Kirk F. White took a circuitous route to his successful classic car business in Philadelphia, entering the workforce earlier than most young men after his father passed away when he was a pre-teen. Because he had to help keep the family afloat financially, he went to work as a gofer in a summer camp for $30 to be paid at the end of the summer! As luck would have it, his mother rented out one bedroom of their three-bedroom home to a Mr. John Jewell, who introduced Kirk to automobiles and the racing of them. Among his early haunts was the daunting Langhorne Speedway not far from his home, and eventually Kirk moved into car sales and worked his way up to owning his own dealership. Among his associates in the business was Roger Penske, who subsequently became his partner in several ventures that took him as far from home as Le Mans in France. Today, his motorsports life has slowed down a bit and its focus has turned toward collecting automobile memorabilia. VR contributing editor John R. Wright recently engaged White in conversation to discuss his life in the sport.

Despite enjoying a happy childhood, didn’t your life change completely after your father died in 1949?

White: I was devastated. Our family was destitute as my father was the main breadwinner, but my mother rose to the occasion and my sister and I survived. However, my mother had to rent out one bedroom of our three-bedroom house.

Could you give us an encapsulated version of how that happened, and how it affected your life then and in the future?

White: I was 11-years old and one day a gentleman appeared at the front door. His name was John Jewell, and it turned out he was a prince of a guy. He was one of the fellows who got me interested in cars. It was a Saturday, and for a change I didn’t have a million chores. John asked me if I would like to go to the midget auto races at Hatfield Raceway. I had only been to one race before, the first 150-mile NASCAR stock car race at Daytona. The races at Hatfield were in the evening on the Montgomery County Fairgrounds. Virtually as my feet hit the ground, my life changed forever. I’ll never forget the glorious, staccato shrieks of the exhausts of the Offies and the Ford V8-60s bellowing out over the fences. The drivers I saw were Bill Schindler—in the #2 Caruso Offy, Len Duncan, Ted Tappet, Tony Romit and a host of others. Yes, a switch turned on and I never turned it back off.

The first Christmas after your Dad’s death was also pivotal in certain ways. Can you tell us about that?

White: My sister had come home for Christmas and it seemed all the attention of the family was focused on her. I had gone out with my meager savings of $5.63 and had bought her a complete set of aluminum pots and pans. I got socks, handkerchiefs, a shirt, a sweater. But then my mother told me there was one more gift for me behind the tree. It was a Cox Thimble Drome Special, a gas engine tether-racing car! The complete set up. Bright red racing car, engine, tether setup, fuel, instructions, everything! My Dad had worked at Leeds and Northrup, and my father’s friends got together and purchased it for me. A family friend brought it over on Christmas Eve. I raced it in my basement and got pretty good at it.

Didn’t you get so good you won a championship?

White: In the late summer of 1950, I went to the Philadelphia Sportsman Show. I entered the Thimble Drome race with a car provided by the organizers. I had a technique of lying on my back to race the car and using that technique I was faster than the other entrants. The prize I won was a yellow certificate and a brand new Cox Thimble Drome Champion in brilliant yellow over red!

You also became a bicyclist, and didn’t you customize your bike as most kids do?

White: I reversed the handlebars, put streamers on the handgrips, things like that. However, the bike enabled me to get around more to see cars, garages and races.

There was one garage where you used to hang out in particular, can you tell us about that?

White: I discovered the Morano Brothers garage in Erdenheim, just five miles from home. What caught my eye as I rode past was the sight of an Offy-powered midget racecar parked just inside the front door. Morano Brothers Garage was the quintessential American automobile repair garage, run by the two Morano brothers, blustery Joe and his quiet brother, Mike. Joe ran the front of the garage with a lot of supercharged energy, too much noise and bad cigars. Mike, his older brother was tall, gray haired and quiet, an enormously accomplished mechanic. To this day, their sons run the business.

So who ran the Offy?[pullquote]

“I remember Le Mans well. I left for Paris on June 6, 1971. I had never been to Europe before, and hadn’t the foggiest notion of what to expect as an entrant.”

[/pullquote]

White: The midget racer in the Morano Brothers garage was owned by Ken Brenn and raced by the great midget driver Len Duncan. Len was proudest of the fact that Harry S. Truman had handpicked him as his personal driver during a post-war tour of Europe.

Can you go into some detail about your first visit to the Langhorne racetrack?

White: It was just outside Philadelphia. I got so hooked on it that I would hitchhike the 25 miles there and back. However, I didn’t have enough money for a ticket and so I snuck in with a family who had paid to get in. I loved that track!

Then there was your first Indy 500 in 1949, but you couldn’t go.

White: I listened to it on my tiny radio. I remember Bill Holland won that race.

Then life intervened and you grew up—maybe. How did you maintain your interest in cars?

White: I did some cars, a supercharged T-Bird, hot rods and then I went into life insurance and had a family, but I have to say I never liked selling life insurance. When I thought about it I was focusing on death all the time, in the present and then after the person died. I felt it was morbid. Then I saw in the Sunday New York Times a classified ad for a Jaguar sports car, a car I could possibly afford. That initial purchase pushed further to a dealership where I marketed Ferraris and other sports cars.

Wasn’t it then that you started to come into contact with dealers of the cars you liked?

White: I met Edgar Jurist who owned a wonderful old Packard showroom on Broadway. I met Max Hoffman who dealt in Jaguars, Volkswagens, Porsches, etc. My leanings tended toward British and Italian cars, never Porsches. Until my 1974 Carrera. Jurist had a real influence on me. I purchased a long-wheelbase California Spider for $6,400 and went home with the car. I enjoyed it a couple of years.

Around that time didn’t you come into contact with Al Garthwaite who had been at the first race at The Glen in 1948?

White: He was a Philadelphia dealer for Ferrari. He was very wealthy. He also owned Lee Tire. He had raced with the Collier Brothers and (Cameron) Argetsinger in a super 2.9-liter Ferrari. At any rate, he called me and asked me if I could drop by. He told me he wanted a sales manager for the dealership. I took the job. That’s how I got into dealing Ferraris. Also, at about the same time a friend wanted to open a dealership with me. I was caught between switches. I decided to go with my friend Grant. At this time I was interested in early competition cars. My partner wanted to sell new cars. An old ratty racecar would come in and he would tell me that it better be gone in two weeks or you’ll own it. After I worked there, I left and opened Kirk F. White Motor Cars.

Eventually you made it into the ’70s and your link up with Roger Penske, but isn’t there another story about how Brock Yates came to you about a certain Ferrari Daytona?

White: Roger’s dealership was not far from mine. I met Roger through his brother David, and about that time we were talking about the 512. Now, as for the Daytona, Brock Yates came to me asking for a loaner for the first Cannonball Run. His co-driver was supposed to be Robert Redford, but instead Dan Gurney became his driver. I figured that they wouldn’t get far, that they would be arrested by the time they got to New Jersey. They went on to win it by a bunch. I think Dan Gurney said that at no time did they exceed 175 miles an hour…

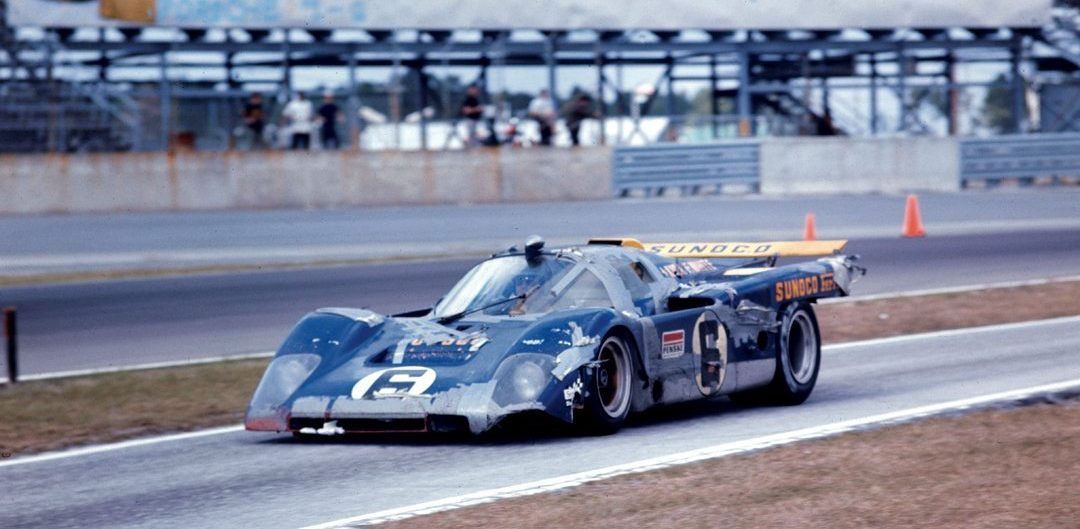

Now, can you tell us about the car that has been described as the most beautiful Ferrari 512 ever, and its role in the Le Mans saga?

White: Roger’s shop was not too far from my dealership. He dropped by our 63rd Street shop at around 7:00 on a Saturday morning in July 1970 and said to me, “Why don’t you round up a handful of your customers, investors and pals, buy a Ferrari 512, the necessary parts, a spare engine etc., and we’ll take it to Newtown Square and turn it into a real racecar? We’ll enter it in the long distance races and run for the World Championship next year. Mark (Donohue) will drive it.”

Then what?

White: It wasn’t easy to find a car as there were only 25 512s built. We found out that Ferrari 512S serial number 1040 was owned by Chris Cord and Steve Earle. Jim Adams had been driving it in the Can-Am and Doane Spencer was the crew chief. It was for sale… for $32,000.

You purchased the car, but when Roger and Mark went to Ferrari to purchase parts they got a big surprise. Can you explain?

White: Roger and Mark went to Ferrari and did buy a large inventory of parts, but Ferrari refused to give them a discount on the $28,000 worth of parts they purchased no matter how they pointed out the publicity they would receive.

So now your $32,000 investment has become $60,000.

White: Then we had Berry Plastics in California do a new body for the car in a lighter and stronger fiberglass.

Wasn’t that when some hot rodders and Indycar guys got involved?

White: Mark and Don Cox reset the suspension points and Lujie Lesovsky did the wing. Don Cox felt that new wing was absolutely necessary.

Jim Travers and Frank Coons did the engine, and didn’t you say they found it was very strongly built and well designed?

White: Traco found the engine initially tested out at 590 horsepower. One day when it was on the stand, Mark asked them what the oil pressure was set at. They told him 120 pounds. Mark thought that was too high and he reset the oil pressure relief valve 60 pounds and immediately we saw a horsepower rating of 614 horsepower. Mark said the oil pressure was so high it was shoving so much oil into the timing chest of the engine. After the oil pressure relief valve was reset there seemed to be no limit to how high the engine would rev.

Then after a lot of preparation, didn’t you set off for Le Mans?

White: I remember Le Mans well. I left for Paris on June 6, 1971. I had never been to Europe before, and hadn’t the foggiest notion of what to expect as an entrant. I met a teammate, Jerry Riegal, and tried to sort out a rental car, and somehow as well sort out the maps and the toilet facilities. Peter Reinhart, with the paperwork that had been done by Bernard Cahier, was shepherding the Sunoco Ferrari 512M through French customs. This Group 5 racing car was masquerading as a Pennsylvania-registered road vehicle to bypass the need to post a huge bond, upward of a million dollars.

Oh the joys of dealing with French bureaucracy!

White: We arrived at the track and located the building where you received your credentials, but we had to deal with the officials who dealt them out. However, Bernard Cahier had arranged everything. Then, there was a catch. A gentleman with a multitude of armbands approached us with two other men. I had met him before when he was in the company of Luigi Chinetti the U.S. distributor for Ferrari. He invited us for drinks at 5:00 that afternoon in the BP building. All the gentlemen present commented on the presentation of the car and then the other shoe dropped. The main man told us we had to use BP fuel and lubricants while racing at Le Mans and that we had to put BP decals on the Ferrari. I replied it simply could not be done as Sunoco was sponsoring the car. In reply the man said we then could not participate in the race.

Wasn’t that a shock?

White: I stood my ground. Then the man said the logos did not have to be large. Two four-inch BP stickers would do. I racked my brains and figured I could have the decals put on the thin back panel just below the wing and right above the exhaust pipes. I knew that the exhaust would roll over them and they would be invisible 50 or so miles into the race.

Can you tell us something of the other team members?

White: As a group we were there with a very tight number of team members, but we had two of the finest long-distance drivers in the world: Mark Donohue and David Hobbs. At Le Mans, Mark was also the team manager. He was totally stoked to be racing here. For Mark, a victory at Le Mans meant more to him personally than a win at Indianapolis. Fred Marik of Professionals in Motion and Judy Stropus, timer extraordinaire, had also come over with us.

Photo: Steve Robertson

You also owed Luigi Chinetti for releasing one of his entries for you, can you tell us about that?

White: Initially, in early April when we had filed our entry for Le Mans, we were promptly informed that we were too late. Fortunately, Luigi Chinetti, three-time winner at Le Mans and the United States distributor for Ferrari and patron of the North American Racing Team, released one of his Ferrari 512 entries to Penske Racing. Chinetti was one of the true sportsmen of the era. We put a small logo on the car to thank him.

Ferrari sent one supposed expert to assist you with the car, but it did not go well.

White: Ferrari had sent “a man” from Maranello to assist our team and the nine other 512s at the track…. He advised us a final drive gear ratio that for us was way too short, and our car ran out of “gear” halfway down the Mulsanne with a top speed of only 205 mph. On top of that there appeared to be four dozen Porsche 917s, and we couldn’t keep track of them all. In particular the “long tails” were clocking at least 230 mph down the Mulsanne. They had bodywork that spanned two zip codes! I also learned the Ferrari representative the factory had sent worked in the parts department at the factory. Mark and David could run anyone down anywhere on the course, but the Mulsanne is 3.5 miles long.

No one on the team was especially enamored of the neighborhood Shell station where the team made its base.

White: It was hardly a Penske Racing facility. It was very untidy and must have bothered Roger no end. People must have wondered how extraordinary our American effort really was. However, the place was awash in people, racing press, fans, friends and curious locals. However, many people were paying attention to me, much to my discomfort. I asked John Woodard, who was chief mechanic, what the fuss was about. He replied, it was me. He handed me a copy of France-Soir and there I was on the front page. The headline read: “Un Milliardaire Americain a tranforme une Ferrari por gagne au Le Mans…” and that I was utilizing the services of the engineer Penske. Mark commented that anyone who comes to practice at Le Mans in Gucci loafers with no socks deserves whatever he gets. I didn’t even have the sketchiest makings of a multi-millionaire.

Can you discuss the super engine that came courtesy of the Ferrari factory and how it came to be installed overnight?

White: Woody said Chinetti came to Roger and told him Ferrari had prepared a super engine for the 512 and the team was the recipient. He said they would give us the engine in return for the Traco-prepared engine in our car. Now Woody had to swap the Traco engine for this new engine. Why were we chosen? We don’t know whether or not Roger ever paid for the engine, by the way. Anyway, Mark went out and came back to our garage with an industrial-sized crane with a big wrecking type ball on the end, huge beyond belief. We had that engine out in no time. David Hobbs had said with typical English wit that we should have picked up the car and banged it against the wall until the engine fell out! At the end of practice there was a rattle in the upper end of part of our engine. The Factory Ferrari guy said that was nothing. He said the injector slides rattle at bit at idle. I still think about it. Why us? There were nine other cars, three other factory cars and those six represented by factory distributors. The damned engine we got from Ferrari was not worth a hoot. Woody and Mark were distressed. We were never able to practice with it. Mike Clark bought our engine—the rattly one—and it ran like a train for his 512. We never had a failure with a Traco engine.

Photos: Chuck Andersen

And how long did the engine last?

White: Our Ferrari lasted a few hours and we went out when it was still light. Clark’s car lasted into the 13th hour when someone knocked him into a sandbank.

Today, Canadian collector and vintage race driver Lawrence Stroll owns the car.

White: He comes to vintage races and drives the heck out of the car. He’s an excellent driver. He also comes to the Cavallino and Palm Beach events. I still get emails about the car.

After Le Mans didn’t you go in different directions in racing?

White: At the end of 1971, Roger and I sponsored an F1 McLaren and took 3rd at Mosport. We went to Trenton with a car and David Hobbs, but it was configured to fit Mark and he didn’t fit. However, he did come 10th. We sponsored David in the Tasman Series down under, and in 1972-’73 we distributed McLaren Can-Am cars, but Porsches ruled and we didn’t sell many.

Then, in 1972, we had a sponsorship with one of Dan Gurney’s Olsonite Eagles with Bobby Unser driving. It was not a big involvement. That year Bobby was on the pole with a new track record and led the race until a tiny ignition part let him down. Also we went to Daytona in ’72 with a Ferrari 365 GTB4. Holman and Moody did it and it got a 1st in class. Skip Scott drove the car. He was an accomplished driver, but not much of a mechanic. A piece of linkage came loose, and instead of trying to fix it he walked back to the pits and retired the car.

Would it be fair to say that by then your involvement in racing was winding down?

White: I think we did a lot of small things. We sponsored Gary Bettenhausen and did a deal for Bonneville.

Weren’t you also involved in setting up some auctions?

White: We did some auctions for three years, but that was it. I’m not a big fan of concours, as I think it’s gotten to the point where the cars are over-restored.