It came as something of a surprise to me when I realized that the military has played a very large role in the postwar development of motorsport. I know it sounds like a bizarre statement, yet history seems to bear it out.

The catalyst for this revelation came to me recently, when my family and I traveled south to San Diego, California, to take in the Coronado Speed Festival, put on by Steve Earle’s General Racing, Ltd. This event, now in its 10th year, is a full historic race meeting held on San Diego’s Coronado Island at the U.S. Navy’s North Island Air Station. Once a year, the Navy closes down its runways, moves around some K-rail, and lets hundreds of historic racecars and thousands of interested spectators hold a full weekend of race meetings, smack in the middle of the naval air force’s headquarters for the Pacific Fleet.

Editor

This year, as I watched my two young daughters climb all over several Navy aircraft placed in the paddock for the public to explore—Ah, sweetee…please don’t press that red button…—I was struck by how truly amazing it is that the Navy not only allows this to happen, but also really supports it! This got me to thinking about whether this event was some type of historical aberration, but when you look across postwar racing history, the answer really is no.

As early as 1950, sports car races were being staged on military installations all around the U.S. Just in Southern California alone, there were races at the Navy’s Santa Ana Blimp base (June 1950), Reeve’s Field/Terminal Island (1953) and March Air Force Base (1953). Of course, elsewhere in the U.S. there were races all the way from Sebring (aka Hendricks Field) in Florida, to Paine Field Air Force Base in Everett, Washington, and all points in between. But where is the thread that ties the disparate pieces of the disciplined military, with us unruly racers, you might ask? One possible connection could be airplanes.

While some racing has occurred on army bases, military airstrips obviously lend themselves to being used as race circuits. However, I don’t think this is the only connection. Perhaps even more importantly is the mind-set of the men who flew the planes on those installations. One such military man was General Curtis “Bombs Away” LeMay, who in addition to being head of the Strategic Air Command, a USAF Chief of Staff, and George Wallace’s 1968 presidential running mate, was a keen sports car and road racing enthusiast. It was LeMay, and his love of road racing, that opened the door for a number of Air Force Bases like March AFB, in Riverside, California, to be used for racing. I suppose, one could argue that it was a natural marriage of kindred spirits when “fighter jockeys” and racers began to mix.

But perhaps even more supportive of this notion is the fact that this was not a uniquely American phenomenon. In the UK, Royal Air Force bases at places like Thruxton and Silverstone saw road racing shortly after the war and went on to eventually become well-known permanent racing facilities. The same was true in Australia, where events like the Australian Grand Prix, were held at Royal Air Force Bases at Caversham and Point Cook.

Another famous example was the British RAF base at Westhampnett, which in 1941, saw two bored racers-turned-pilots named Tony Gaze and Dickie Stoop, holding impromptu races on the airfields’ service roads. According to Gaze, “When the perimeter track was finished, I looked at it one morning and said, ‘I think it’s time we christened this thing.’ Anyway, Dickie and I got into our MGs and went batting around, anti-clockwise as it happened.” Gaze went on to recall that, just after the war, he ran into Lord Freddie March and some members of the Junior Car Club (JCC) at a London car showroom. During conversation, it was mentioned that Lord March, as president of the JCC, was looking for a racing venue to replace Brooklands. Gaze’s response was “Don’t be bloody silly, he owns one! You’ve got an airfield. When are we going to have a sports car race at Westhampnett?” March’s startled response was “Bless my soul…what will the neighbors say?!” Thus was born the Goodwood motor racing circuit.

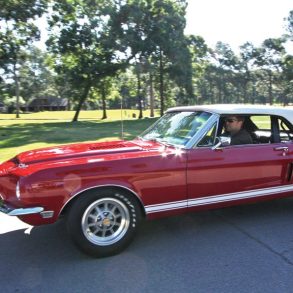

So, in the end, maybe it is the close bond between racing and flying that has coaxed the military into letting us use their facilities for so many years. Sitting in the paddock at Coronado, it’s the only reason I can think of why a guy who flies a billion-dollar, state-of-the-art fighter would leave his bird on the tarmac to run over and drool over a Shelby GT350.