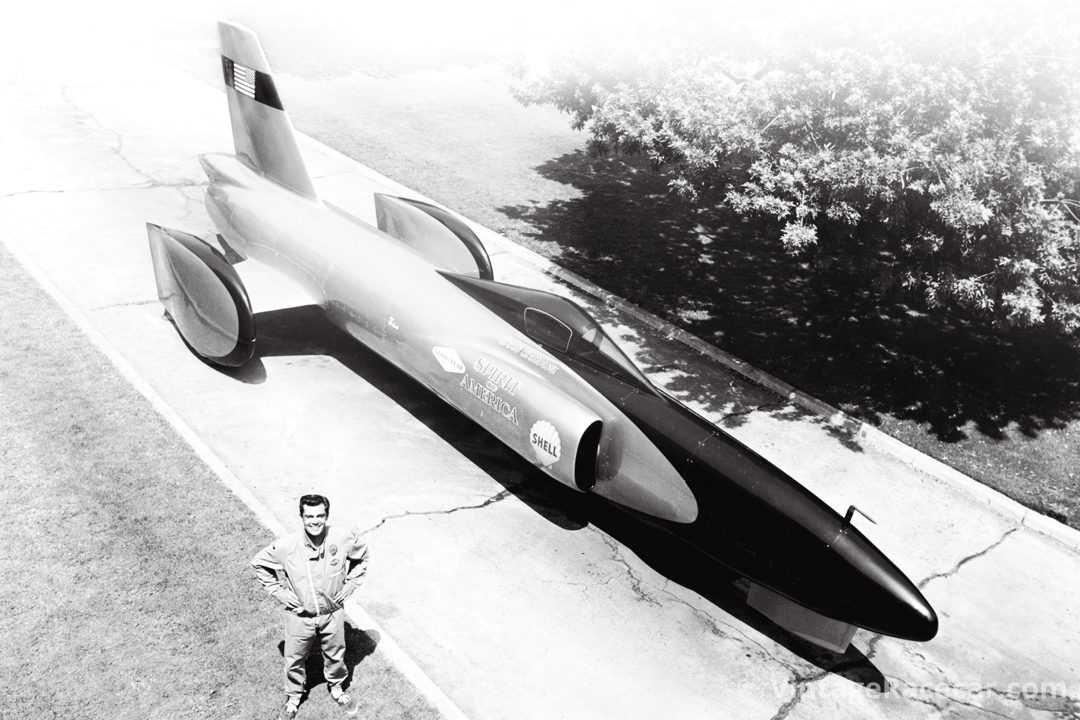

With the prospect of landing a man on the moon, the American public was captivated by all things “jet-powered” in the 1960s. So, it’s perhaps little wonder that when a California hot rodder named Craig Breedlove set the World Land Speed Record in his jet-powered Spirit of America, he quickly became an overnight American hero. Breedlove went on to become the first man to break 400, 500 and 600 mph on land, carving an unrivalled position for himself in motorsport history. However, while many would be content, Breedlove returned 30 years later(!) with a new rocket car to try and become the first man to break the speed of sound on land. While, he was beaten to this historic record by Andy Green and the British Thrust SSC team, he still harbors aspirations to become the first man to break the 800 mph barrier. Recently, Breedlove stopped by the VRJ offices to talk with Editor Casey Annis about his remarkable career and the demons that still drive him to be the fastest man on earth.

How did you get your start in racing?

Breedlove: I grew up in the Second World War era…I was just emerging from grammar school at the end of the war. They didn’t manufacture cars in Detroit between 1941 and 1946 so there was a 5-year absence of new cars and everybody had made their clunkers do. As soon as there were new cars available, there was a waiting list to get a new car. But for young guys, it was a boon because there were all these old cars on the market. That really fueled the hot rod phenomenon in Southern California, and then of course, it spread across the country. It just so happened that I was 12 or 13 when racing really took off and I just got caught up in it. Then I went to Bonneville shortly after WWII when that started up.

You went to Bonneville before being an actual participant?

Breedlove: Yeah, with some of these older guys. In fact, we took a ’29 roadster up with two flathead engines in it; one super charged in the front, and there were 3/8 by 3/8 on carburetors in the back with its drive shift like a V16. I got to drive a dragster when I was 14, as it turns out, one day when things weren’t going well my friend Bill says, “OK it’s your turn. Hop in.” You know…I was hooked—hanging out with these older guys in a car club and reading Hot Rod Magazine like a bible every month. I had talked my parents into letting me have a ’34 Ford for my 13th birthday on the promise that I would not drive it. So they let me do it and by the time I was 16 I had it built into a machine to go to the lakes with. I ended up setting a timing association record with that car.

And so where did it progress from there?

Breedlove: I got married right out of high school and had three kids by the time I was 21. Anyway, we found this Lakester that we bought. I finally got a job in the fire department in Costa Mesa. And I was pouring concrete slabs on my days off to make ends meet. That was during the era that Mickey Thompson was trying for the unlimited record with his Challenger. I was basically looking for some avenue out of my financial dilemma and working two jobs. I really didn’t have any education, and the only thing that I knew how to do was get involved in performance cars. I’d worked at Quincy Automotive on hot rods in Santa Monica and I also had worked for Bill Murphy Buick at the time Sam Hanks was there. Sam was my boss and he won the Indy 500 while I was working there.

It seems that during that period you could either be a hot-rodder or a road racer. You obviously went the hot rod route. Any specific reasons why?

Breedlove: I couldn’t afford to go sports car racing! Running a hot rod is a different story, you know. To go out and run at Palm Springs and those places where the guys were racing sport cars, that was really a league for Bill Murphy who owned a car agency. He had the money.

Was that something you had an interest in and would like to have done?

Breedlove: Oh, yeah. I would have loved to have driven road races in a sport car. But it just wasn’t in the cards. Frankly, I was looking for some way that I could participate in motor sports and had worked at material and process engineering with Douglas and been very involved with model airplanes and I had somewhat of an aircraft background. Then a surplus J47 jet engine hit the market place from the Korean War era and I begged Ed Perkins to please give me enough money to buy one of these engines to work on. We’d finagled the guy down to 500 bucks for a J47 engine.

At what point in time does one wake up in the morning and say, “I know, I’m gonna take a jet engine, strap it to my ass and go to Bonneville.” What I mean to say is, this was a major paradigm shift in the technology used for land speed record attempts, what led you down this particular path?

Breedlove: Well, I used to go down and drool over the Allison V12s and stuff, thinking maybe I could put something together like Cobb had. All of the race guys used to frequent surplus stores to pick up goodies for the racecars. That’s where the belly tanks came from to run at Bonneville. You would find some aircraft steering wheel and build a car around it. I found the engine and of course that led to the Sonic 1 car. Having that engine…that was a huge component of my plans for a car and I didn’t have to upgrade it. At that time, it was more expensive to build four V8s with superchargers like Mickey Thompson did. I just felt like this was manna from heaven.

So, in essence, you were blazing new trails.

Breedlove: Campbell had set the water speed record with the Bluebird boat with a jet engine, so there was some previous track record of this thing happening. It was sanctioned in the boats. The FIA insisted that an automobile, to set an unlimited record, must deliver 60% of the engine’s horsepower through the wheels or the motive power. I think Campbell had spent £5.7 million for that project and then he crashed at Bonneville. I was able to get Rod Chappell, who was based in Orange County, to help me with wind tunneling our car. Rod’s company, Task Corporation, had built wind tunneling instrumentation for the Naval post graduate school up in Monterey, California, and we used the wind tunnel up there. We tested fairly extensively using exposed wheels versus wheels that had fairings over them. In the model testing, where we didn’t have wheels that would spin, which would create more turbulence and more drag, we determined that on Spirit of America, by taking the fairings off and using a disk wheel in the back, we had a 30.5 percent increase in overall drag.

Anyway, in the process of doing all this I contacted Goodyear because they had built Mickey Thompson’s tires and they sent an engineer out to California based on my letters and requests. Walter Denny came out and was here for three days and at the time I had the engine, the tubing, and I had cleaned up a shop at Ed Perkin’s place near La Brea. Walt looked at all the plans and the models and he recommended that Goodyear provide tires for us. So with Goodyear’s blessing, then Ed, my machine company guy, stepped up and said ‘I’ll toss in ten grand’.

So, you really hadn’t had any outside financing up to that point?

Breedlove: No, so I quit my job at the Fire Department because I had ten grand—which seemed like all the money in the world—a jet engine and a shop to build it in. I moved back to Los Angeles and got started and then Goodyear notified me that they weren’t going to build the tires. Then Ed Perkins had kind of a business reversal in his company and he had an opportunity to rent out the shop, which I had fixed up for him. He felt really bad so he gave me the jet engine and the tubing to kind of make up for all my work. In the end, I convinced my Dad to let me use his garage, which I extended to work in. I had written to the FIA and told them that I would like to build a jet propelled, four wheel car basically, and they declined to sanction it, they said that it had to have 60% of the power through the wheels . So just on a lark, I thought I would contact the FIM [the motorcycle equivalent of the FIA]. I wrote to them and I asked if I build this jet land speed vehicle with three wheels, which would come under their jurisdiction, would they sanction it internationally? They said they already had a category for special vehicles, essentially side cars, and that I had to carry 40 kilos of ballast for the side car rider! But as long as it had the 40 kilos of ballast and three wheels, I was home free.

So really it was a sidecar record more than a motorcycle record?

Breedlove: Yes, but the main thing was that I had international sanctioning. At that point in time, the FIA was just intractable about this wheel driven thing. So when we set the record with the car in ’63, we broke Cobb’s record with it and made Campbell’s efforts obsolete and we ushered in the jet age. That was when I really started understanding that the answer to going fast was reducing drag and that it had little to do with power. The FIM, for the first time in their history, found themselves the sanctioning body for the unlimited speed record and so they invited me to the FIM congress in London. They gave me a gold medal, 24 carat gold and it was only the second one that had ever been awarded in the history of the organization.

Then you had your legendary crash?

Breedlove: Yeah, I took it over 500 mph with a very small engine by comparison to what we were competing against. That J47 in the first car was actually capable of going faster than Art Arfon’s car. But, we crashed it and that didn’t happen.

The chutes deployed too soon and burned through the cords?

Breedlove: We were pioneering a lot of stuff. No one had really built chutes to go that fast, especially at low altitude where the air’s so dense. What happened on the 500 mile an hour record was that the salt was very rough and the car had really taken a lot of pounding and on the return run, I broke a suspension bolt in the front on that three-wheel configuration. It was one of the vertical struts that controls wheel camber and it allowed the front wheel to camber over. I found that I could steer into the cambered wheel and still maintain control and I just barely made it. I had to back out of the engine once in the mile to try and regain control over the steering because it started to pull real hard. I came out of the mile at 560 and I was really anxious to get it shut down because I knew I had a broken something. I didn’t know what it was at the time. So once I got through the mile, I got the engine shut down and put the chutes on right away. I punched the button and basically I didn’t feel anything because when the chute did open, it just tore off and then once the chute door was gone, that compartment is open and the back up emergency chute was literally sucked out. It came out almost simultaneously with the main chute. I lost both of them and that’s why it went into the water. There was some construction going on and there was a wood construction bridge over a dike. I went over the bridge and then I started to turn and I ended up hitting that embankment that forms the dike for the evaporation ponds for the salt.

The car climbed the side of the levy and just as it shot over the top, the outrigger tipped it and it rolled level and went flying. I could see I was going into the water and we had four pin latches that held the canopy in and I thought I better get the canopy open! I got the canopy open and the air just took it out of my hands—it was no big deal. I slid my hands under the harness and just held my stomach.[pullquote]”…PULLQUOTE GOES HERE”[/pullquote]

You had a lot of time in the air to be doing all that?

Breedlove: Yeah, I skipped once like a stone and it didn’t grab the first time and then the second time it hit the water just like that [Breedlove makes a nose down motion]and then it just nosed over in that big ditch. I just swam over to the side, it was almost comical. I looked at the damn thing sitting there with the tail fixed in the water.

Supposedly, in an interview back in the ’70s, they said that as your crew came back to pick you up, you made a comment like “and now for my next trick, I’ll set myself on fire!”

Breedlove: Well, we had been poking fun at Arfons and his crew but then I was the one who crashed so I kind of turned the joke on myself.

What was your relationship like with Arfons?

Breedlove: Art’s a really good guy, and he’s really easy going. Certainly, we were both doing the same thing, and we were definitely competitors. There was a lot at stake in performing for either Goodyear or Firestone especially because of the money and sponsorship involved. The tire wars were going on right at that point in time. So we were very competitive but yet, at the same time, we got along really good.

The tire war really had a profound influence on land speed record attempts during that period.

Breedlove: The land speed record has always been very cost-effective as far as the amount of publicity that comes out of it. The other thing is that it’s a very unique endeavor—it’s very historic. In fact, we are sitting here doing an interview now on something that happened in 1963! We’re talking about the sponsors and they’re going to get mentioned. How many racing programs really keep generating publicity like that? Right now, the United States has not had the unlimited speed record for 21 years. Richard Noble set it in 1983 and we’ve not been able to get it back from England, but if I can get a sponsor for this car, we’ll run it in 2005 and that’ll be 22 years. Andy Green was the first through the sound barrier and that was a big accomplishment. But now its been several years . I know my new car will go 800 mph and that will be another big milestone.

Is 1000 miles an hour the next major hurdle?

Breedlove: Of course 1000 has a really strong ring to it. It really depends on the sponsor and the marketing and how it’s used and what’s done with it. I mean the car is a phenomenon and to set a record over 800, to make it the fastest car in the world, would make it a unique attraction. The Smithsonian has requested that we put my car in there as soon as it has accomplished the record. But whether we see 1000 mph in my lifetime, I don’t know.

Was your speed attempts in Shelby’s Daytona Cobra back then part of the shenanigans of tying up the salt so you have space for record runs while others couldn’t?

Breedlove: Exactly. There’s a weather window that’s suitable for running at Bonneville and its essentially early fall. I set the 600 mph record on November 15 and I was running with rain coming down. Once you get into November its totally dicey.

The Cobra run wasn’t supposed to be serious yet you set 22 or 23 records. Is it true that very little was done to prepare the car for Bonneville?

Breedlove: Bobby Tatro first ran the Cobra without the spoilers. He was the first one to take a jaunt in the thing and he spun it out in both directions at about 125. You just couldn’t run it at top speed without the spoiler. It just wanted to come around on you and you’d spend all your time flipping out to one side, feather the throttle and getting it back to hook up again and then bringing it back. I ran faster than Bobby, maybe I went 160. I said, “This thing is just really, really loose.” We were trying it out in a straight line and I was skeptical because it had pretty evil handling. After we put the spoiler back on, it was absolutely unbelievable. I mean it was a whole different car. It was a real lesson in just how important aerodynamics are. On the straightaway I ran 189 mph with it.

After having done 500 miles an hour in Sonic did that seem like just a job or was it still fun to go out and set records at those lower speeds?

Breedlove: To get it completely sideways at 160 was just fun—sliding all around. It’s all relative. The big land speed records are almost a little unreal; they’re so fast. I never got used to going that fast; it was always a big sweat every time. Now to run 600, you gotta pay attention.

You had your period of time where you were breaking those “big” records in the ’60s and then again with the new car 30 years later. Has your perception of the speed changed?

Breedlove: I get a little more intense than when I was younger. Certainly, you’ve got to control fantasies of disaster because you can defeat yourself mentally. You build the car; you engineer the car and put it together, certainly you’re not ignorant of the physical realities of what you’re doing. You’re sitting in a plastic capsule in front of this machine, and let’s face it, you can’t fly a Lear Jet into a mountain and expect to walk away from it. Certainly, things go awry at 800 miles an hour. You don’t have a big chance to walk away from it because it’s just the physical reality of what you’re undertaking. So, yeah, you have a lot of respect for the machine and you really have to stay on top of it and everything has to be right.

What is it about this project that drives you?

Breedlove: In the beginning, I remember a line from an old Steve McQueen movie, “It seemed like a good idea at the time.” Frankly, England held the record for quite a while and no one seemed to be doing much and I was sort of bored I guess, but it’s hard to work on a project that’s very, very intense and that occupies your total thought process.

So, today is it the unfinished business or is it still that raw desire to go out there and drive?

Breedlove: At this point, I’ve got 10 years work in the car and between my money and the sponsor’s money, we’ve probably spent 10 million bucks on it. I feel the thing is 95% there, it’s just we need to get the funding and get it out and run it. The data from the recorder on the car, it’s an absolute fact; you just look at it. The acceleration curve at 675 is straight up. It hasn’t begun to hit its drag rise yet. There’s a slight bow in the curve which is to be expected but based on the data we have, it looks like terminal velocity would be somewhere out there about 920 or 925 mph.

What is it that you think you need to make another attempt at it?

Breedlove: Well, last time we were hopelessly under-funded but I think we’re looking at between 3.5 to 4 million dollars to return the land speed record to America. Of course, you have to get the record too. It’s not cost effective if you don’t get the record. At this point in time I really feel we’re close.

Have you set in your mind when you might stop…at least behind the wheel?

Breedlove: Yeah, I well could have reached that point now, I mean, I’m 67 and I think my ego feels like I could drive the car but the thing is I don’t know. I certainly don’t want to be a detriment to the project’s success. Obviously, we started out to bring the record back to America, whether I drive the car or I sit out there and run it as a crew chief or a team owner. I think generally the perception is a 67-year-old guy’s got no business racing across the desert in an 800 mile-an-hour jet car. I certainly can go along with that perception. There’s any number of guys that could do it, I mean, there’s no antenna sticking out of my head so there are probably guys who could do it a lot better than I could. For me, it’s really not an issue. I have to say there’s a part of me that still wants to go out and do it. There’s so much that goes into a project like this. There’s so much work, so much effort and my major fulfillment will be to see that car do what its been designed to do and see it basically prove the concept that it was built from and see that concept work and basically win out and be the better mouse trap which is certainly more of a motivation to me than sitting in the seat.