Turns out it was also an entry at Pebble, and its owner had driven it there rather than having it trailered in the usual manner. I chatted with him, and asked him how fast he had been going. He replied that he kept it at around 80 mph on the long straightaways, and that its 490 cubic inch engine wasn’t even working hard. I learned later that the Marmon V16 was capable of 106 miles per hour, so I suppose it wasn’t.

The classic Marmon V16 was the company’s finest— and final— hour, but more on that later. The styling of these magnificent automobiles is unique, restrained, and truly beautiful. They were designed by Walter Dorwin Teague Junior, son of the famous industrial designer and architect of the same name.

The Cadillacs, Packards and other luxury cars of the era were styled to reflect the classical themes you see in the architecture of the early 20th century, with banks and government buildings looking like Greek Parthenons, and in the case of the Packards, grilles that echo the English Gothic tri-foil church window.

Every aspect of the V16, from the hubcaps to the hood ornament (that replaced the standard radiator cap), to the car’s lines in general, carries out this sleek clean geometric theme, making for a very handsome distinctive and understated look. From the first time I saw a classic Marmon V16, I vowed to drive one some day and indulge myself in such exquisite luxury if only for a few moments.

That’s why, recently, we went to my friend Gary Severn’s collection in Southern California. He graciously consented to let us drive and photograph his 1932 Marmon V16 coupe – which is the subject of this report. Gary has a superb private collection of true classics restored to show winning grandeur.

Severns leaves no detail unaddressed to make his cars as correct and original as possible, and his 1932 Marmon V16 coupe is no exception. He actually had new aluminum heads cast for both of his Marmon V16s because the old ones had deteriorated to a rather sad condition. And while he was at it he made several more so other Marmon owners could keep their cars on the road as well.

The engine in Gary’s coupe is as detailed and pristine as the rest of the car, and looks like the inside of a Swiss watch, just as it would have been when it left the factory. You see, back when this car was created, all of the fine hand-built luxury cars were detailed this way. Less expensive mass-produced cars had painted engines, but the great classics had polished aluminum, brass and chrome detailing along with porcelain-coated manifolds.

After coffee and the usual how do you do’s, Gary pulls his stunning coupe out of the garage, and we jump in and head to a local park for a photo session. The Marmon’s big substantial door swings wide to allow easy entry, and closes with a solid “chunk” sound. The seat is as comfortable as the easy chairs at the Princeton Alumni Club in New York. There is plenty of head, leg and shoulder room. And the dash is very form-follows-function, much like that of an airplane, with a full array of big easy to read analog gauges. The interior even smells sumptuously of old leather.

I know the engine is running despite the fact that I hear and feel nothing. There is no vibration at all. I depress the smooth multi-disk clutch and pull the tall floor shifter into low gear. As I pull away I gently ease down on the gas pedal. I realize that I am using a small portion of the car’s 390 foot-pounds of torque to get going. In its day, many V16 Marmon owners simply started out in second gear and never shifted except when they were out on the open road and wanted to do over 60 mph.

The Marmon shifts smoothly and silently thanks to its big General Motors Muncie three-speed transmission, which has synchromesh in second and high gear. In high gear, at the speed limit of 65 mph, the engine is loafing along. This is vastly different than the cars the average person drove in the early ’30s that were all in at around 50 mph.

The car can actually do 70 in second gear. Amazingly, the Marmon V16 could even out accelerate the mighty Duesenburg Model J, though the Duesy had a higher top end. Of course, the combination of incredible torque, and a rather tall for the time— 3.69:1 rear end—plus the use of a lot of lightweight aluminum construction throughout, and a very light flywheel helps make this kind of performance possible.

Steering takes a little effort, but is not like most big cars of the era that steer like log trucks. The Marmon’s vacuum assisted Bendix mechanical brakes with wide 16-inch drums are more than adequate, take little effort to apply, and show no signs of fade. That’s no doubt because Howard Marmon, who engineered the car, had a lot of experience with racing, and knew that stopping was as important as going.

Bumps are discretely implied in the big Marmon thanks to precision ball bearings at each of the spring eyes. As we motor along, lesser vehicles hustle and bustle around us, doing what ever it is ordinary people do, but in our Marmon we motor along quietly and serenely, ensconced in an automobile designed to make other cars absorb the damage from a collision.

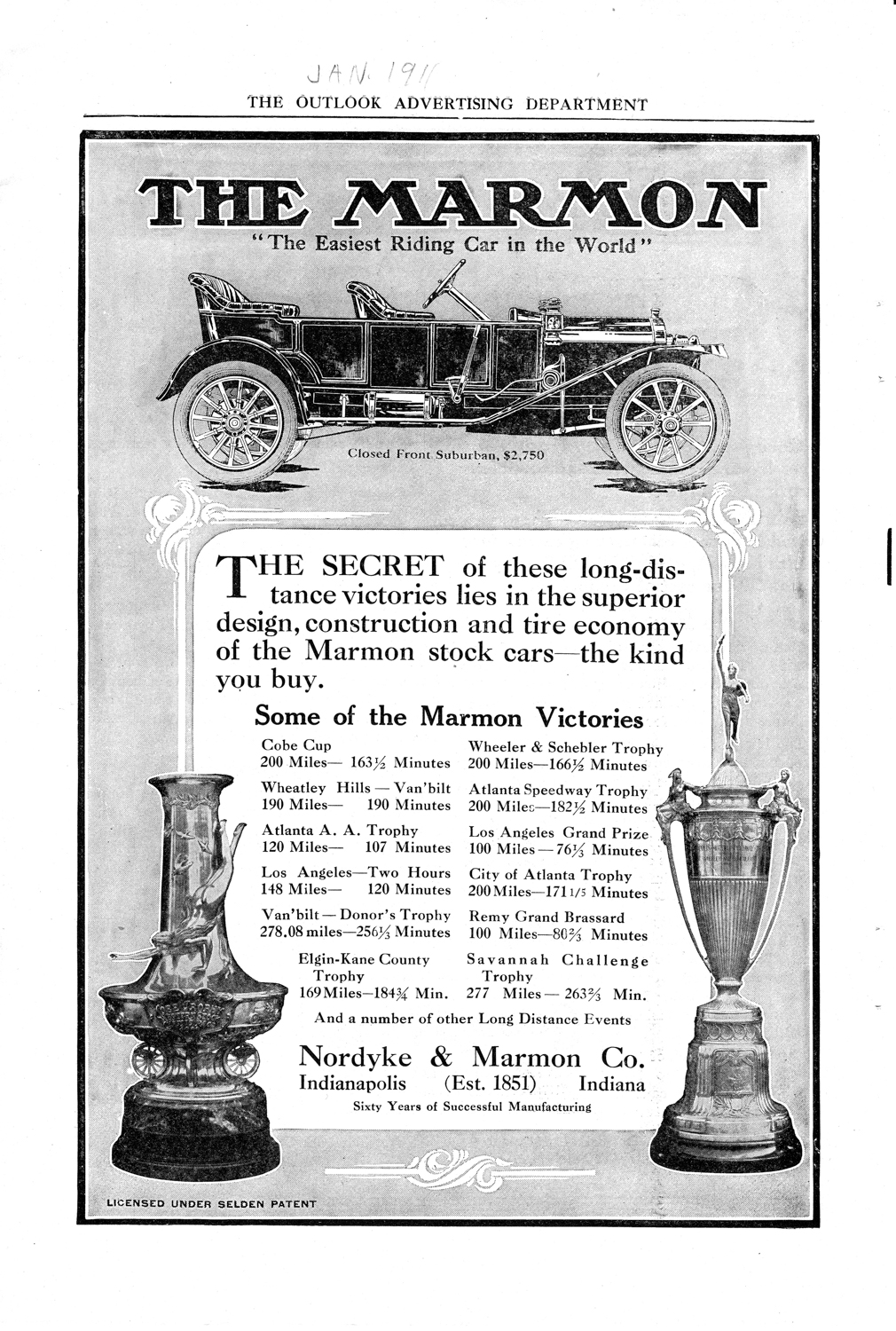

The Marmon Motor Company grew out of the Nordyke Marmon Company, in Indianapolis, Indiana, a manufacturer of flourmills founded in 1851. Brothers Howard and Walter Marmon, the sons of owner Daniel Marmon, became interested in building automobiles around 1900, and created their first car at the company works in 1902. Howard had studied engineering at Stanford University in California and he became chief designer, while Walter managed the finances. Their goal was simple. They wanted to build the ultimate motorcar.

Howard’s initial endeavor was an engine that produced 20 horsepower. It was an air-cooled, overhead valve, 90-degree V4 configuration. Production got going in 1904 with the Marmon Model A, a car that sold for $1,600 dollars, which may not sound like much now, but amounted to $43,313 in today’s money. They sold five of them in 1905.

And then, in 1906, Marmon came out with their patented double three-point suspension. The company’s advertising shows a Marmon chassis with one wheel jacked up a foot above the other three wheels, but with the others sitting upright on the ground. Raising one wheel did not tilt the other axle, making for much better handling and traction on the rudimentary roads of the era. And that was thanks to a pivoting sub-frame for the rear wheels. This was a revolutionary design for the time and a forerunner to independent suspension.

The 1906 model had a 90-inch wheelbase and sold for $2,500. The company sold 25 of them that year. They also developed later in 1906 their Model 37 which was a seven passenger touring car with a 128-inch wheelbase that sold for $5,000 and was powered by an enormous 707 cubic inch, air-cooled V8 that made 65 horsepower. However, even with its huge power plant it only weighed a mere 3,500 pounds thanks to the extensive use of aluminum in its construction.

The M37 was not a success, so Marmon went to a more typical water-cooled inline four-cylinder engine in 1909, along with a more powerful six they called the Model 32. And just as it is now, it became obvious, even in those pioneering days, that racing on Sunday sold cars on Monday, so Marmon modified one Model 32 for racing, and that was the none other than the Wasp that won the inaugural Indy 500 in 1911. Actually, in all, Marmon racked up 51 racing triumphs between 1909 and 1912.

Motor racing historians know the name Marmon because Ray Harroun won the inaugural Indianapolis 500 in 1911 in a yellow Marmon Wasp equipped with an enormous 9.8-liter, T-head six-cylinder engine. The car still exists today, and is in the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Museum.

Back then the cars had to qualify at a speed of 75 miles per hour, and sustain it for 25 miles. Just finishing the race was considered impressive because it proved reliability. No other race in the world went 500 miles at that time. Indy was an endurance race back then, and the pits were just that, pits in the ground, so mechanics could get under the cars to work on them. The starting order was determined by pulling the names out of a hat, not by qualifying speed.

Harroun was able to win because he was driving a superbly engineered car designed around a technological breakthrough for its time – I’m talking about the rear view mirror. Some say Harroun invented it. Up until then it was considered mandatory to take a ride-along mechanic with you to warn of upcoming traffic, but thanks to the mirror, Harroun’s entry could be made narrower and lighter than other entries. And when it comes to the mirror, Marmon didn’t mess around. It was 5” by 8” and mounted on the cowl with big steel straps to hold it in place. Never the less, Harroun said it was all but useless due to the vibration emanating from the brick track. But the rear view mirror made it possible for the Wasp to be the first single-seat Indy car.

Harroun won, not by driving fast, but by running at a steady 75 mph for the whole race. His team had determined that driving faster than that meant a lot more tire wear, and by taking it easy Harroun made it with just four pit stops, when others were stopping twice as often and risking terrible crashes. And this was back when men were men and drove with no helmets, roll bars or seat belts. In fact, the strategy in a crash was to jump from the car to avoid being crushed by it.

One Model 34, driven by a relay team, made the trip from New York to San Francisco in only five days, breaking Cannonball Baker’s record driving a Cadillac by a surprising 41 hours, and this was long before there was an interstate highway system. Sales more than tripled after that.

Marmon introduced new high-end prestige models for 1924 to replace the Model 34, but then the company ran into financial trouble, and in 1926 was reorganized as the Marmon Motor Car Co. Under pressure from creditors, General Motors veteran George Williams was named president of the company, replacing Walter Marmon, Howard Marmon’s brother.

In 1929, Marmon came out with an inline-eight powered car called the Roosevelt that sold for under $1,000, but it came too late to help the company recover, and the stock market crash of 1929 made things even worse. Also, though Howard Marmon had begun working on the world’s first V16 engine in 1927, they were unable to go into production with the sixteen until 1931. By then Cadillac had been marketing their own V16 for a year, stealing Marmon’s thunder.

The 1930–1933 Marmons were mechanical masterpieces, and their magnificent V16 engines were unequalled. That is to a great degree because the other two contemporary American V16 engines were essentially knock-offs of the Marmon. Cadillac lured away Owen Nacker, Marmon’s chief engineer in 1927 in order to create their own V16, which was clearly influenced by Marmon’s initial design, as was the Peerless prototype which was built with the help of James A Bohanon, who had been Howard Marmon’s purchasing agent for 6 years.

So why did Marmon go to 16 cylinders you may ask? The answer, other than prestige, was that with the low octane fuel of the era, they couldn’t get a complete burn across a large diameter combustion chamber with more than about 4.5:1 compression. If the compression were any higher, the fuel would detonate and ruin the pistons. Many earlier cars had huge pistons, but their compression ratios were low, and they often used twin sparkplugs for each cylinder.

One way around the detonation problem of low octane fuel was to add more cylinders and decrease the bore diameter. Adding cylinders also made for a smoother engine, with a broader useable RPM band. And with 16 cylinders arranged in a 45-degree V, Marmon ended up with a velvety smooth motor with so much bottom end torque that you could simply put the car in second gear to start off, and drive all day without shifting unless you went out on the highway.

Of course, going to more cylinders had its downside too. The first being complexity. Machining required for such engines was extensive and expensive. Also, such engines necessitated a lot of moving parts, which made for more friction and inertia to overcome, resulting in some loss of power.

In the 1920s, Howard Marmon was inspired to create a V16 to top Packard’s legendary twin-six for his ultimate automobile. And what he finally came up with was truly the best of the best. The aluminum block and crankcase was cast as a monobloc, as was the crankcase. Steel sleeves were then inserted for the cylinders.

Marmon also used aluminum cross-flow heads, with two valves per cylinder and a modern intake manifold in the center of the Vee with a single two-barrel downdraft carburetor. Cadillac employed overhead valves, but with reverse flow cast iron heads, and obsolete updraft carburetors mounted on separate manifolds on either side of the engine.

The Marmon’s connecting rods were the older fork-and-blade configuration in order to cut down on engine length and weight. But, unfortunately, development at Marmon took until 1930. The result though, was an engine that weighed a mere 900 pounds, with a displacement of 490.8 cubic inches, making 200 horsepower.

Cadillac’s V16 was much heavier at 1,300 pounds, and its output was only 175 horsepower to Marmon’s 200. Cadillac used more modern side-by-side connecting rods, making for a simpler but longer engine too. However, Cadillac was able to beat Marmon to the punch, debuting their V16 in 1929 and capturing much of the rapidly diminishing market for such high-end luxury cars before the depression took hold.

As magnificent as Marmon’s V16 cars were, they came out too late. It had seemed in the late ’20s that prosperity would never end, and that the demand for fine motorcars would continue unabated, but it was not to be. In fact, Cadillac only survived because it was part of behemoth General Motors, and Packard kept going because they took a gamble and started making mass-produced, less costly offerings.

Peerless, Pierce, Cord and a number of other prestige makes soon went under due to the virtual extinction of the carriage trade. The V16 powered cars had come in an era when there was a vast difference between the least and most expensive cars.

Slowly over the next two decades, the low priced Fords, Chevrolets and Plymouths became more comfortable, durable and stylish cars, and the extravagant hand-built custom cars died out in favor of more luxurious albeit mass-produced Packards, Cadillacs and Lincolns.

Today, the fine custom luxury car market is essentially gone, with the exception of Rolls-Royce. Instead, absurdly fast supercars occupy the top rung of the automotive prestige ladder. That is, unless you are a guy like Gary Severns, who collects and restores those that still survive from an earlier epoch. Severns also has a stunning 1932 Marmon V16 sedan in his collection that he painstakingly restored, and that has been invited to Pebble Beach, along with his Packards, Cadillacs, and Lincolns from the golden age.

We cruise silently back to Gary’s shop, nodding to passers by and enjoying the comfort and class of this rare and magnificent machine. For a few moments we were living like the aristocracy, even though I was dressed more like a gardener. If I only had a million or two in the bank that was not doing anything I could have one of these, but as it is I can only dream.

SPECIFICATIONS

Engine: 45-degree V-16, ohv, aluminum alloy block, 490.8 cid (3.125 × 4.00-in. bore × stroke), 200 bhp @ 3,400 rpm, 380-400 lbs/ft torque (est.)

Transmission: 3-speed selective, synchronized on 2nd & 3rd

Suspension: Rigid axles, semi-elliptic springs, 2-way hydraulic shock absorbers

Brakes: Duo-Servo with vacuum booster, 16-in. drums, 353.75 sq. in. effective area

Wheelbase (in.): 145

Tires: 7.00 × 18

Weight (lbs): 5,090-5,480, depending on body style

Top speed (mph): 106

Acceleration 5-60 mph (sec): 20 seconds

*Production: est. 390 total