1936 De Soto Airflow

The story of De Soto begins with a record for first year sales that stood for just over 30 years. It ends when Chrysler Corporation undercut its sales with a lower-priced Chrysler Newport and killed the brand. In between, it’s an amazing tale of ups and downs, good decisions and bad, innovative design and poor design choices. At its most innovative, De Soto had a car that included design features that are common on all of today’s cars. Sadly, this innovative and, in my opinion, beautiful design was too different for the American public.

De Soto

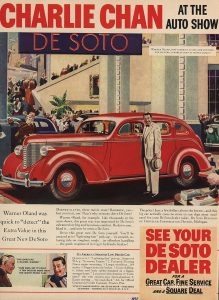

Chrysler Corporation came to be out of Maxwell-Chalmers in 1925, when Walter P. Chrysler decided to create automobiles that bore his name. It was 1928, and that would prove to be a banner year for Chrysler. In a matter of months, three brands were added to the Chrysler Corporation lineup. On July 7, Plymouth was created as a new low-priced model. Then July 31 brought the purchase of the Dodge Brothers from Dillon, Read and Company. On August 4, De Soto was introduced as a brand above Plymouth and Dodge. It made Chrysler Corporation only the second American automobile company, along with General Motors, with a full line of models.

Named for Hernando De Soto, governor of Cuba and the discoverer, in 1541, of the Mississippi River, the De Soto Motor Corporation was created in May 1928. Walter P. Chrysler’s reputation was such that 500 dealers signed up to sell the cars before they even saw them. By January of 1929, there were 1500 dealers on board. During the first 12 months of production, 81,065 De Soto cars were sold, a record for first-year sales that was held until broken in 1960 by the Ford Falcon.

De Soto was created to compete against the mid-priced cars of manufacturers like Oldsmobile, Mercury, Studebaker and Hudson, as well as those sold by the Dodge Brothers. Chrysler had tried to buy Dodge in 1926, but he was turned down. A month after creating De Soto Motor Corporation, he got a great deal on Dodge and its extensive facilities. It was too good to pass up, so he found himself with two brands in the same price range. Had he been able to buy Dodge in 1926, De Soto would probably never have existed.

The purchase of Dodge presented a dilemma —how to market such similar cars. Chrysler had become part of the “Big Three” and the only manufacturer other than GM with a potential full line of cars. Initially, De Soto and Plymouth shared many components. The biggest difference was that Plymouth would use a four-cylinder engine, while De Soto had an inline-six. In a short-lived effort to distinguish De Soto from Plymouth and Dodge, an eight-cylinder Model CF was added in 1930. Advertisements proclaimed it as the “World’s Lowest Priced Straight 8!” But the big engines in De Sotos were not the solution Chrysler was seeking, and they were discontinued, in 1931, when the last Model CF was built. De Soto would stick with six-cylinder engines until the 1950s, when the V8s returned.

During the Depression years, Chrysler’s budget brand, Plymouth, continued to sell well. In order to bolster its other dealers, Plymouth was added to all Chrysler, De Soto and Dodge dealers. It was meant to be helpful, but it certainly increased the competition among dealers. Chrysler, the corporation, needed to make its several lines more distinctive so it could better compete with other manufacturers, as well as with each other internally. Chrysler had a very strong reputation for engineering, primarily because of three talented engineers. Owen Skelton, Fred Zeder and Carl Breer were known as “The Three Musketeers” and were responsible for designing many of the innovative features such as four-wheel hydraulic brakes, downdraft carburetors and rubber engine mounting (floating power), that set Chrysler products apart from others. In house, De Soto got a new look. The cars would have distinctive new grilles with horizontal bars and a slanting windshield. Ads said, “Be Prepared to be Stared At.” The cars were stunners, but more was yet to come.

Airflow

When the Model SD was announced in 1933, De Soto became more closely aligned with the Chrysler brand and was priced above Dodge in the hierarchy. The next year, that alignment was intensified with the release of the first Airflows. This was the first foray into aerodynamics for the Three Musketeers, and it led to their greatest engineering success and most spectacular sales disaster. There was a difference, though, between the Airflows. The only model in the De Soto line was the Airflow, while Chrysler had the Airflow and other more conventional models. In his article on De Soto in Automobile Quarterly (“De Soto: Walter Chrysler’s Stepchild,” Volume XX, Number 1), Jeffery I. Godshall reported that, “Streamlining has arrived with a vengeance. Styling was pure Art Deco applied to motor vehicles, the effect as bizarre as the stainless steel spire, eagles, and winged radiator caps which adorned the Chrysler Building in New York.”

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

The design of the Airflow was courageous. It was different in so many ways. The car had the engine between the front wheels, allowing the passengers to be moved 20 inches forward of the rear wheels. Passengers were placed between the axles instead of over them. With 55 percent of the car’s weight on the front wheels, ride was improved. The car came in four forms: a six-window, four-door sedan; four window, four-door Town Sedan; two-door Brougham; and a two-door coupe. All were fastback designs. These features should have had people coming in droves to the dealerships to see and test these new cars, but exterior styling of the front of the car caused them pause. The exterior design was an early attempt to make the air flow more smoothly over the front of the car. The grille was smoothly curved vertically, headlights were set in the body next to the grille and the windshield was split and angled to give better flow past it. In 1976, Paul Wilson wrote in Chrome Dreams about the Airflow’s styling, saying that it “had some of the same grotesque anonymity as a human face covered by a nylon stocking. The Airflow had a lumbering, stupid look, a rhinoceros ugliness which automatically consigned it to the outer darkness of motordom.” Sadly, Wilson was correct in his suggestion that the car was perceived as ugly. The public disliked this innovative automobile design. De Soto production in 1934 (at 13,940) was only a sixth of that of 1929.

Chrysler saw the front end as the problem. The car had a short hood, waterfall grille and dumpy-looking fenders. Their solution was to elongate the hood and give the car a more acceptable vertical grille. It didn’t help. The Airflow had been rejected by the public and that rejection continued even after the front was redesigned. Had the Airflow been successful, smaller versions of the car were planned for Dodge and Plymouth. But the effort by Chrysler to change automotive design fizzled, and the Airflow was gone after 1937. It is likely that the decision to add the Airstream to the De Soto lineup in 1935 hadn’t helped. The Airstream was a much more conventional design. Based on a new Dodge model, with which it shared parts, it was a handsome car, but it certainly added nails to the coffin of the Airflow.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

Chassis Number 5091286

It was recently reported in the automotive news that FIVA (Federation Internationales des Vehicules Anciens) had made it pretty clear that they are not fans of over-restored historic automobiles. They believe that over-restoration takes away some of the historic elements of an automobile. They caution that “restoration should follow the principle of interfering ‘as much as necessary and as little as possible.’” It is a breath of fresh air, therefore, to have an opportunity to spend time with a survivor—an unrestored automobile that operates as it did when it was born and has acquired a much-deserved patina that only enhances its beauty. Such is the 1936 De Soto Airflow S2 owned by Larry Zamzok.

Zamzok is an Airflow fan. He likes the Airflow’s Art Deco look, and he found that he liked the Airflow people too. He heard about an available ’37, but the owner wanted too much money for it. That got him interested in finding another. He eventually found and bought a 1936 Chrysler Imperial Airflow and is having it restored. As the restoration progressed, a car friend called and asked Zamzok if he’d be interested in a De Soto Airflow that was located in town. The owner had died, and the relatives weren’t interested in the car. That began a negotiation that dragged on long enough for one of the immediate relatives to pass away, leaving Zamzok dealing with yet another generation. Ultimately, the De Soto was his. He had it towed to a shop where all the fluids and belts were changed and an electric fuel pump and radial tires were installed—the only non-Airflow parts on the car. When it was started, it ran well, and it continues to run well.

The De Soto isn’t driven a lot; Zamzok has several other classic cars and motorcycles, so it was a treat to ride with Zamzok to Petroglyph National Monument, where we would do the photo shoot. On the way, we chatted about the car and about Airflows. The cars didn’t fit in well when they were new, and they don’t fit well in the car club scene today—too many people, even car people, don’t know what they are. Airflow owners are maturing—meaning they’re getting pretty gray—and are a pretty savvy group when it comes to their cars. There is reward in being among people with a similar “sickness,” and that is where Zamzok prefers to take his car.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

As we rode, Zamzok pointed out a few of the interesting details Chrysler built into the car. Possibly the coolest is the thought that went into the ventilation. The windshield cranks open on each side independently, and there are separate pop-up vents on each side. Technologically, the overdrive is very interesting. To engage the overdrive, the car has to be in third gear and going around 40 mph. With a lift off the gas pedal, the transmission engages the overdrive. When the car’s speed drops below about 25 mph, the overdrive automatically goes off. It can also be terminated by downshifting, but in many cases that is not necessary. No buttons, no switches, no extra gear—cool.

The car is a survivor. Its original brown paint has some patina, but it still shines in the New Mexico sun. The interior is original, as well; the seats are still comfortable and supportive with plenty of legroom front and back. But it is the details that are striking and so incredibly Art Deco. De Soto Airflow grilles are much prettier than those of its Chrysler siblings. Chrysler grilles are devoid of detail, but the De Soto has chevrons added to its waterfall grille, a nice touch. Moving down the side of the car, there are wonderful Deco-styled air vents on the side of the engine compartment, very streamlined door handles sitting close together because of the suicide rear doors, and a great stylized Deco wing coming out of the attachment for the rear wheel skirts. Early Airflows did not have a trunk, but trunks were added to the later cars and were possibly the modification to the bodywork that most interrupted the flowing lines of the car. Inside, all the knobs, gauges, and even the glovebox door were great examples of the automotive artwork of the times.

Photo: J. Michael Hemsley

Driving Impressions

After the photo shoot, Zamzok was called away, so I was not able to drive the Airflow that day, and I was off to Colorado the next day. So, I asked a friend, car enthusiast, author and master model builder, David H. Allin to arrange to drive the car and report his impressions. Here is Allin’s report:

The front seat, although upright, is plush and comfortable, and wide enough for the owner, his dog and me, without crowding. After adjusting the seat by pulling up on a T-shaped release on the side, I began the starting process. First, of course, I turned the key to the “on” position, and then reached across to the choke, a knob on the right side of the dash next to the glove box. After ensuring the car is in neutral, I next pushed the starter button, located on the far left side of the dash next to the door post. With a little pumping of the gas pedal, the car started up easily. The gear shift comes up through the floor, far forward under the dash and curves out to a comfortable position on a very long shaft. The pattern is a fairly standard H, with reverse up and to the left, and the throw to second is long but not excessive. Although there is no synchromesh, the car shifted gears easily, and when the speed exceeds 40 mph, one can shift into overdrive by simply lifting off the gas for a moment until you hear a gentle clunk.

The car rode very smoothly, and took speed bumps with aplomb. The steering wheel is a normal size and even without power steering I had no problem turning the car, even at low speeds. The steering was very responsive, with little play. As you would expect of a car from the ’30s, it has unassisted drum brakes all around, and it requires planning and leg strength to bring it to a stop, but no more so than any other car of that era. I found the car easy to drive and was almost immediately comfortable with it. Despite the relatively small windows, outward vision is very good, even to the rear.

We took the car onto the interstate, but climbing a long hill with the overdrive engaged taxed the engine somewhat, and disengaging the overdrive requires downshifting. On a downhill stretch, however, we easily achieved 65 mph, and it was stable and smooth at that speed. As the owner suggested, I wouldn’t mind driving this car across country, because it felt like a very good freeway cruiser. While it doesn’t have air-conditioning, the DeSoto has large cowl vents that bring in a great deal of air, and if that isn’t enough, the two windshields can be cranked open several inches at the bottom to bring in even more air. Wind noise, even with the windows and vents open, was minimal, presumably a result of the car’s streamlined shape. There were also no rattles or body shakes, and the chassis felt very controlled. All in all, it was a very pleasant car to drive, and it reminded me of the 1950 Plymouth I owned in high school, albeit more solid and luxurious. The Chrysler Corporation was clearly ahead of its time with the Airflow design, and it wasn’t until the ’50s that all cars were that good.

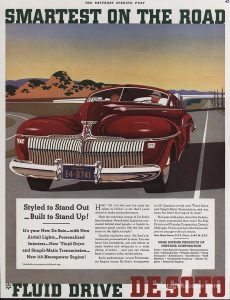

Demise of De Soto

On the cusp of World War II, De Soto produced what was possibly its second most memorable model, in 1942. It was the second car produced by an American manufacturer to have pop-up headlights. Unlike the Cord, which used lights hand-cranked into position, the De Soto’s “Airfoil” lights were powered. The car was sleek, but it was also big, which became a defining characteristic of Chrysler products, as well as those of many other American auto companies after WWII. De Soto continued to be competitive in the marketplace into the 1950s. In 1955, they gained Virgil Exner’s “Forward Look,” and a De Soto served as the Indianapolis pace car in 1956. All seemed well until the economic downturn in 1958. The recession, sometimes called the Eisenhower Recession, affected mid-priced cars in particular, including Ford’s new Edsel. For De Soto, 1958 sales were 60 percent lower than 1957, and the problems continued to get worse through 1960. Forty-seven days after the 1961 De Sotos were introduced, the marque was killed on November 30, 1960. Sadly for De Soto dealers, Chrysler kept shipping them 1961 De Sotos through December, leaving them with inventory that was very difficult to sell. De Soto, once a proud and innovative marque, was tossed on the trash heap of automotive history.

Epilogue

In doing the research for this article, I gathered a number of quotes from other sources. Most of them, as can be seen above, were not very complimentary. Godshall began his Automobile Quarterly article with a short paragraph that synopsized the history of De Soto and was hard on the Airflow:

“It burst on the automotive scene with a brilliant light, setting a first-year sales record that would endure for three decades. Then it faded quickly almost to oblivion with a radical, streamlined car practically laughed off the market. It revived only to become a stepchild fated to use hand-me-down bodies from its larger brothers for the rest of its life. Its death came suddenly in middle age. Such was the roller coaster life of the De Soto, a car that never quite fulfilled the promise of its beginnings in 1928.”

Not a bad synopsis, and he was right about the Airflow. It just was too advanced for the American public. Nothing Chrysler could do saved it, but I doubt that it was as serious a factor in the demise of De Soto as Godshall suggests. Personally, I think the Airflows, both De Soto and Chrysler, are beautiful. I particularly like the first cars with their waterfall grilles and fastback styling, but I go to jelly when I see anything that is of the Art Deco style —cars, planes, trains, trucks, furniture, posters —really, I mean anything. There was an Airflow on Craig’s List near me recently. It was in terrible shape—nearly no floor, interior shot, who knows about the engine. I wrote the number down and put it next to my computer for a couple weeks. I kept looking at it and trying to decide whether to go see it. Thankfully, my problem was resolved when the ad disappeared, suggesting that it had been sold. So, my sincere thanks to Larry Zamzok for sharing his car with me and to my friend, David Allin, for helping me with this article.

SPECIFICATIONS

Body & Chassis: Bridge-truss frame with semi-unitized body featuring integral space-frame and all-steel body

Body style: Four-door, six-passenger sedan

Drive: Front engine, rear drive

Engine: Inline 6, flathead

Displacement: 3957 cc, 241.5 cu in.

Bore/Stroke: 3.3 in, 85mm/ 4.5 in, 114mm

Carburetion: Ball & Ball Model E6Gl 1-barrel

Power: 100 hp (73.6 kw) @ 3400 rpm

Torque: 185 lbs-ft (251 nm) @ 1200 rpm

Transmission: 3-speed synchromesh manual with overdrive

Suspension: Front – Tubular, one-piece axle; longitudinal semi-elliptic leaf springs; hydraulic lever shocks; Rear – Solid axle; semi-elliptic leaf springs; hydraulic lever shocks

Brakes: Hydraulic; 11×2 inch steel drums

Wheelbase: 115.5 inches, 2934 millimeters

Overall length: 197 inches

Overall width: 71 inches

Overall height: 66.5 inches

Front track: 57 inches

Rear track: 56.25 inches

Weight: 3,378 pounds

Wheels: 16×4.5 stamped steel discs

Tires: 16×6.50

Click here to order either the printed version of this issue or a pdf download of the print version.