I have admired Tazio Nuvolari all my life and so has just about every other motor racing enthusiast of my generation. My friend Murray Walker, the British television Formula One commentator, often likes to say he saw the Flying Mantuan race, but I was born too late to enjoy such a spectacle. So I did the next best thing: I read everything I could about the diminutive Italian.

But in spite of all that reading, one thing remained a mystery to me: the gold tortoise that became Nuvolari’s trademark.

Of course, I knew the Italian poet and dramatist Gabriele D’Annunzio gave a little gold tortoise to the driver, but that’s all. I did not know how a man from a totally different world (literary and political) came into contact with the motor racing star. Or the significance of a gold tortoise to D’Annunzio. Or whether the one he gave Nuvolari was a one-off, a kind of heirloom. Or why he gave one to the fastest man on four wheels in the first place.

For years, those questions nagged away at me every time I came across Nuvolari’s name, but I was always too busy to track down the answers. Then my friend and ex-Lancia world rally championship co-driver the late Maurizio Perissinot, who knew of my admiration for Tazio Nuvolari, gave me a small golden tortoise with the initials TN on its back. The tables had been turned: a racer (Perissinot) giving a writer (Newman) a small golden tortoise.

Right, I thought. I’m going to sniff out the answers to those questions once and for all. And I did.

Gabriele D’Annunzio (1867-1938) was an Italian superstar, an internationally famous dramatist and poet of the ’20s and ’30s. He was also a fervent nationalist and the commander, a rank by which he was known to many, of his own private army of black shirts. He even led a successful military attack on Rijeka, a town in north west Yugoslavia, which he believed belonged to Italy: but after taking the town he was ordered to surrender it.

D’Annunzio also loved tortoises, to the point that he would often weigh his own instincts and inclinations against those of the prudent, slothful little beasts and act accordingly.

The writer grew fond of tortoises when he was a child; he raised two of them from babies in the garden of his family home and loved them like others love their pet dogs. The two eventually died: the years slipped by until 1924, when D’Annunzio received a curt telegram from one of his rather bossy lady friends, the Marchioness Coré Luisa Casati Stampa. It said:

Hamburg, April 1924

You will receive a tortoise from Hagenbeck: put it in your garden.

Coré

Eventually, a huge tortoise arrived at D’Annunzio’s palatial manor, called Il Vittoriale, on the banks of Italy’s Lake Garda: the playwright was beside himself with joy. He promptly released the big lumbering reptile so that it could roam his large garden and took great pleasure in watching it go about its business. But the new arrival was not a well tortoise and died soon afterwards of what the vet described as “tubular indigestion”; the Commander was grief stricken.

In memory of his pet the poet D’Annunzio wrote to Renzo Brozzi, an expert in casting animals in precious metals, and asked the jeweller to cast the soft parts of the big tortoise (head, legs, tail) in bronze, which was done. Sometime later, the dead tortoise’s shell and the bronze castings came together and the result, measuring a massive 31 x 14 inches, became the centrepiece of the huge dining table at Il Vittoriale.

That, plus the two tortoises the Commander had raised as a boy, gave him an idea: he would share his love of the shelled ones with others. So he took to presenting his friends and prominent people with either small solid gold, gold-plated or silver tortoises as a mark of his esteem or friendship or both. According to my investigation, the poet went through well over 100 of the expensive little beasts; the first two, history records, went to Il Duce Benito Mussolini, leader of the black shirts and Hitler’s Fascist friend, who later brought Italy to its knees.

And that opened the floodgates, so to speak. D’Annunzio ordered another batch of little gold tortoises, in 1928. A couple of years later, he wrote and asked Brozzi to make him still more, but this time so that they could be worn as pendants. Two years after that, the poet asked the proprietor of a Milan jewellery shop, Mario Bucellati, to make him more with this letter:

15, February 1932

Dear Mario

Thank you for your note and for the exquisite objects, in particular the small tortoises. I would like many more; around fifty.

Gabriele D’Annunzio

This tortoise giving became such a regular occurrence that some people thought D’Annunzio had his own resident goldsmith working away at Il Vittoriale sculpting the little fellows.

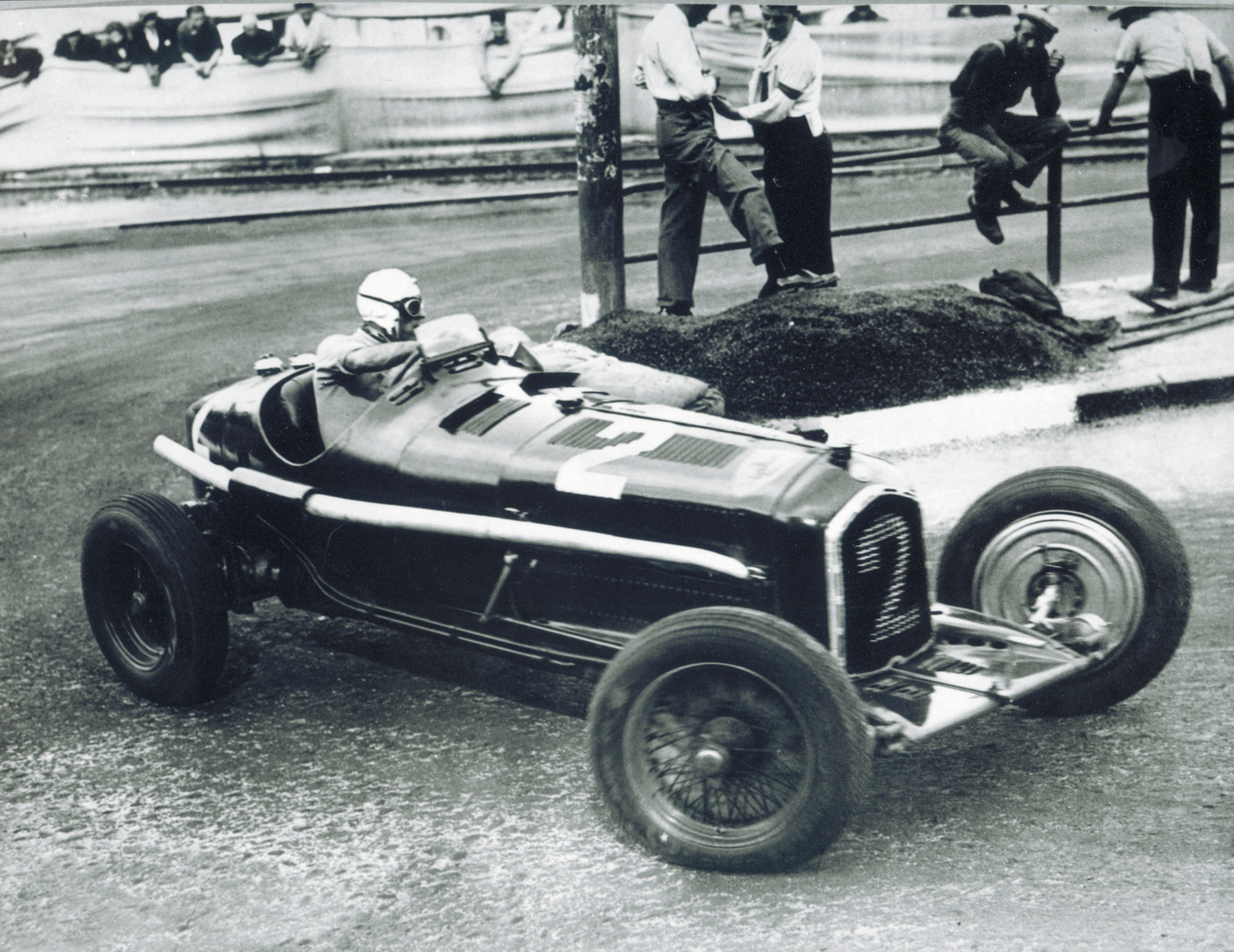

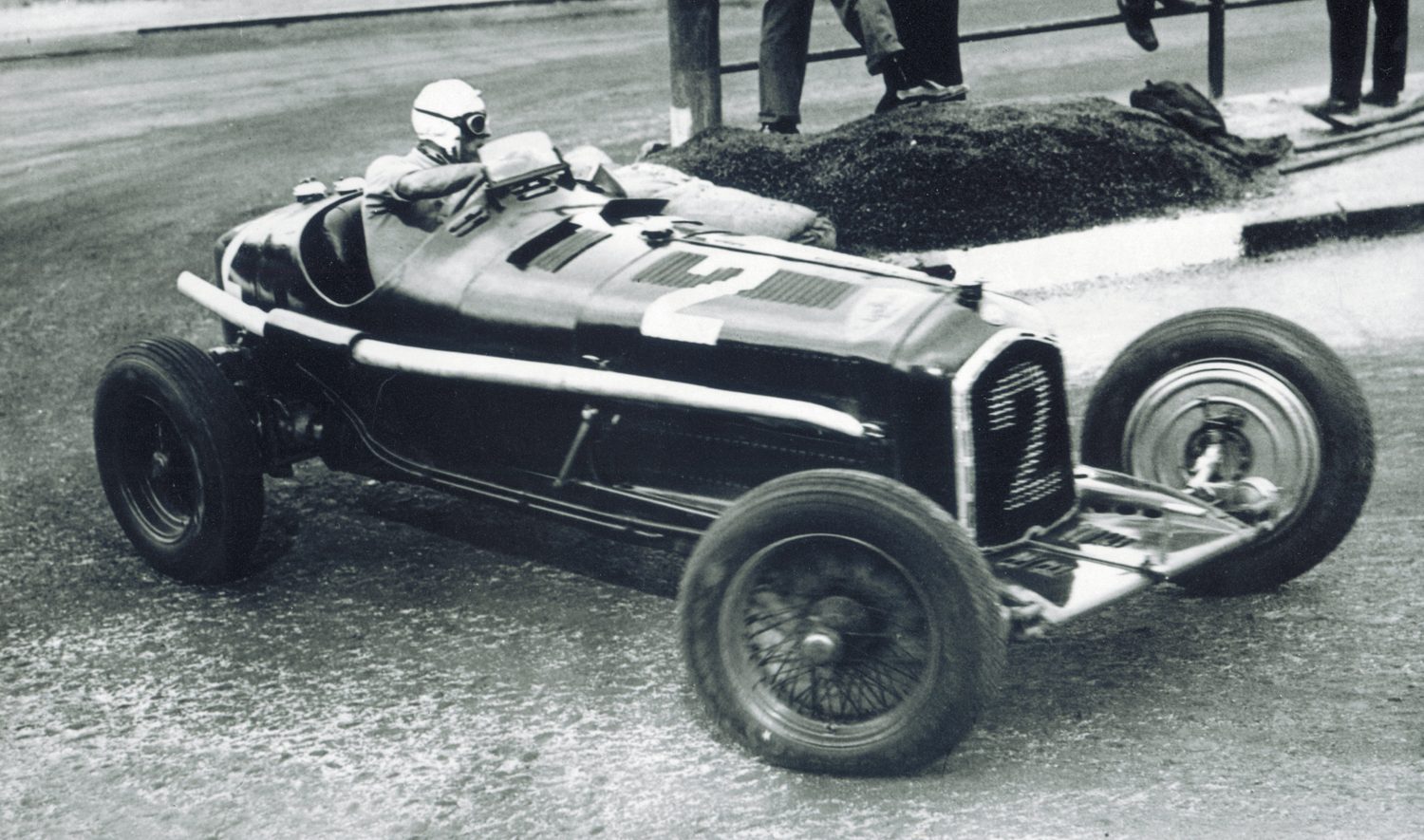

The effervescent Commander was always on the lookout for new excitement, new experiences, and when he heard that Nuvolari had won the Grand Prix of Monaco, in an Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 Monza on April 17, 1932, the playwright felt he had to meet this son of the wind, as the Italian press had taken to calling the driver. So D’Annunzio immediately wired the chief executive of Alfa, Prospero Gianferrari, and invited him and Nuvolari to lunch which, the writer being a national icon, thrilled the Alfa boss no end and he accepted. Not slow in realizing the PR advantages of a national hero being seen driving his product, Gianferrari also decided to present the poet with a brand new Alfa Romeo Berlina 6C 1750, which was joyously received, not least because D’Annunzio was experiencing a slight cash flow problem at the time.

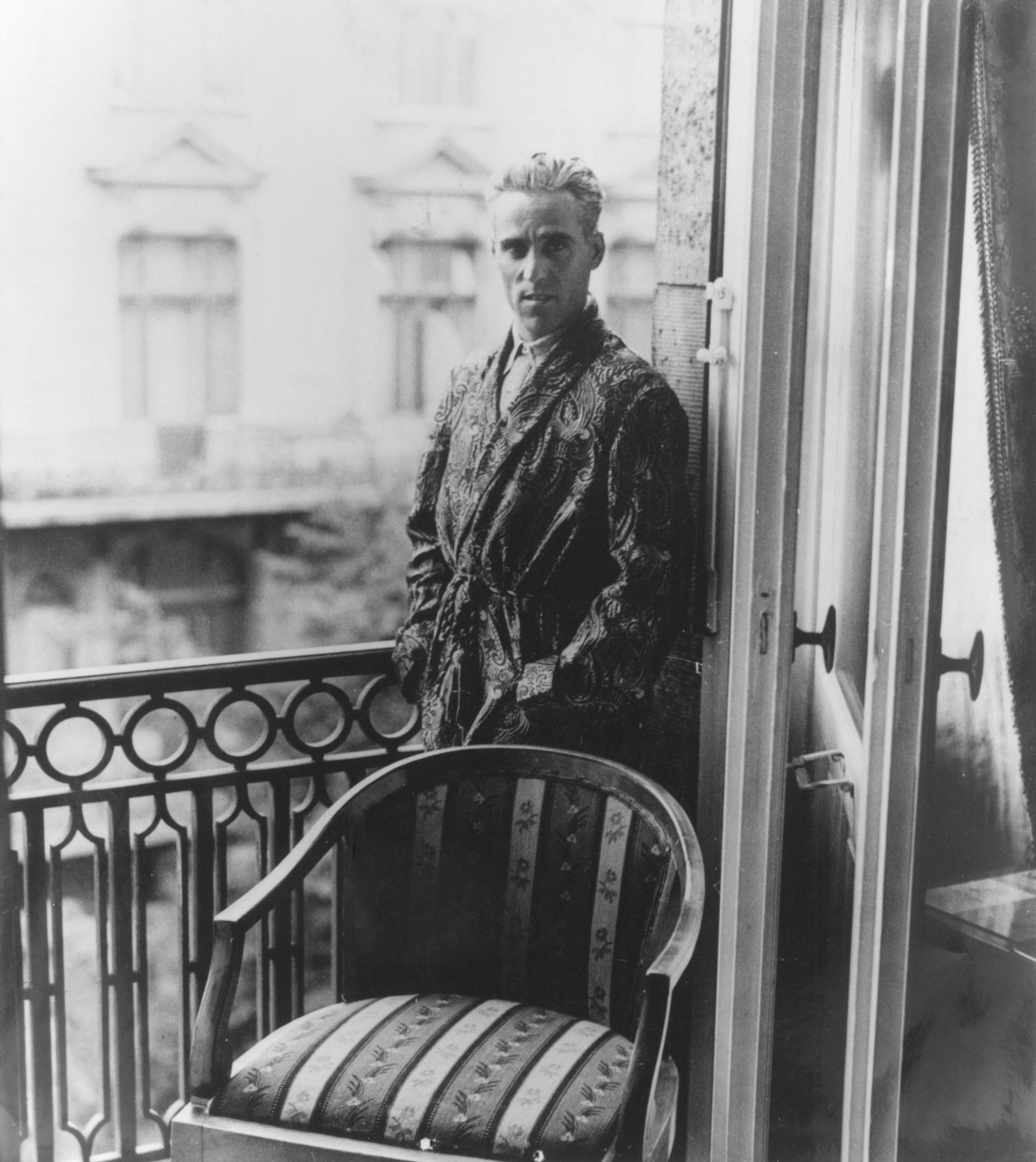

The visit took place on April 28, 1932, and should have taken three hours but it lasted seven. The Commander, resplendent in navy blue blazer and flannels, and Nuvolari, wearing a rather tight single-breasted suit and with his Brilliantined hair parted in the center, got on famously. After Gianferrari presented the poet with his new car on the Vittoriale’s magnificent terrazza overlooking Lake Garda, D’Annunzio and Nuvolari became so engrossed in conversation that they absent-mindedly wandered over to the new Alfa, sat down together on its running board and continued their deep discussion. Gianferrari, his test driver Pietro Bonini and the others just chatted among themselves.

Eventually, the two rejoined their friends: a few minutes later, everyone climbed aboard the Commander’s shiny new Alfa and left for a well-known watering hole called the Ristorante Cenacolo, where they enjoyed a splendid lunch.

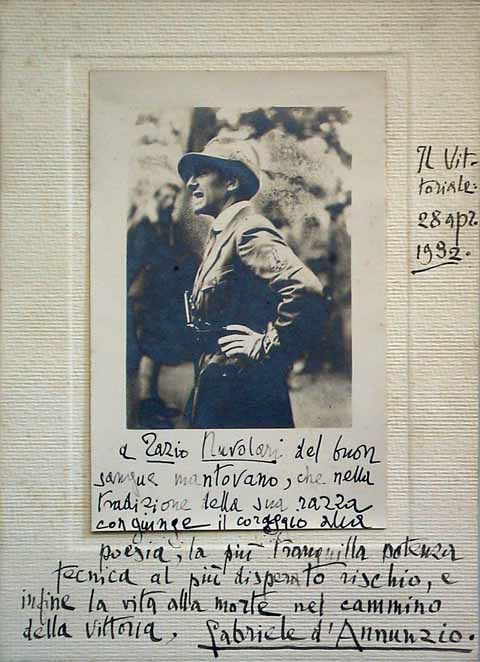

Replete with the glow and good will that fine dining and inspiring conversation can often encourage, D’Annunzio gave Nuvolari a photograph of himself in a somewhat Fascist pose, on which he wrote:

To Tazio Nuvolari, he of good Mantuan blood, who, in the tradition of his people, blends courage with poetry, quiet self-assurance and technical knowledge with the most desperate daring; and, finally, life with death on the path to victory.

Gabriele D’Annunzio

Back at the Vittoriale, the happy party relaxed for a while in the manor house’s sitting room – also known as “the room of pure dreams”, as it was the writer’s place of meditation – and there D’Annunzio tried to get Nuvolari to promise that he would win the upcoming Targa Florio.

The wily driver simply said, “When I race, I race to win. I swear it. You will see how fast I drive.”

As the visit was drawing to a close, the Commander took Nuvolari to one side and presented him with a gold tortoise, believed to have come from the 1928 batch, with his famous aside: “For the fastest man in the world, the slowest animal.” He told the diminutive Tazio the good luck charm would accompany him on his quest “for higher and beyond.”

Never one to miss a trick, after the visit Gianferrari had the Alfa Romeo PR department put out this press release:

Commander Gabriele D’Annunzio hosted at the Vittoriale Tazio Nuvolari, the driver, who was accompanied by Prospero Gianferrari, chief executive of Alfa Romeo. D’Annunzio expressed great satisfaction for the sporting successes achieved by Italian motor racing and, in particular, that which has been achieved by the Alfa Romeo workforce.

The Commander congratulated Tazio Nuvolari.

Ten days later, Nuvolari won the 1932 Targa Florio in his Alfa Monza, a victory that gave him particular satisfaction because it meant he had also kept his “promise” to his influential new friend.

[button link=”https://dev.sportscardigest.com//subscription-account/subscription-levels/” color=”blue”]Like this story? Click here to subscribe and have access to over 7,000 more, just like![/button]

D’Annunzio immediately wired Sicily:

You remember that, when we said our goodbyes, I was only smiling with one side of my face, ordering you to win in Sicily. You did not forget our agreement. When we left each other, we were both certain of your victory, thus our parting was the best I can remember among comrades. Your obedience makes you a legionary twice over. I am with you and your people in the land that the great emperor called the most beautiful. A warm embrace.

Gabriele D’Annunzio.

Nuvolari liked the irony of being the fastest man on four wheels whose mascot was a cumbersome tortoise: so he had another, larger gold tortoise made and engraved with the intersected TN logo he designed himself.

After what can only be described as a miraculous career, a great deal of it accompanied by his little gold talisman, Tazio Nuvolari died early on August 11, 1953, his lungs destroyed by incessant exposure to acrid engine fumes, fuel and cigarette smoke: but his mascot lived on.

From 1954 to 1957, a small gold tortoise was given to the quickest driver through the Cremona-Mantua-Brescia stage of the Mille Miglia and it is one of the trophies Stirling Moss, the fastest winner of that historic race, treasures most of all.

Each year, the Ferrari Club of Mantua still presents a little gold tortoise to an ex-Scuderia Ferrari driver of distinction. The first was awarded posthumously to Gilles Villeneuve and was presented to his widow, Joanne, in Mantua on 23 April 1983. Others have gone to Juan Manuel Fangio, Clay Regazzoni and Michele Alboreto.

Definitely one of your best stories. Thank you.

drr