After a bottle or two of the Marshall’s superb wine, we negotiated the acquisition of his 1939 Packard 120 convertible. Included in my entourage were Robert Escalante, owner of Custom Auto Service in Santa Ana, California, and his chief mechanic and foremost Packard authority, Cal Soest. After we concluded the deal, we retired to our individual en suites for the night.

The next morning the air was so fresh it seemed perfumed, and the scenery was stunning, but all of that paled to insignificance when I saw Justin’s 1939 Packard Eight convertible coupe. It had been rolled out of the garage at the top of the drive. Its Miami Sands paintwork made it look almost ethereal in the misty morning light, and its chrome sparkled in subtle accents. It was a car I had been fanaticizing about for years; a classic Art Deco era Packard convertible like the one Faye Dunaway drove in the movie China Town.

Granted, Dunaway drove a more expensive Super Eight in the movie, whereas the car I had just purchased was a mass-produced model dubbed simply the Eight, powered by a smooth 282 cubic inch inline-eight, while the Super Eight had a 320 cubic inch engine and 130 horsepower. However, the smaller 282, coupled to a Borg Warner overdrive is more than enough to allow you to cruise at freeway speeds.

My new convertible was an older restoration that was less than show worthy. And it had a few problems that I knew how to fix. But never the less, it looked stunning with its dual side mounted spares, luggage rack, and all the extras available at that time, including the weather-front, thermostatically controlled grille, deluxe pushbutton radio, heater and goddess of speed mascot.

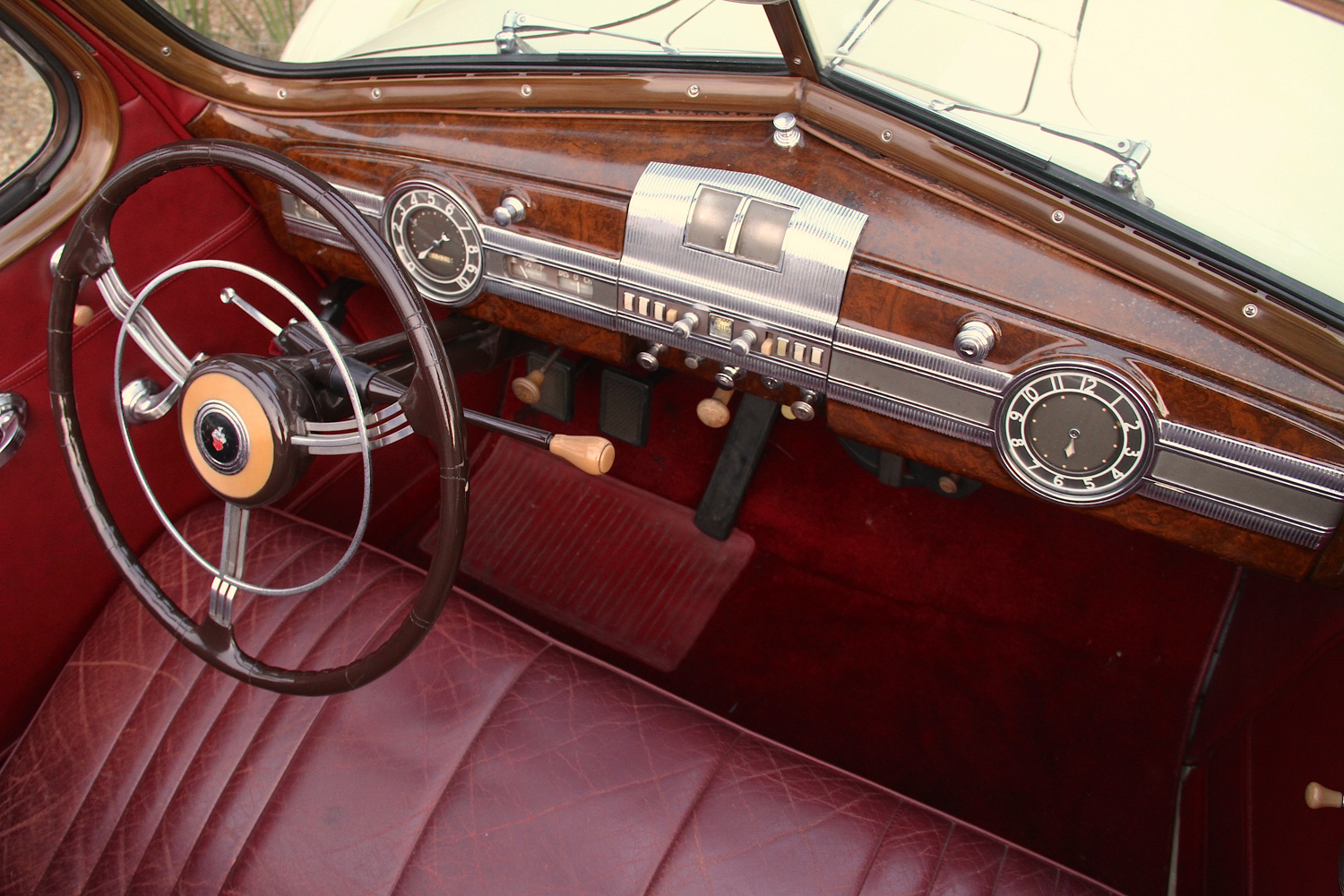

It was time to cast myself from this Garden of Eden before I wore out my welcome and head back home. We put the top down (it folds manually) and I slide in. I am completely familiar with the car because I have been a life-long Packard buff, and have owned several of the junior models from this era. The wide heavy door swings open and I climb in with ease. The cushiony wine-dark leather interior embraces me. I look out over the long hood with its lines making a narrowing sweep toward the goddess that is a Toyota Tercel length in front of me.

I tap the throttle to set the automatic choke and then step on the clutch, turn the key, press the starter button, and the engine comes discretely to life at a fast idle. It soon settles into vibration-free silence. It is so quiet that I am not sure it is running. I pull it into low gear; give it a little throttle, and it oozes silently away as quietly as an electric car.

Most people have never experienced the buttery smoothness and ample bottom end torque of an inline-eight. Some would see the inline configuration as obsolete, and even believe that the V8 superseded it, but the reverse is actually the case. The French had V8 engines in 1904, whereas Issota Fraschini introduced the first production inline-eight in 1919.

Also, a V8 is really two four-cylinder engines driving one crankshaft, and is not inherently balanced, so it can never be as smooth as an inline-eight. It is true that the V8 is a more compact and a lighter configuration. But the reason they stopped building inline-eights for production cars was that they were more expensive to produce.

When you consider that many inliners had nine main bearings and eight rod bearing surfaces versus the V8 with three main bearings and four crank bearings, you realize that the machining costs— the most expensive part of engine manufacturing—of an inline-eight were far greater than those of a V8 engine.

And lest you believe that the inliners weren’t competitive for racing, keep in mind that Mercedes used them into the 1950s in their Grand Prix cars, and they were untouchable, especially in the hands of the late great Sir Stirling Moss, and Argentine maestro Juan Manuel Fangio. Mercedes later retreated to inline sixes and continued to be competitive even when spotting the competition two cylinders.

Overhead valves were on the scene from the beginning in the late 19th century, but didn’t really dominate in production cars until after World War II when compression ratios were bumped up past 8.5:1. That’s because the L head could not handle compression higher than that due to combustion chamber configuration.

I start rolling and ease the transmission lockout cable into overdrive. The old convertible pulls away smoothly as I ease out onto the highway. I then shift into second, and at about 25 miles per hour I let up on the throttle for a fraction of a second and the transmission shifts into second overdrive. This is good to get me up to 45 miles per hour, at which time I pull the column shifter into high gear and wind it up to 50 or so. Another quick lift on the gas takes me into overdrive high and I run it up to 70 miles per hour and keep it there for most of the 400-mile drive back to Southern California.

The world is a different place in an open car. I smell the sage and the pepper trees along the highway, and feel the bracing breeze. And then as I near the coast, I smell the Pacific Ocean and enjoy its grandeur as the sun rises higher in the sky. The 80-year-old Packard glides smoothly along, and its large easy to read analog gauges tell me everything is as it should be. The speedometer is as big as a saucer and has a needle almost the size of a pool cue.

The car’s steering is light and effortless on the road, and bumps are only discretely implied. Even with the top down I can hear the original AM radio pretty well, because there is only a little wind noise to contend with. People drive by, look, smile, and take pictures with their cell phones. In a convertible you are not isolated in a hermetically sealed cocoon.

It was one of the most pleasant days of my life, though I paid for it dearly for the next few days. You see, I am fair-skinned and balding, and I made that 400-mile run down Pacific Coast Highway with the top down and no hat. After that sojourn my complexion tended toward magenta and my scalp was blistered. My lips were chapped unmercifully as well. I learned the hard way that convertibles are wonderful for cruising, but not so great for long distance high-speed travel with out sunblock, lip balm and a hat.

When recovered from my unfortunate lack of common sense, I took closer inventory of my purchase. There was no rust and the undercarriage and chassis had been cleaned and painted. The paintwork looked good, but had aged a bit, and the passenger side rear fender had been dent repaired, albeit marginally. Someone had put a back seat in it that was not original (It came from the factory with folding jump seats in back) and the mud pans that go beside the engine were gone, as was the shroud that went in front of, and under, the radiator to funnel air.

I had spotted most of this when I bought the car, so it was not a rude awakening. I had restored three Packards from this era before, and none of them had retained the pans that went down low beside the engine to keep mud and rain out. In each case, I had to have them fabricated at a sheet metal shop.

I also had to replace the big thermostat in the radiator and its link that opened the vanes in the grille. The overdrive was missing its kick down switch as well, making me think that the Borg Warner system my have been installed later, perhaps by the restorer. None of these things were particularly daunting, but they reminded me afresh that it is best to buy an original car unless it is one that has been restored by a qualified, scrupulous professional.

I knew when I purchased the car that I was buying a nice, rust free driver, so the things that needed attention did not upset me. I got what I wanted, and that was a late ’30s Packard convertible coupe like the ones my father had worked on and painted for Dutch Darrin’s shop before World War II. And I knew I could not afford one of the hand-built senior models of the time. Thankfully, Packard decided to offer models for the middle classes during the 1930s.

This happened because the great Depression, beginning in 1929, essentially meant the end of the custom carriage trade, and gradually wiped out such eminent luxury carmakers as Peerless, Pierce, Marmon and Duesenberg. Packard, the top of the heap when it came to high-end cars, was also hurting as of 1932.

That year they tried to compensate by building a smaller car called the Light Eight. It was quite handsome, and it sold well, but it was still built by hand, and resulted in more losses because it cost a lot to build, but sold for a lower price and ended up eating into the profits from the larger more regal models. At that point, Packard’s management astutely bet all their chips on marketing a mass-produced offering to staunch the flow of red ink.

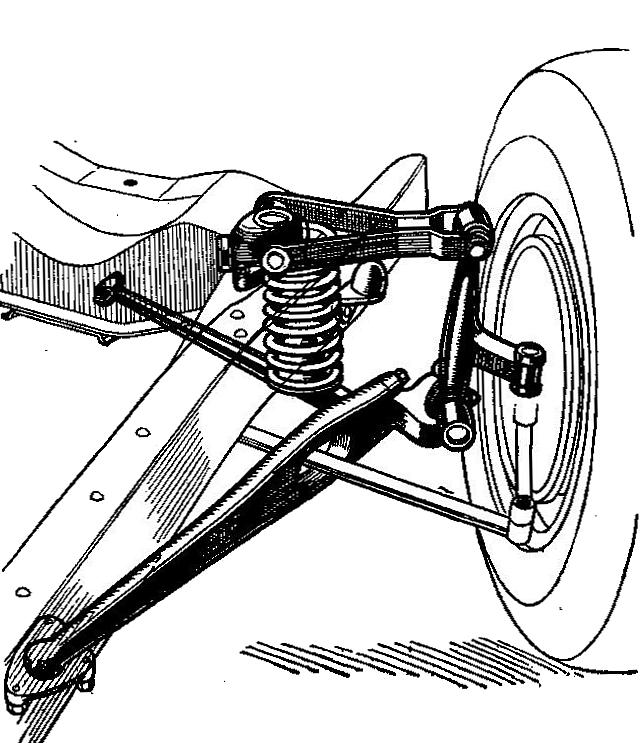

The result was the mass-produced 120, which shared the same styling cues as the senior cars, but was smaller, and built on an assembly line rather than being hand built by craftsmen. However, it was every inch the Packard of its price range. It sported a new, patented Saf-T-flex independent suspension that was later copied by Rolls-Royce, and it had hydraulic brakes – even though the senior cars still came with mechanicals.

The new, mid-priced offering had a 120-inch wheelbase, hence its name, and it came with a smooth running 257 cubic inch inline-eight and it sold like nickel hamburgers. And then, in 1936, the company bumped the engine displacement up to 282 cubic inches and offered a more extensive range of models. In fact, the 120 sold so well that year that the company added an even humbler model called the 115 that had a 240 cubic inch, six cylinder engine, and it outsold even the 120, making 1937 Packard’s best year ever.

For the 16th series (technically Packard did not go by model year, although the 16th series did correspond to 1938) was redesigned with a longer wheelbase of 127 inches, a split windshield and a sleeker more contemporary body, but used essentially the same running gear as the 1937 models. The result was a handsome bigger and heavier car with a lower rear end ratio that gave decent performance, but cut the top end speed considerably. Unfortunately, the 16th series didn’t sell that well because 1938 was a recession year.

In 1939, the styling remained essentially the same, but a new optional Borg Warner overdrive was offered that made the junior series cars much nicer to drive, and allowed for a more comfortable cruising speed and higher top end. The shift lever was also moved up to the steering column for safety reasons, and the suspension was improved for better handling using a fifth transverse shock absorber. There were other refinements as well, but Packard was not in the habit of changing styling every year as was typical with other makes of the time.

In 1938, the 120 was renamed the Packard Eight and the six-cylinder model previously designated the 115 became the Packard Six. And although the 120 designation is commonly used for the 1938 offerings by Packard buffs, it disappeared for that year and the next, but was revived by the company in 1940, when the Six also became the 110 for the pre-war junior models. For 1938 and ’39, the 120 was just designated the Packard Eight, and the 115 models were designated simply as the Packard Six.

Packard Eight models were not performance cars in the sense that they could outrun everything on the road, but they were beautifully engineered. That being said, the 160 Super Eight from 1940 was the fastest production car made that year. All of the Packard engines had thin shell insert bearings and full pressure oiling; the pistons were aluminum with steel reinforcement struts inside; and the crankshafts were massive. The 120 (Eight in 1938-’39) also came with Packard’s patented vibration damper that accounted for its legendary smoothness.

Packard’s transmissions had high quality bearings, and were so rugged that they were often used in hot rods years later. The drivelines were the open Hotchkiss type and were tough and easy to maintain, unlike the Buicks that were their competition. The Buicks, Chevrolets and Fords of the time used torque tubes with only one enclosed front universal joint. That setup had its virtues when it came to spring wrap up and universal joint lubrication, but it was much more difficult to work on.

As for Packard styling, it was always intentionally conservative, and its distinctive grille design was intended to echo the English perpendicular gothic trefoil church window. It was sort of a counter to Rolls-Royce’s Greek Parthenon radiator treatment. In the ’50s it got squashed into something that looked like a bottom dwelling fish’s mouth, but in the ’30s and ’40s that tall trefoil grille’s symbolism was unmistakable.

Perhaps the most glamorous Packards of the period were those restyled by Howard “Dutch” Darrin. He took mostly 120 models and sectioned the bodies, reshaped the doors to include the “Darrin dip”, and added a speedboat windshield and a custom dash. At first Darrin did these cars on his own for movie stars and Argentine playboys, but they became so popular that Packard offered them in their catalogs. Today, a Packard Darrin in good nick will set you back a cool quarter of a million, so I must content myself with a standard convertible coupe.

Since that sublime day over a decade ago my wife and I have enjoyed many drives down the California coast with the top down on the way to our favorite restaurant, but now we wear hats and slap on plenty of sunblock before disembarking. The old Packard loafs along silently, and people pull alongside to gawk and give us the thumbs up. The convertible coupe is big and comfortable, and makes me wish that the Packard Motor Company still existed and still built such magic carpet machines.

PACKARD 120 SPECIFICATIONS

| Base price | $1,200 |

| Production | 17,647 |

| Body Maker | Packard |

| No. Doors | 2 |

| Passengers | 2 |

| Model Number | 120 |

| Weight | 3,490-lbs |

| Wheelbase | 127 inches |

| Length | 200.75 inches |

| Front Tread | 59 inches |

| Rear Tread | 60 inches |

| Engine Type | Straight 8 L-head |

| Displacement | 282 cu. in. |

| Cylinders | 8 |

| Bore & Stroke | 3 1/4 & 4 1/4 inches |

| Compression Ratio- | 6.41 to 1 |

| Brake horsepower | 120@3600 |

| Rated Horsepower | 33.8 |

| Torque | 225 @ 1800 RPM |

| Main Bearings | 5 |

| Valve Lifters | Mechanical |

| Block Material | Nickel Iron |

| Engine Numbers | B300001 to B319537 |

| Engine No. Location | On left side of block, upper rear. |

| Lubrication | Pressure to all bearings excluding wrist pin |

| Carburetor | Dual downdraft Stromberg |

| Transmission | Standard three-speed,

Borg Warner Econo-Drive overdrive optional |

| Clutch Type | Single plate |

| Differential | Hypoid, 4.36 standard, 4.54 with overdrive |

| Suspension Front

Suspension Rear |

Independent coil

Semi-elliptic leaf, solid axle |