine.

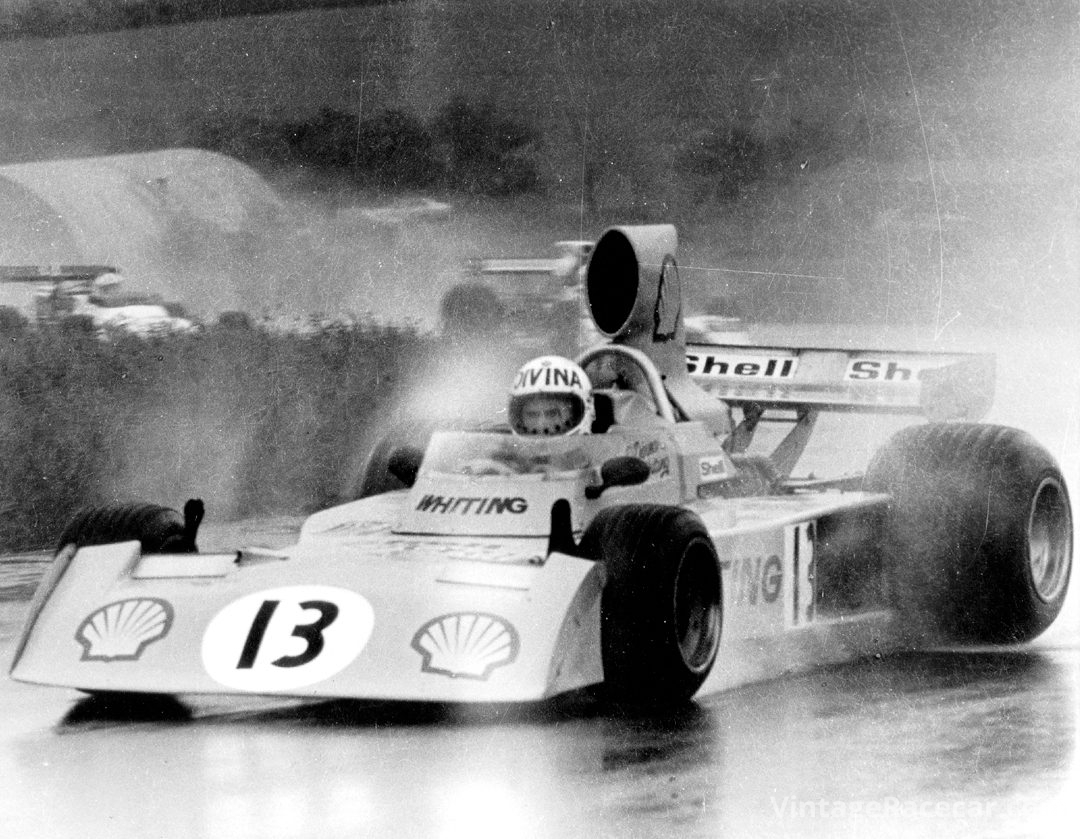

In 1976, the Whiting team ran Davina Galica in a Surtees for the Shell Sport European F5000 series. It must be acknowledged that the series was in decline and other cars including F1, F2, and F Atlantic cars were invited to pad out the grids, but you finished 4th in the championship, no mean feat for a small team.

Whiting: Yes, we ran Davina in parallel to our own racing program. We started with a Surtees TS16 and moved on the following year to a TS19. We had a couple of 2nd places, quite good results. Davina was quite a formidable woman, very accomplished; don’t forget she was a former downhill skier. Her driving was similarly accomplished. I don’t think she would have been a Grand Prix winner—even in the best equipment—but she was a force to be reckoned with and did well in her races for us.

Then there was a split in the ways; you left your brother Nick and found yourself at Hesketh. The champagne days of James Hunt were over, and they were battling to stay in Formula One. How did that come about?

Whiting: That would be the end of 1977; Davina wanted me to continue being her mechanic when she entered F1 with the Hesketh team. I agreed and left Nick. It was, however, a somewhat ill-fated foray into Grand Prix racing. We didn’t qualify for one race; it wasn’t a bad car but, obviously, it wasn’t the best. Davina couldn’t really make the grade; I think we ran Eddie Cheever in South Africa, and Derek Daly for the next three races in America, Monaco, and lastly Belgium; they couldn’t qualify either. I think it showed that the car was the problem rather than blaming Davina for its inability to qualify. The team folded after that due to lack of funds. Lord Hesketh hadn’t the cash anymore; Davina took the Olympus Cameras sponsorship with her to Hesketh, a company that supported her in the F1 Surtees TS19 the previous year, but that wasn’t enough.

Then you joined Bernie Ecclestone at Motor Racing Developments International, or Brabham, the start of what has become a long relationship with him. When did you first meet Bernie?

Whiting: In June 1978, after the Belgian GP; I was looking for a job. Dave Simms, team manager of Hesketh, put me onto Herbie Blash at Brabham. Herbie invited me for a chat, although he told me he didn’t really have any vacancies on the race team. I went to meet him and he gave me a job with the Brabham test team. The test team comprised of two people, a Mercedes van and a trailer, very meager to what you might imagine. The first test was in Austria; off we went with van and trailer, and completed our duties. The next Grand Prix was in France; I was put on the “T” car of the race team and that was it, from then on I stayed with the full race team. I’m not sure if someone left, or what, it didn’t matter to me, I was on the race team full time.

I continued on the T car for the 1978 and 1979 seasons, until being promoted to number one mechanic on Nelson Piquet’s car for the 1980 season.

There were political rumblings in the sport, and the start of what was to become the FISA-FOCA (Formula One Constructors Association) war. Bernie became president of FOCA, standing up for a better deal for all teams—not too dissimilar from today; amazing how history repeats itself.

Whiting: Quite frankly, I was unaware of what was going on outside the team—politics or otherwise. Obviously, Bernie was on the FOCA side of things in the initial stages. As time went on his negotiating skills saw him elected as a vice president of the FIA.

Niki Lauda joined the team, as the current world champion. What did he expect from the team?[pullquote]

“In those days, safety was still in its infancy; until Zolder, no one talked about it.”

[/pullquote]

Whiting: I wasn’t there until later in the season, as I had joined after the demise of the Hesketh team. So, Niki was there prior to me. I didn’t have too much to do with him then, to be honest; he was very aloof. We have spoken many times since then; he’s a different person these days, basically he fell in love with the Brabham car— obviously there was some financial inducement, too. We had a reasonable 1978 season. Niki didn’t do too badly—his driving at Monaco was brilliant. Just over half distance had gone, Niki was in 2nd place behind the Tyrrell of leader Depailler, one of his rear tires started deflating with a puncture, he came into the pits and was “turned around” quite quickly. He lost places to teammate Watson, Scheckter, Peterson, and Villeneuve. From then on Niki charged, finally finishing in 2nd place; he was stunning.

Let’s look at the Brabham “Fan Car.” It was a prime example of how rules were exploited to obtain maximum downforce. What were your thoughts at the time?

Whiting: Again, as a mechanic, I didn’t get involved too much with the politics of the sport. We just did as we were told. Personally, at the time, I thought it was a brilliant concept—and to get it to work was a great bonus. There were many problems to overcome before it worked properly; however, it did and won the Swedish GP. It was a miracle that it all held together for the race, but, it was so much quicker than anything else. After the race, and back at the factory, I remember men in blazers from the FIA came around and checked things out. After they had made their observations, Bernie withdrew it from further competition. Fundamentally, everyone was flirting with the idea of running “skirts” down the side of the car—Lotus took that idea to new levels with sliding “skirts.” At Brabham, we had flexible “skirts,” not only along the sides but at the front and back sealing the whole area. We then added this whacking great fan on the back that sucked air in through the radiator and cooled the car. Our contention was that the moving part, i.e., the fan, had a primary purpose of cooling the engine. It was incidental that it sucked the car to the ground!

And, in Hindsight?

Whiting: Clearly, it was a very neat scam, and it worked, a little too well. I had the feeling that Bernie was happy to get away with one win from this idea—which was very crude. Of course, if one let this system become more and more refined, who knows what it could have led to? The FIA would have done something about it if Bernie hadn’t.

During 1979 Lauda become more and more frustrated, resulting in him walking away from the team and the sport during qualifying for the Canadian GP, the penultimate race of the season. Piquet, alternatively, seemed to get his head down and show promise in what can only be described as a difficult season. Was this to do with the relationship with Alfa Romeo and a move back to Cosworth?

Whiting: In 1978, it was very apparent the relationship with Alfa was good, and we were happy with the flat 12 arrangement, but the following year we wanted to move to a V-12 engine to assist with our new Brabham BT48 “wing” car design. Unfortunately, the V-12 was just an awful engine. Alfa compounded the problems too; engines would be delivered to our factory very late, and details of the engine design would differ from the spec, i.e., an oil pump would appear in a different location than the original plan; nothing would be said about any change; it would be something we would find on delivery. Things became very strained; eventually the whole rapport between us and them just collapsed. Gordon (Murray) came into the workshop one day and informed us that from the following race we would be using Cosworth engines. The new engine was fitted into the new BT49 design and tested at Thruxton; it was a wonderful little car in comparison to the BT48, and was immediately quick. Nelson loved the car; he was immediately quicker than Niki in Montreal, its first outing. For one reason or another, Niki left the team, he had had enough.

Nelson was very young and enthusiastic; I never really got to the bottom of why Niki called it a day in Montreal. Yes, he had had a pretty poor year with the BT48; he did win the non- championship race at Imola, admittedly by a miracle. I’m not really sure what actually happened, all I remember is that his kit bag was missing between practices at Montreal. Someone said to me, “Niki has gone.” I said, “Don’t be silly, his practice starts in less than ten minutes.” I was working through the job list Niki had given us, and I realized, yes, he had gone. Looking back on it, to this day, I still don’t know what happened, and I’ve not talked to Niki himself about it either.

Piquet’s confidence grew over the next season or so, and in 1981 the team provided him with a car to get the job done.

Whiting: Yes, we almost got the job done in 1980. I still think, to this day, if Alan Jones hadn’t punted Nelson off at the first corner n Montreal, we may have had a chance that year, too. Jones was a very tough driver. Nelson wasn’t. Nelson had been amazingly quick that weekend. After the crash, which started with Jones running into Nelson, there immediately followed another incident that entangled most of the other cars. The race was stopped. Nelson was able to go out again in the T car for the restarted race. For reasons I wasn’t involved in, the qualifying engine had been left in the T car. A qualifying engine, at that time, was a completely different spec to a race engine; of course, in the restarted race, although at first very quick, it didn’t last and Nelson retired. Had we won that race we could have gone on to Watkins Glen and fought out the championship with Jones. In 1981, by the skin of our teeth we did it.

At the 1981 Belgian GP, Zolder, an unfortunate accident claimed the life of a mechanic in the narrow pit lane. The result was a drivers protest prior to the race. All the drivers got out of their cars and stood shoulder to shoulder with the mechanics— probably the first public demonstration of solidarity by competitors and teams that something should be done to improve safety at a circuit.

Whiting: Yes, it was Carlos Reutemann who hit an unfortunate mechanic in the pit lane. It was a narrow pit wall, and he stepped off it into the path of Carlos; there was nothing Carlos could do to avoid it.

The race started and Patrese’s Arrows stalled, his mechanic, Dave Luckett, jumped onto the track and tried to restart the engine. All the cars avoided a collision with Patrese, except teammate Siegfried Stohr. Although completely foolish, at the time adrenalin pumping with all involved, is it something you would have considered doing if Piquet’s car had stalled?

Whiting: Probably yes, you only thought about your car, you were passionate about it. Yes, it’s something many people would have done at that time without considering the consequences of their action. In those days, safety was still in its infancy; until Zolder, no one talked about it. Had it have been now, no one would have dreamed of doing such a thing.

As for Dave, I really thought he had been killed, as I happened to be standing very close to the guardrail beside the car.

Riccardo Patrese joined the team in 1982, up to that point he had had a hard time. James Hunt always blamed him for Ronnie Peterson’s fatal accident at Monza in 1978; the court case in Italy cleared him in 1981. How did he seem when he first came, was he a bit battered and bruised, did he need an arm around his shoulder?

Whiting: No, I don’t think he did. He was very quick; we all liked him, and he was a great guy; we all got on very well with Riccardo.

We cannot pass by 1982 without mentioning the German GP where Piquet punched Eliseo Salazar after Salazar had taken him off. Were you aware of the incident as it happened?

Whiting: We saw it unravel on TV, we were ready for an impending pit stop; it was only the second race in which we had attempted to carry out refuelling. We were preparing for that. On the track, Nelson was aware he needed to push to get a decent lead to accommodate lost time for the impending pit stop. On reflection, the incident was as much Nelson’s fault as Salazar’s. However, at the time, we all supported Nelson. It goes back to the adrenalin and passion of the situation, and something happening to your car.

It’s said that if a car looks good, it normally is; the 1983 Brabham BT52 was dart shaped and extremely quick. It certainly looked the part, and it did the job, too.

Whiting: A stunningly brilliant car. It was the first year for flat- bottomed cars, a total ban on ground effects from previous seasons. It was a brilliant piece of design; when you think about it, all the weight was rearward. BMW worked with us to the extent that they had a new engine for each race; within a matter of a few minutes, by undoing four bolts, disconnecting and reconnecting a couple of wires, we could drag out the radiators, intercoolers, and change the whole of the rear end. We had new rear ends already built and waiting for use. Ultimately, this gave us supreme reliability, which all teams were striving for, and was a major factor for winning the world championship.

Even by today’s standards I think it’s a magnificent looking car…

Whiting: I agree; it’s just one of those iconic cars one always remembers.

Nelson Piquet had won his second world championship; it is always difficult to string championships together (unless you’re Michael Schumacher). What are the difficulties?

Whiting: I think it was the change from Cosworth to BMW engines in 1982. We ran two cars with Ford engines and two cars with BMW for half the season, and the whole thing was too much. Strangely enough, we did Monaco, Canada, and Detroit, with two and two—that was two Fords for Riccardo and two BMWs for Nelson, and we won two of those races, Riccardo winning Monaco and Nelson winning Canada. In Detroit, Nelson didn’t even qualify; such were the initial reliability problems with the BMW engine. Once we went completely over to BMW, unfortunately, our season was one of unreliability. We had very good practice performance, but the race was a different story; for instance in Austria, Nelson took pole by about three seconds, but in the race the engine didn’t last the distance and he retired.

Piquet left for Williams at the end of 1985, and was replaced by Elio de Angelis. Tragedy struck at the Paul Ricard circuit when a rear wing failed causing de Angelis to crash. It is said he could not get out of the car, otherwise he may have survived. What’s your view?

Whiting: I wasn’t there, but my understanding is that the car had very little fuel in it; it rolled end over end, over a barrier, and ended upside down. I think the post mortem showed he was virtually uninjured; a relatively small fire started and asphyxiated him.

From then on it seemed that the team was on a downward spiral, perhaps Bernie had taken his eye off the team and a more political future was being mapped out.

Whiting: At the time, we just got on with our work and nothing appeared to be wrong; looking back, I can see we were falling back. The BT55 wasn’t a good car, the theory of getting the car really low, the “laid over” engine and all that sort of thing was really good. However, the chassis had all the torsional stiffness of a warm Mars bar. BMW thought it was a chassis problem; Gordon thought it was the engine. To me, even at the time, I thought it was an irreconcilable situation. From that time on, the relationship with BMW went downhill.

The next year we had to use the same “low line” engine for the new BT56; David North and Sergio Rinland were responsible for its design; it wasn’t a bad car. Our drivers were Riccardo (Patrese) again and Andrea de Cesaris; Andrea was a nice guy, I liked him, but, in driving terms he had a checkered history.

I always thought, in racing terms, he wore his heart on his sleeve and managed to get himself into situations he shouldn’t have been in…

Whiting: He was a nice guy when he was out of the car; when he was in the car he was a bit of an animal, nonetheless a charming guy. He and Riccardo didn’t get on too well, they were Italian, Andrea was from Rome and Riccardo wasn’t—that was the problem. Riccardo hated him just because he came from Rome; they were never going to be “best buddies.” Riccardo was very professional about it though, and got on with his job—similar to when Elio (de Angelis) died; he was in a state of shock just like the rest of us, but got his head down and got the job done. Both drivers had a podium finish during the year, Andrea in Belgium and Riccardo in Mexico.

The following year the team took a sabbatical. You joined the FIA as Technical Delegate in 1988. What did that role involve?

Whiting: Bernie said he wasn’t going to run the team in 1988 and told me he had “a good idea.” From our conversation, as you say, I joined the FIA technical team, I was not the Technical Delegate—that was Gabriele Cadringher, I assisted him in weighing the cars and a few measurements, the checks were pretty simple in those days. Little by little, Gabriele got more involved in rallying and other duties; when he decided he couldn’t fit everything in, I became Technical Delegate.

The cars became more and more complicated and technical; I didn’t think the wooden jigs we used to verify measurements were appropriate in these surroundings. It’s very archaic to see a wooden frame being jammed over the rear of a highly complex Formula One car; it just wasn’t acceptable anymore. I came up with new sophisticated ways to inspect the cars more in keeping with the precision the cars were built. Gradually, I built up a team, as the “new way” of checking the cars wasn’t something to be taken on single-handedly; over the years the job has escalated to where we are today. A far cry to where I started!

Personally speaking, 1990 was a tragic year for you; your brother, Nick, was found murdered. Is that something you want to talk about?

Whiting: I don’t mind talking about it; of course, it was a shock for us all—a horrible thing to have happened. Obviously, it was a bad year; it wasn’t as if he had been killed in a car accident. It was a long drawn-out affair. He went missing for a few weeks; his cars were missing—fundamentally, he got involved in something that was far greater than he anticipated. Unfortunately, the police didn’t have enough evidence to do anything about it.

Talking of dark days, and I know it’s before your time as Safety Delegate, but can we have a look at that black weekend at Imola, first Barrichello’s crash, the next day Ratzenberger, and on race day Ayrton Senna’s death. What was your role, if any, in the subsequent proceedings?

Whiting: At the time, very little.

Barrichello’s accident was just a mistake—he went over a curb which, by today’s standards, was far too high. It launched the car, and then bang, bang, bang—luckily he was okay.

Roland Ratzenburger lost a front wing at possibly the most critical place on the track. As far as we were concerned, it was just a very unfortunate accident.

With Senna, the accident happened, and we didn’t know how serious it was. Afterward, the ramifications were massive— something had to be done.

There were knee jerk changes to most circuits; not always for the better, or, on reflection, safer?

Whiting: In my opinion the tire-walled chicanes that were put in at Barcelona and Canada were the worst things—it leaves me speechless. We had an emergency meeting in Paris a few days after; there was Roland (Bruynseraede), Max (Mosley), myself, and a few other key people of the time. We discussed the incidents and events of the Imola weekend and couldn’t find anything that connected them. To me, that was a very rational and calm way of going about it. When the FIA made a statement on the Wednesday following the accident stating there was nothing too wrong with Formula One, some people couldn’t cope with it.

After that we had Karl Wendlinger’s accident at Monte Carlo, just a few weeks later.

Whiting: Yes, I remember a headline in a French newspaper— “This Madness Must Stop.” Again, Karl’s accident was very unfortunate; it wouldn’t happen in one of today’s cars with high cockpit sides, but an unrelated incident to those at Imola.

At that point, we decided something had to be done. We chopped some of the underwings off of the cars, and there were many other things we did, a big list, I can’t remember all of them now. Then, Andrea Montermini crashed his Simtek during practice for the Spanish Grand Prix, Barcelona—again, totally unrelated to the other four. He just made a mistake, went off, bang, hit the wall, and bent the chassis. The front of the chassis took the brunt of the accident, and he suffered injuries to his ankles. It all calmed down from there on, thank goodness; there was a bit of a “who ha” when Max changed some of the rules at short notice—Max was completely unrepentant! Improvements made in the 1995 (the stepped floor) and 1996 (the high head rests) seasons, possibly, wouldn’t have happened as quickly if 1994 hadn’t happened.

Photo: Maureen Magee

There have to be many compromises to run a Grand Prix at Monte Carlo. Is it tradition, money, or is there another reason for it still to be a part of the calendar?

Whiting: There are two things to consider at Monaco. First, the speeds are relatively low, today’s car are extremely safe, and second, there is a very good argument for having barriers so close to the edge of the circuit because an accident will happen at a very much shallower angle. Where you have the highest speeds, at St. Devote and the chicane, we do have significant run-off areas. We examine speeds perpendicular to barriers, where there are impacts, obviously the shallower the angle the lower the perpendicular velocity. With older circuits, there often are things you probably wouldn’t consider for a new circuit.

If someone proposes a street circuit now, like Singapore and Valencia, we would look at it differently. We do our best to have sufficient tire barriers in significant places, debris fences are renewed every year, we try to do everything we can to make it as safe as possible—in some cases we can’t have massive run-off areas but impact-absorbing barriers are quite advanced these days and can be used where distances are not optimal.

In 1997 you became the FIA Safety Delegate. What are your responsibilities? I came to visit you at Silverstone on the Thursday prior to the 2009 British GP—you were walking the track. Most people believe you’re responsible for pressing the start button and that’s that.

Whiting: Today, I’ve got three titles: Starter—obviously, that bit doesn’t last very long; Safety Delegate; and Race Director. Safety Delegate relates to the condition of the circuit prior to the race weekend and maintaining its condition throughout the duration of the event. On the Thursday we always do a final track inspection prior to the race weekend. I would normally have been at the circuit a couple of months before the race to note and be informed of any changes since the previous year. I have to make sure any changes meet with FIA approval. The Thursday track inspection is looking at all the smaller points, sharp curbs, positioning of verges in critical areas, those sorts of things. Obviously, “big stuff” is done and agreed before hand. It has to be a very detailed thing, to make sure everything is right; if anything happens during the event, we have to make sure the circuit is maintained and put back to its original secure condition.

Race Director, includes briefing both drivers and teams, running practice sessions, making sure the timetable is adhered to, making adjustments when necessary, advising when the safety car should be “on track,” all those sorts of things; it doesn’t keep you that busy! However, I’m also head of the FIA Technical Department, and as such have to deal with all technical issues as and when they arise. I have Jo Bauer to assist me and look after our team on a day-to-day basis. The Brawn diffuser story at the beginning of the 2009 season was very much a matter that I was involved in. I deal with technical issues more between the races rather than at the races. However, if teams have any questions or enquiries I am there to answer them.

Modern racing cars are tremendously safe, even at high speeds. During the 2007 Canadian GP, Kubica’s car disintegrated into a thousand pieces—all except for the “survival” cell, which did its job. He walked away relatively unscathed, a testament to its design. Are we not coming to a period where driving standards could fall because of this safer environment? We have seen some dodgem driving over the course of the past few seasons. I was talking to Hans Heyer, a few months ago; he mentioned driving standards in the DTM. He saw, with regularity, drivers using cars already in a corner as a brake for them to take a corner faster—irrespective of the damage they would do to their fellow competitor, or his car.

Whiting: The latter incident is very much a saloon car approach to racing. I don’t get too involved with touring cars, and it’s therefore very difficult for me to comment upon.

What I’m trying to ask is, if safety standards rise, do driving standards fall?

Whiting: I don’t think driving standards will fall; I tend to think that driving standards in Formula One are very high. What I do believe is that, when they are on their own, they will take more risks, no doubt about that. If you look at the Turkish GP, Turn 8, if there was a barrier closer to the track, there would be far fewer cars going off—they see a large asphalt area and can’t help but use it—it’s almost human nature, I suppose. If the driver is a serious championship challenger, one DNF is enough to dent his aspirations. In the main, most are good at staying out of trouble

How does the FIA look at the accidents involving Henry Surtees and Felipe Massa? Do you think that the head needs more protection, or do you think that modern helmet design is suitable for its purpose and that both of these accidents were just freaks of nature?

Whiting: The Surtees and Massa accidents are being investigated with a view to learning more about what led to the injuries; this is a routine exercise for us at the FIA. Even though massive strides have been made in wheel tether and crash helmet design over the past ten years, we can never stop learning.

Leaving modern racing, what advice, in your capacity of FIA Safety Delegate, would you give to the modern amateur or historic racecar driver.

Whiting: I do see quite spirited driving in the FIA Historic Formula One Championship, however, I don’t believe the cars are driven nearly as quickly or as hard as they were in their hey day. It’s helpful too that the FIA Historic Formula One Championship is run on today’s very safe circuits. If I look at a typical car, the Brabham BT49, for example, it ran on a lot less safe tracks in period than it does today. In that respect it’s safer to run it now than when it did. Also we do have modern driver protection with race suits, helmets, and the HANS device.

Sir Stirling Moss has a special dispensation to wear an outdated helmet. Does this give the wrong impression to other drivers? On the other hand, David Brabham looked a little ridiculous driving a 1959 F1 Cooper wearing his 2009 Le Mans helmet and race suit to run up the hill at Goodwood.

Whiting: My very personal feeling is that drivers should wear the very best protection they can at all times.

What about the safety and security of historic racing cars?

Whiting: Once again, I feel a little out of my depth here; I’m not really “in the loop” on historic matters. I look, every other year, at the Historic Grand Prix races at Monte Carlo, and I have the utmost respect for each and every driver who competes. I’m in awe of these guys in those wonderful cars. In the end, motor racing is a potentially dangerous sport.

In my view, all competitors should always use the best available safety devices to keep them utterly protected at all times, irrespective of the nature of the car, driver, race, or championship.