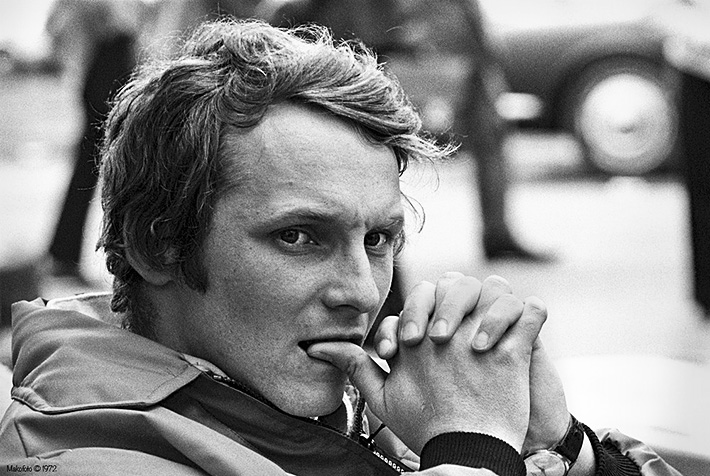

Niki Lauda Biography

Andreas Nikolaus Lauda was born to a well-to-do Vienna family on February 22, 1949. His family’s social status proved both nuisance and good fortune. Although he was later to become successful in business on his own, it was obvious early on that he was not cut to fit the conventional Lauda mold, much to his family’s consternation. He did, however, find a mansion bet sign up offer and the family connections to be useful when it later became necessary for him to borrow to support his racing. Lauda became interested in motor racing not from attendance at events or boyhood idolization of racing heroes, but rather from an innate interest in automobiles dating to a young age. When he was twelve, visiting relatives were letting him park their cars. He got hold of, in his early teens, a 1949 Volkswagen Beetle convertible in which he would ride roughshod over a relative’s estate. He entered his first race, a hill climb, in a Cooper in 1968 taking second in class. Thereafter, despite his father’s insistence that he stay away from racing, he competed in hill climbs and later Formula Vee. He did his stint hauling a Formula 3 car on a trailer to races around Europe. In the course of this he scared himself into a certain amount of sanity, and, in 1971, abandoned the wildness of Formula 3 to take the plunge on his own in Formula 2.

He squirmed out of his contract with Stanley, and was off on an often-rocky ride with Ferrari to two world championships. In 1974, his first year with Prancing Horse, Lauda scored the first of his 26 F1 victories. He, as well as teammate Clay Regazzoni, with good cars under them, challenged for the championship. Lauda took it in his second year with the team in a car that was technically far superior to any of the competition. He had 5 wins and a huge margin over second place. He called 1975 “the unbelievable year.”

This six weeks covered 2 races and saw Hunt draw close. The Brands Hatch win was given back to him on appeal, and he won at Zandvoort. Lauda’s return to competition at Monza produced an amazing 4th place and 3 points. Hunt scored wins in both North American races, while Lauda had to settle for no points at Canada by virtue of suspension problems, and a third at Watkins Glen. This impressive run pulled Hunt to within 3 points of Lauda with only Fuji left on the calendar. The race started in a monumental downpour, and after 2 laps Lauda abandoned saying it was crazy to drive in such conditions. He was probably correct, but he was probably also still affected by his Nurburgring accident. In the event, the rain soon slacked, and Hunt finished third despite a late tire change, collecting 4 points to take the title.

In 1977 Lauda cruised to his second championship despite winning only 3 races, then promptly dropped Ferrari at Canada. The parting was not amicable, although Lauda was later to recant much of his criticism of the team (and eventually serve it as a sort of minister without portfolio). He was apparently an example of that rare individual who was not over-awed by Enzo Ferrari. He claims to have regularly simply shown himself into The Drake’s inner sanctum when he wanted a word with him. And he was not cowed when those words became heated as tended to be the case following Fuji.

“What struck me was how ‘clever’ his best performances were. He often kept himself back, in practice, and awaited the right moment, and then really went flat out. He always thought more deeply than the others, and he also gave himself endless trouble preparing the race.” Fritz Indra, Ferrari Technician

Lauda returned to F1 in 1982 for, by his own admission, financial reasons. The fledgling airline that he had started (he loved flying so why not an airline; to Niki Lauda it made perfect sense) had fallen on hard times. He signed up with Ron Dennis and McLaren to partner John Watson for plenty of money (albeit, on only a 4 race contract to start with) and the promise of a competitive ride. Lauda’s comeback got tangled up in the great FISA – FOCA war. One of the more prominent skirmishes in this ugly affair occurred at the 1982 South African GP. Lauda wound up in the middle of a labor fracas before he had even turned a Goodyear in anger. The so-called Super License for F1 drivers had been introduced by FISA in an effort to keep marginal talents out of the cockpit. Owner members of FOCA (with the apparent connivance of FISA), however, had taken advantage of the licensing process to try and bind drivers to their teams. Most drivers, including Lauda with his shrewd eye for all matters fiscal, saw through this ruse and refused to sign. At South Africa they were threatened by FISA with being banned from the race for lack of licenses. Lauda and Didier Pironi, head of the Grand Prix Drivers Association, organized a resistance movement, and got most of the drivers to lock themselves together in a hotel meeting room over night while Pironi negotiated with FISA major-domo Jean-Marie Balestre. Balestre made concessions prior to the weekend having to be completely written off, and Lauda went on to place 4th in his first race back.

And it didn’t take long for him to reacquaint himself with winning. At Long Beach he won in only his third race since returning. He also won at Brands Hatch that season. ’83 was a no win year while the TAG Turbo was shaken down, but ’84 ended with Lauda back at the top of F1. Although he won the ’84 championship by a mere 1/2 pt., he seemed to have the measure of his usually faster rival and new teammate, Alain Prost, for most of the season. As quick as Prost was and as good a politician as he was, he met his match in the imposing personalities of Lauda and later Ayrton Senna. Lauda was seldom faster than the best of his rivals. He disliked risks that he considered unnecessary. He was not noted for redoubling his efforts when things weren’t going well. He was not one for making selfless sacrifices for the good of the team (though he would do so for the good of Lauda). He did often have good cars, but he also often had talented teammates who had the same cars – Regazzoni, Reutemann and Prost. One might wonder how it was that he was so successful. Lauda had the sort of self-confidence usually reserved for megalomaniacs, minus the psychosis. All three of his championships probably came about as much because he willed them into existence as for any other reason.

Another part was sheer smarts. Lauda, though a poor student as a youngster, is obviously possessed of superior intelligence in a branch of sport where that is saying a great deal indeed. This served him well off the track as well as on. He and collaborators have produced 4 very informative books on racing and his career (which, by the way, thoroughly dispel the notion that he was nothing but a cold-hearted machine). He mastered English quickly (and, per force, Italian while he was with Ferrari), and thus had a language other than German in which to deliver the patented Lauda interviews. These were dispensed with a combination of succinctness, authority and deadly aim that rivaled the Almighty handing down the Ten Commandments on Sinai.

“This year (1974) I wasn’t ready to become world champion. If I have a good season next year, I shall know the reason for it all: to make me tough and ready for great things”. Lauda

Lauda did not hang around long after taking his third championship. His second and final departure from F1, at Adelaide in 1985, was typical of his whole approach to racing and to life – quick, with no frills and no glance over the shoulder. One moment he was flying his McLaren down the long straight. The next his front brakes had failed him and he was skittering into the runoff area and up against the wall. The next after that he was out of his car disappearing behind the barrier without a look back and with the next flight out on his mind.

He was vigilant and not the least bit sentimental when it came to making money from racing, to the point of insisting on handsome payment for autograph sessions. These and other personal traits chafed some egos along the way. In his Ferrari days Lauda, the very antithesis of the Italian persona, never captured the love of the tifosi the way that Gilles Villeneuve, or even Mansell did. Yet he became a bona fide legend in his own time. Certainly part of this was due to his Nurburgring accident. But primarily it was a result of the unique impact that his personality and skills had on the sport. There may have been a few better than him, but there have never been any like him.

People who worry about paying their car payment or Titlemax title loan on time may find Lauda’s actions hard to understand, especially if they think race car drivers are overpaid. Whatever his monetary motivations, there’s no denying his skill behind the wheel.

“My PR value alone is worth that much. You’ll be paying only one dollar for my driving ability, all the rest is for my personality.” Lauda, during negotiations with McLaren and Marlboro to return to F1