Writing about vintage automobiles is great. There are rare cars to cover (“The Only One” Vintage Roadcar, December 2013), cars once owned by royalty (“Fit for a Prince!” Vintage Roadcar, June 2015), and dream cars (“Butterfly or Bee?” Vintage Roadcar, January 2107). Once in a while, though, there’s a car that just takes your breath away as soon as you see it. So it was when I walked into the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum (www.tbauto.org) and saw their Panhard Dynamic in person for the first time. It wasn’t the size of the car—it is large—nor was it the color—it’s silver, a fairly neutral color. It is just so Art Deco! Its streamlined shape took my breath away. Then, during a closer look, the details that the designers included caused my jaw to drop. The Panhard Dynamic is an incredibly beautiful automobile on the outside and very innovative underneath. I knew I would eventually have to profile that car.

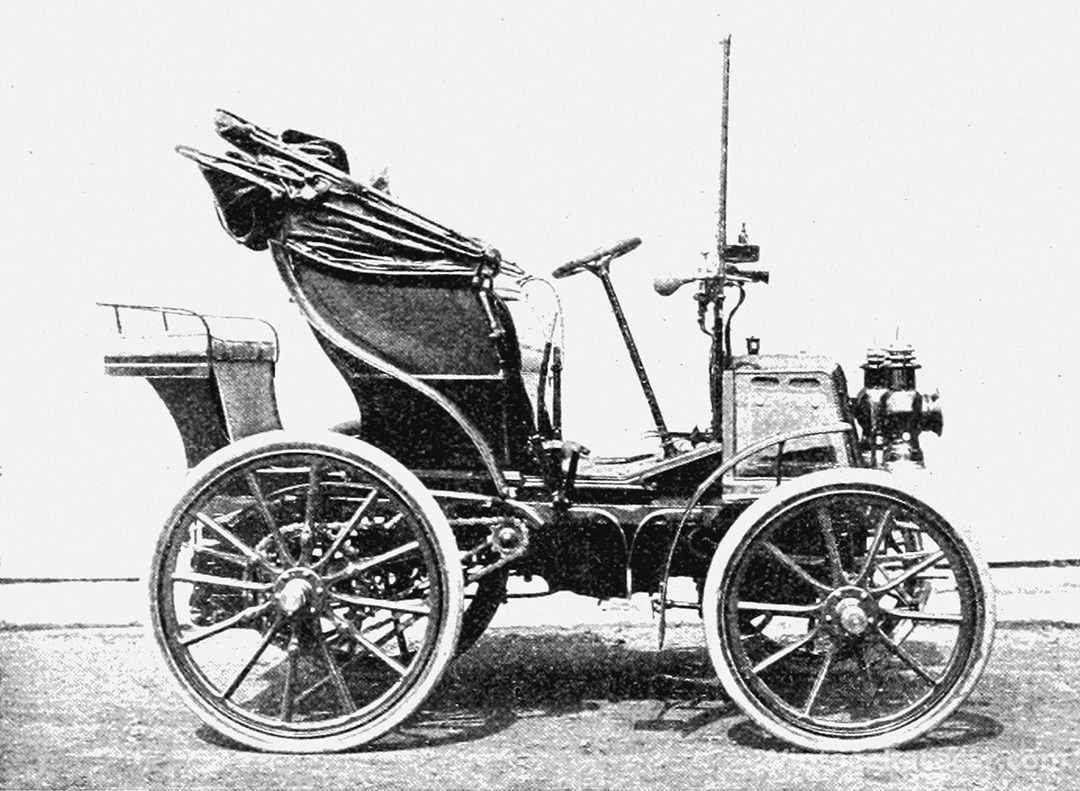

Panhard et Levassor is the oldest marque in the world with continuous production. Yes, Benz and Daimler had cars before Panhard, but they were one-off automobiles and not a part of sustained production. In 1891, Panhard et Levassor built four nearly identical automobiles then followed with a series of cars in increasing production numbers until the demise of the company’s auto production in July 1967.

The company has gone through several transitions, from being a maker of woodworking machinery to building some incredible cars, to being a manufacturer of military vehicles as a subsidiary of Auverland. It has passed through the hands of Citroën and PSA (the company name after the merger of Citroën and Peugeot). Throughout its history, however, it has simply been known as Panhard, even though it was Émile Lavassor, and not René Panhard, who was the automobile enthusiast.

There was also a significant loss to the company. Lavassor was injured in the Paris to Marseilles race in 1896. Rather than convalesce, he continued working and ultimately died on April 14, 1897. Eleven years later, on July 16, 1908, René Panhard died, and the company entered a new era.

After the deaths of Lavassor and Panhard, Panhard’s son Hippolyte and nephew Paul took over the company. Paul became the president of the company in 1916 and served until Citroën took over in the 1960s. While Hippolyte remained involved with the company until 1941, it appears that Paul Panhard had more to do with the direction of the company. One significant change resulted from being introduced to the Knight sleeve-valve engine in 1910. The engine was powerful, smooth and silent, and the company leaders were impressed enough to acquire a license to build them from Daimler. Sleeve-valve engines use two separately-moving concentric sleeves with ports near the top. They were moved up and down by small cranks driven by gears from the crankshaft. Gasses flowed when ports of both sleeves lined up with the intake or exhaust passages in the side of the block. While the engine had a near perfect combustion chamber shape, it would ultimately be shown that sleeve-valve engines had less volumetric efficiency than overhead valve engines. Sleeve-valve engines also had problems with cooling and lubrication. Cooling was a problem because the water passages could not surround the combustion chambers. Lubrication issues resulted in the use of a lot of oil, which meant that Panhards were often followed by a thin cloud of oil smoke. Still, the decision was made to use the engines because of their smoothness and quietness.

Panhard Dynamic

The arrival of a new technical director named Pasquelin, in the 1930s, moved the company closer to the goal of producing cars that emphasized quality, power and comfort. Together with designer Louis Bionier, Pasquelin and Bionier started designing cars, which became the ultimate Panhards. The cars they produced met all the quality and comfort requirements, and became more and more beautifully streamlined. The X74 showed some of the Deco details that began to appear on the Panhards designed by Pasquelin and Bionier. The X74 had several Deco details, including the door handle, side light and hood ornament—the design theme similar for each. The ultimate, however, was the Dynamic.

The Dynamic was the most significant achievement of the Pasquelin-Bionier collaboration. Designed in 1936, with 2,582 cars produced from 1936 to 1939, the Dynamic was, according to Jan P. Norbye, “…one of the most outstanding combinations of engineering and styling that came out of the Thirties” (Automobile Quarterly Volume VI, Number 2). This car was as much dream car as production car. One of the most unusual features was its central driving position, allowing three people to sit across the front seat, as well as three in the rear. It featured unibody construction, had a low center of gravity and very low drag. It took what was started with the styling of the X74 to its logical conclusion: every detail carried the Deco theme—hood ornament, headlight, side light, door handle, oil filler cap and spare tire hold down. The car even had a stylized turn and stop signal on its right rear fender that proudly proclaimed that it was French.

The thought and innovation that went into this car was exceptional for the time and went far beyond its artistic elements. The Dynamic was very progressive. In addition to its sleeve-valve engine, unibody construction and three-across seating, the car had a torsion bar suspension front and rear, independent front suspension with two shocks per wheel, dual circuit drum brakes with a single brake shoe that operated over 340 degrees, four-speed transmission with freewheeling and worm-drive rear axle. Carburetors were a Panhard design that included a cavity that holds a small amount of gasoline to make starting easier. Once started, the fuel pump moves fuel to a tank where it is gravity fed to the carburetors. The muffler was located under the radiator, so that the hot radiator dried the muffler to keep it from corroding. Upper and lower control arms were hooked to the engine, so when the body is removed, the engine, transmission, and suspension are all left together. Bionier solved one potential problem for a driver located between two passengers—he invented a two-piece windshield pillar with curved glass to give the Dynamic driver an incredible, unobstructed view of the road.

Dynamics were big cars and owning one was prestigious. They were very popular with the military and the clergy. The Bishop of Notre Dame had one. In 1936, the entire country was on strike, but the Prime Minister got the strike stopped long enough for a Dynamic to be built for him.

Serial Number: 222102

The collection at the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum belongs to Alain Cerf, the owner of Polypack, a company that makes packaging machines. His interest is in “automobile engineering mainly in the late ’20s and ’30s when engineers came [up] with new ideas.” The cars in the museum emphasize design innovation and technology. A Panhard Dynamic would fit in the collection nicely, but they are very rare in the U.S. Still, Cerf was able to find one. It was located in Hyannis, Massachusetts, but was being sold through a dealer in California. It was listed for sale “as is,” always a daunting phrase when looking for a classic car. The car did run, but it needed brake work—simple enough for the restoration staff at the museum—so a deal was made, and Cerf bought the 1938 Panhard Dynamic in January 2000. It was a Berline, the model with the longest wheelbase, and it had the 2861-cc, six-cylinder engine that produced 75 hp, giving a top speed of 135 kph, or about 84 mph. With a bit of work, the Panhard joined the collection and is now prominently displayed.

Driving Impressions

Open the door, move inside, and close the door—the car is so well built that you can close the door with only slight pressure from one finger! Once inside, the first impression is that this thing is big! In fact, it is approximately five feet wide, which makes it a bit awkward to slide across the bench seat to the middle of the car, but once there, it is very comfortable. Cerf says, “It is a French car; the steering wheel is in the middle so you can have a girl on each side.” And there is room enough for two adults to sit comfortably beside the driver. Visibility is incredible—you can see from side to side without any obstructions. The dash stretches to your left and right, with speedometer, odometer and ammeter on your right and water temperature and fuel gauges, clock, directional blinkers, and a star that when lit indicates that the engine is running—and that star really is needed, since the engine is so smooth and quiet it is hard to hear or feel it running.

It helps to have a “translator” with you when you drive a Dynamic for the first time. There are a plethora of knobs and controls, and none of them are marked. Some of them have more than one function. The glove box knob can be pulled to open the glove box or turned to open the windshield from its bottom for additional air circulation. “If you own a Panhard, you know,” says Cerf.

The start knob to the left of the steering wheel is the on/off switch. It also opens the fuel reservoir so there will be enough fuel to the carburetor to start the car. Once on, just step on the starter button on the floor, and the car starts, or so the lighted star on the dash tells you. This car is really, really quiet. Ready to roll, the “translator” describes the shifter. It’s to the left of the steering wheel and is a “rifle bolt” type—push in for first, second is out then twist to the right and back in again, third is straight out from second, and fourth is in a little then a twist to the left and back out. I was a bit nervous about getting the car moving, since I was told to “slam” the shifter into first, but I did. It takes quite a bit of gas and clutch manipulation to get this big car moving, but once it’s going it is as smooth as it is quiet. The clutch is stiff and engages right at the top, so it takes a bit of feathering. The free wheel allows you to avoid the stiff clutch. It has a vacuum servo, so when you lift off the throttle, it pulls in the clutch for you. You shift, and when you press on the throttle, it releases the clutch. Very clever! I had not driven a car using the free wheel before, so it was nice not to have to use this particular clutch.

Steering is pretty stiff, and the turning circle is wide. The car is not meant to be a sports car, so the handling isn’t spectacular. But for what it was intended to be—a luxury car—it does everything right. It is a very comfortable automobile, and I could see why generals and bishops liked it. Because of the sleeve-valve engine, you are followed wherever you go by a trail of oil smoke. As Cerf relates, “You can adjust the oil for the smoke, but that is dangerous, because if there’s no smoke, you are in trouble.” When you’re inside a car this beautiful, comfortable and quiet, you really don’t care about a trail of smoke. For a lover of Art Deco such as myself, driving this car was a check on my bucket list.

The Demise of P&L

The Dynamic was one of the most significant production cars of the 1930s, both because of its engineering and its styling, as Norbye noted. In the Depression, unfortunately, large, luxurious cars were no longer in demand. Production of these ultimate Panhards ended in August 1939, as France mobilized for war. During World War II, Panhard was forced to build trucks and tank treads for the German military, although they also developed a gas generator that burned wood or charcoal to power civilian vehicles.

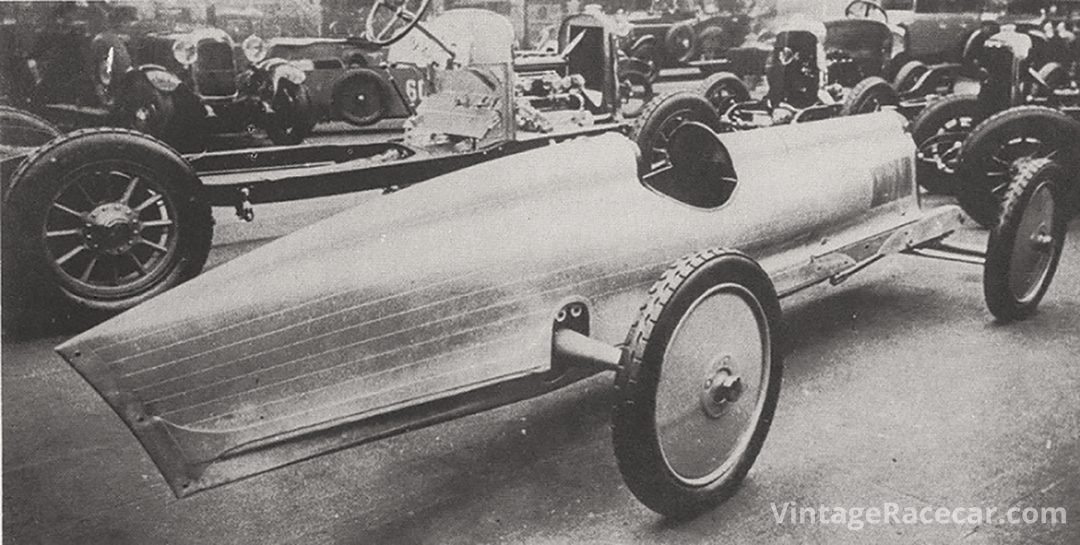

After the war, Paul Panhard wanted to resume building big cars, but his son Jean convinced him to concentrate on smaller cars. Somehow, though, Panhard et Lavassor was left out of the post-war allocation of raw materials—the Pons Plan—so production could not proceed. Jean Panhard provided the solution when he learned that the Aluminium François prototype designed by Jean-Albert Grégoire was available and bought the design. With the support of Aluminium François, Panhard was back in business. The resulting car, the Dyna Panhard, was first shown at the Paris Salon in October 1946. It was a four-door sedan with a 610-cc, air-cooled, flat-twin producing 24-hp at 4000 rpm. The new Panhards were very successful, and the engines were popular with small manufacturers of sports cars such as Deutsch-Bonnet and Arista.

In 1955, Citroën bought 45 percent of Panhard shares and imposed design changes. Still, Panhard remained successful until, in 1965, Citroën took complete control and created the Société de Construction Méchanique Panhard et Lavassor to produce only military vehicles. The last Panhard automobile was finished on July 20, 1967. Sadly, when small, innovative companies are swallowed by the bigger fish, they disappear.

Norbye possibly had the best description of the company: “In the glorious past of Panhard et Lavassor there are elements of a Shakespearian play or Tolstoy novel: dedication and energy, devotion to duty, respect for tradition and enchantment with the radical, endurance and singleness of purpose, intrigue and diplomacy, friendship and trust, love and romance.” Sadly, none of that was enough to ensure the company’s future, but we can thank organizations like the Tampa Bay Automobile Museum and Lane Motor Museum (www.lanemotormuseum.org) for preserving examples of Panhard cars for us to see and enjoy.

Body/Chassis: Steel unit body

Drive: Front engine, rear-wheel drive

Engine: Sleeve-valve, inline 6

Displacement: 2861 cc

Power: 75 hp

Transmission: Four-speed with free wheel

Rear Axle: Worm drive

Front Suspension: Independent with torque rods and two hydraulic shocks per side. Suspension part of the cast aluminum engine block

Brakes: One shoe drum with dual hydraulic circuit

Wheelbase: 2800 millimeters/110 inches

Length: 5150 millimeters/205 inches

Width: 1900 millimeters/75 inches