My association with Team Lotus covered the period from October 1975 until May 1984. After the second season, and particularly after we lost Ronnie, I had started to get on with other parts of my life. I was still involved with Team Lotus on a race-to-race basis, depending on my availability and their needs, and sort of became a super-lurker, meaning I’d be taken care of with food and lodging when I was at the racetrack because I knew the program, I was part of it, but I pretty much had to pay my own way to get there.

At the beginning of the ’81 season, South Africa had been cancelled due to the potential breakup between FOCA and FISA, so Long Beach became the first event of that year. The race was scheduled for March 15, but on the Sunday before, I’m in my flat in Long Beach,and out of the blue I get a phone call from Lotus team manager Peter Collins telling me to go rent a box truck because “we have a pickup to make and I’ll give you the particulars when it’s all set up.” I asked what size, and he said “big enough to put a racecar in.” So I said OK, and Monday I went, with my own money, and rented a two-axle truck that didn’t require a commercial license.

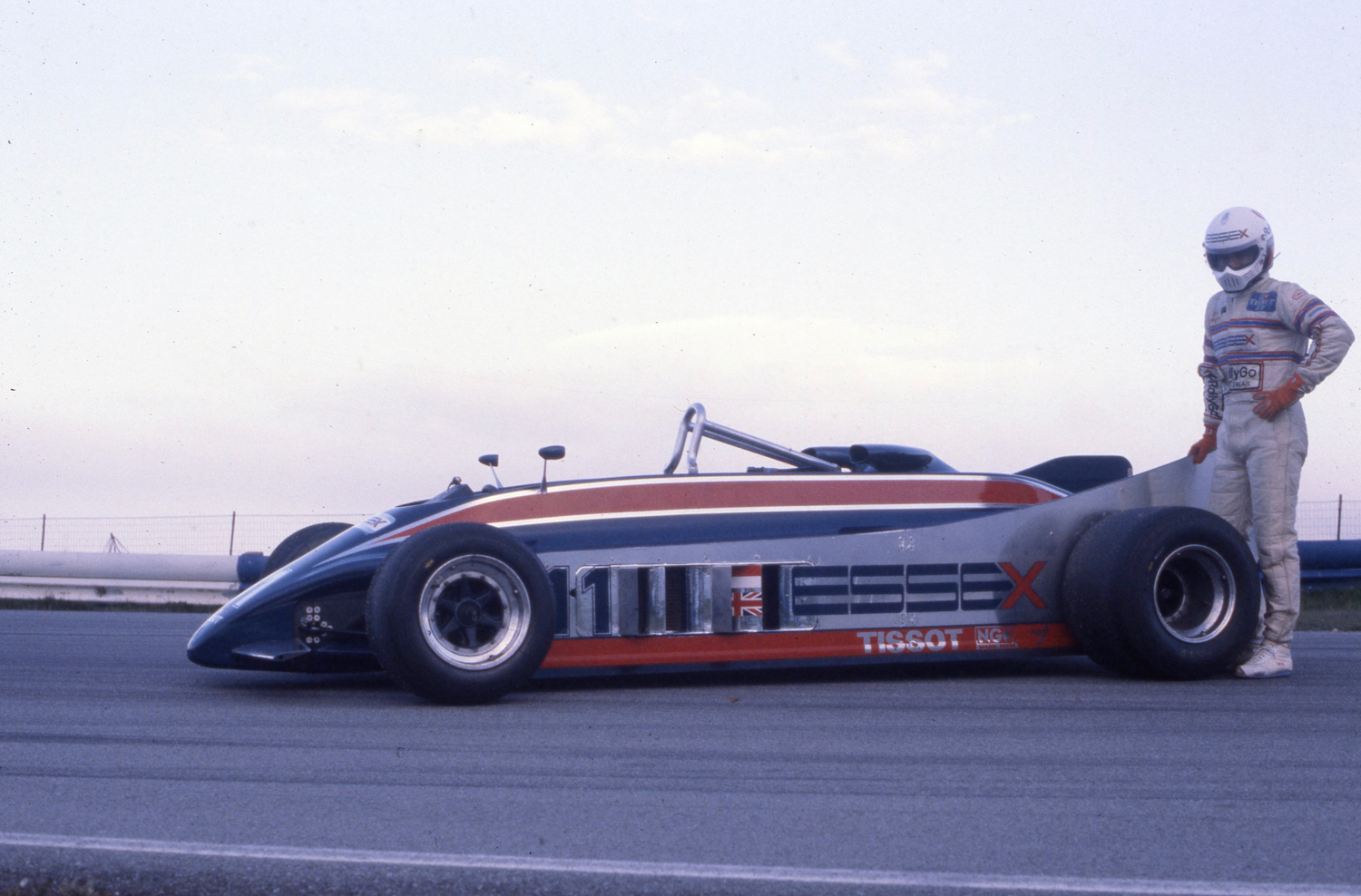

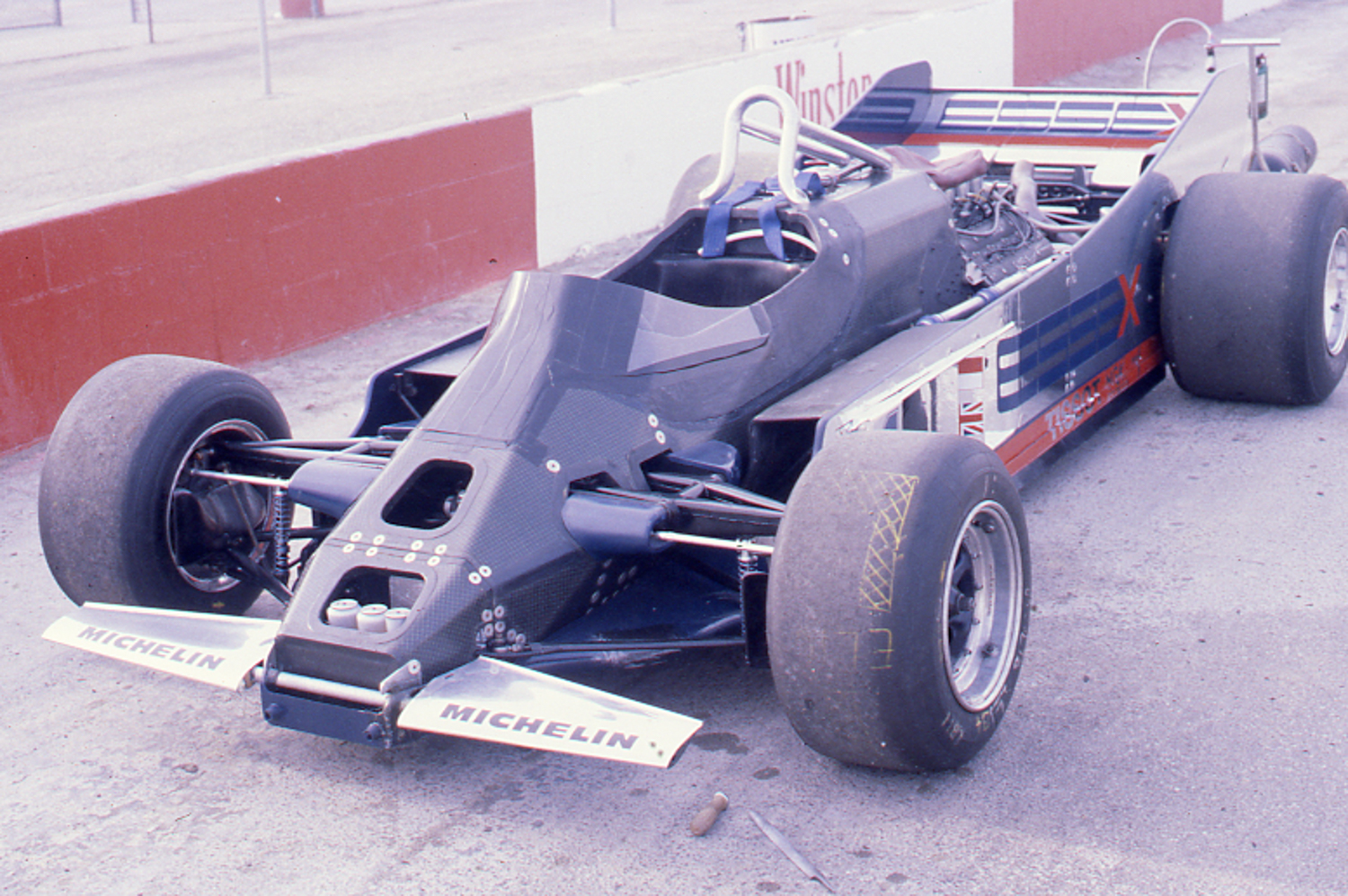

After I got the truck I was told to go collect the car Monday night at LAX. Team Lotus had pre-cleared the car with customs and identified me as the person to sign for and collect the car. The car was on an aluminum pallet and they simply took a big forklift, lifted up the pallet and we were able to roll the car directly into the back of the truck. I took some 4×4 blocks and nailed them right to the truck’s wooden floor to hold the car in place as there was no provision for tying it down inside the truck. I peeked at it, of course, and it was a strange looking car, with the driver sitting way forward as they were doing then, and I thought: “Golly WOW, what are all these little springs?”

So that night the car was sitting in the truck, in front of my apartment, and nobody knew what was inside. During the day on Tuesday I tied it down better and early Wednesday morning I drove out to Riverside, getting there so early that nobody was there yet, not even security, so I just drove in unobstructed to the garage area. I was met there by Peter Collins, Nigel Stepney, Peter Wright and a South African mechanic named Geoff Hardacre. Our first problem was getting the car out of the truck, because we didn’t have any ramps. So we wandered around the garage area and found an old-style hydraulic car hoist at the end of one of the rows of garages. We took the truck over, raised up the lift gate and then put boards on the hoist and rolled the car onto the boards. Here’s a million-dollar racecar precariously hanging with its rear wheels on a hydraulic lift and its front wheels on the lift gate of a box truck.

So, with somebody on every corner, all hands on deck, we lowered it, and to our shocked amazement got it down onto the ground and were able to roll it off the lift and into one of the garage stalls to begin prepping it to run. Shortly after we pushed it out to the pit wall our driver, Elio de Angelis, arrived. Peter Collins and Peter Wright made a reconnaissance lap of the track in their rental car to see if it was clear. When they came back in Elio went out and started knocking off laps, coming in to discuss everything since this was the very first time the car had run, other than a brief shakedown at Hethel, in the UK, for a leak test and to see if the wheels stayed on.

Although they didn’t necessarily articulate it, I don’t think they fully understood what they were trying to do with the car, but they did know it wasn’t fast. It had issues. They played around with front cambers, toe-ins, trying different castor-camber adjustments trying to get the car to turn in and have some front bite. Sometimes it would push and others we would get snap oversteer.

We tested all day, and Elio wasn’t all that happy with the car. It was not quick, it was difficult to drive, and if it had ultimately been approved to race, gone through scrutineering and all, and attempted to qualify and race, it would have been pretty much of an embarrassment. We tested all day and then I was tasked with taking it up to Laguna Seca for the next day. I drove all night to get there, and was met by Bob Dance and Colin Chapman, who had flown in to Northern California. We tested all day. I was not privy to the discussions among the engineers during or after the runs, but you could tell they were not pleased with the performance. These two tests were the first time the car had turned a wheel in anger, so it was all new car sorting-out and the team was confident they could sort it out.

We packed up at the end of Thursday and Bob Dance and I drove down to Long Beach overnight, down Linden Ave. into the circuit and the garage area, and parked with a bunch of other trucks. The car was in the truck, but not in the arena where the other two cars were being prepped. We were then told to go get the car, and by then we’d made some ramps and organized a way to get it out of the truck without all the drama.

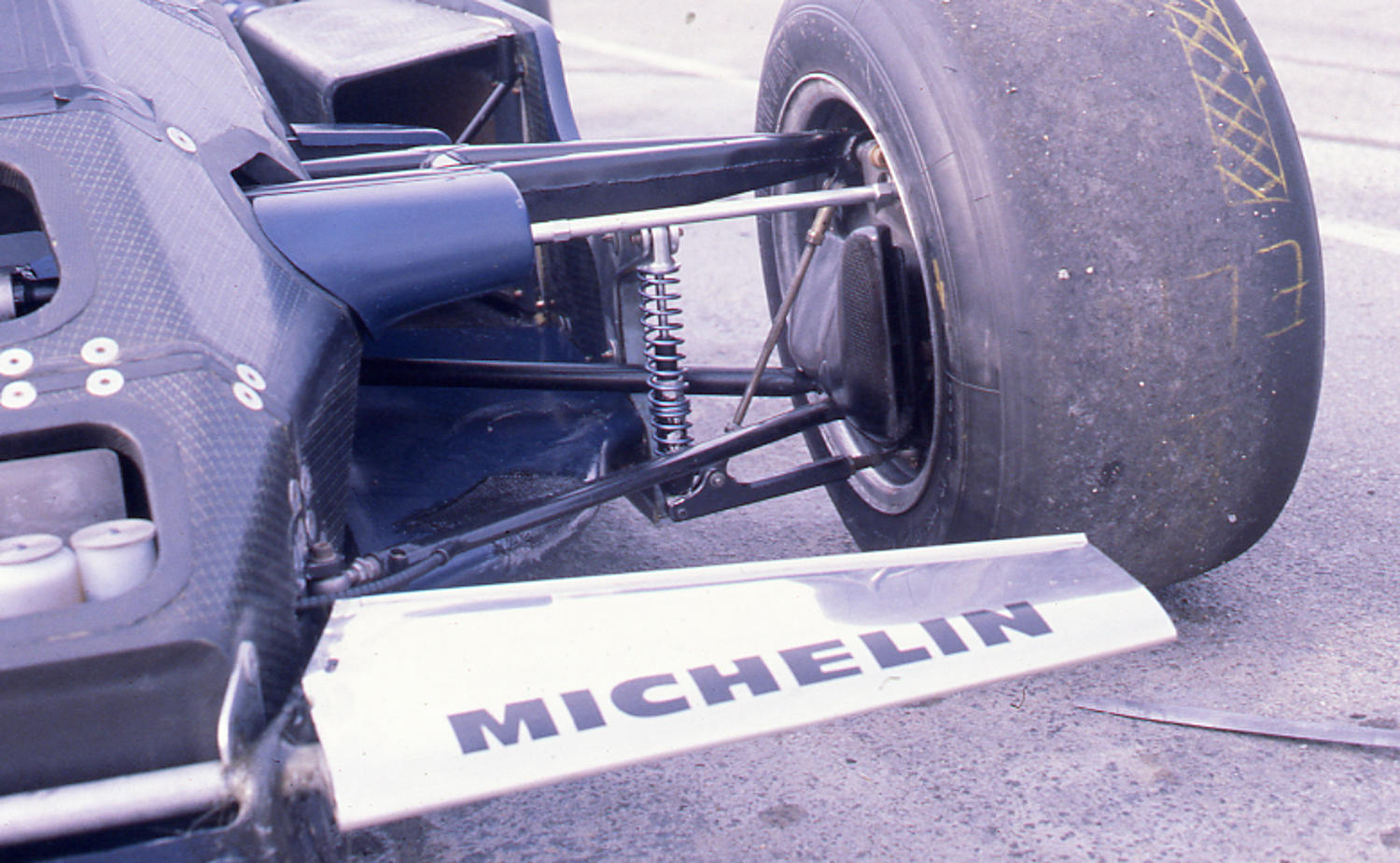

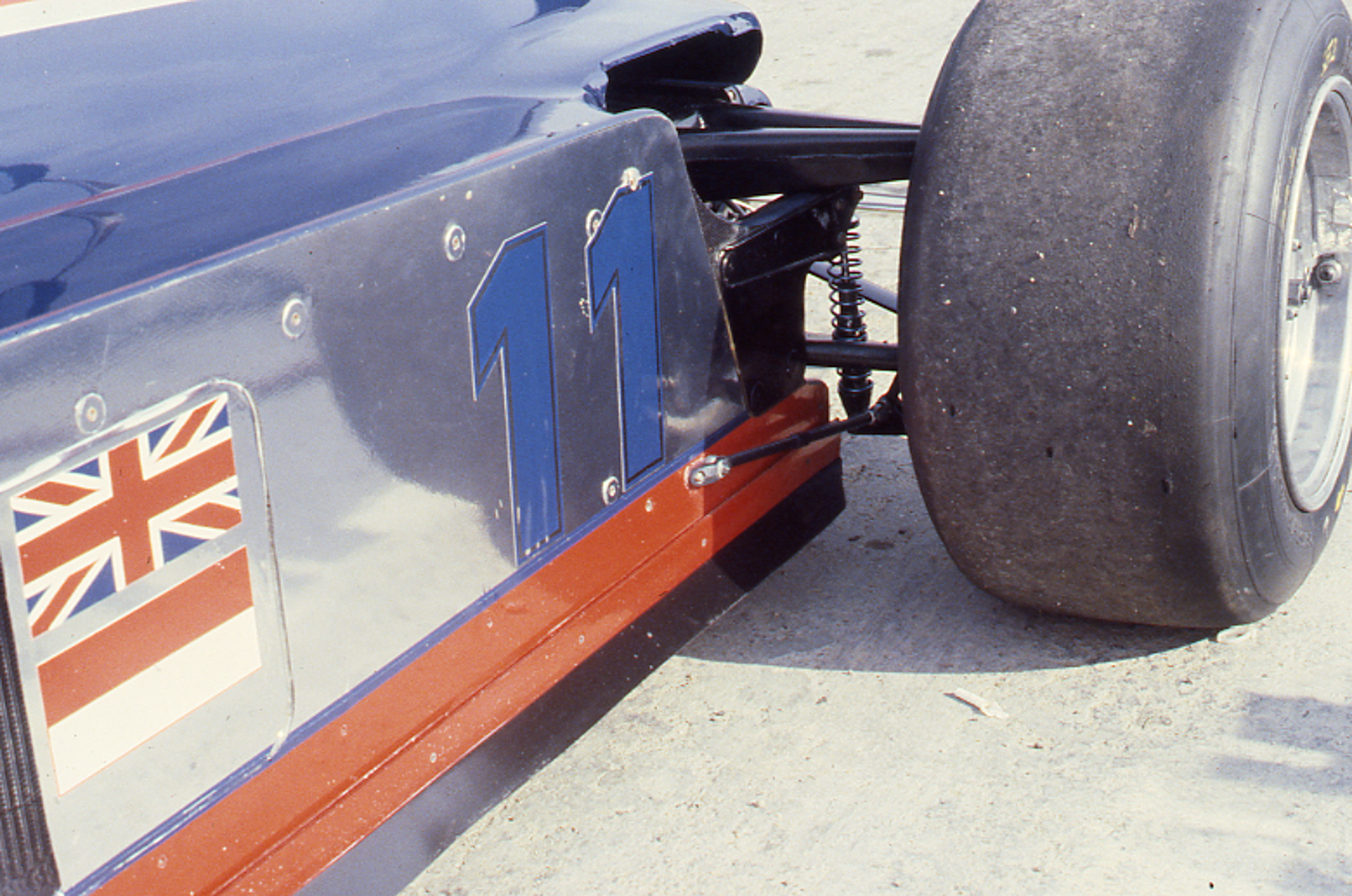

Once it was in the arena, we put fences around it and had it all covered up. Nobody was supposed to see the car, but since all the other teams were also in the arena we couldn’t really hide it from the other participants. When we took it over to scrutineering everybody immediately started gawking at it and cringing and moaning, having seen what it was. Initially, it was approved by the scrutineers on Friday, but then during Saturday’s first session it was black-flagged and we were told it wouldn’t be allowed to run, with no reason ever given.

Chapman’s press conference that afternoon was disjointed because he was so angry and filled with frustration and angst. He was one of F1’s guiding lights — with Ken Tyrrell, FrankWilliams, Bernie Ecclestone and others — a mover and a shaker who was making Formula One what Formula One was, and now to have the entire circus turn on him, that was his biggest frustration. He understood Ferrari, but not the English teams.

Elio and Nigel (Mansell) went ahead and qualified the older Lotus 81, which was very heavy and hadn’t been further developed because Team Lotus thought we were going to have a new car. They were the backups just to get the season started. Although Chapman left the circuit Saturday afternoon, took in a Lakers game and caught a flight to Washington so he could take the Concorde home — missing a GP for the first time in 20-some years. He appealed the disqualification and ACCUS agreed, so he decided to send the car to Brazil.

Two weeks later we were in Brazil, and we thought we were going to be able to run it. Once more we got a tech sticker, but the strangest thing for me—and Chapman too, I guess—was that here’s a car that was technically approved by FISA, yet local scrutineers had the power to allow it to run or not. So who’s in charge? A contemporary report notes that a protest was lodged by the other teams over the car’s legality, although they did not specify what was wrong. Then the scrutineers came back and what they did was to deflate a tire to simulate a tire going down as there was a rule saying the car could not touch the ground with a driver aboard. They went out of their way to make it touch the ground and eventually it did, so we were banned.

Another two weeks passed and we were in Argentina. Even though sponsor David Theime of Essex had his high-dollar Monaco lawyers there threatening lawsuits and everything, by that time everyone was ready to ban the car outright, and it became apparent we were not going to be allowed to run. Chapman left early again.

By that time, he was exhausted, extremely frustrated and very, very bitter. He could not believe his colleagues had done that. Of course, we all learned later their worry was that — like all of Chapman’s innovations and breakthroughs, the Lotus 25, 49, 72, 78 and 79 — everyone else would have to follow suit and take a season and a half to catch up. The worry was, of course, if this twin-chassis car was quick, or even close to being quick, everyone else would have to go in that direction, so let’s just ban it. The same thing had happened with the Lotus turbine at Indy.

When I first saw the 88, I couldn’t believe it. It looked like a space ship! It had a composite chassis with Kevlar weave. Even though John Barnard’s McLaren MP4/1 gets credit for being the first composite chassis, this was slightly before that. I had not seen a composite car. It was all very space age. The bodywork was all one long piece, if the nose were damaged, there was no nose cone you could easily replace, the whole bodywork would have had to be replaced. The sides were just like honeycomb fences. Sadly, the Lotus 88 never gets the credit for its innovation because it never turned a wheel in anger during qualifying or a Grand Prix

Personally, I wanted to see the car have its day in the sun.

As told to John Zimmermann

[button link=”https://dev.sportscardigest.com//subscription-account/subscription-levels/” color=”red”]Like this article? Click here to subscribe and get access to over 7,000 more articles![/button]