At the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, much of the world quietly celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Armistice that ended “The War to End All Wars.” Total casualties, killed and wounded, numbered about 37 million. Of that number, approximately 17 million were killed – 7 million civilians and 10 million military personnel. Sadly, the agreement to end that war included provisions that ultimately led to the Second World War. There were plenty of stories of heroism and devotion to duty during the war, and one of those belongs to Edward Vernon Rickenbacker, America’s “Ace of Aces,” race driver, savior of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, leader of Eastern Airlines, and Vice President of Rickenbacker Motor Company.

Eddie Rickenbacker

The man we know as Edward Vernon Rickenbacker was actually born Edward Rickenbacher on October 8, 1890. His parents were German-speaking, Swiss immigrants. As a child, Eddie was a bit of a rascal and somewhat accident prone. He was hit by a streetcar when he was four, fell down a well, scarred his chin when he fell from a tree, and had to be rescued by his brother when he got his foot stuck in a railroad track. He was also a risk-taker. Together with his buddies, the self-named Horsehead Gang, they went to a gravel pit where they pushed a rail wagon up a hill so they could ride it back down. Eddie somehow fell and was run over by the wagon, which cut his leg to the bone. It was one of the injuries that he would disguise for the rest of his life.

Eddie Rickenbacker was far more than a risk-taking rapscallion. He was an achiever; someone who overcame the obstacles put in his life path. John F. Ross, in is biography “Enduring Courage – Ace Pilot Eddie Rickenbacker and the Dawn of the Age of Speed,” explained Rickenbacker well: “Ultimately, Rickenbacker’s story boils down to courage. Not the kind of courage that comes in a blinding rush . . . but one that is trained to purpose and gets stronger, wiser, and more effective with experience.”

The first test of his courage came in 1904. He was a 13-year-old seventh-grader when his sometimes violent father, William, started a fight that he lost. After weeks in a coma, William Rickenbacher died, leaving his wife Lizzie with seven children to feed and clothe. Eddie’s response was to quit school, lie about his age and grade level and go to work at the Federal Glass Factory. Despite having three older siblings, Eddie assumed the role of the head of the family.

One year later, in 1905, Eddie saw a crowd gathering and pushed his way through to see what the attraction was. A salesman was showing off a 10 horsepower Ford Model C. Eddie was intrigued. When the salesman saw him, he must have thought it would make an impression on the crowd if he took the kid for a ride. Eddie climbed aboard, and off they went. Eddie was completely seduced by automobiles by the end of the ride.

Hoping for a better salary than at the glass factory, Eddie went to work for the Pennsylvania Railroad cleaning rail cars. His curiosity and energy earned him a place working in the machine shop, where he did mostly menial jobs but earned the respect of the older workers. He good-naturedly took the jokes and teasing by the older men, and they taught him about using a lathe. He worked there until a wheel came off a cart loaded with lumber, spilling the wood and trapping Eddie against his lathe. Another deep cut to his leg put him to bed for several days, but boredom got him up and out of the house to hobble the streets of Columbus.

A shop he saw on his walks, Evans Garage, intrigued him, so he decided to try to get hired there. Their business had been bicycles but had recently begun to service automobiles. Eddie had seen the automobiles stored inside and wanted to be a part of that industry. William Evans was operating the garage alone, so when Eddie approached him, Evans had to admit that he could use some help. He offered Eddie 1/3rdthe salary that he had been making at the railroad, and Eddie accepted. Eddie was very curious about the automobiles, so he took time to study them. Eventually, when Evans was gone, he would start the various cars, taking a Packard for a ride inside the shop. He even dared to take one of the cars and pick up his mother and some friends for a ride once when Evans was gone. To his credit, he overcame some problems he encountered with the cars – a seized piston on the Packard and a dead battery on an electric – and was never caught. It is likely, though, that Evans suspected Eddie’s offenses and chose to ignore them. During his time at Evans Garage, Eddie was encouraged by a former teacher to sign up for a correspondence course in automotive engineering. Once able to understand the drawings, he quickly improved his knowledge of how automobiles worked.

Eddie had been making small steps toward his future. The next job change was a giant step. He had seen the activity at the Oscar Lear Automobile Company, where automobiles were built from scratch – every part except for the tires. Eddie started hanging around when he was off work. Lee Frayer, a partner in the business, asked what Eddie wanted – a job was the answer, but it was not offered. Eddie decided to impress Frayer and went to the shop at 7:00 am the next day. He did a thorough cleaning of the garage floor and work surfaces but left one section untouched for comparison. Frayer arrived, saw what had been done, and hired Eddie. Frayer became like a father to Eddie, a father who wasn’t violent or frequently lost his temper. Eddie was given tasks to assist one of the skilled workers, but he quickly showed his initiative and creativity. Seeing this and watching Eddie study his correspondence course during lunch, Frayer made Eddie an apprentice at a higher salary. Eddie was soon learning how to use the machinery and build automotive assemblies. It wasn’t long before Eddie was offered a place in the engineering department. One of the department’s tasks was to design a Frayer-Miller for the 1906 Vanderbilt Cup race. Eddie had shown a talent for diagnosing problems with engines, so Frayer asked him to be his “mechanician” for the race. Much later, when asked, Eddie commented: “Put simply, engines have always talked to me.” It was his first trip away from home, and his first racing experience; he was hooked. It didn’t matter that the car broke during the qualifying runs and never raced, Eddie was going to go racing.

Another bit of serendipity helped Eddie with his future when he was dispatched to help Clinton Firestone, who had broken down in his car. Frayer had been hired by Firestone to design and build an automobile for Firestone’s business, the Columbus Buggy Company in 1909. He brought Eddie with him. When Frayer received word that Firestone had car trouble, he sent Eddie. Eddie arrived, diagnosed the problem, fixed the car and had Firestone back on his way. Firestone said little to Eddie, but when he got back to town, he asked Frayer who that kid was who fixed his car. Eddie went racing in the new Frayer-designed car, a Firestone-Columbus at a track in Iowa, although not very successfully. He learned a good lesson at that race, and he applied the knowledge at subsequent races in the Midwest and started winning. His experiences included besting Barney Oldfield in a 100-mile race at the Columbus Driving Park. Both cars broke, but Eddie had outdueled Oldfield, a feat that Oldfield graciously acknowledged.

Eddie was first employed as chief tester and engineer at the Columbus Buggy Company, but Firestone soon put him in charge of sales in the north-central district. It wasn’t a job he liked. Worse, while looking out his window at a passing train, a hot cinder got in Eddie’s eye, eliminating 30% of his peripheral vision in that eye. It was an injury he had to work hard to overcome, and one he kept secret from later employers, especially the U.S. Army.

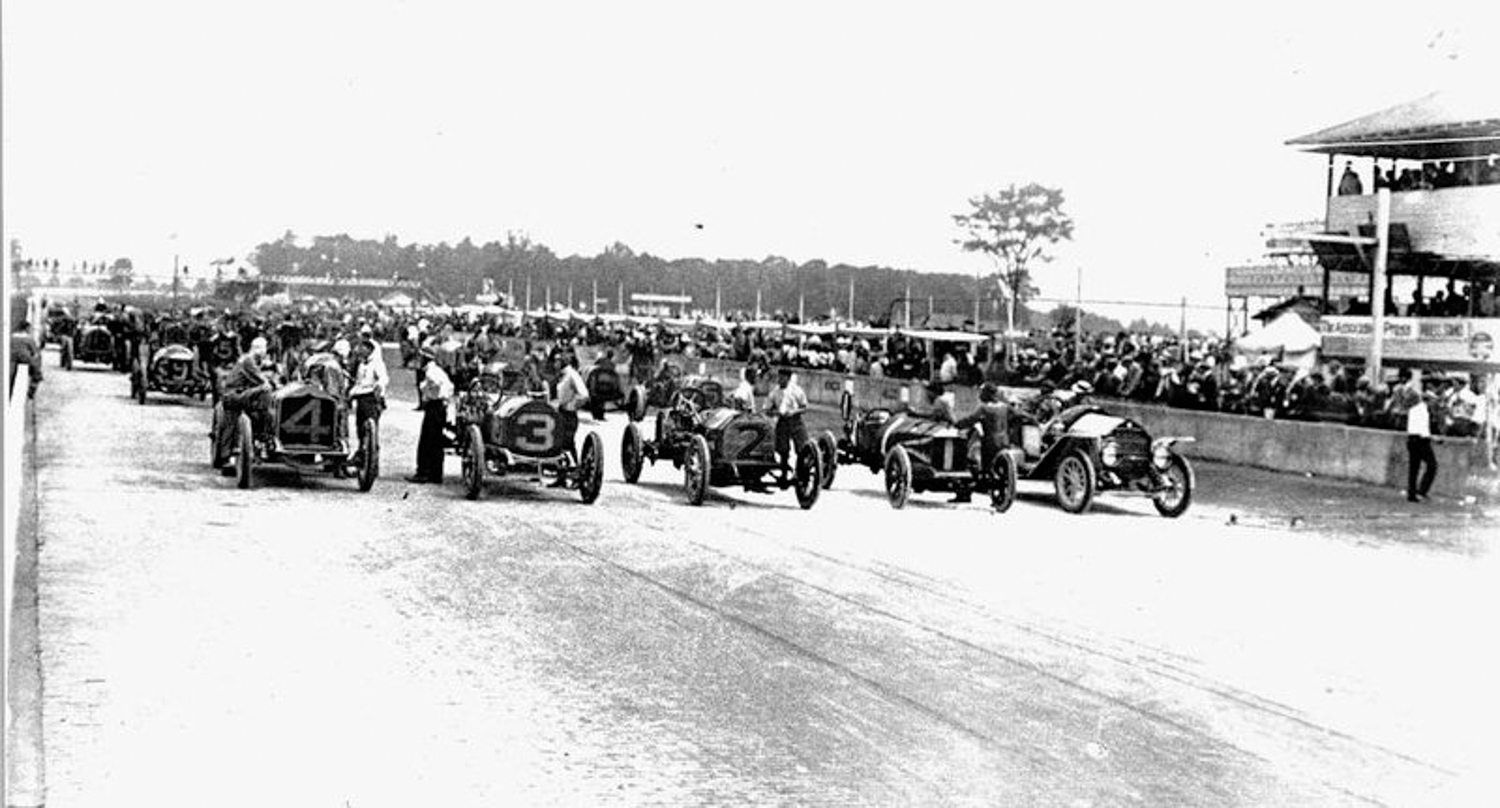

Indianapolis, Indiana, was looking for a way to attract tourists to their city in 1911. They decided on having a 500-mile race at its speedway. Frayer entered with Eddie as again as his mechanician. They started 26thand finished 13th having completed 197 laps of the 2.5 mile course. That race convinced Eddie to become a full-time racing driver. He joined a traveling race group, ironically called the “Flying Squadron,” that toured the U.S. He drove a Duesenberg with some good results and eventually got his own race team sponsored by the Prest-O-Lite Battery Company. He subsequently raced first in Peugeots, then Maxwells. His race record during this time is difficult to ascertain until he began racing in the AAA/USAC Champ Car Series. In that series, from 1913 through 1916, he raced in 41 races, won 7 of them, had 16 top five and 24 top ten finishes, and one pole. One innovation he introduced to his pit crew was a time-and-motion study of his team’s pit stops. He orchestrated his pit crew so that they could perform a stop faster than any other team, and he had them practice their stops so they would perform perfectly during the race.

During this time, as hostility grew toward German speaking people, Eddie changed the spelling of his name from Rickenbacher to the more American-sounding Rickenbacker, and he added “Vernon” as his middle name. Changing the spelling of his name didn’t help when he went to England, in 1916, to evaluate the suitability of Sunbeam’s racecar for America racing. He was arrested by British police and interrogated, thought to be a German spy. Finally, Sunbeam executives secured his release. But the English arranged for him to be followed while he was in England. The Sunbeam looked like it would make a decent racecar, but it was unlikely that the company could supply cars at a time when materials were being dedicated to war production. Eddie learned a lot about what was going on in the war and was impressed with what he learned about aerial combat and the units that had been organized for the war, like the Lafayette Escadrille, which was made up of American pilots fighting for the French.

Captain Eddie the Warrior

Eddie had two encounters with aviation during his racing days. The first was in California where he met Glenn L. Martin, founder of the aircraft company that bore his name. Martin gave Eddie his first plane ride – important because it showed Eddie that his fear of heights was only a bother on the ground and not in an airplane. Even more important to Eddie’s future was a chance encounter with a downed plane in a field. Major Townsend F. Dodd of the Army’s Signal Corps had experienced engine trouble and had landed in the field. Eddie stopped, diagnosed the problem, and had Major Dodd back in the air quickly. Major Dodd was to be an important friend after the U.S. went to war.

When war was declared by the U.S., Eddie thought that the Army would benefit from having pilots who had been racing drivers and mechanics. They would understand how the engines worked and should be very successful as pilots. Unfortunately, leaders of the Signal Corps dismissed the idea because the drivers and mechanics weren’t college educated. Pilots would be sought from West Point and from colleges, especially the Ivy League schools.

An American expeditionary force was sent to Europe to evaluate the needs for American forces. It was led by General John J. (Black Jack) Pershing. Someone suggested that the general might benefit from having a racecar driver as his driver while in Europe, and Eddie got the job. He enlisted in the Army, as a Private, but quickly learned that being a Private was not pleasant. He had heard that Major Dodd was on the same ship carrying the Americans to Europe and sought him out. Major Dodd, never having forgotten Eddie, pulled some strings and got him promoted to Sergeant. A much improved situation.

Eddie was well known to French racing drivers, many of whom had raced in the U.S. Their familiarity with him gave him additional credibility among the American leadership. During the evaluation trip, Eddie drove for General Pershing, Lieutenant Colonel Billy Mitchell, and Major Dodd—very good connections to have for an aspiring fighter pilot. He also renewed his acquaintance with James E. Miller, a New York banker who was now in charge of training for the Americans forces in France. Knowing Eddie’s abilities, Miller asked him to get the training base established. Eddie agreed but only if he was allowed to go to flight school. He was successful in setting up the facility in Issoudun, France, and was allowed to go to flight school. Eddie had a problem with landing because of his eye injury, but he overcame it by practicing over and over until he was able to land without any problems. He passed flight school and was promoted to First Lieutenant. Unknown to those who allowed him to attend, he was past the cut-off age of 25 – he was 27 but lied about his age to get in.

After flight school, he was back in Issoudun managing the facility. In order to fly in combat, he needed gunnery school, but the base commander felt he was too valuable to spare. In order to prove that the base could operate without him, he feigned illness and was sent to bed for weeks. The base operated fine without him, so he was allowed to attend gunnery school. Once again, he had to compensate for his bad eye, but he was successful. Finally, he would be a combat pilot.

Marshall Foch, the commander of the French forces, wanted the Americans to be under his command. General Pershing resisted those attempts, and the Americans remained independent of the French. LT Rickenbacker was assigned to the 94th Aero Squadron of the 1st Pursuit Group. The other Squadron in the Group was the 95th. There would be quite a contest between the two Squadrons to see which was the most successful. The 95th got a head start when they were supplied with planes before the 94th.

Even with the emphasis on wartime production in the U.S., there was no time to develop a competent fighter plane for the U.S. forces. Instead, they were given the French Nieuport 28, a plane the French pilots were reluctant to fly. Once they had their planes, the 94thneeded an insignia. It was decided to use a top hat. A member of the Squadron from Texas suggested that when a man in Texas was willing to fight he threw his hat in the ring. So “Hat in the Ring” was adopted as the insignia for the 94th Aero Squadron.

It wasn’t easy for Eddie. The other pilots were nearly all Ivy League men, and they looked down on Eddie because he had little education and was rough spoken. But Eddie gradually won them over with his knowledge of the engines and planes and because of his daring. In an early flight in a Nieuport, he experienced a near fatal problem with that plane – the wing cloth could shred, exposing the structure of the wing during harsh maneuvers. As his plane hurtled toward the ground, Eddie tried desperate actions and finally got the plane under control again. He passed what he had learned on to the other pilots.

To help with their training, Major Gervais Raoul Lufbery, a pilot from the Lafayette Escadrille, was assigned to the 94th. He trained the pilots in the techniques of aerial combat espoused by Oswald Boelke, a German pilot who appeared to be destined to be Germany’s top ace until he was killed a few years into the war. The Red Baron, Baron Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen, earned that title with 80 kills before he was killed himself. Lufbery took to Eddie and became his mentor.

The French method for tallying kills was adopted by the American forces. Every pilot involved in a kill would receive full credit. To be named an “Ace” took five kills. Eddie showed his daring early on. He notched up several kills and was in a race with pilots like LT Douglas Campbell and LT Frank Luke, Jr. for the first title as an Ace. But Eddie was reckless in combat, something that he reconsidered while recuperating from an ear infection in the hospital. He became determined to be less reckless and more thoughtful in combat.

His success in combat and the thoughtfulness he encouraged other pilots to adopt helped him be chosen as the Commander of the 94th Aero Squadron and got him a promotion to Captain. From then to the end of his life, he was affectionately known as Captain Eddie. As the new commander, Captain Eddie went on his first patrol alone. By this time, the Nieuports had been replaced by the better Spad 13s – the planes the French pilots preferred. Taking his Spad high into very thin air, Captain Eddie spotted seven German planes. There were five Fokker D.VII fighters protecting two Halberstadt CL.II reconnaissance planes. Captain Eddie dove on the Germans and shot down one of the Fokkers and one of the Halberstadts. The rest of the Germans scattered. It was for this action that Captain Eddie would win the Medal of Honor for his bravery, although he had to wait until 1930 to receive it.

Nearing the end of the war, the 94th was tasked with shooting down the German Drachens – observation balloons. This was a particularly dangerous mission, since the Germans sited antiaircraft batteries around where the Drachen were tethered. Captain Eddie and LT Luke were tied for the title of “Ace of Aces,” until Luke was killed after shooting down two of the balloons. Luke survived the crash of his plane, but it was never determined if he died as a result of the bullet that hit him during the attack on the balloons, when he resisted the German infantrymen who tried to take him prisoner, of if he took his own life, having sworn that he’d never be taken alive.

Captain Eddie became the American Ace of Aces with 26 kills – 21 planes and 5 balloons. His decorations included French Legion of Honor, three Croix de Guerre, six Distinguished Service Crosses, and the Medal of Honor. At the end of the war, Captain Eddie was offered a promotion to Major but declined. He wanted to return to civilian life.

Captain Eddie the Businessman

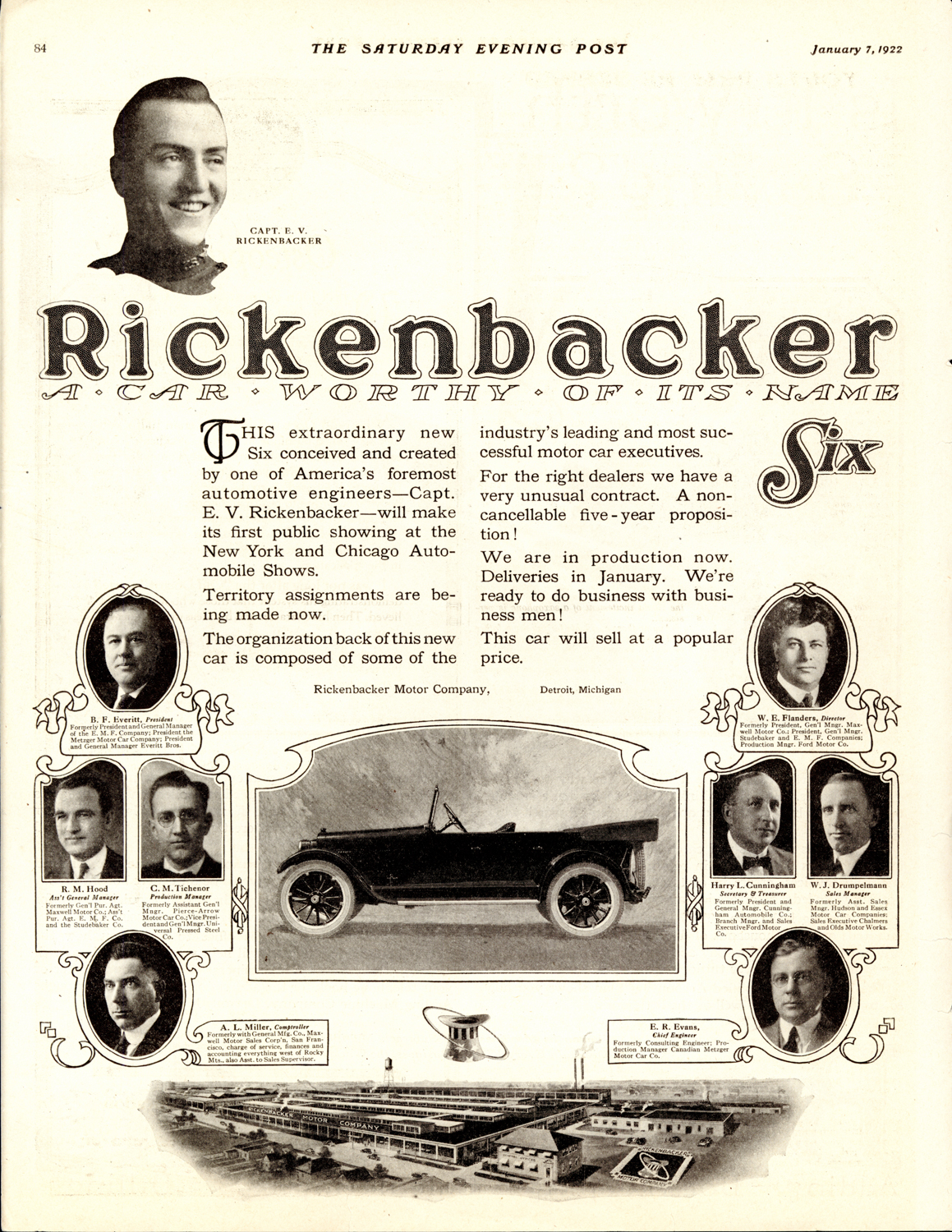

Captain Eddie was offered book and movie deals, but he was not interested. He tried lecture tours, but he wasn’t good at it. He thought about racing but appears to have decided that he’d had enough danger in his life. About that same time, Byron Forbes (Barney) Everitt was interested in getting back in the automobile business. His previous automobile company, E.M.F., had not survived, but Everitt saw opportunities in the post-war years. He understood manufacturing and was operating the second largest body building plant in Detroit…and he had a plan. He approached his former partners; William Metzger (the “M” in E.M.F.) turned him down, but he was able to convince Walter E. Flanders (the “F”) to come out of retirement.

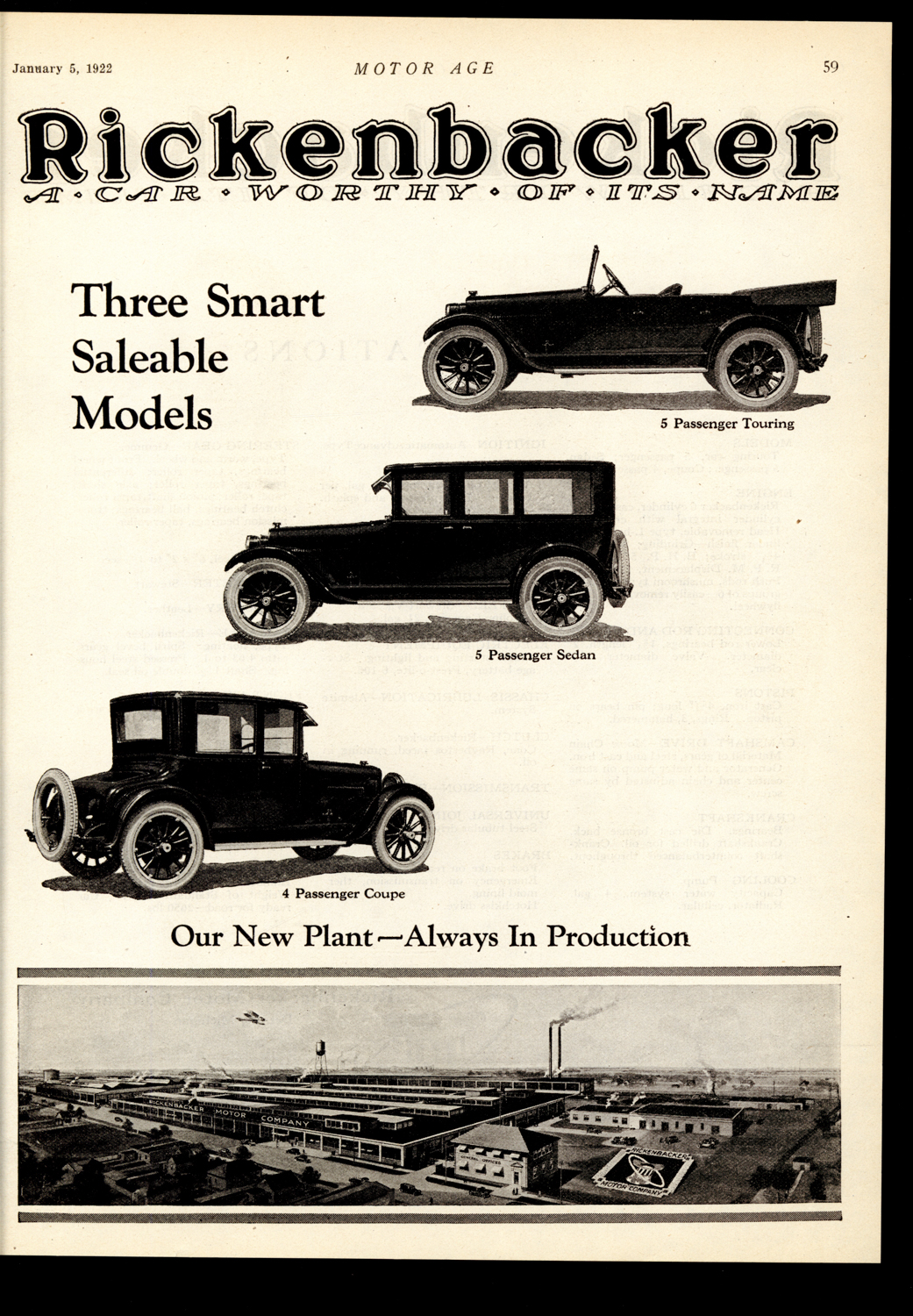

Everitt had the facilities and knowledge with which to build cars, but he needed something that would separate his automobiles from the rest. He approached Captain Eddie, who enthusiastically accepted the offer to join the company, which became the Rickenbacker Motor Company, in July 1921. Captain Eddie was named Vice President and Director of Sales. He was responsible for public relations and sales for the new company. Everitt, who is believed to be the financier of the company, bought more manufacturing space from the Detroit Pressed Steel Company. The goal was to build a medium-priced, six-cylinder car that would be just different enough to gain the interest of the car-buying public. The insignia for the car would be the same “Hat in the Ring” that had adorned Captain Eddie’s Spad, and the company slogan was “Worthy of its Name.”

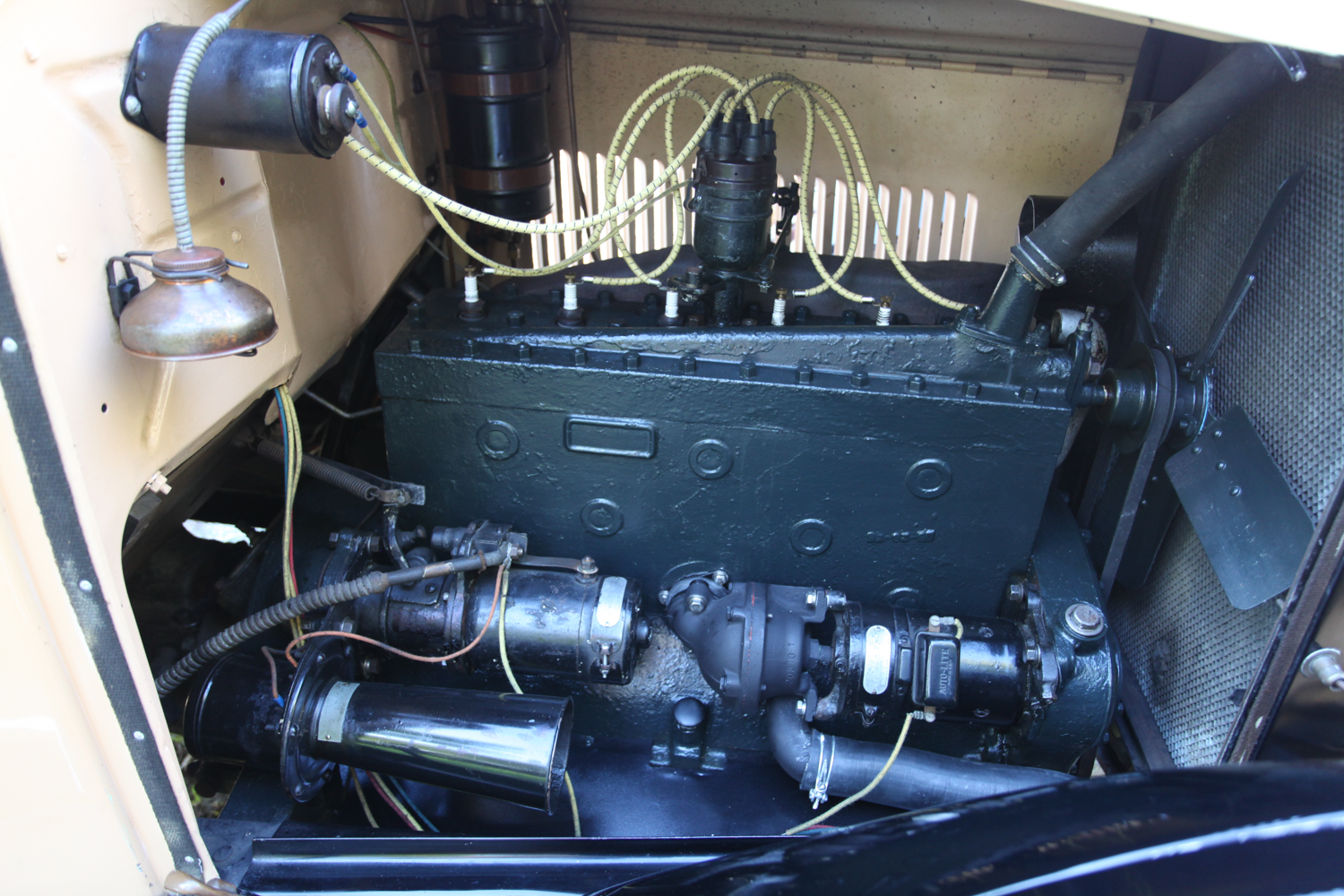

The look of the car was pretty standard for the 1920s, but there were several things that set it apart from other medium-priced cars. The engine was a three main bearing six of 218 cid producing 58 hp at 2800 rpm. Frame channels were wide and deep to give a rigid chassis to eliminate weaving. Springs were 36” semi-elliptic in the front and 56” in the rear. There were two innovations claimed by the Rickenbacker Motor Company. The first was the use of two flywheels, one on each end of the crankshaft, to dampen vibrations – the cars were guaranteed to be vibration free. Supposedly, this was an innovation that came from Captain Eddie – he had inspected a particularly maneuverable German plane he had shot down and saw how it used two flywheels. The second innovation was four-wheel brakes. It was a first for a medium-priced car. Advertising by the company for the brakes unleashed a torrent of claims from other companies that having brakes on the front wheels was dangerous. Each of those companies had many chassis on hand that were designed for rear brakes, but as soon as those chassis were out of the inventory, every company went to four-wheel brakes. Flying in the face of the claims that the brakes were dangerous were the insurance companies that offered a discount if your car had them. The company even created a bumper sticker that said, “Beware – four wheel brakes” to make their point. In her Automobile Quarterly article “Hat in the Ring – the Rickenbacker” (Volume XIII Number 4 – Fourth Quarter 1975), Beverly Rae Kimes reported, “B.F. Capwell recalls that Rickenbacker’s brakes caused no trouble, save for the drivers following behind in two wheel brake cars.”

Rickenbacker Motor Company did well for several years. In time, they became the 16th largest automobile manufacturer in the U.S. Song writer Leo Wood produced a song, “In My Rickenbacker Car,” that praised the cars lack of vibration with this line: “She won’t jar your vacation for there’s no vibration . . . in my cracker jacker Rickenbacker.”

The company added an air filter in 1923, than added “The Rectifier” the following year to prevent “crank case dilution.” Kimes described it in her article: “It was in essence a miniature distillery where all surplus gasoline, water and acids formed in the cylinder and carried by the oil were broken up into their component parts, distilled, purified and then fed back to their original sources to be used over again.” This was actually a patented device that Rickenbacker used under license.

The company introduced its first 8-cylinder automobile in June, 1924. The Vertical 8 Super-Fine had a longer wheelbase and had an L-Head engine with a nine bearing crank. It displaced 268 cid and produced 70 hp at 3000 rpm. The engine was carbureted and was fired as if it was two 4-cylinder engines. It had dual ignition, dual manifold, dual mufflers, and, of course, dual flywheels.

For the year, sales were down, and the company lost money. Everitt believed the company needed a full range of models, so he looked for merger partners. His goal was to merge with Peerless, but he also approached the Trippensee Closed Body Company in Detroit. Peerless saw no advantage to a merger and refused. Everitt acquired Trippensee, an acquisition that eventually proved to be detrimental to Rickenbacker, as Trippensee was unprofitable.

Another decision that didn’t help the company was to reduce the selling price of the Vertical 8. It was made without involving the dealers, who had purchased cars at an undiscounted wholesale price. The dealers would bear the burden of the price reduction, and they weren’t happy. In another attempt to boost sales, Everitt introduced a “heftier” six that could use the same body and many of the same parts as the Vertical 8. The car was announced in January 1925. The displacement of the Vertical 8 was also increased. To bolster public relations, Everitt hired Canon Ball Baker as “chief test pilot.” Baker was known for his coast-to-coast speed records. Something must have worked, as sales were up from the previous year. Unfortunately, they were still below what was needed for the company to be healthy.

Two things happened that must have given Everitt some hope. The first was a letter from Freelan Oscar Stanley giving muted praise to a Rickenback car he had experienced: “I am surprised as gas car can be made to so nearly approach the excellent driving qualities of the Stanley Steamer.” The other was the introduction of the Super Sport at the New York Auto Show. It was very stylish, especially compared to the other Rickenbacker autos. It was powered by a straight 8 with two carburetors producing 107 hp at 3000 rpm. It was guaranteed to do 90 mph. But it was the exterior that was most striking. The car had a torpedo-shaped rear, airfoil bumpers, cycle fenders made of brass bound, laminated mahogany with wood inlay ornaments, and bullet-shaped headlights. It was so low it needed no running boards. Instead of the winged mascot, this car got an airplane mounted atop its radiator.

The Super Sport didn’t help, and only fourteen were ever built. Everitt instituted additional price reductions, which made the dealers furious. Captain Eddie had not been able to create a strong dealer network, and the company was showing signs of an ultimate failure. In a reorganization, Captain Eddie resigned in September 1926 along with a number of others. Now there was no Rickenbacker involved with the Rickenbacker Motor Company.

The company went into receivership in November 1926, with Everitt and Security Trust Company the receivers. Three new and more stylish models were announced in December, but it was too late. In February 1927, Everitt requested permission from the court to sell the assets. Four attempts to sell the assets as a whole were unsuccessful, so the court allowed the assets to be sold separately. Possibly the most successful bidder was Jörgen Skafte Rasmussen, who bought the engines, machinery, patterns, and some tools and dies. His original plan was to build engines in Germany for a new Rickenbacker constructed in the U.S. That plan failed, so Rasmussen acquired Audi in 1928 and used the Rickenbacker engine in Audi Zwickau and Dresden models until 1932.

Captain Eddie went on to other ventures some successful, some not. One of the unsuccessful ones was a start-up airline he founded together with Anthony Fokker. One that still stands successful today is his purchase and renovation of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Captain Eddie raised $700,000 in 1927 to buy the speedway, which had fallen into disrepair. His efforts renewed the speedway and helped make it what it is today. His longest success started with his acquiring an engine company and selling engines to General Motors. That led to his holding several executive positions within the General Motors aviation businesses. He was able to assemble $3 million in 1938 for the winning bid to purchase Eastern Airlines from GM. He subsequently modernized the airline and made it a viable business. Captain Eddie stayed with the airline into the 1950s when he was made Honorary Chairman.

Even though far from most dangers, Captain Eddie faced two challenges not of his making in the 1940s. On a flight to Atlanta, the Eastern Airliner in which he was flying crashed as a result of the crew’s failure to adjust their flight speed, and therefore arrival time, to local air pressure in Atlanta where there were thunderstorms and low atmospheric pressure. He suffered broken legs and other injuries, which bothered him for the rest of his life. Before rescuers arrived, Captain Eddie took charge of the injured, making sure no additional damage was done to them.

As a vocal supporter of U.S. involvement in the conflict in Europe, he became an important campaigner for the country to support the Allies. Captain Eddie became close friends with Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. When Stimson asked him to personally deliver a rebuke to General Douglas MacArthur concerning his ill-advised criticisms of the decision to concentrate the fight in Africa first, Captain Eddie agreed to fly to New Guinea. A poorly prepared B-17 bomber left Hawaii with malfunctioning instruments resulting in the plane having to be ditched in the Pacific Ocean. During the 24 days that the crew and passengers spent in three small rafts, Captain Eddie is credited with keeping the will to live burning in all but one. Thanks to the persistence of his wife, Adelaide, the search continued well after it had been initially called off, and all but that one were saved.

Captain Eddie died of pneumonia in Switzerland on July 23, 1973. A true American hero was gone.

Rickenbacker Automobiles

During its short life, the Rickenbacker Motor Company produced a variety of body styles and three engines. Initially, they were all straight-6 engines. A larger, more powerful six was added when the Vertical 8 was introduced. Model designations were fairly easy to understand. The earliest cars carried the designation “A.” Since they were all 6-cylinders, the model was “A6” in 1922. Rickenbackers produced, in 1923, were also all 6-cylinders, and they received the designation “B6.” Similarly, the next three years used “C,” “D,” and “E” according to the year for the 6-cylinder cars. When the Vertical 8 was introduced in 1926, it received the designation “B8” rather than use an “E” model designation. For 1927, the previous model designations were abandoned, and the few models designated were the “6-70,” “8-80,” and “9-90.” The car profiled here is a 1925 6-cylinder sedan, so it is a D6. The 1926 Super Sport shown at the New York Auto Show was a B8.

Rickanbacker Motor Company provided a number of choices of body styles for their cars. They ranged from small to fairly luxurious. The smallest body styles were the two-seater Coupe and Roadster. They were quite sporty looking; a couple would look good driving around town, especially in the roadster. Larger body styles, the Sedan and Touring, accommodated more passengers, four comfortably and five on occasion. At the top end was the Brougham. At first glance, it appeared much like the Sedan, but it had an oval “opera” window on each side and some fancier accoutrements.

1925 Rickenbacker D6 Sedan, Serial Number 42749

Kyle Eaton nearly grew up with the Rickenbacker D6 Sedan he now owns. His grandfather, then his father worked part-time at the Lincoln Highway Garage in York, Pennsylvania. The garage had been a Rickenbacker “distributor,” according to a business card scanned onto the Rickenbacker Automobile Club of America website. Garage owner Lynn Haines owned the car and used it for short in-town trips, and Eaton’s father sometimes took young Kyle to the garage while he was working. Eaton was very familiar with this particular car and decided he would like to own it someday. When Haines retired and sold the garage in 2004, he offered the car to Eaton and his father. Eaton was in college at the time and couldn’t afford to buy it, but he kept track of the car as it sold first in 2004 and again in 2007. Eaton eventually approached the last of the owners in 2013 to see if it was for sale. It was, but no agreement could be reached on the price. Eaton and his wife decided to buy the car some months later and called the owner – not for sale, he was told. Eaton told him, “Keep me in mind. If you decide to sell it, I’m more than interested.” Eaton had his Google alerts set so that any mention of a “Rickenbacker” would ping him. “I got an email alert saying the car was consigned to an auction.” The owner had ignored the request to call when he decided to sell, but Eaton won the car at auction. He paid more than he hoped but less than what the owner had wanted in 2013. Thinking about how he pursued this car, he said, “I know they say you’re not supposed to get emotionally involved with a car, but I remember seeing this one as a little kid.”

With the axle properly installed, Eaton drives the Rickenbacker anywhere, except on the interstate. He takes the car to shows and drives it if he can stay on secondary roads. The car is a good driver at 40-45 mph, but it cannot keep up on the intestate. Eaton takes his sons with him to car shows, and they play in the back of a 1925 Rickenbacker! “How many kids can say that?”

Antique cars are a family thing. Eaton’s father has a Chevelle SS that he bought when he was 18. Together they are restoring a 1930s Dodge one-ton pickup that he great grandfather bought new. The next project for Eaton will be a 1926 Chrysler he often saw sitting in a garage near his childhood home. It never moved, so one day, Eaton stopped, talked to the owner, and bought the car. It’s a complete car, but it’s also a project.

Driving Impressions

What an honor to drive a Rickenbacker! When driving any antique car, you have to try to set your mind back to when the car was new. It can be a challenge, though, since 1925 was nearly 20 years before I was born. A modern pickup truck will handle, accelerate, and stop better than any 1925 sedan, so it is imperative not to compare it to anything more recent.

First thing to do when driving a “new” car is to become familiar with the gauges, controls, and starting procedure. Gauges are simple, since there are few. Left most is the speedometer/odometer. The speedometer is a rolling gauge – no faceplate showing all the speeds and no needle; only a rolling “barrel” of numbers to show the current speed. Next on the right are the ammeter and oil pressure gauges, then a gorgeous period clock. The fuel gauge is outside the car on the fuel tank, and the temperature gauge is on top of the radiator cap, clearly visible to the driver, although it is likely wafts of steam will be what attracts the driver to an overheating issue. On the steering column are spark and gas controls, used when starting. Transmission is a standard three-speed with reverse above first – no synchromesh. The pedals are arranged as in modern cars, but there is a starter button on the floor near the gas “pedal,” which is also a button. There are also a power switch and a choke. If you need the windshield wipers, you get out of the car to turn them on. There is a knob at the top of the windshield used to raise the windshield for better air flow – 1925 air conditioning.

Starting the car from cold is relatively simple. Power switch on, choke out, spark retarded (lever on the left of the steering column), gas lever (on the right) down for more fuel flow, pump the gas pedal a couple times, and push the starter pedal on the floor. Eaton has this car tuned well, and it starts immediately.

Driving the car requires keeping a few things in mind – the location of the gas pedal compared to the starter button is one of those. It is a tall car, so the center of gravity is high – expect some body roll. It is a rare car for its time for having four wheel brakes, but they are mechanical drum brakes from nearly 100 years ago, so stops have to be planned well in advance. And the gearbox is non-synchro, so double clutching is required.

In any car of this age, one of the things you just have to do is press the horn button. How can you not smile when you are rewarded with a loud “OOOOOHHH-gah?” Eaton directed me to a nice, curvy, rural road in Pennsylvania farm country. I was impressed with the handling. For a car this tall, there was less body roll than I expected. It did fine through a 90° corner at 30-35 mph. Overall, it handles at least as well as other cars of the same decade I have driven. Hills can be a problem, though. The spacing of the gears is long, so a shift from second to third, together with the double clutch, can lose you a lot of speed. Eaton was much better at keeping the speed up when he drove his car. Just a matter of getting your shifts right. The other side of the hill can also be a problem. 1925 mechanical brakes take a while to slow a car, so it just requires planning – understand that, and you won’t have a problem driving this car. We came down several long, steep hills without issues. It was a breezy day, and with the sail area on this tall car, there was some sway as a result of cross winds. The only other problem I experienced was with the steering – it is very direct, but there is a small dead spot in the center. Steering the car straight took a bit of attention to keep it in a straight line. Once you knew about it, it was pretty easy to adapt how you reacted to the steering.

I have a lot of respect for people who restore and drive cars of this era or before. Mechanically, cars became increasingly sophisticated with time. Remember, the Rickenbacker was one of the first cars with four wheel brakes, and the first medium-priced one to have them. I have to thank Eaton for allowing me to drive his Rickenbacker. I’m sure he groaned quietly as I crunched the gears as I figured out how the car wanted to be double-clutched, but he still encouraged me to drive the car farther.

Epilogue

During the too few years of production of the Rickenbacker cars, it is estimated that something more than 35,000 cars were built and sold. The Rickenbacker Automobile Club of America actively seeks out surviving Rickenbackers, but only a hundred of so are known to exist. The website includes photographs of 40 original and restored cars and another four they call “Parts, Pieces, or In-Progress.” Hopefully, there are more out there yet to be found and, ultimately, restored. There connection with Captain Eddie is an important reminder of what this American hero accomplished during his life.

Specifications

Body 4-5 Place Sedan

Engine Inline 6-cylinder, dual flywheels, side valve, 2 valves/cylinder

Displacement 218 cid

Bore/Stroke 82.55 mm (3.25 inches)/120.65 cc (4.75 inches

Power 58 hp @ 2800 rpm

Induction 1 Stromberg carburetor

Transmission 3-speed, non-synchro

Drive Rear-wheel drive

Front Suspension 36 inch semi-elliptic springs

Rear Suspension 56 inch semi-elliptic springs

Brakes 4-wheel drum

Wheelbase 2972 mm/117 inches

Weight 1500 kg/3307 lbs

Tires 31×5.25