I’ve stumbled onto a couple Daytonas over the years, well, two and a wing, actually. First experience was in 1969 on my way to my new assignment as an ROTC instructor in eastern Washington. My wife, baby son, and I were in a Volvo 145 wagon hauling our Lotus Europa on a trailer. As we crossed the Wyoming plains, an odd automobile appeared briefly in my mirrors before it flew past me at a significant speed differential. It was the first Daytona I had ever seen in person. Second experience was as an Army captain on an emergency operation to raise the levees around Morgan City, Louisiana, in 1973. The base of operations was in the city’s materials yard. Way in the back of the yard was a wing. It had no Road Runner on it, so I assumed it was from a Daytona. The yard supervisor said I could have it, but I didn’t think I could get it home and so passed it up

Last winter, before the pandemic, I was bored one weekend and decided to attend the World of Wheels show that was in town. I’d been a couple years before and didn’t think I’d go again – just not my kind of cars. But I went, and as I was nearly done exploring, I saw a blue and white Dodge Daytona in with a group of other locally owned muscle cars. The owner’s name was on the placard, so I took a chance and Googled him. I found him, emailed him, and the result is the car featured here.

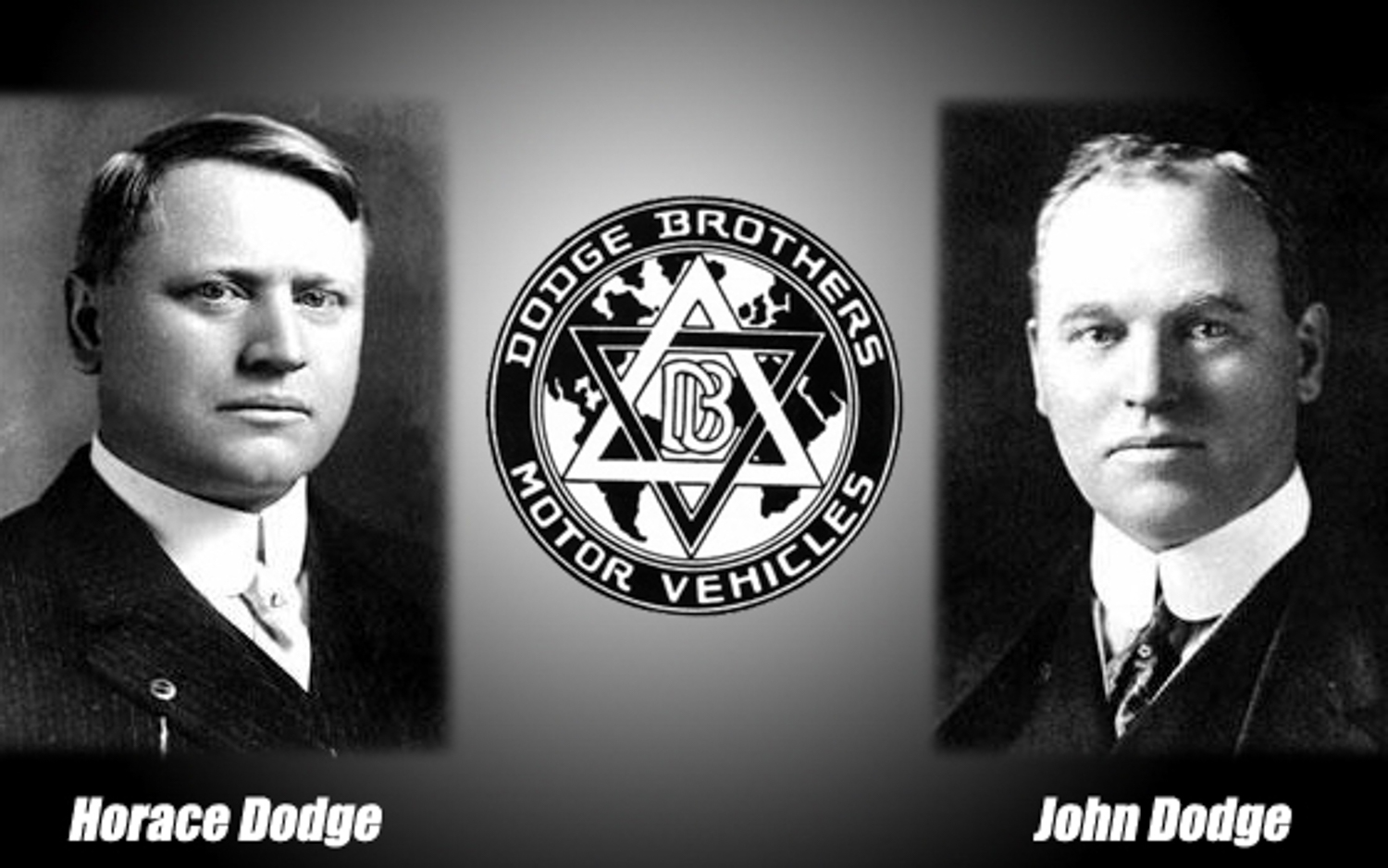

Dodge Brothers

There would never have been any Dodge Brothers automobiles if it had not been for Henry Ford. Like Ford, the Brothers were very successful in their businesses and they worked very hard to be successful. Unlike Ford, they also liked to drink and play hard.

John and Horace Dodge came from a family of machinists, so it was no surprise that they went into that kind of work. John, born in 1864, was considered a visionary, while Horace, born in 1868, was a mechanical genius. Together, they were quite a team. An early job for the brothers was with the Murphy Boiler Works in Detroit, where, depending on the reference, they primarily did rough machining or got their first taste of fine work. Around 1890, the Brothers moved across the Detroit River to Windsor, Ontario, where they worked for Canadian Typothetae Company. It was during their time there that Horace designed and patented a ball-bearing bicycle hub. The brothers, together with Harold Evans, formed Evans and Dodge Bicycles in 1897. The brothers remained with their company when it was bought by the National Cycle and Automobile Company. It was sold again in 1900 to the Canadian Cycle and Motor Company, and the brothers decided to sell their shares in the company and return to Detroit.

The brothers used the $7500 they had saved to open their own machine shop – Dodge Brothers. They produced parts for area bicycle manufacturers who were prospering during the bicycle boom of the early 20th Century. One of those bicycle companies belonged to Ransom Olds. Olds was the first to benefit from a decision to diversify from bicycle parts to the new automobile market. He contracted with the Dodge Brothers to build engines for his Curved Dash Olds beginning in 1901. When a fire destroyed much of the Olds plant, the Dodge Brothers received a contract for more than 2000 transmissions in addition to the engines they were building.

Henry Ford apparently noticed the job the Dodge Brothers were doing for Olds and approached them in 1903 to build engines, transmissions, and axles for the original Model A being produced by Malcomson & Ford. When Ford established the Ford Motor Company, the Dodge Brothers production was almost entirely for Ford. Ford, though, was not quick with payments. As a result, the Dodge Brothers received a 10% share of Ford Motor Company and wrote off some of the debt that had accrued. The brothers were among the first stock holders in Ford Motor Company, and both became directors. John Dodge became a Ford Vice President in 1906.

Dodge Brothers was very successful and they undertook an expansion of their machine shop. That expansion resulted in an entirely new factory in Hamtramck, in 1910. The relationship with Ford remained difficult. With the development of the Model B, Ford began to diversify his suppliers, with the intention of eventually bringing it all inside Ford Motor Company. Dodge Brothers now had a factory capable of building an automobile, and the brothers ended their contract with Ford and decided to build a Dodge Brothers automobile in 1914. As the relationship with Ford continued to deteriorate, the brothers joined a lawsuit, in 1916, to force Ford to pay dividends to his stockholders. It was around that time that John Dodge was quoted as saying, “I am tired of being carried around in Henry Ford’s vest pocket.” In 1919, the brothers sold their Ford stock for $25 million, making them among the richest men in Detroit.

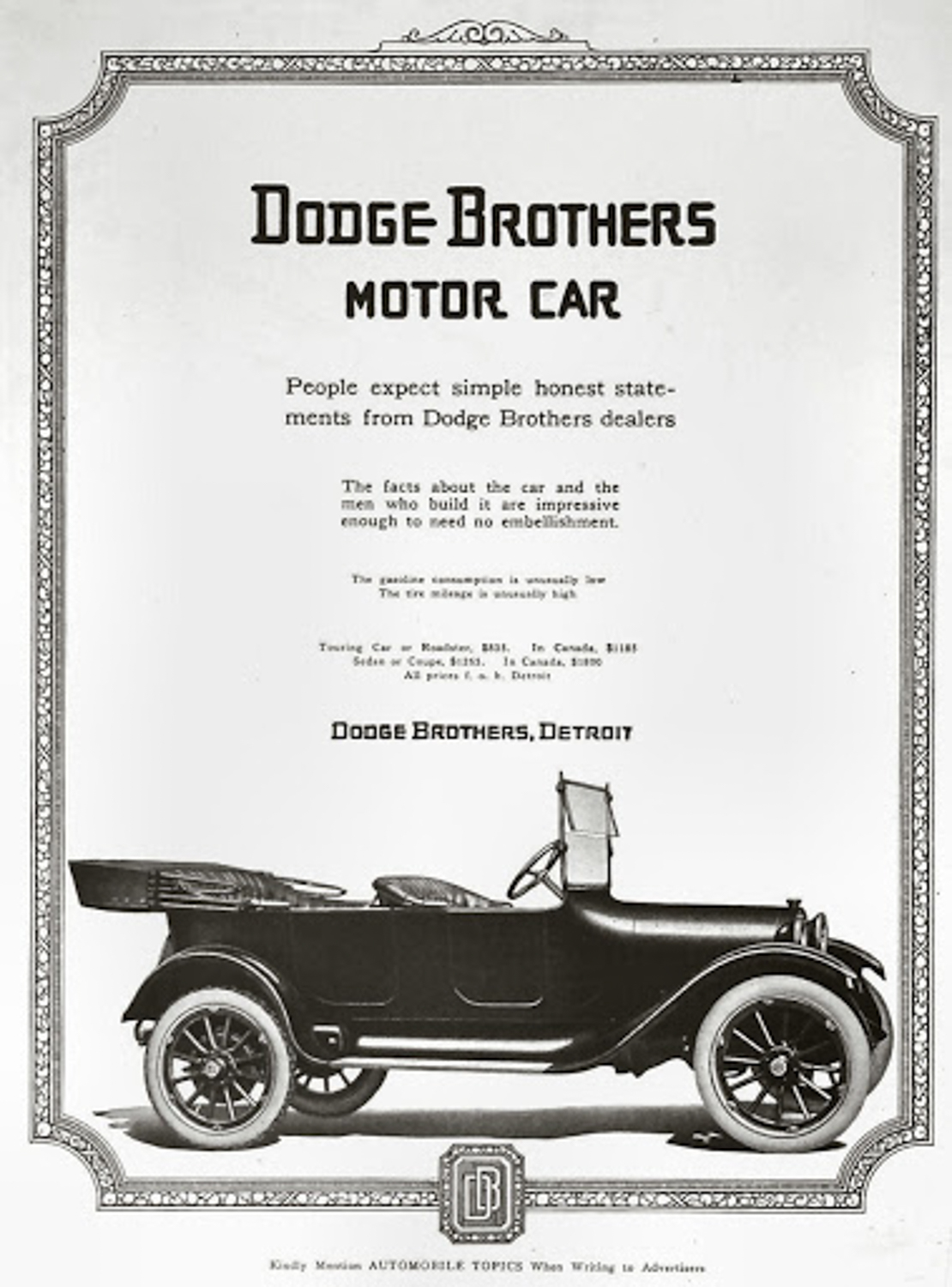

The opinion the brothers had of Henry Ford is obvious in their answer to the question why they decided to build a car. Once again, it was John who replied: “Just think of all those Ford owners who will some day want an automobile.” Automobile Topics said the decision to build a Dodge Brothers automobile was “like the announcement of a new gold strike – another Comstock Lode or a second Klondike – that the famous Dodge engine builders were to have a car of their own.” As a testament to their reputation, 22,000 automobile dealers asked for a Dodge Brothers franchise before the first car was built. The first dealer was John H. Cheek in Nashville, Tennessee.

The brothers and Frederick J. Haynes transformed the factory from making components to building automobiles. The first Dodge Brothers automobile, named “Old Betsy,” rolled off the production line on November 14, 1914. Guy Ameel, Supervisor of Production, drove the brothers around Detroit in Old Betsy that chilly November day. Old Betsy was the prototype for their five-seat tourer; the only model they would build initially. It was designed for the mass market. It was powered by a 3480-cc, 35-hp, L-Head, four-cylinder. It had a three-speed transmission with a direct drive third gear. It was the first mass produced automobile with an all-steel body, built by the Budd Company, and it would sell for $785. The brothers considered it a proper car, unlike the cars being produced by Ford.

The brothers produced and sold 45,000 cars in 1915. That increased to 71,400 in 1916, making Dodge Brothers the fourth best selling auto manufacturer in the U.S. The first retail sale of a Dodge Brothers tourer was on December 22, 1914. Much later, after WWI, salesmen at John H. Cheek sold a car to Sgt. Alvin York and taught him how to drive it.

A two-seat roadster was added in 1915 and a light truck in 1917. The roadster apparently impressed the Army, and a number of them were purchased for General “Black Jack” Pershing’s campaign against Poncho Villa in Mexico. Dodge trucks and car were used by the U.S. Army in WWI. The company was approached in 1917 to build the recoil mechanisms for French 155-mm canons, which they did at a new plant and taking no profit for the work.

The brothers became very wealthy, and they contributed a lot of money to charities. They were also very fair to their workers. They even provided beer and sandwiches for the workers for their lunch. All that would change, unfortunately, as a result of a trip to the New York Auto Show in January 1920. While there, Horace contracted pneumonia. He became quite ill, but rallied. Then John fell ill with the flu, which developed into pneumonia. John Dodge died on January 14, 1920. Horace never really recovered, and he too died on December 10, 1920. Each of the brothers’ widows received half of the company.

Haynes, who had worked closely with the brothers had the trust of the widows and became President and General Manager of Dodge Brothers on January 11, 1921. It was a challenge to run a company when having to report to a Board of Directors and to the widows. Neither the widows nor their children were interested in running an automobile company, so they eventually decided to sell. It was bought for $146 million by Dillon, Reed, & Company, a New York bank, in 1925. There were management changes, a wood-framed body was added in 1925, and a sports roadster was offered in 1926. The company went back to an all-steel body, using the Budd Company design, in 1928. But the company fell from 5th to 13th in production in those years. There were new models using six-cylinder engines – Standard Six, Senior Six, and Victory Six. They were longer, lower, and good looking, but the various models sold for $945 to $1170, much more than a Ford.

The company was in trouble. It could not meet payroll. Stan Grayson, in an article in Automobile Quarterly (Volume XVII #1) titled “The Brothers Dodge,” said “Dillon had milked the company for what he could get and now he wanted out.” Dillon approached Walter P. Chrysler about buying the company. Chrysler wanted to compete with Ford, and he needed a lower priced line, so the company was sold to Chrysler in July 1928 for $170 million. For that, Chrysler got the foundry and forge shops—facilities that were five times the size of the Chrysler plants -—as well as the dealer network. With new management, Dodge was back to seventh place in production for 1929. The next year, ads for the cars referred to them as Dodges not Dodge Brothers. The former name and the six-pointed star on the badge disappeared completely during the ’30s.

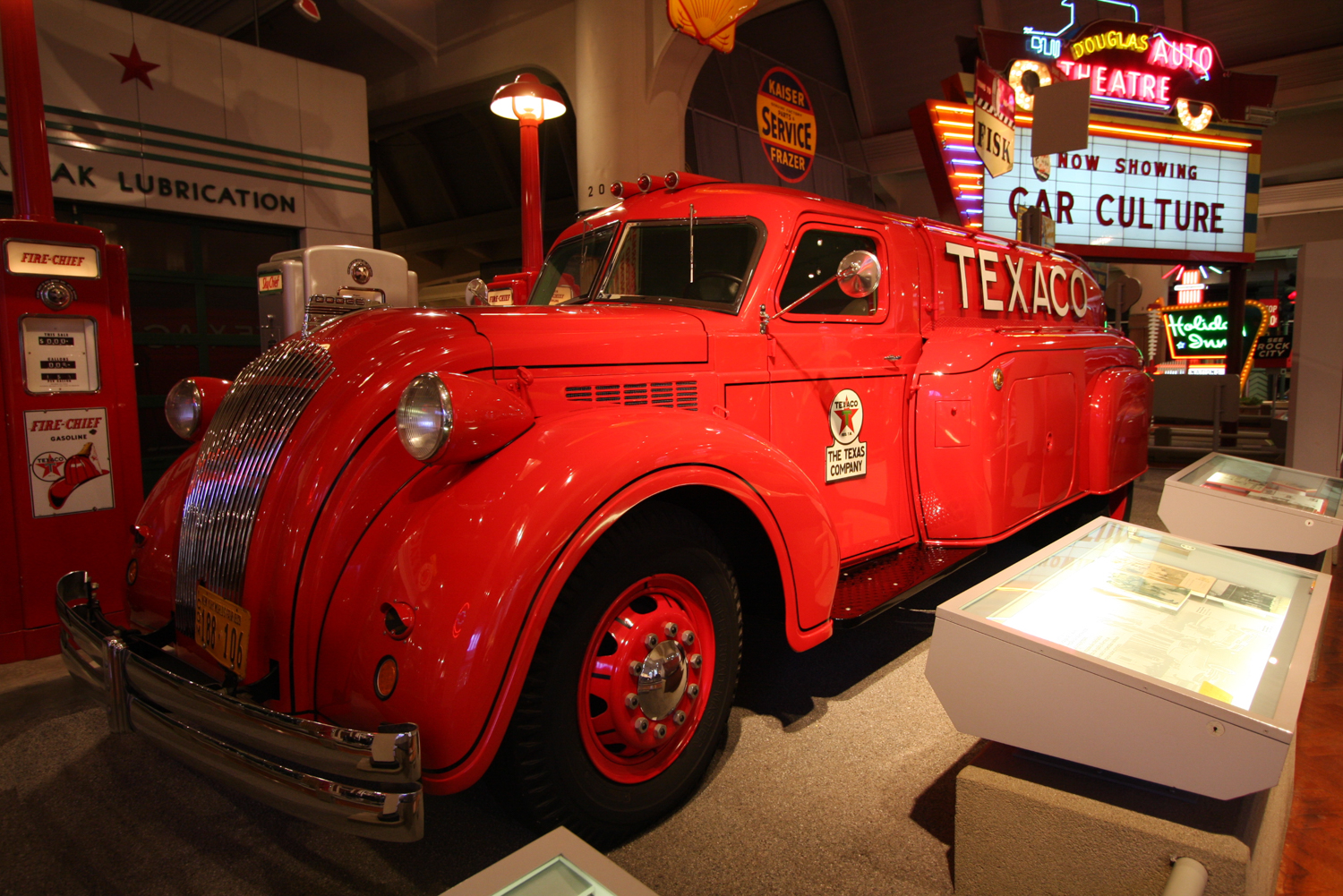

Dodge Division, Chrysler Corporation

Chrysler was only five-years old when it acquired Dodge. Dodge wasn’t the lower priced car Chrysler wanted, but with the new facilities, he was able to introduce the Plymouth, which would be the bottom of the Chrysler line. Dodge took its place in the low-to-medium price category. There were new models in 1930, including a straight-eight engined car that cost less than the old Senior Six. The new models were smaller, lighter, and faster than their predecessors, and they cost less too. From 1933 to 1937, Dodge moved steadily up the sales charts until it was in fourth place, leading in that low-to-medium price range. There were a lot of engineering improvements once Dodge was part of Chrysler, including hydraulic brakes in 1928, freewheeling in 1932, and a synchromesh transmission in 1933. One thing Dodge did not get was the Airflow styling that appeared on Chrysler and Imperial cars. The only Airflow Dodges were trucks. Trucks became an important part of Dodge’s market during the 1930s and have remained important to the present.

Dodge replaced its straight-eight engines with a variety of inline sixes, which they continued until passenger production was stopped on February 21, 1942. Before production turned to the war effort, Dodge added an automatic transmission as an option. Dodge, like all domestic manufacturers, turned to the manufacture of war materials, especially trucks for American forces, including the iconic Power Wagon.

There was little difference between a 1942 Dodge and those produced from 1946 to 1948. Dodge was seen as a pretty uninspired marque. Then came the 1950s, and Dodge took a very different path than it had before. The Red Ram V8 was introduced in 1953. It was a 3954-cc Hemi producing 140 bhp. It was a wonderfully flexible engine. It grew first to 5130-cc and 260 bhp, then in 1970 to 6980-cc (aka 426 ci) and 425 bhp. Dodge had shucked its dull image for one of performance. With this V8, Dodge broke 196 AAA stock car records at Bonneville.

Win on Sunday; Sell on Monday

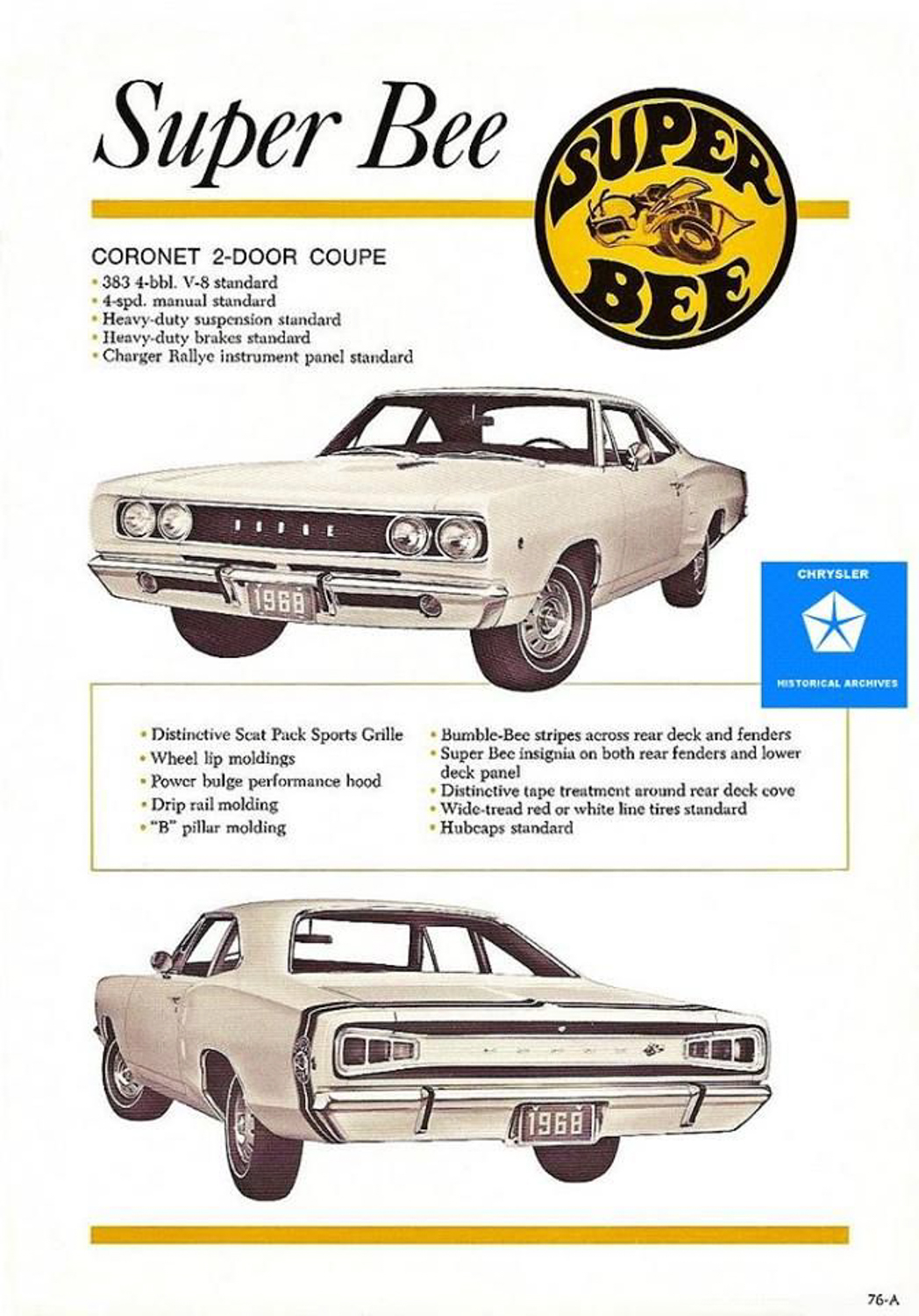

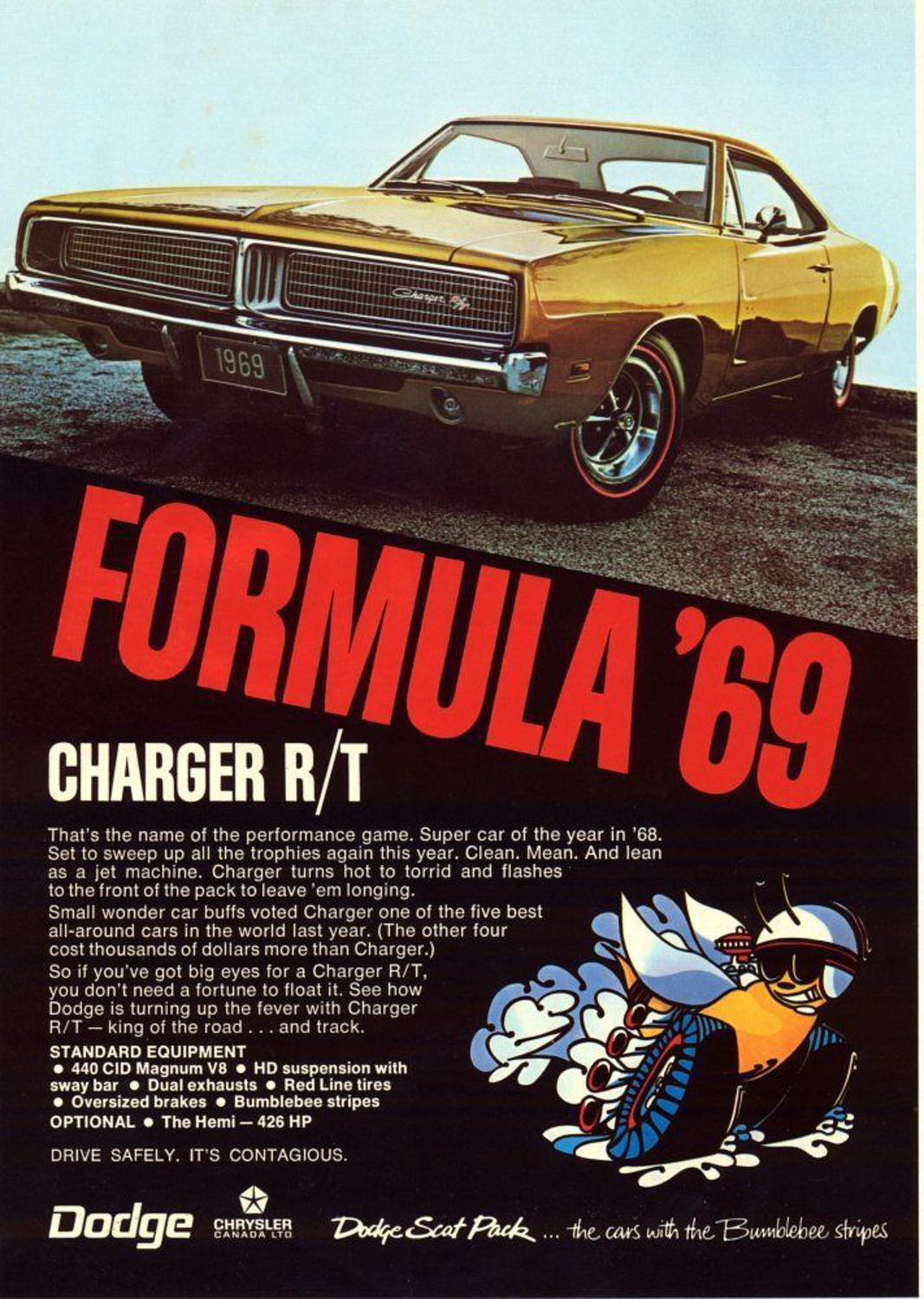

The major manufacturers had officially supported a ban on involvement in motorsports into the 1960s. Lynn Townsend was President of Chrysler in 1961, and he took a lot of grief from his teenage sons because Chryslers were for old people. Townsend is reported as having said, “You can sell an old man a young man’s car, but you can’t sell a young man an old man’s car.” That began an intense focus on performance. The Ramcharger 426 cid engine of 1962 produced 415 bhp with one four barrel carburetor and 425 bhp with two four barrels. As the 1960s progressed, Chrysler produced its “Scat Pack,” including the Charger, Super Bee, Dart GTS, and Coronet R/T. Still, there was little joy for Chrysler in NASCAR, where they really wanted to win.

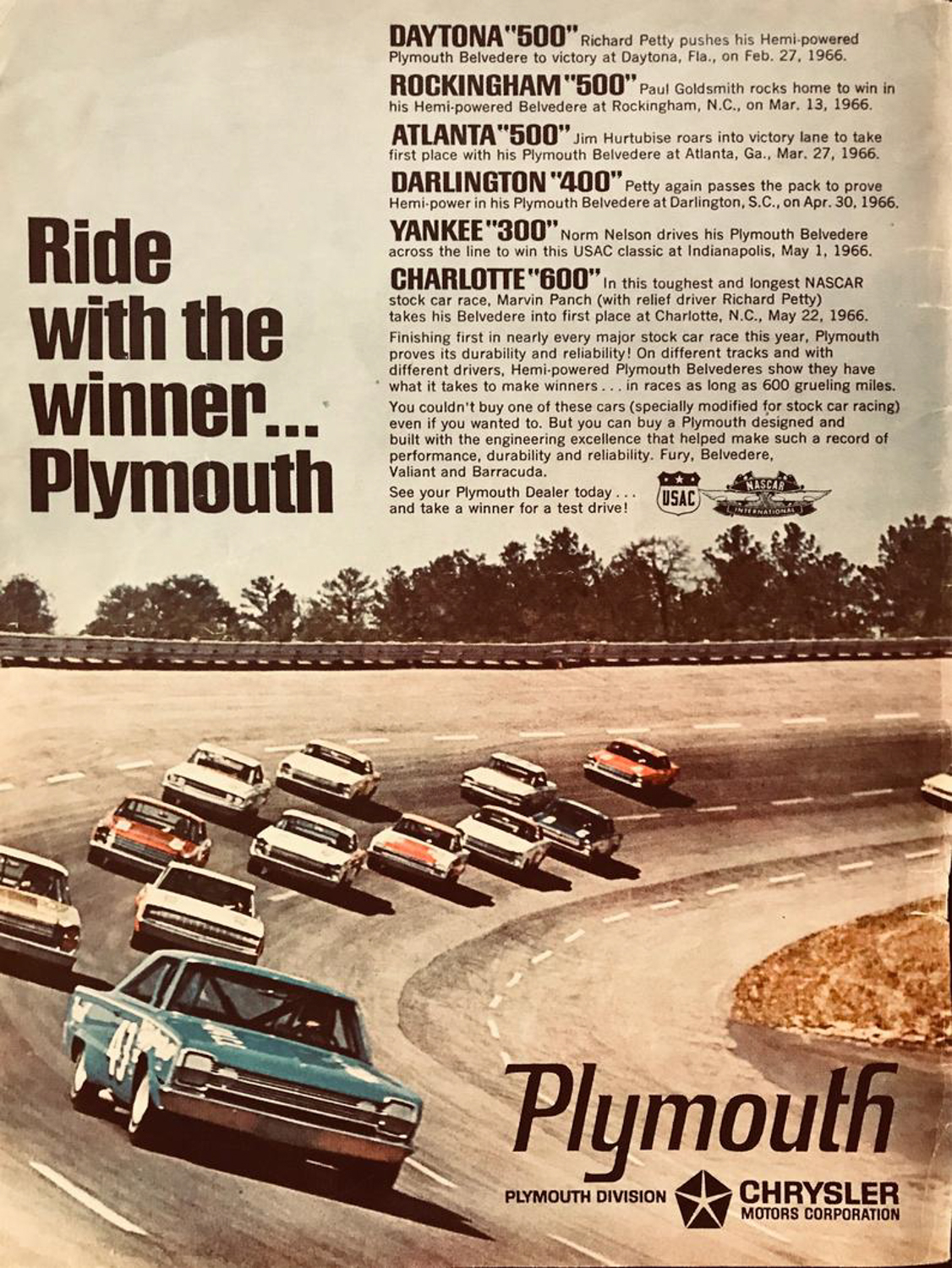

Ford decided to return to racing in 1962, openly providing factory support to teams racing Fords. Chrysler joined Ford in 1963 and formed their Special Vehicles Group in 1964. There was a strong belief that, while racing improves the breed, victory boosts sales. The target was NASCAR where the racecars looked like the cars the company sold. Dodge and Plymouth racecars benefitted from an aggressive research and development program. The immediate result was the sweep of the first three places at the 1964 Daytona 500 by Plymouths. There were 62 sanctioned races in 1964, Ford won 30 races, Dodge won 14, and Plymouth won 12, making Richard Petty the champion in his Petty Blue Plymouth. But Chevrolet and Ford protested Chrysler because the 426 Hemi was not available in any street cars. Bill France, who made all the rules in NASCAR, banned the 426 Hemi and the Ford HI-riser from competing in 1965, so Chrysler sat out the season. The result was considerable gnashing of teeth in the NASCAR headquarters, so France decided to allow displacement up to 430 cid. For the 1966 NASCAR season, the 426 Hemi was installed in the Dodge Charger and Plymouth Coronet sedan.

Chrysler had done extensive testing of the 426 engine, often to destruction on the dynamometers. Racecars with Hemi engines installed were tested on Chrysler’s high banked, five-mile oval at Chelsea. The engines proved to be very tough. Chrysler admitted to 425 bhp, but some thought the engines might be producing as much as 550 bhp. Still, more speed was needed, and it was accepted that it was easier to get more speed through streamlining than by producing more horsepower. There had been nearly no serious aero research in the auto industry since the 1930s, until Chrysler decided to make a bold move. Reductions in NASA research had affected the Chrysler missile division, and a number of aerodynamicists were laid off. One of them, John Pointer, got a job with the auto division and was assigned to work at Chelsea. His job was to develop a system to test the aerodynamics on actual cars rather than on wind tunnel models. The tests were to have “enough accuracy so we could cheat at stock car racing and get away with it.” This was possible because NASCAR had not seen the need for body templates yet. An early result was that Petty’s Plymouth for 1966 had a somewhat less than stock body shape. The front end of Petty’s car was slightly rounded, the hood curved down near the grille, front fenders were not quite straight, and the wheel wells curved slightly inward.

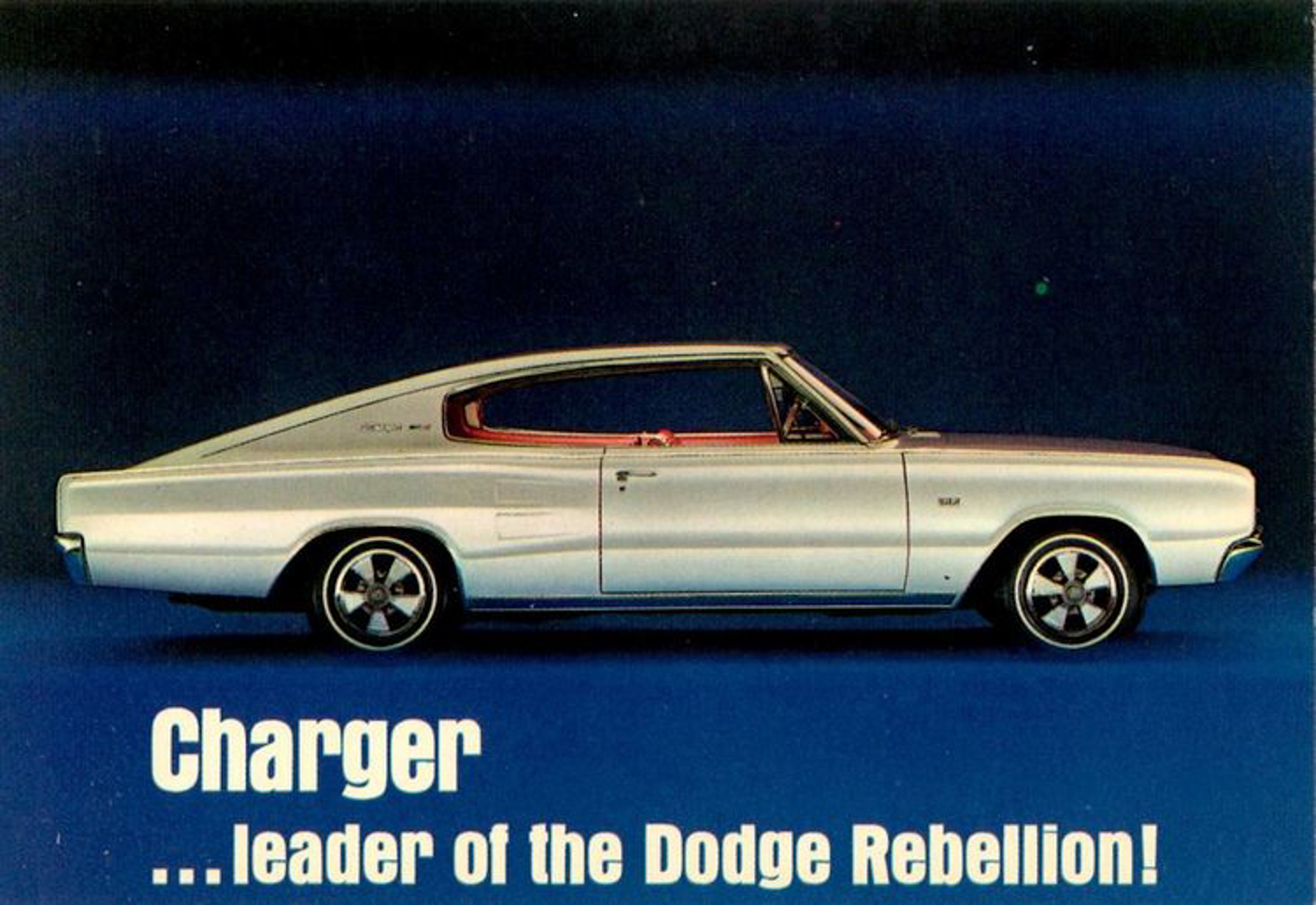

Over at Dodge, the need for something new was solved with the Charger, an affordable “sports sedan” that Dodge called the “Dodge Rebellion” in their ads. With an optional 426 Hemi, it was a very popular and powerful car. In its first half of a year, 37,000 were sold. The styling was new and bold, but it was also not particularly aerodynamic. The front was flat, allowing air to go under the front bumper. Combined with the fastback rear, the car became an airfoil that produced considerable lift. The handling of the car was horrid at speeds over 165 mph. That did not bode well for its performance in NASCAR. Poor performance in NASCAR affected sales in 1967, so the lift had to be addressed. The solution was a 1.5-inch spoiler on the rear of the car. However, there was a problem – NASCAR had now implemented body templates, and the spoiler had not been authorized. France, ever the practical rules maker, decided to allow the spoiler, since he saw benefit in having Dodge be competitive. Still, Petty was again the champion in a Plymouth.

Dodge made changes to the appearance of the Charger for 1968, but they did little to improve race performance. The recessed grille trapped air, and the recessed rear window caused turbulence. The car was several miles per hour slower than the Fords on the ovals, so there were more changes for 1969, including a flush grille with a chin spoiler and a rear window flush with the roofline. The car was now the Charger 500. Race modifications were done by Creative Industries outside Detroit and the cars were sold at a loss to get them on the race track. A decision at Plymouth not to make improvements on the Road Runner made Petty want to race a Dodge. When he was refused by Dodge, he switched to Ford for the season.

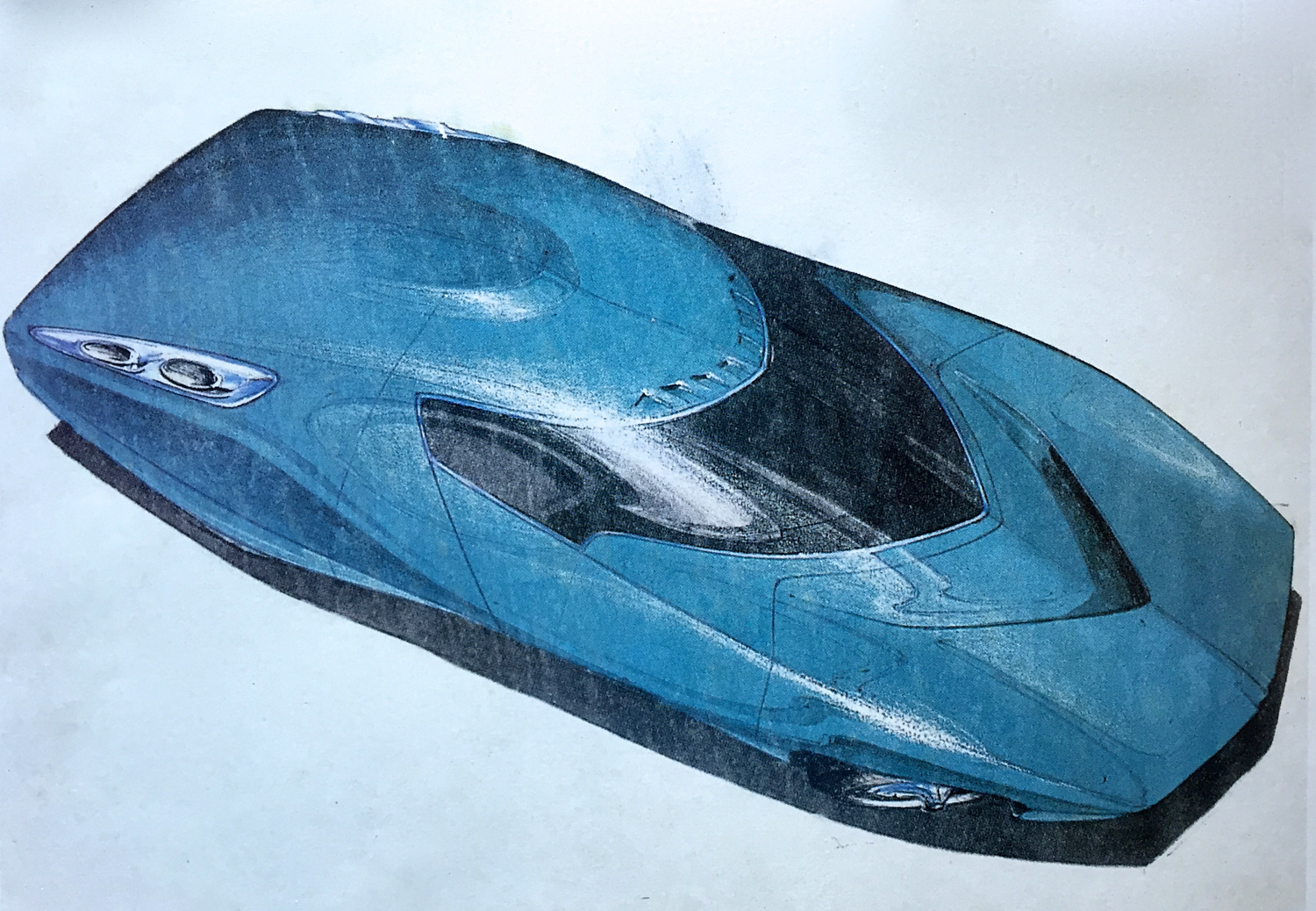

The Charger 500 did not perform well at Daytona in February 1969, and the company decided it had to find a better solution. Larry Rathgeb was lead engineer on the project [Rathgeb sadly died in 2020 from the coronavirus], and he sought out Pointer and Bob Marcell, another aerodynamicist, about what could be done to make the cars winners. Pointer and Marcell had been involved in rocket and missile design and, working independently, developed very similar solutions. Design, testing, and homologation had to be done quickly, since the cars had to be introduced by April to be eligible in NASCAR for the season. Both solutions included a nose cone and a rear wing on pillars. The nose cone directed air flow smoothly over and under the front of the car, and the wing produced downforce, aka negative lift. The nose cone added 18 inches to the car’s front end. The wing was a “Clark Y Airfoil.” It was flat on the top and curved on the bottom, the opposite of an airplane wing, resulting in negative lift or downforce.

The testing, development, and production was not going to be cheap, so Bob McCurry, head of Dodge, had to be convinced. Apparently, he was convinced that these Dodges would win, and he approved the project. But he wanted the cars to race in the Talladega 500 in September 1969, and it was already March. The schedule was crazy. A small team was assembled, modifications to the cars were done at Creative Industries, and the cars were tested on the Chelsea track and in wind tunnels at Wichita State and Lockheed. Stylists tried to get involved in the final design, but their suggested changes were quickly shown to slow the cars potential stop speed. These were cars that would be designed by engineers no matter how much the stylists hated them.

Pointer said, we’re going to build a racecar that flies.” To do it, Pointer installed lift gauges on the cars and rode unharnessed inside while collecting the data the gauges produced. Pointer would take readings riding in the back of the racecars while test driver Jerry Wenk drove the cars on the Chelsea oval at from 120 to 175 mph. He then extrapolated the data to predict the car’s behavior at higher speeds. Downforces were much higher than anticipated, so the car’s suspension had to be stiffened to prevent bottoming at speed. Downforce on the nose alone was 900 pounds! One interesting rule they had was to only start the hemi engine cars outside – they were afraid the noise would break windows in the building.

Various nose cone and wing shapes were tested to find which produced the best speeds. Results of the wind tunnel tests were sent to Detroit. Fiberglass parts were built then sent to Chelsea for track testing. One thing track testing showed was that the new car could not be drafted easily by cars following it. That led Wenk to say, “We could draft, and they couldn’t.” The battle with the stylists wasn’t over, however, even as final decisions were being made. The stylists wanted to modify the clay model that Creative Industries was to use to finalize the car’s shape, but McCurry put a stop to that, saying, “I don’t give a shit what it looks like. It goes fast. If you can’t help, get out of the way.” The engineers had won – the stylists got out of the way. Creative Industries and other suppliers built the parts. The aero engineers at Chelsea put the parts and gauges on the cars and ran laps averaging 200 mph.

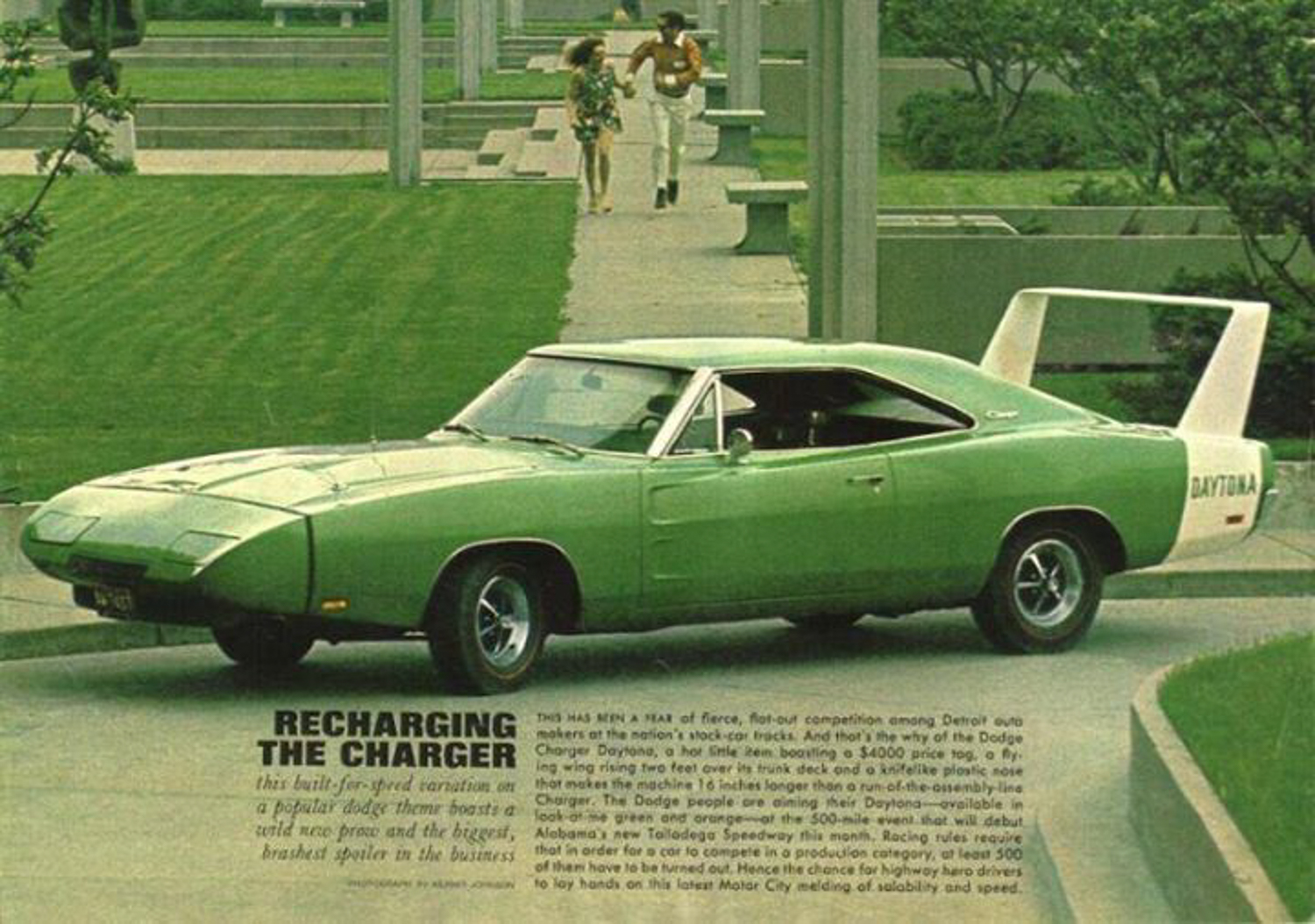

There were a lot of mixed reviews of the Daytona when it was released. Speed and Supercar magazine said, “It was not designed to be pretty, pleasant to the eye, or earth-shattering in appearance. It was designed to do a job.” Stock Car Racing called it “a howitzer shell with a clothesline hanging over the back.” Still, enough cars were built to meet the homologation requirement for NASCAR. The decision to race the car as a 1969 ½ turned out to be very timely. For 1970, NASCAR changed the homologation rules; they now required 1000 cars or a number equal to one half the number of dealerships to be produced. That would mean 1800-1900 cars for Chrysler. Plymouth’s decision not to change their racecars meant that they had to produce nearly 2000 Superbirds in order to race them in 1970. The Charger 500 was still eligible to race in 1969, since it was very different than the Daytona. Chrysler, not wanting to have two different Dodges racing, decided to give the Daytona body parts to teams that could not afford them. Eventually, the only Dodges racing on superspeedways would be Daytonas. Dodge Charger 500s would race on the other tracks.

Somehow, seven Daytonas were ready for the Talladega race in September 1969. One of the seven was entered by Chrysler Engineering’s first ever factory entry. It was the car’s first race, and it was the first race on this new race track. There had been weather problems that delayed track construction, so eventually construction was rushed, leaving the track in less than optimal condition with an uneven pavement. When David Pearson saw the Daytona, he said, “It scares me just to look at it.” The track, though, scared everyone.

Talladega was so bumpy in places that it affected drivers’ vision. Tires were also affected. The track surface and the speeds were tearing up tires after three or four laps of the superspeedway. Firestone pulled out, and Goodyear had Donnie Allison and Charlie Glotzbach test a variety of tire compounds. There was, at that time, a Professional Drivers Association (PDA), essentially a driver’s union. The PDA decided that conditions that were so bad that they, including Petty, pulled out of the race. During practice, Chrysler corporate ordered the Engineering car not to exceed 185 mph, since they didn’t want to show up the Nichols Engineering car or those teams who obtained parts from Nichols. Glotzbach, in the Engineering Car, turned laps of 199 mph, much to the displeasure of the corporate attendees. It was ultimately decided that the Chrysler Engineering Daytona would not run. With other defections, France opened the race to Mustangs and Camaros to fill the field. There were also non-PDA drivers available to drive some of the cars abandoned by PDA drivers. Richard Brickhouse resigned from the PDA to drive the Nichols Engineering Daytona. Nord Krauskopf, owner of K&K Insurance and the #71 Daytona driven by Bobby Isaac said that he had agreed to race, so they would race, even if Isaac had to slow to save his tires. During the race, cautions were thrown about every 35 laps to allow crews to change tires. The Daytonas were particularly susceptible to tire wear because of the additional 900 pounds of downforce on the front of the car and 600 pounds on the rear. Daytona crews tried to slow their drivers down, but it was fruitless. At the checkered flag, Brickhouse had won ahead of two Charger 500s and Isaac. The closest Ford was 24 laps down. Only 16 of the 36 starters finished. So, “Win on Sunday; Sell on Monday”? Within three weeks, Dodge had 1200 orders for the 500 cars that had been homologated. Fearing a lack of sales, Dodge had priced Daytonas at a $1500 loss.

The next speedway race was at Charlotte for the National 500. Seven Daytonas were entered, including the Nichols car driven again by Glotzbach. There are always games being played between teams and the inspectors in NASCAR. At Charlotte, Glotzbach installed a “trim wheel,” a device used in airplanes to control the elevators. He ran a cable to the rear of the car, but it was not attached to anything. He said, “It drove the NASCAR people crazy.” He revealed the joke after the race, which was won by Donnie Allison in a Ford after Isaac broke his engine. Daytonas finished second through fourth. At Rockingham, a high banked one-mile track, Bobby Allison tested both Dodge racecars for four days, and the Daytona was better than the Charger. Glotzbach and Dave Marcis, in another Daytona, were on the front row. Isaac led 43 laps before another engine failure, leaving Ford first and second, Buddy Baker third in a 500, and Marcis fourth.

The Texas 500 was the last Grand National race of 1969. Isaac qualified seventh with the top eight cars all within one second. Isaac’s crew chief, Harry Hyde, was concerned about tire wear and used practice to have Isaac scuff 34 sets of tires. At Lap 180, Isaac was three laps down but was working his way through the field thanks, in part, to the scuffed tires. Buddy Baker was leading at that time, but his car owner, Cotton Owens, showed him a pit sign during a caution. It said: “You’ve got it made. $.” While trying to read the sign, Baker rear-ended another car. He eventually retired but was classified eighth. Isaac’s move through the field had him in the lead at Lap 239 after Donnie Allison’s Ford overheated. Isaac won by two laps; Daytonas were first, fourth, sixth through ninth, 23rd, and 33rd.

Plymouth reversed its decision not to change their racecars and decided to build the Superbird for 1970. There were a lot of glitches on the way to getting a racecar. On the positive side, the Superbird got Petty back from Ford, and Chrysler allowed Plymouth to sell racing parts. But Plymouth initially allowed their stylists to get involved – it was nearly a disaster. Finally, the car was designed, but Plymouth now had to build 1,920 cars to satisfy the NASCAR homologation requirements. Because of a slow start, 37 cars a day were required to produce the 1,920. While the new NASCAR rules made it tough on Plymouth, they also made it less likely that Ford or Chevrolet would build a new model, since they would have to produce 5,000 of the cars to have one on the race track. Unlike the Daytona, which had a much smaller production run, sales of the Superbird were not strong.

There was one aero feature that was not what it was claimed to be. Two things on the winged cars reduced drag – a long nose reduced drag by 9.5%, while a short nose would reduce it by 12.5%. The scoops over the tires reduced drag by an additional 3%. Total drag reduction of all the features, including the nose and scoops, was 19%. The goal was 15%, so the designs were quite successful. The scoops had a potential problem – they were not allowed as an aero device under NASCAR rules. Their purpose, of course, was to relieve pressure from under the engine compartment caused by all the air the nose directed under the car. There was a NASCAR rule that allowed fenders to be cut for wheel or tire clearance as long as it was approved by a NASCAR inspector. The Chrysler engineers put the scoops directly over the tires and claimed that the car’s aero shape caused the tires to hit the inside top of the fenders at high speeds. NASCAR accepted the reasoning and approved the scoops. There were some people, including a magazine, which figured out the real reason, but apparently none of the other teams did.

The first race for the two winged models was the Motor Trend 500 at Riverside Raceway, in California. Dan Gurney was on pole in a Superbird, and Superbirds finished second (Petty), fifth, and sixth (Gurney). The best Daytona was seventh. At the Daytona 500, Baker did a lap in practice at 191.540 mph in a Daytona. The race was won by Pete Hamilton in a Petty Enterprises Superbird with Pearson second in a Ford. Winged cars took 11 of the top 20 places. Rockingham saw a total eclipse of the sun during qualifying, but that probably can’t be claimed as the reason that winged cars took the top five places on the grid. Bobby Allison was on pole; Petty won, and winged cars took first, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth. An interesting rule was introduced by NASCAR at the Atlanta 500 – all cars had to remove their side window glass in order to reduce debris in a crash. It also slowed the winged cars, but not enough to stop Bobby Allison from winning in a Daytona. Hamilton finished third, and Petty was fifth.

With new pavement at Talladega, Goodyear introduced its new race tires – slicks would be used for the first time. Isaac was on pole at 199.658 mph, and Pearson was second only a mile and a half slower. Tires proved to be a problem during the race with many blowing. Between tires blowing and engines blowing, many cars were taken out of the race. At the checker, Hamilton was declared the winner, although Isaac may have been the leader by almost a lap. There was a protest, but Hamilton got the official win. Winged cars were 1, 2, 6, 7, 9. The next race was the Rebel 400 at Darlington. It was a difficult weekend for the winged cars. Glotzbach was on pole, but Petty crashed his Superbird in practice and ran a Road Runner in the race. Petty had a bad crash during the race while trying to keep up with the winged cars. Pearson won with Dick Brooks (Superbird) and Isaac (Daytona) second and third.

The rest of the season was much like the first part. Winged cars were often on pole and usually finished well. There were some notable happenings, though. In Michigan (Motor State 400), the scorers cards disagreed on who won. There were nine protests, but France finally resolved it by declaring that Cale Yarborough had won. Wings were half the top ten. Petty won the Falstaff 400 at Riverside by leading 149 of the 153 laps. He even ran out of fuel and coasted 1.5 miles to the pits without losing the lead – now that’s overkill. France instituted restrictor plates at the Talladega 500, but Isaac was still on pole at 186.834 mph. Winged cars led all but three laps of the race. Between crashes and blown engines, the best winged finish at the National 500 was second, even though winged cars led 222 of 334 laps. Isaac was the 1970 NASSCAR champion, Dodges (all types) took 25 pole positions. Chrysler products won 38 races with Isaac winning eleven and Petty eighteen. Ford only won ten race, and GM won none.

Chrysler decided to cut back on racing in 1971, supporting only two cars for Petty Enterprises. Ford decided not to support any teams directly. Apparently, manufacturers found that they were not selling any more cars than they had before, possibly because insurance companies were raising rates on muscle cars, making them more expensive to own. Then there were the rules changes. With Ford and GM whining about the winged cars, France decided to add a new rule that was intended to result in more equity. It said, “Special cars, including the Mercury Cyclone Spoiler, Ford Talladega, Dodge Daytona, Dodge Charger 500, and Plymouth Superbird, shall be limited to a maximum engine size of 305 ci.” Another rule change gave the Hemi engines a smaller restrictor plate than that for wedge engines. One winged car entered the Daytona 500 in 1971. Mario Rossi entered a 305-engined car for Dick Brooks. Brooks qualified eighth, led five laps, and was listed as the seventh place finisher after crashing out.

Nord Krauskopf still had a question about the Daytona he wanted to have answered – how fast could it go? After Isaac won the championship, the team ran the K&K Insurance #71 car at Talladega to test its speed. Buddy Baker had set a record at 200.447 mph in the Chrysler Engineering Daytona, but Isaac set a new World Record for Closed Course at 201.104 mph. That record would stand for 13 years. Then, during a break in the NASCAR schedule, Krauskopf took Isaac, the Daytona, and the team to the Bonneville Salt Flats. Over four days, Isaac and the Daytona set 28 records, all of them run on the same engine. Records were set from 1 Km/1 mile to 100 Km/100 miles. The record set for 1 Km/1 mile was just under 217 mph for both distances. The K&K Insurance Daytona is now a major attraction at the Wellborn Muscle Car Museum in Alexander City, Alabama.

Without racing and with the difficulties in selling the Superbird, Chrysler returned to producing more traditional muscle cars. Model names like Charger and Daytona have been used for a variety of cars since the 1970s, but none have been quite as interesting looking as the winged monsters of 1969 and 1970.

Ledfut’s Daytona

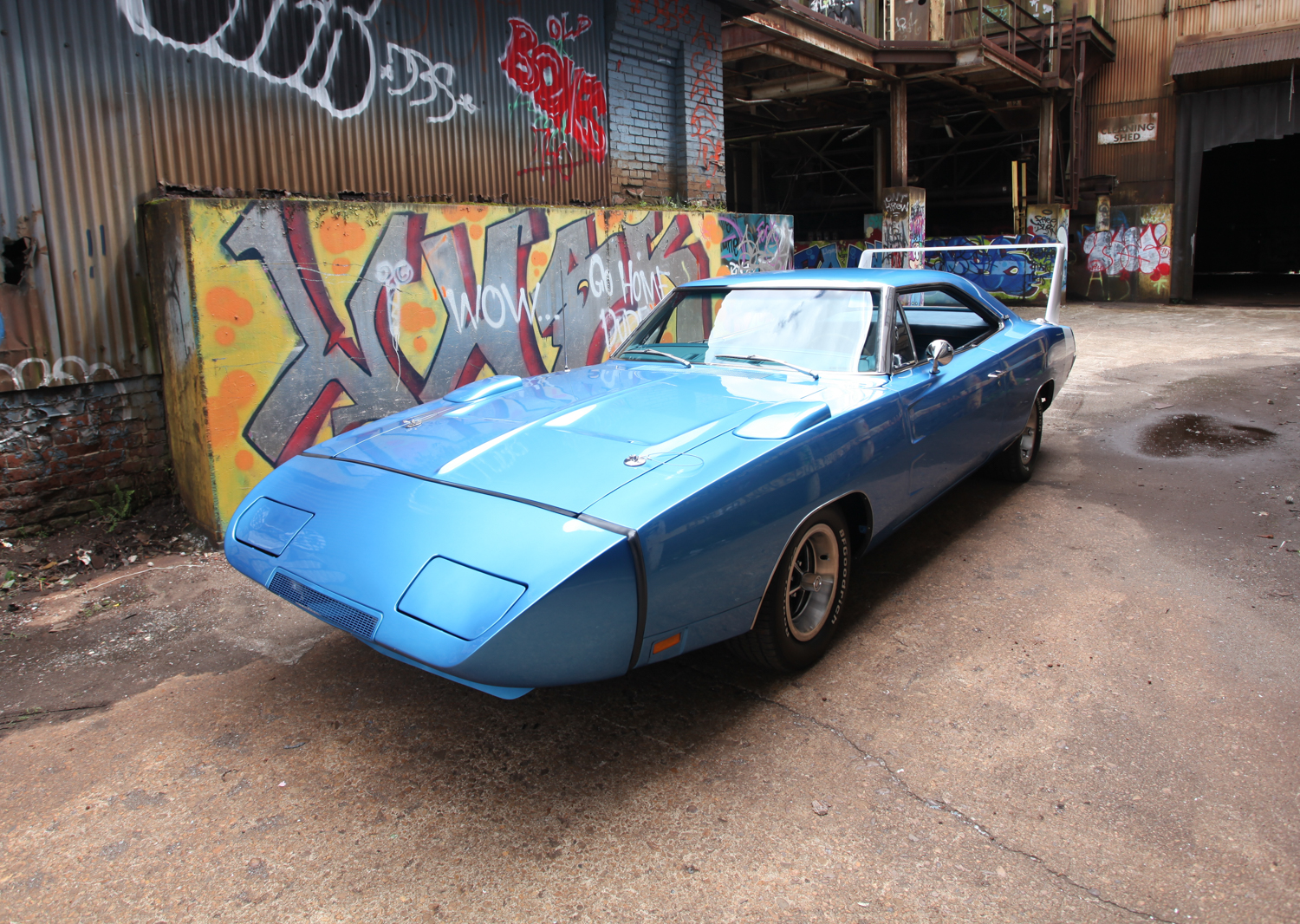

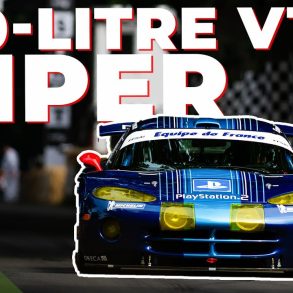

Ken Stonebrook’s nickname is “Ledfut.” It’s a very appropriate nickname for a guy who has several very quick Chrysler products in his garage. The coolest of his cars is his blue Daytona with the white wing. The car has been in his family for many years, but it was up to him to restore it. Stonebrook’s father knew a guy in Appleton, Wisconsin, who had a used car dealership specializing in eccentric cars. He had three winged cars – this 440 cid engined car and both a hemi Daytona and Superbird. The cars had been damaged and needed a lot of work, so his father got the car for something like $500 in 1972 or 1973. Even in poor condition, Stonebrook’s father got it running and took it to a drag strip and won a trophy in his class. He let the future Ledfut collect the trophy. Many years later, Stonebrook found the timing slips still in the car’s glovebox.

His father also knew a fellow who raced stock cars in USAC. He had bought all the sheet metal and parts from the factory to create a Daytona, but he never used them. Stonebrook said, “…this car needed all new sheet metal – the nose was crunched; it was in bad, bad condition. Dad bought all [the NOS parts] from him for pennies – I’d like to say around $500. My earliest memories [are that] this car sat behind our shop. We had a shop, and there was an overhang, and this car sat under the overhang in the dirt for 30 years. As a little boy, I’d go out and get in the driver’s seat and envision driving that car. I always thought that someday I’m going to build this car, and I’m going to drive it. That opportunity came about 12 years ago. I told my dad that if he would donate the car and all the stuff he had for it, I’ll donate the labor and I’ll build it. It took about five years of on and off work. It was a lot of work.”

Stonebrook learned a lot about how these car were built. “These cars arrived at Creative Industries as Charger R/Ts. Creative took them all apart. They smashed the back widow out – that’s how they got the back window out – it was faster than cutting it out. When I took this thing apart, there was still glass in the wheel well pockets. They took the interior out, smashed the window out, and sloppily put the fastback insert in there. Then they put the nose, wing, etc on it. They only painted the top half of the car. Sides were original paint, top and nose were blended in. If you lifted the hood on an original Daytona, all the overspray was on the wires and hoses since the hood had a gap. Sloppy. Superbirds were delivered as bodies in white from Chrysler – they had no fenders or bumpers. Creative Industries built them as Superbirds. Birds had vinyl tops to save work painting them – a lot of body work had to be done and a vinyl top saved time. The backlight on the Bird was not as extreme as the Daytona.”

Stonebrook’s idea of working on the car when time permitted changed suddenly when an invitation was received. “There’s a big event that meets every five years in Alexander City, Alabama. Tim Wellborn hosts the Aero Warriors event. We were invited. Only 200 cars got invitations, and we got a special invite. But the car wasn’t done, so I took two weeks off work. My dad came in, and we worked on it night and day. We finished it Thursday night about 10pm. I loaded it in the trailer and left out about 5am for Atlanta Motor Speedway, where the show started. We were able to do laps around the track. There were several of these cars there. The first time in 45 years – first test drive. I thought they’d do 35 mph laps, they were doing 110-115 around the track. Unbelievable experience. Dad was sitting there with me. After about 20 laps, we loaded up, went to Alexander City, and did the event there. Then we went to Talladega and did laps around Talladega on Sunday morning before the big race. That was its second time on the road. It literally had never been on the road prior. We just did this event again in 2019.”

The Stonebrooks, father and son, must be pretty good mechanics for their car to survive its break-in drives to be on Atlanta Motor Speedway and Talladega Superspeedway! At the event, he enjoyed meeting some of the people who built the cars and who raced them. There are a number of signatures on his wing – Bobbie Allison, the Ramchargers, Dave Marcis, Charlie Glotzbach, and the engineers who designed the car – Larry Rathgeb and Gary Romberg – both of whom died this past year from Covid.

There was some serendipity involved in putting this car back together as a numbers matching Daytona. Stonebrook explains: “The car has the original, numbers matching engine. Dad had sold the engine to a friend of his, and it was put in a ’63 Dodge. Dad built that car for racing. But the guy never paid for the work, so dad kept the Dodge until he paid. Twenty years later, Dad thought maybe he’d just give me the car. So, he tracked the guy down – he’d moved away. He gave Dad the title. Dad checked the engine, and the engine number started with XX – only Daytonas started with XX. That’s when he remembered that it was the engine out of the Daytona.” Stonebrook brought the engine home separately and reunited it with the car.

Driving Impressions

Stonebrook and I met to do the car-to-car photography at a boutique shopping area called Cambridge Square. As we were emailing to set up the appointment, he responded with “Look for a blue Daytona in what I’m confident will be a sea of other Daytonas.” Not only is he a good mechanic, he’s got a sense of humor. We met, chatted, and did the photography, but, because of Covid-19, I was not going to drive his car – too close together with a virus that can be spread by non-symptomatic people. So, I asked him to describe what it’s like to drive the Daytona. Here are his comments:

“It drives fantastic. Very smooth and quiet inside. I’ve got other cars like this – Chargers, etc – and I know what they sound like at 80 mph. This car is so quiet inside, the aero is so smooth, you don’t hear the wind buffeting. There are so many things built into this car that were designed to make is slippery. It’s very smooth. The springs and torsion bars are all original, but they’re not so stiff that it’s rough to ride in. It’s a very smooth riding car. Power disc brakes, power steering – all the conveniences. Only thing I wish I had was a/c. It also has a bit of swagger about it. No matter where you go – women, children, black, white, Hispanic – it doesn’t make any difference, everyone wants to stop and talk to you about it. You almost feel like a celebrity driving this car. I love driving the car; it’s the best part of it.”

“Swagger?” Oh yes, it does have swagger. As Stonebrook and I chatted, people were stopping their cars to look at the Daytona, shoppers walked over to peer in the windows, and several people asked about it. This car is the definition of swagger.

Epilogue

Covid-19 is not the first pandemic to affect the automobile industry. Looking back at the early years of the Dodge Brothers, the company went from success to success and showed potential to become one of the big players in U.S. and world automobile industry. Then they decided to attend the New York Auto Show in early 1920 during the Spanish Flu pandemic. Both died as a result of that trip. What might Dodge Brothers have become had the brothers lived? There’s no way to know if the company would have become a world automotive power or if it would have survived the Depression, but it likely that Horace and John Dodge would have done a lot more with their company had they lived.

Note: The static photographs were taken at the former United States Cast Iron Pipe and Foundry Company, now a dilapidated wreck of a complex looking for a new life. In 1969, the company was making brake drums for Chrysler. This may have been a return for the Daytona to the place where it was partly born.

Specifications

| Body Style | 2-door fastback coupe |

| Engine | OHV V8 |

| Displacement | 7206 cc/439.7 cid |

| Bore | 109.73 mm/4.32 inches |

| Stroke | 95.25 mm/3.75 inches |

| Compression Ratio | 10.1:1 |

| Power | 279.5 KW/375 hp at 4600 rpm |

| Torque | 654 Nm/480 ft-lb at 3200 rpm |

| Induction | Carter AFB 4-barrel carburetor |

| Transmission | Manual 4-speed |

| Drive | Rear Wheel Drive |

| Weight | 1865 kg/4110 lbs |

| Length | 5240 mm/226 iinches |

| Width | 1948 mm/76.7 inches |

| Height | 1345 mm/53 inches |

| Wheelbase | 2972 mm/117 inches |

| Front Track | 1516 mm/59.7 inches |

| Rear Track | 1504 mm/59.2 inches |

| Drag Coefficient | 0.29 |

Great article Mike, you really took some time and did your homework! Being a Mopar guy I thought I knew it all… turns out I didn’t.