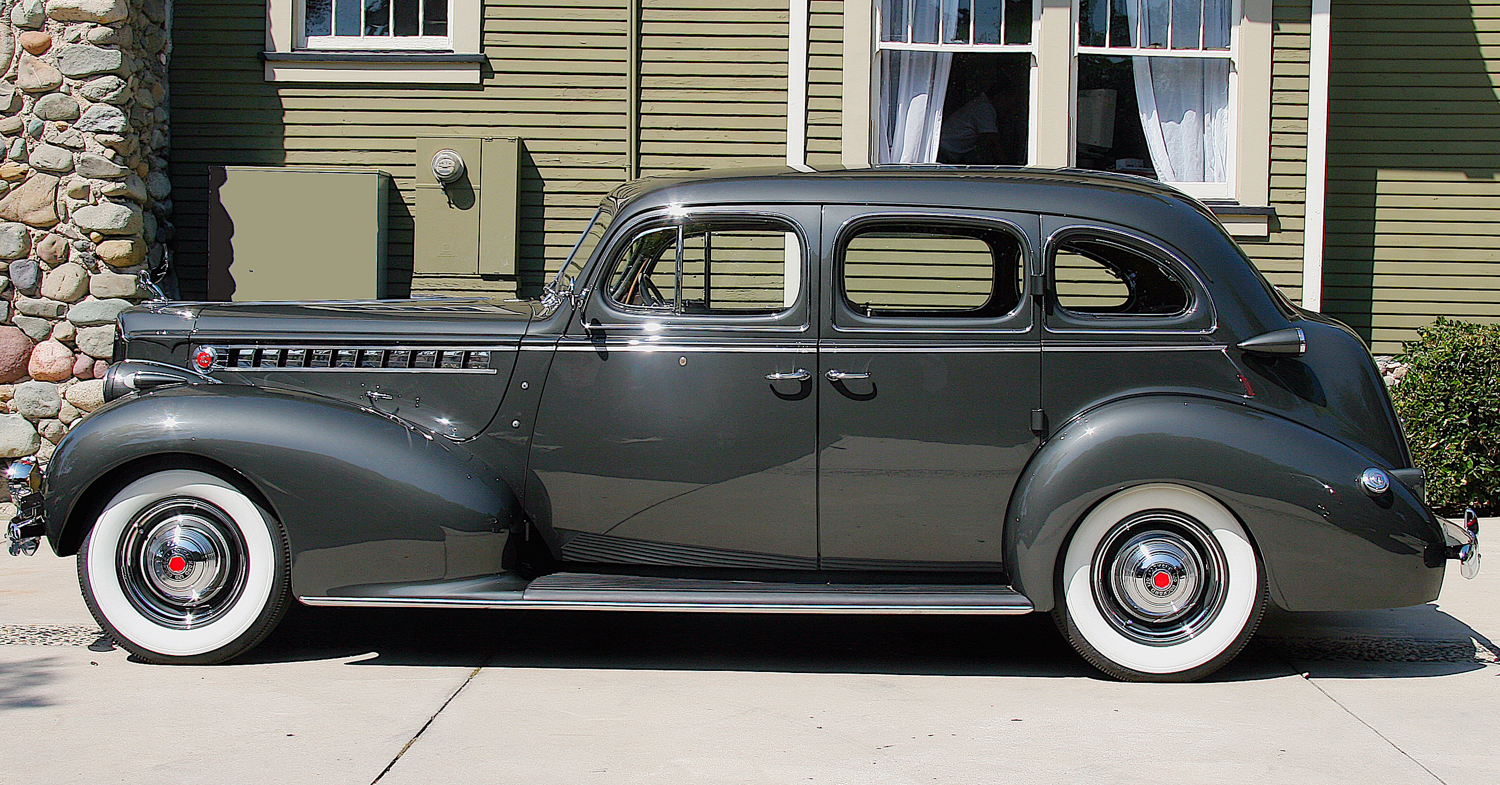

But this metallic Sea Cloud Gray 1940 120 touring sedan is impeccably restored down to the smallest detail, which is unique for a junior series four-door sedan. The time, expense and effort that went into Ed Stifel’s classic is usually only lavished on one-off customs and senior series Packards destined for Pebble Beach. But this was a labor of love.

Its original aspen wood graining is painstakingly matched. Its extremely rare factory air conditioning system is correct, even to the decals and hoses. It also has several other rare and sought-after options available that year, and its deluxe interior is spot on. Granted, it is not a Senior car, a convertible or a Woody— the most spectacular models of the genre — but the quality of the restoration is unsurpassed, as is the car’s understated elegance.

And all of this is the more interesting because the vehicle has been virtually recreated from what remained of a rusty, abandoned derelict that many would have considered a parts car at best. It only happened because, to owner Ed Stifel III of Triadelphia, West Virginia, this particular Packard was very special indeed. It was an automobile he had desired since childhood. It had belonged originally to his great uncle Henry “Dick” Gee, a prosperous electrical components dealer in Wheeling, West Virginia, who bought the car new in the spring of 1940.

Ed and his Packard happened to be in California for a tour and show, and the car was being preened at Escalante’s Custom Auto Service facility in Santa Ana. I was eager to see it and drive it, but time was of the essence. In fact, I needed to do it then and there, because the car and its owner were headed home to West Virginia the next day. So I dropped everything and drove to Escalante’s shop. We exchanged pleasantries and then we took the car to a quiet older area on the edge of town where it fit in and we could put it through its paces.

As one would expect of a well-maintained Packard, the engine comes to life instantly and settles into vibration-free silence. Head and legroom are abundant in the front, and absolutely lavish in the rear. The large round speedometer with a needle the size and shape of a medieval broadsword is flanked on either side by a full complement of easy-to-read analog gauges and there is a large clock in the glove compartment door that actually works.

The clutch pedal is as big as a playing card and its action is easy. The three-speed column shift is sure and smooth. I pull the car into low, give it a little throttle, and it silently oozes away like hot syrup on pancakes. Only an electric car is as quiet as a Packard in good order. Going down the drive and into the street is seamless, with no bump or vibration. Acceleration from the 282, inline, flathead-eight coupled to its Borg Warner electric overdrive (Packard called it Econo-Drive) is good, though if Ed’s uncle Dick had wanted swifter acceleration he could have opted for a more ostentatious 160 or 180 model with Packard’s then-new 356-cubic-inch Super Eight that made the senior Packards the fastest production cars available in 1940.

The 120’s center-point steering is very light and all the more surprising when you consider the car’s 3,800-pound weight. In fact, the 120’s steering is so effortless and well balanced that the British publication Motor, referring to its road test of a 1936 model with the same system, stated: “The steering, altogether rather low geared, is so exceedingly easy to operate that one can spin the wheel by engaging a forefinger with one of the spokes. Nevertheless, the steering remains quite steady at speed, has a nice self centering action, and does not convey road shocks back to the hands.” No doubt the example they tested was also equipped with the extra-cost, shock-absorbing banjo steering wheel, as is our 1940 120 series test car.

Braking is good, with very little nose-dive, and cornering is surprisingly flat for a car of the era thanks to Packard’s patented Saf-T-fleX independent front suspension, later copied by Roll-Royce, and also used on the Ford Bronco. The old touring sedan is well behaved and sure of itself even at freeway speeds of 60 to 70 miles an hour. The long, tall aristocratic hood, crowned with Packard’s optional cormorant ornament gives a feeling of majesty and elegance as we motor along in living room sofa comfort.

The car is tall by today’s standards, with no transmission hump in the floor, front or rear. As a result you look down on most modern traffic, which is as it should be, and are eye-to-eye only with the SUV crowd. But even with your eyes on the road you are aware of the admiring stares of those around you. Packards were the epitome of conservative good taste in their day. Turn signals, in the rear only, were an extra cost option for the first time in 1940, but very few cars were so equipped.

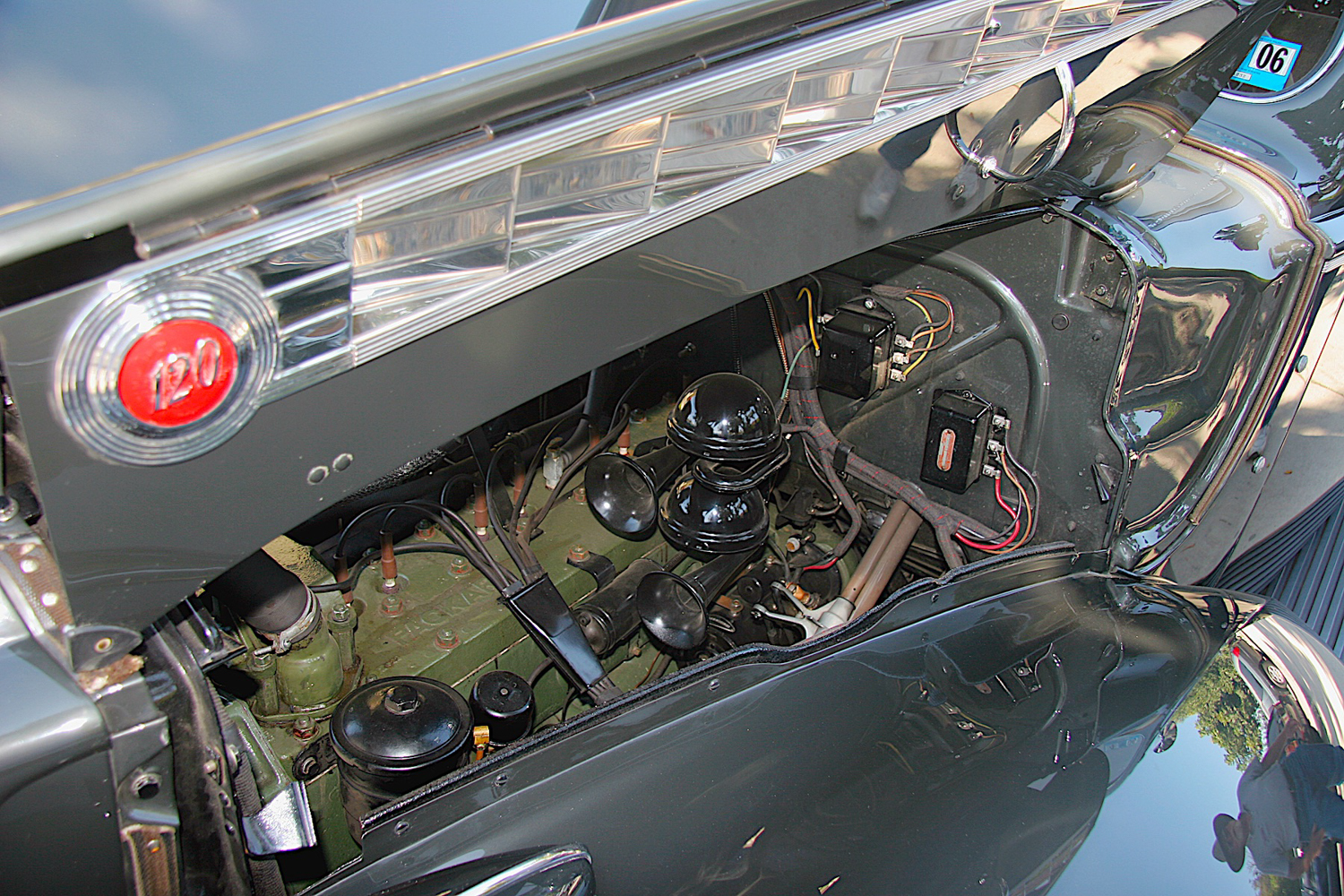

The factory-installed air conditioning— an industry first in 1940— is quiet and effective though a little draughty for those in the back seat because the cool air outlet is right behind the passengers’ necks, which was standard practice on air-conditioned cars for many years. Our test car is one of only five 120 models known to have been so equipped. At first, in late 1939, the Weather Conditioner as Packard called it, was offered on all models, but by the spring of 1940, installations were restricted to the Senior cars, making Ed Stifel’s touring sedan rare indeed.

And yes, air conditioning was available as an after-market add-on as far back as 1934 in the form of a large box that hung off the rear of the car on a luggage rack, but Packard was the first to integrate it into the design of the automobile. Cars destined to be equipped with a Weather Conditioner were sent to the Bishop and Babcock Manufacturing Company, in Cleveland, Ohio, to have it installed. Needless to say, at $310 depression era dollars, it was not a particularly popular option.

The compressor up front is the size of a BSA Gold Star motorcycle engine, and the rest of the paraphernalia for the system mostly consumes the trunk. It uses R12 refrigerant, piped through tubing the length of the chassis. A hand-operated damper controls the interior temperature. All told, Packard sold a bit over 1,500 air-conditioned cars before World War II.

And though it works well, it is not like a modern system. The compressor runs all the time because there is no clutch, so the faster you go, the cooler the car’s interior becomes, unless you divert the cold air out of the car. But the system also works as a heater just by actuating the lever inside that operates the damper. It is essentially the mother of all automotive climate control systems. Cadillac, which had been working on it for some time, followed suit with their own air conditioning in 1941. But such systems did not come into general use in most cars until the 1950s.

In the winter, the V-belt for the air conditioning compressor could be removed to save fuel and increase power, and the car’s conventional heater could still be employed as required. But in my experience, unless the weather is quite cold, the English wool broadcloth interior and the well-designed draft-free body will keep you pretty cozy in all but the most inclement weather.

Oldsmobile’s, and later, Cadillac’s, completely automatic Hydra-Matic transmission also debuted in 1940 and was so revolutionary that it was not to be equaled by the other car makers until nearly a decade later, but Packard did offer the aforementioned Borg Warner electric overdrive beginning in 1939 that gave you essentially five speeds forward, and you could shift without a clutch except when taking off from a standing start.

In 1941, Packard offered their Electromatic clutch that worked much like Volkswagen’s automatic stick shift, which worked well, though it was kind of a Rube Goldberg arrangement. With that setup you had an automatic clutch, but you still did the shifting. Packard finally came out with an automatic transmission called the Ultramatic, in 1949.

The 282, inline-eight in Ed’s 120 produces a lot of torque at low rpm, so the big car pulls from a stop pretty well, and the Econo-Drive overdrive makes it possible to cruise at modern freeway speeds with ease. But even though Packard 120 models with overdrive are capable of high speed driving, there are a couple of factors that might limit the prudent modern driver’s enthusiasm.

The first is the car’s brakes. Though excellent for the era, they cannot compare to the stopping power of modern, lighter cars with disk brakes. The other issue is that the wheels and tires of the heavy old Packard must be carefully balanced, because the car is softly sprung to achieve good ride. Any imbalance would make itself abundantly clear in the form of tire-destroying vibration at high speeds.

Back in the 1890s the Packard brothers, James Ward and William Dowd, owned a thriving electrical supply company in Warren Ohio. And legend has it that in 1898 they decided to buy themselves an automobile from the Winton Motor Carriage Company. However, it wasn’t long before the brothers became frustrated with their acquisition’s reliability, so they contacted Alexander Winton and explained the situation. The rather prickly Winton merely replied that if they thought they could build a better car they should do it… so they did.

In 1899, the Packard brothers founded the Ohio Automobile Company and began producing their own machines. They only built five cars that first year, but they produced and sold over 200 the next. In 1900, the company offered a well-designed vehicle with such industry firsts as a modern steering wheel and a taillight. Then in 1903 the firm was purchased by a group of investors, renamed the Packard Motor Car Company, and moved to Detroit where it flourished until the 1950s when it merged with Studebaker.

Early on, the rivalry with Winton was intense. In 1903, a fellow named Nelson Jackson and his mechanic Sewell Crocket were the first to cross the United States in a Winton in 64 days. Then hot on their heels Packard’s model F, called Old Pacific and piloted by E.T. Fetch, more than equaled the feat by taking a far more treacherous route and still beating Winton’s record by two days.

Cadillac dominated the luxury car market in the United States until 1925, but Packard’s main competition for the reputation of building the finest automobiles in America were Peerless and Pierce. And then later, during the classic era, Cadillac again became a major challenger for that honor just when the demand for fine, handcrafted automobiles all but disappeared in the 1930s. It was only in the 1940s that Packard began to concede the high ground to Cadillac, a situation that contributed to the legendary firm’s demise in the 1950s.

The great depression caused widespread unemployment and a virtual mass extinction of the luxury carmakers such as Deusenberg, Marmon, Pierce, Stutz, Cord, and Peerless. Cadillac only survived because it had General Motors’ huge share of the industry as a whole to fall back on. At first Packard’s product line in the early ’30s was aimed exclusively at the carriage trade too.

But management knew that if the company were to survive, they would have to broaden their range of products to appeal to the less affluent. Their first attempt at doing so was the 1932 Light Eight, which was a handsome smaller Packard, but it too was built largely by hand in the traditional, painstaking manner. As a result, Packard lost money on every one they produced. It was then that the company’s leaders knew they had no choice but to go to mass production.

So, betting the firm’s future and its remaining fortune in a do-or-die gamble, the leadership at Packard built a multi-million dollar modern factory on East Grand Boulevard in Detroit with a state of the art assembly line, and grabbed experts wherever they could find them, including from General Motors and more specifically Pontiac, to help design their new car.

The result was the model 120, which made its debut in 1935. It was smaller, lighter and less opulently equipped than the big hand-crafted senior models. And because it was mass-produced on a moving assembly line, Packard was able to sell the car for under a thousand dollars, making it competitive with Oldsmobile, DeSoto and Buick.

The 120 was a solid, well engineered and well appointed automobile that carried the Packard name proudly, and it had many of the elegant styling cues of the prestigious Super Eights and Twelves, but on a more diminutive scale. It was an instant success. Over 10,000 of them were sold sight-unseen before the 120 even made its debut at the New York auto show in January 1935. It trounced Cadillac’s smaller, sportier LaSalle in sales, and even gave Buick a run for its money. Of course a major reason the 120 was such a hit was because of the Packard Motor Company’s superlative reputation.

The company was successful in turning their fortunes around, but they did not rest on their laurels. For 1936, the 120’s 257-cubic-inch, 110 horsepower inline-eight was enlarged to 282-cubic-inches to produce 120 horsepower, and it rode on a 120-inch wheelbase, hence the 120 designation. And then, for 1938, the whole line of cars was redesigned, suspension was improved, and the 120 chassis was lengthened to a 127-inch wheelbase. During 1938 and ’39 the car was merely called the Packard Eight. However, the 120 designation was again used in 1940 through the 1941-’42 series.

The 120 model’s Wagner-Lockheed hydraulic brakes were excellent, its new suspension system the best in the industry, and its striking traditional Packard ox-yoke grille distinctive. (Incidentally, the so-called ox-yoke grille was actually patterned after an English gothic church window to counter Rolls-Royce’s Greek Parthenon radiator shroud.)

The new mass-produced 120—and in 1937 the introduction of the even less expensive 245-cubic-inch, six-cylinder powered 115— saved Packard from the sad fate of most of the other prestige automakers, as well as many mid-priced makes such as Hupmobile, Graham, Reo and other independents of the depression era. In fact, while these companies were failing, Packard enjoyed its best year ever in 1937.

A recession hit in 1938 so nobody sold a lot of cars that year. But 1939 and ’40 were again good years for Packard, as the country began to emerge from the long depression. In fact they did so well that in 1940 Packard had dropped their twelve-cylinder engine and replaced it with their big new 356-cubic-inch Super Eight in their senior 160 and 180 models, and all Packards were built on the assembly line, so profits were excellent.

Packard did very well during the war years too, building Rolls-Royce Merlin engines under license and actually out-producing Rolls considerably. In fact, they emerged from the war debt-free. But sadly, during the late ’40s and early ’50s the company was not able to adapt to the changing times. And then an ill-advised merger with ailing Studebaker spelled the end for the venerable old automaker. The last real Packards emerged from the Grand Boulevard plant in 1956. After that there were a few re-badged Studebakers built with the Packard nameplate, but even the name was dropped in 1958.

So what motivated owner Ed Stifel to restore his Packard to Pebble Beach standards? I asked him that, and he said: “My childhood friends and I frequently rode our bikes around Uncle Dick’s semi-circular driveway at his home, passing that beautiful Packard, which was usually parked out back beneath the large porte-cochere, and we marveled at its stately elegance and classic beauty. It was then I determined that one day I would own such a regal automobile.”

Stifel kept track of the car over the years, but it wasn’t until 20 years ago that he was in a position to obtain and restore the old Packard. “Years before it had been parked down in a hollow near a stream and covered with a plastic tarp. It was rusty, not running, full of holes, dull, cracked and broken. You’d need a tetanus shot just to go near it. But in July of 2000 my dream as a young boy on a bike was fulfilled and I acquired the car.”

Local experts told him it was too far gone to restore, but he didn’t give up. “In the fall of 2000 Cook Enterprises of Erlanger, Kentucky, began the body work. Classic and Exotic services in Troy, Michigan, took on the engine and running gear. And Classic Air Conditioning in Tampa, Florida, restored the air conditioning.”

Ed says: “The car is a joy to drive. Steady, responsive, comfortable and dependable. It’s lovely in its lines and never fails to attract admiring attention from all who view it. I know Uncle Dick, wherever he is, smiles once more when he thinks of his beloved Packard.”

And today, thanks to Ed Stifel’s determination and Herculean effort, I am able to experience for a brief time what it was like to own and drive one of the cars Packard built during their halcyon days. Back when their understated, stylish, quiet, comfortable and reliable cars were still the masters of the road. I imagine Ed’s Uncle Dick would be pleased to see his cherished Packard restored to such impeccable standards after all these years.

SPECIFICATIONS: 1940 PACKARD 120

| Price | $2,250 including air conditioning and accessories such as rare factory prototype directional signals |

| Production | 28,269 (all 120 models) |

| Engine | Inline eight cylinder |

| Displacement | 282.1 cubic inches |

| Bore | 3 1/4″ |

| Stroke | 4 1/4″ |

| Horsepower | 120 @ 1,800 |

| Max torque @ rpm | 225@2,000 |

| Compression ratio | 6.41 |

| Valve configuration | Valve in block |

| Valve lifters | Mechanical |

| Fuel system | Stromberg EE-16 two-barrel downdraft carburetor |

| Lubrication | Full pressure |

| Cooling | Centrifugal pump |

| Exhaust system | Single |

| Electrical | 6-volt |

| Transmission | Three-speed standard with Borg Warner overdrive |

| Rear axle | 4.09 |

| Steering | Worm and roller |

| Ratio | 20.19 |

| Turning circle | 42.6 Feet |

| Brakes | 4-wheel internal hydraulic |

| Drum diameter | 12” |

| Chassis and Body | |

| Construction | Body on box girder chassis |

| Suspension | |

| Front | Independent, Double A arm, Coil springs, Shock absorbers |

| Rear | Solid axle semi-elliptic leaf springs |

| Shock absorbers | Delco double acting |

| Wheels | Pressed steel |

| Tires | 7.00 x 16″ |

| Height | 65″ |

| Wheelbase | 127″ |

| Length | 202.21″ |

| Front tread | 59″ |

| Rear tread | 60″ |

| Weight | 3,800 |

| Crankcase | 5 quarts |

| Cooling system | 18 quarts |

| Fuel tank | 21 gallons |