Watching it happen, it was hard to appreciate the magnitude of the achievement. The big blue roadster hardly made any noise, and it was being driven with such poise, such command, that its motion around the track didn’t really rivet the eye either.

Yet, as Mark Donohue cruised his turbocharged Porsche Panzer around the final lap of his last Can-Am race at Riverside in 1973, he was climbing a summit of personal fulfillment. The legendary driver-engineer himself said that taming this immensely powerful, initially very difficult machine was “a monument to my career.”

Thirty years later, Donohue’s triumph seems even more remote. We don’t see feats like his anymore, at least not in racing’s top ranks. In today’s more complex, more restrictive environment, any one individual has far less control over the shape and performance of a vehicle.

Yet Donohue was of an era that fostered drivers who founded their own marques—ambitious and inventive men like Bruce McLaren (McLaren), Jim Hall (Chaparral) and Dan Gurney (Eagle). While Mark didn’t create or name the Can-Am Porsche—nor did he work alone, by any means—the sleek supercar certainly bore his identity.

Donohue wasn’t part of Porsche’s Can-Am effort at its beginning. In fact, he was a competitor—for one race. In 1969, both parties joined the Canadian-American Challenge Cup series at its fifth round, Mid-Ohio. Donohue and his Roger Penske racing team immediately saw their customer-model Lola wasn’t going to be competitive against the McLaren factory’s all-conquering “Bruce and Denny Show,” and left to concentrate on venues where they could be successful, such as Trans-Am and Indianapolis.

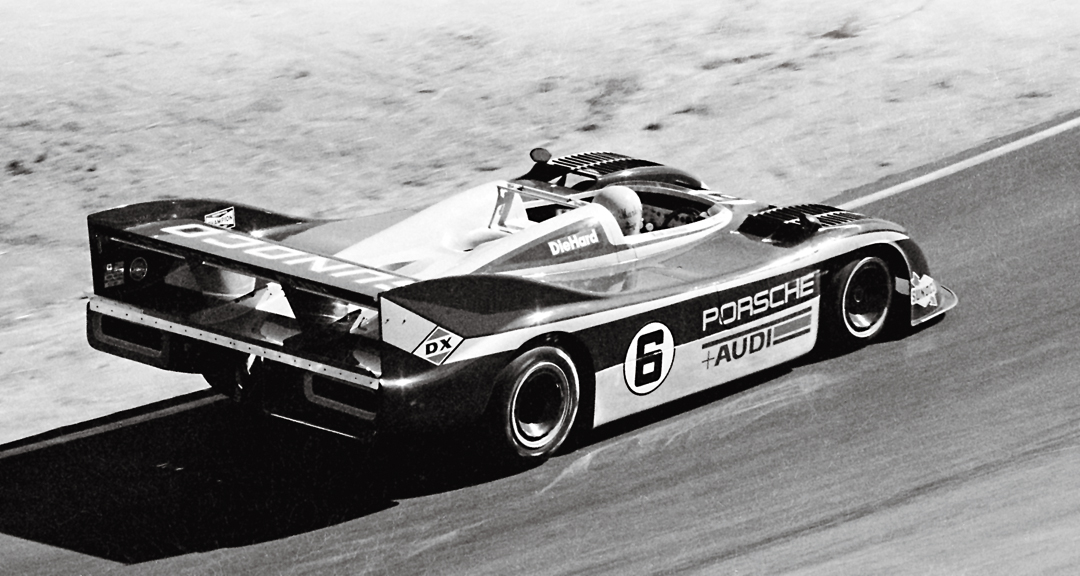

Jo Siffert and Porsche persevered with the Can-Am. The Swiss driver was heading a quasi-factory program that used a topless version of Stuttgart’s new 917 Le Mans coupe. As a Can-Am car, the 12-cylinder, 4.5-liter 917PA (for “Porsche+Audi”) Spyder was underpowered and overweight, but it was very reliable. Despite his late start, Siffert wound up the 11-race 1969 series 4th on points. Two years later, with an updated, 5.4-liter 917/10, he repeated that performance—despite tragically losing his life in an F1 crash just before the end of that 1971 Can-Am season.

By that point, Donohue and Penske were working behind the scenes with Porsche toward an all-out, factory-backed assault on the Can-Am for 1972 and beyond. Gaining more power was the primary concern. The Can-Am McLarens of the day had 8.3-liter Chevys making about 750 horsepower and 650 ft-lbs of torque. The best the 5.4-liter Porsche could muster fell short by almost 100 hp and 200 lb-ft.

Porsche did try the traditional Can-Am trick of adding displacement, testing an enormous opposed 16-cylinder, 7.2-liter engine. At some 880 claimed hp, it probably would have done the job. But the engineers were more intrigued by the challenge of turbocharging their familiar 12.

It really was a challenge. At that stage in history, we had seen a few turbocharged engines in road racing, but none had worked very well. They put out big power, but it was not controllable power. The problem was “throttle lag,” sluggish response to gas pedal input.

Porsche also had this problem at first. Twin-turbo 917 motors were making stupendous numbers on the dyno, upwards of 1,000 peak hp. But there was no bottom end. Shortly before the opening race of ’72, Roger Penske shocked his client by suggesting they’d better not go. Another shock was last-minute, hands-on intervention by an exasperated Donohue—traditionalist Europeans were not used to a mere driver playing a lead role in engineering.

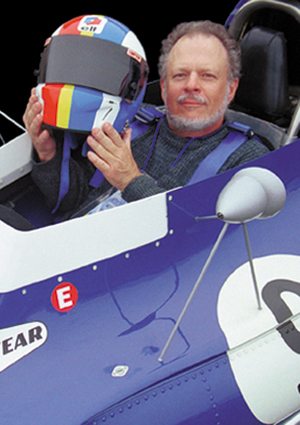

Of course, Mark Donohue was no mere driver. Holder of both an engineering and a business degree from Brown University, he was already renowned across North America for his brains and technical understanding, as well as his skill at the wheel. Ever since he began racing in 1958, he’d been developing his own cars, and he wasn’t about to let tradition shoulder him aside now.

In his great book The Unfair Advantage, co-written with Paul van Valkenburgh, Mark expressed great respect for Porsche’s engineers, facilities and expertise, but also described having to personally recalibrate the engine’s fuel system both on the dyno and on the test track until, “Suddenly, it was right!” He took the same aggressive stance to mold the car’s suspension geometries and aerodynamic profiles to his liking.

The Penske Porsche 917/10K (“K” for Kompressor, or turbocharger) did go to Mosport for the season’s first Can-Am, where it was so much faster than the McLarens it was immediately dubbed the Panzer, after a German military tank. Donohue started from pole and was easily leading that race—until a valve in the complex turbo system jammed.

Then, in testing before the second race, the rear bodywork came off and the car cartwheeled into a fence, seriously injuring Mark’s left knee. Penske called in George Follmer to substitute. Mark had to watch another man drive “his” car to its first victory and, ultimately, to the 1972 Can-Am championship.

In 1973, McLaren abandoned the Can-Am, leaving Penske without major opposition and forever making the Panzer known as the “car that killed the Can-Am.” Unrepentant, Donohue and Porsche worked relentlessly to make it faster, giving the redesignated 917/30 a longer wheelbase for more stability, new bodywork for more efficient aerodynamics, and even more power—nearly 1,200 hp. In testing, Donohue saw 240 mph on a long straightaway. Still, he only half-jokingly expressed his disappointment that there wasn’t enough power to spin his wheels the whole way along.

Photo: Pete Lyons – www.petelyons.com

After misadventures in the first two races of the ’73 season, Donohue dominated the last six and won the Can-Am championship by more than double the points earned by the next man, defending champ Follmer.

In his book, Mark described his pleasure in driving this perfected machine in his last race at Riverside, where he’d fitted an adjustable rear sway bar. “After I got way out in front, I began playing with the bar, turning it up to oversteer, and broadsliding the car around the tighter turns. I really had a good time sliding all over the place—knowing that I could rebalance the car at any time…”

On the victory podium, Mark Donohue announced his retirement.

“The best combination of man and machine that had ever appeared on a race track”; that’s what many people thought about what they’d seen that year.

Have we seen a better since?

Great article on Mark Donohue and the mighty 917. Bit disappointed you didn’t include my Australian hero, Sir Jack Brabham, in your list of drivers who founded their own car design and manufacture. He was instrumental in sorting the rear engined Coopers and then with Ron Tauranac went on to design and build very successful Brabhams in Formulaes 1 and 2 and remains the only man to win the world driver’s title in his own car.