It’s a simple fact that the most popular form of motor racing in Australia today is sedan racing. Of course, this is much to the chagrin of the purist who would walk over hot coals to watch open-wheelers or sports racing cars. It was quite the opposite during the 1960s when the cream of the Northern Hemisphere’s drivers would travel south to escape the northern winter for the Tasman Series. Spectators in the thousands would flock to circuits to watch such names as Clark, Hill, Brabham and McLaren behind the wheel of almost new Grand Prix cars from the likes of Ferrari, Brabham, Cooper and BRM.

However, 1960 brought the start of an event that has grown substantially over the years and would come to dominate Australian motor racing through to the present day.

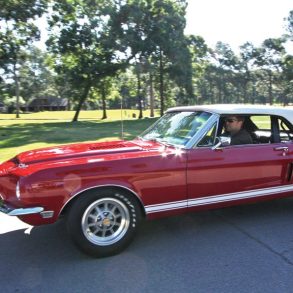

Photo: Steve Oom

Phillip Island, in the Australian state of Victoria, is almost as far south as you can go on mainland Australia before you reach the ocean. Then and now it is famed for its Fairy Penguins, holiday atmosphere, sheltered beaches, swimming, surfing and, of course, the picturesque Phillip Island Grand Prix Circuit where motor racing has been held continuously since 1928. It is a track that from its front straight, drivers probably have a better panoramic view of the coastline and ocean than anywhere else on the island.

Motor racing now and in the 1960s, is an excellent way of showing off your products to prospective customers. That was certainly on the mind of the managing director of shock absorber manufacturer Armstrong York Engineering when he agreed to sponsor a 500-mile endurance race for Australian-built or assembled production sedans at Phillip Island. Called the Armstrong 500 it consisted of five separate classes divided according to engine capacity. Class A was up to 750-cc with such cars as the Renault 750. From there to 1300-cc was Class B, which included the Simca Aronde and Volkswagen Beetle. The Peugeot 403 fit into Class C for 1301-cc to 2000-cc. Class D (2001-cc to 3500-cc) included the Ford Falcon and Mercedes-Benz 220SE. The final class (E, over 3500-cc) attracted a single entry, an Australian-assembled Ford Customline.

There was no outright winner, as the laurel wreaths went to winners of each class. However, as happens, history does record that the first car to reach 500-miles was a Vauxhall Cresta driven by John Roxburgh and Frank Coad.

Change

The Armstrong 500 returned to the Island the following year, but there was a change to the structure of the classes. Instead of five classes there were now four, but still tied to cubic capacity and slightly reshuffled. In Class A, or cars with an engine capacity over 2,600-cc, were the Vauxhall Velux, Ford Customline and a new kid on the block—a Studebaker Lark entered by the Canada Cycle and Motor Company, the assemblers of Studebakers in Australia.

Despite being powered by a smaller capacity engine, the first to 500-miles was a Mercedes-Benz 200SE driven by Bob Jane and Harry Firth.

The classes changed again for 1962, but instead of being tied to engine capacity they were now based on the retail price on the showroom floor! This meant that Class A were those cars that sold between £1251 and £2000 and included the Citroen ID19, Chrysler Valiant and Studebaker Lark, but as happens, history records the first car across the line as the Ford Falcon, again driven by Jane and Firth. The Ford was in Class B (£1,051 to £1,250) with the Studebaker of Fred Sutherland and Bill Graetz finishing on the same lap.

Bathurst

Three years of sedan racing was hard on the surface of the Phillip Island circuit, so much so that it was breaking up in places. So, after a considerable amount of lobbying by the Australian Racing Drivers Club, in conjunction with the Bathurst local council, the Armstrong 500 moved 575-miles north to the Mount Panorama circuit, which is in the Australian state of New South Wales.

By 1963, the stature of the Armstrong 500 had risen considerably with the race being the first Holden vs. Ford confrontation—an ongoing battle, even today. Not only were there factory entries from Ford, BMC and Chrysler, but also a myriad of other entries from private competitors and also from the likes of the Canada Cycle and Motor Company. A works Ford Cortina 500 led across the line, which was the first of the cars built with one aim in mind—to win at Bathurst.

Now known as the Bathurst 500, the classes of this annual race continued to be tied to the sales price of the cars through to 1973 (also the last year before the distance was metricized to the Bathurst 1000 as it remains today). The event is now part of the V8 Supercars Championship, and continues to be a Holden versus Ford race, although the last few years have seen works entries from Mercedes-Benz, Nissan and Volvo.

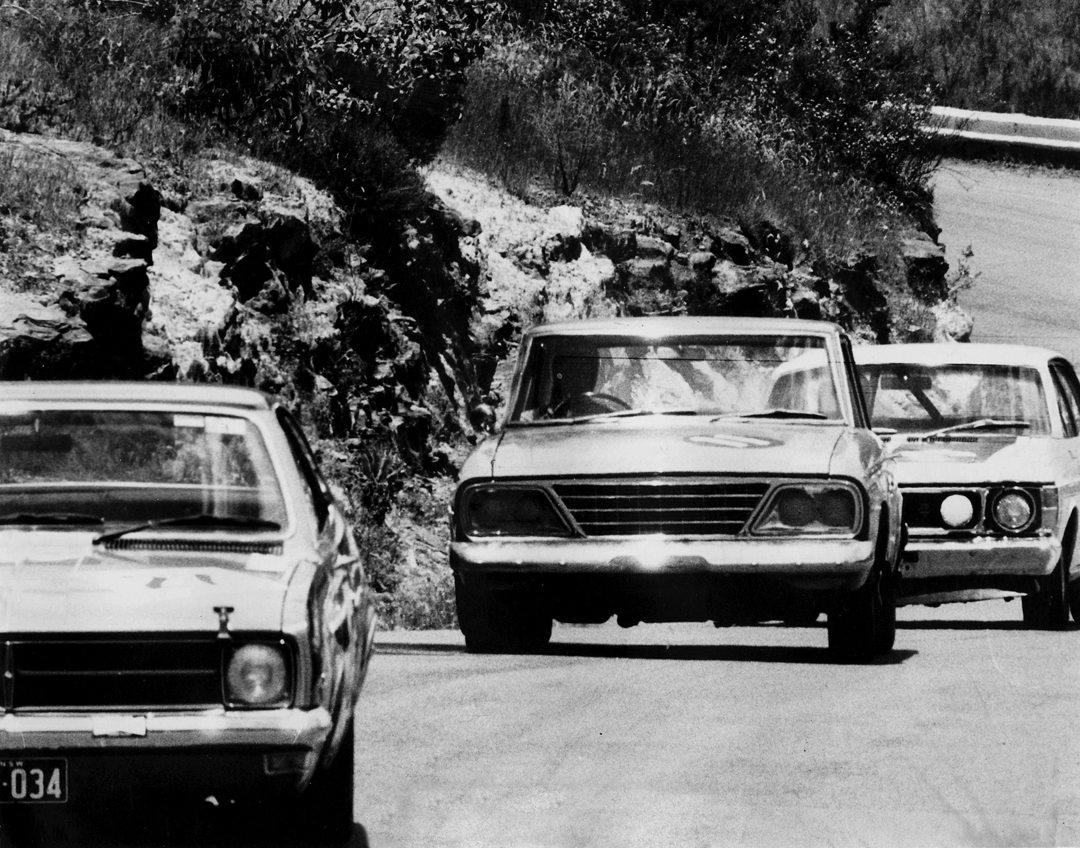

Photo: Steve Oom

Studebaker Downunder

As in the U.S., the history of Studebaker in Australia predates the introduction of the automobile with horse-drawn buggies and wagons being imported toward the end of the 19th Century. Scant records indicate that Studebaker vehicles were also imported in the early years of the 20th Century and when Australian soldiers returned from WWI they spoke with respect of the quality of Studebaker gun and troop carriers. The 1920s brought an escalation of Studebaker sales, along with that of the Erskine that were made with export in mind.

The ’20s through to the start of the Second World War could not have been said to be hugely successful for the marque in Australia. For the Australian market, any Studebaker was seen as a large car and not cheap, partly due to a hefty duty imposed on any imported motor vehicle. By the mid-1930s, fewer than 1,000 examples were being sold here during any year. However, after the hostilities, sales picked up, mainly due to a government edict to support vehicles manufactured in Britain or its member Commonwealth countries. This included cars imported from Canada that attracted a lower import duty than those from the U.S. It wasn’t just Studebaker that took advantage of this, as quite a number of U.S.-designed marques were imported into Australia via Canadian subsidiaries.

Historically, what was a large car in Australia was a medium-size car in the U.S., so when Studebaker released the compact “Lark” in 1959 it suited the Australian buyers perfectly. Here was a car that was large by our standards, but under the bonnet was a V8—something almost unheard of in Australia unless you wanted a U.S.-sized, large car like a Chrysler Royale or Ford Fairlane. Australian-built cars of the period were either four- or six-cylinder.

So buoyant were Studebaker sales in Australia after the release of the Lark that the company decided to introduce local assembly in Melbourne using CKD kits from Canada. The company to do this was the Canada Cycle and Motor Company that had been in operation since the 1920s and distributed such diverse marques as Renault, Talbot, Russell, Darracq, BSA, Humber and Standard.

The performance of the Studebaker Lark did not go unnoticed in a number of quarters, particularly the various state police forces that used the model as pursuit vehicles or for use by the higher echelon. It was also noticed by the motor racing enthusiast.

Photo: Steve Oom

Racing Studebakers

There are records showing that, in Australia, Studebakers were being used in competition events as early as 1930, especially in hillclimbs. However, it wasn’t until the early 1960s when the attributes of such models as the Lark became really noticed.

As mentioned the local police took to the Lark, as did racing enthusiasts. Speed was, of course, the reason and despite being a large car by Australian standards, it was perfect for our racing conditions as when it came to V8-powered cars there was virtually no opposition.

Focussing purely on the Armstrong 500, there were Studebakers entered from 1961 through to 1968. With entries being a mix of private, dealer and semi-works in the case of the Canada Cycle and Motor Company. While the Studebakers were never first across the line, they did achieve class wins on three occasions and numerous high class placings. Remember, at this time, technically there were no outright winners, just class placings. However, 50-plus years on, the car/drivers that covered the 500-miles first are those remembered the most.

Around the Mountain

The Mount Panorama circuit could be best described as commanding. Located just outside the inland city of Bathurst, which is roughly 130 miles from Sydney, the most populous city in Australia, Mount Panorama has been in use as a motor racing circuit since 1938. So popular was that first race meeting that the shops of Bathurst were almost denuded of supplies for days afterward by the spectators, but worse still it took close to a week before fresh beer supplies could reach the town!

The circuit was and still is not for the faint-hearted with its steep climbs, over the horizon turns and a breathtaking downhill and undulating main straight. Mount Panorama is just on four miles in length with a vertical difference between the lowest and highest point of 570-feet. However, like so many of the world’s great circuits it remains an enigma. Apart from race days anyone can drive around the circuit at any time and at any speed, providing you don’t exceed the speed limit of 60 kph or 37 mph. Yes apart from race days, practice and so on, the Mount Panorama circuit is a public road, and is officially defined as a Scenic Road.

Located at the end of Murray’s Corner, just before Pitt Straight is the National Motor Racing Museum, which houses a plethora of both cars and motorcycles that have played their part in Australia’s motor racing history.

One of these cars is the 1964 Studebaker Commander that was run in the Armstrong 500 of both 1967 and 1968. Thankfully, the car is in excellent condition and as you will see it does have an interesting history, especially in the earlier days of its life.

A Bathurst Studebaker

The car is now owned by Rick Marks, who besides being an avid collector of historic vehicles also has a family history in Studebakers.

“My family was always interested in Studebakers,” Rick commented. “My father had a 1953 Studebaker Champion that he bought in 1954 which was worth a lot of money back in those days. It was really his dream car. I got interested in Studebakers in the early 1970s and bought a Silver Hawk and a Champion, so I guess that it was a little bit in the blood.

“As far as the Commander goes, it really comes down to its Bathurst history that got me interested. Over the years I have been fortunate to have quite a few historic racecars, but never one with a Bathurst history, but the thought of owning one has always appealed to me. When this came up as both a Studebaker and ex-Bathurst, it sort of all gelled together. The car was in a collection in Perth and when it came up for sale I decided to buy it.

“Studebakers, including this one, were assembled in Melbourne by the Canada Cycle and Motor Company. It came to Australia in CKD and put together in police specifications, because its first life was as a vehicle for the Victorian Police Commissioner. While it was an official police car, it was still built as a pursuit car. All the police cars were fitted with 289-cid Studebaker V8 engines, manual gearboxes, lowered, heavy-duty suspension and a larger fuel tank. All Australian-delivered Studebakers were built right-hand drive in Canada before being shipped CKD. They were using V8 Studebakers in the Victorian and New South Wales police and other states for some years, as they were the only V8-powered car available.

“The original color of the car was Sea Light Green,” Rick continued. “Most of the police cars were in a light blue and we could never quite work out why this car was in green, but we found out that it was ordered that way for the Commissioner to be different to the other cars. You could understand that in that guise it had a fairly quiet life until it was later bought by Bert Needham, the New South Wales Studebaker agent who had been racing Studebakers at Bathurst since 1963. Bert bought the car at the police auction and kept it for himself. He bought the car because of it being a two-door and therefore the lightest available, with the 1967 Bathurst race specifically in mind.”

Australian V8s

“At the time it was virtually the only car available with a V8 engine,” Rick added. “There may have been a Chrysler Royal or Customline, but they were hardly suitable for racing. The Studebaker was certainly the package with its comparative light, compact body and V8 engine. The cars were also quite successful in their time and would qualify well, even on pole position, and would easily have the fastest top speed down Conrod Straight, but they did have a couple of Achilles heels, in the brakes and wheels. The four-wheel drums just weren’t up to the racing conditions and the wheels would crack and break up.

“The car ran at Bathurst in 1967 and ’68, and before that Needham ran the heavier four-door Studebaker. In 1967, he knew that he had competition in the form of the new Ford Falcon XR GT, hence the lighter Commander. Interestingly, he used to baby the car and people I have spoken to have said that they saw it in his showroom with the boot and doors ajar, so as to not squash the rubber seals. Even today the car just has 33,000 miles on the clock.

“In 1967 the car ran with the production 289 engine with a Borg-Warner T10 4-speed manual gearbox, while originally it would have had a 3-speed floor shift. It was driven by Warren Weldon and John Hall. Sadly, Warren is no longer with us, but John has been very helpful with his recollections. The car currently has the livery from the ’67 race where it finished 11th outright and 3rd in class behind the two XR GT Falcons. While it recorded a forward position on the grid and an impressive speed down the straight, it was just outclassed by other cars, especially the much newer Falcons and Alfa Romeos.

“The car ran again in ’68,” Rick added. “It was far more liveried up for that race, but that was the year of the new Holden Monaro HK Monaro 327. History tells us that the Monaros did very well at winning, while the Studebaker came in 13th outright and 7th in class. Other cars in the class were the much newer and faster Ford Falcons and Monaros. In that year, it was entered as a 1965 car as it wouldn’t have been able to run as a ’64 car, for being out of date. Of importance was that as a ’65 car it was allowed the 4-speed gearbox that it already had, plus front wheel disc brakes.

“Not long back I put it to John Hall that it must have been a cumbersome car to drive, but he said that it was one of the best. John also said that it was a myth that the Studebakers were plagued with problems while the only real difficulties they had were with the brakes and wheels. Mechanically they were as strong as any other on the circuit.

“After Bathurst Bert decided to run the car in improved production events,” Rick said. “This was probably the only place for it at the time, as Bathurst was restricted to production cars. So Bert imported a R4 Studebaker Avanti engine from the U.S. that had been built up by Andy Granatelli, who was with Studebaker while also heading up STP. These engines were quite different in their specifications with such high-performance components like the pistons, rods, heads and so on. It came into Australia as a crate engine complete with twin four-barrel carburetors and like this Bert fitted it to the car. Bert then ran the car at circuits such as Catalina Park in the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. Bert’s wife Meg also ran it at the Castlereagh drag strip, where she managed 13.1-secondss for the quarter-mile. After that Bert used the car on the road and kept it on display in his Sydney showroom.”

Tragic

“Bert Needham owned the car right through to his death in 1980,” Rick noted. “His death was at best described as tragic as it came about from working on the car. He was preparing it on a Saturday to take it to a Studebaker Club concours the following day. While tuning the twin four-barrels, he was leaning over toward the carbs when the radiator fan disintegrated and struck him in the head. Unfortunately, while his injuries were very serious, it was as a result of infection that he died in April 1980.

“Bert’s wife Meg, not long after, was approached by a Studebaker enthusiast in Melbourne to sell the car, which she did. He kept it for a few years before selling it off to the owner of a small museum south of Melbourne. From about 1985 through to 1994 it changed hands a few times while receiving an engine rebuild and some minor bodywork repairs before heading west to the new owner in Perth, on the other side of Australia. He had a Studebaker Avanti with an R4 engine and I am sure the attraction to him was having another car with the same engine. The R4 engine is very rare indeed and it’s thought that there are just 10 left in the world today and accordingly are worth quite a lot. Studebaker engines all carried the ‘R’ prefix from the R1 through to the R5. The only one that came originally to Australia was the R1, which was the naturally aspirated 289 V8 that the Commander had when new, while the R4 was a different capacity of 304.5-cid with all the high-performance components. They were very strong and powerful engines for their day, but nothing compared with modern engines.

“I bought the car in April 2012 after it was advertised in the Studebaker Club web site and a few commercial sales sites and publications. I had been looking at Studebakers and thinking that at some time I might buy one. Then I saw this car, which was going for a lot more money than I wanted to pay, but I thought about it and its history, and decided that it would be good to add to my collection of high-performance and historic racecars. I ended up buying it sight unseen, and when it arrived I was the happiest I have ever been with any car I have ever bought as it was exactly as described.”

Livery

“When it arrived it was finished in its original color,” Rick said. “As it was a genuine Bathurst car I wanted it in the livery of one of the two years it raced there. I decided to do the livery on the car as how it ran in 1967 and first showed it at a special tribute day for Warren Weldon not long after his death. I’m pleased with how it turned out, but I did make a big mistake. The only photos I had were black and white, so all the stickers I did were in white, when I have since found out that they should have been yellow.

“What the photos showed was that the exhaust exited from the side so I changed that, which has also made it sound fruitier. Apart from that, all I have done is to maintain and service the car. I don’t know for sure if the paint is original as I do know that in the late 1980s the then owner did undertake some sympathetic bodywork on the car. Apart from that, the trim is original as is everything else. I put that down to how Bert Needham kept the car during his ownership. As mentioned it doesn’t have a huge number of miles on the clock, and I have spoken to all the past owners, except for Bert, and none of them drove the car very much at all.

“I took the car up to the Museum in Bathurst after they expressed some interest in having it on display along with other Bathurst event cars. I ran it last year at the annual Muscle Car Masters where it was the oldest genuine Bathurst car in attendance. It’s been here at the museum ever since and it would probably stay here for as long as they want it. I don’t intend to race it, just preserve it as the historic competition car that it is.”

At Speed?

We arrived at the National Motor Racing Museum at the foot of Mount Panorama and, thanks to the kind staff of the museum, the Studebaker has been pushed to the exit door. A little further and it’s out in the mid-winter sunshine. After installing a fresh battery the car starts after a few turns of the starter and quickly settles down to a pleasant rumble.

Sitting behind the wheel takes me straight back to the 1960s, and I’m surprised to see a tachometer among the instruments, just as surprised at the Astor push-button AM radio—both unusual additions to any car available in Australia during the 1960s.

However, it all looks straightforward to me, so after strapping on the lap seat belt we head toward the top of the mountain and the best corners. Remember apart from when it’s a racing circuit, Mount Panorama is a public road and speed is restricted. You exceed it at your peril as the circuit is a favorite stalking place for the local constabulary.

So we fly up the hill at less than race pace, but even at these lower speeds it’s easy to understand that with the skinny tires and steering wheel the car would have been a handful, especially with the smooth vinyl bench seat! I had previously been looking at the S-shape gearshift, but soon found out that it really did suit the car.

The Studebaker does have a wonderful V8 burble that rises considerably with the revs, and the gear change is a delight. The brakes are excellent, and even at our lower speeds it’s reassuring to touch the pedal slightly when approaching Skyline, where the road drops away quickly to the right and all you can see are the farmlands in the far away distance. How wonderful it would be to let it fully stretch its legs down Conrod Straight, but I suspect that the tailing Ford, complete with officer, may have wanted a quiet word. Besides, by keeping my speed down I wasn’t doing anything wrong, nor is the wearing of an open-face helmet illegal. Don’t know about photographer Steve lying prostrate in the middle of the road taking the photos, though.

The Bathurst downhill esses, just following Skyline are a delight, and how exciting it would be at racing speeds with the skinny tires of the period allowing the car to slide controllably. At our test pace the corners are easy, but it doesn’t take much of an imagination to realize what it could be like. While Conrod Straight today is a pale image of what it was like in the ’60s, modern racecars can still easily reach 300 kph, or just over 185 mph. A little bit faster than the Studebaker, but back then cars and drivers had to cope with not only a much longer straight, but also a crest where cars of the period would lift off, causing very light steering and susceptibility to crosswinds.

I liked the Studebaker Commander as it’s from a period of Australian racing before the big players really entered the fray. A period prior to when the V8 was king. An honest car that was ready for the circuit back then without the need of much in the way of preparation. It drove well, handled well and sounded great. Thank you to Rick Marks and the staff at the National Motor Racing Museum for making it readily available.

[button link=”https://dev.sportscardigest.com//product-category/subscriptions/” color=”red”]Like this article? Subscribers have access to over 8,000 more just like it. Click here and subscribe for as low as $3/month.[/button]

Specifications:

Chassis/Body: Unified steel chassis and body

Wheelbase: 109 inches (2,768-mm)

Track: Front 57.4-inches (1,457 mm) Rear 48.5 inches (1,232 mm)

Weight: 2,695 pounds (1,225-kilograms)

Suspension: Front: Independent with coilover shock absorbers, anti-roll bar Rear: Rigid axle with leaf springs Dana 44 LSD 3.54:1

Steering Gear: Saginaw manual steering box

Engine: 304.5-cubic inch Studebaker R4 (Fitted late 1968)

Compression Ratio: 12:1

Power: 280 bhp @ 4,500 rpm. 340-lb-ft torque @ 3,000 rpm

Carburettor: 2 X 4 barrel downdraught Carter AFB

Clutch: Single plate

Gearbox: Borg Warner T10 alloy-cased 4-speed close-ratio (fitted 1967)

Gears: 4 forward, 1 reverse.

Foot Brake: Front discs/rear drums (Discs fitted mid 1968)

Hand Brake: Under dash

Wheels: 5.5 x 15 inch front and rear

Tires: 7.35 x 15 front and rear