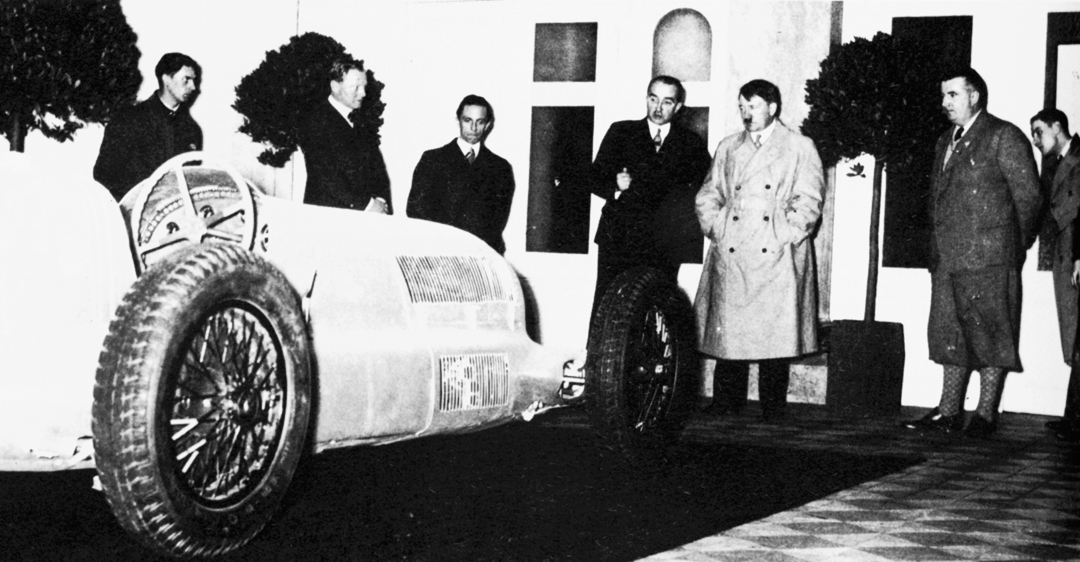

A shortish, miserable-looking man with a square moustache strutted into the room, his face non-committal, his uniform vaguely operatic. He had come to see what he had got for his money.

He stopped in front of the silver racing car and scowled. A man in a business suit described the car to the poker-faced despot, while his entourage stood a respectful distance away in their Sunday best. Adolf Hitler stared dolefully at the new Mercedes-Benz W 25 and wondered if it would do the trick.

The entire Grand Prix project came about after Hitler, who was then the freshly elected Chancellor of Germany, went to see the 1933 Avusrennen near Berlin. He was appalled to note that there were no German cars in the first three places, the winner being Italian Achille Varzi in a French Bugatti.

So the Führer let it be known that he wanted new energy pumped into German motorsport. And he wanted victory for the Fatherland. The propaganda value of German technology’s success in the world’s most exciting sport was not difficult to see. But the German car manufacturers groaned and resisted as much as they dared. The depression that had swept Hitler to power was hitting them just as hard as the rest of German industry, so they were reluctant to spend money on an expensive pastime like motor racing.

Photo: Audi

Noting the constructors’ reticence, Hitler seized upon another idea: he would offer them some money—half a million Reich marks, or about $700,000 in today’s terms. Not much when you consider a serious Grand Prix program in the early ’30s could cost between 5 and 10 times that amount, but enough to bait the hook and set a few gray cells working. As expected, Mercedes-Benz bit, but much to their consternation so did Auto Union, a newly formed alliance between Audi, Wanderer, Horch and DKW. At first, the Führer was sceptical, but eventually accepted the two bids for his money. The only trouble was that he did not double the sum on offer, as could have been expected now that there were two hats in the ring: he split it down the middle. The 500,000 Reich marks were shared out 50-50 and the revered, long established Mercedes-Benz did not like that one bit. About $350,000 apiece for a racing program that would cost much more was not exactly their idea of heaven, but they bit the bullet.

Next, Hitler appointed Major Adolf Hühnlein, a humorless career soldier, as boss of all German motorsport and gave him the impressive title of Korpsführer. He did not run the teams; they did that themselves. But he did run the infrastructure. You want to close the autobahn for a land speed record attempt? Talk to Hühnlein. You want to employ a foreign driver? Same thing, except that the last word on that one was always Hitler’s. The Korpsführer oversaw all races and record attempts that took place on German territory, reporting directly to Hitler after each event. His grovelling accounts, heavily laced with the Nazi vernacular, were a crawler’s work of art.

Ironically, the Führer never actually saw the Silberpfeile or Silver Arrows compete, but Grand Prix motor racing provided Goebbels with a heaven-sent opportunity to intensify his “Volksbrainwashing” both at home and abroad.

Part of Hühnlein’s job was to ensure the circuits, and any other venue at which the Silberpfeile were due to perform, were turned into vast Nazi stages, festooned with as many swastika flags and banners as each location could sensibly accommodate. And the cars certainly made their contribution to projecting an aura of steel-fisted might, with the gut-wrenching roar of their big engines and, later, the blood-curdling howl of the smaller units’ superchargers. They looked and sounded full of menace as they blasted their way around half the world’s circuits at speeds of more than 270 mph.

The Silberpfeile were designed by two distinctly different teams of engineers and the results of their efforts were just as diverse, with the Mercedes-Benz equip, headed by Dr. Hans Nibel, and the Auto Union group guided by Professor Ferdinand Porsche. To begin with, Stuttgart came up with the front-engined W 25, an 8-cylinder, 3,363-cc racer that put out 354 hp at 8,500 rpm and had a top speed of 174 mph. Zwickau, home of Auto Union, decided to take an extremely unconventional tack that would have a major impact on the future of Grand Prix motor racing, right through to the present day. Their long, slender car was powered by a 16-cylinder, 4,358-cc engine located behind the driver for better handling: the unit generated 295 hp at 4,500 rpm and it, too, accelerated to a top speed of 174 mph.

The cars were incredibly successful, but that had everything to do with the brilliance of their engineers, technicians and drivers who designed, built, maintained and raced them and nothing to do with Nazi chicanery. Between April 2, 1934 and September 3, 1939—the day the Second World War was declared, when Tazio Nuvolari brought this Golden Age to a close by winning the Grand Prix of Yugoslavia for Auto Union—the Silberpfeile won no fewer than 58 out of a possible 70 Grands Prix, won seven German Hillclimb Championships and established 60 land speed records, 20 of them world class. They were spectacular achievements blatantly manipulated by Goebbels and his Nazi propaganda machine.

There is no denying that the Grand Prix of Germany, for instance, was a major event at the Nürburgring. More than 500,000 people would pack the 14-mile long circuit on race day, all eating sausage, guzzling beer and clicking stopwatches as their favorite drivers howled past for another 14-mile lap.

Carnival time in the nearby village of Adenau began about a week before that: the little fairytale houses suddenly broke out into a rash of swastika flags large and small and shops would do a roaring trade in all kinds of knick-knacks and memorabilia. The drivers were idolized like Hollywood stars. The visitors who flooded Adenau kept close tabs on their every move, partly just to see them but mainly to pounce with pencil and paper any time an autograph opportunity cropped up.

The build-up reached its peak in the 24 hours before race day, with spectators pouring into the area aboard every conceivable form of transport, from bikes to huge trucks and buses, all dutifully decorated with Nazi flags, their occupants bellowing an extensive repertoire of traditional and Nazi songs. It took more than 120 parking lots to accommodate all their vehicles.

On race day, Korpsführer Hühnlein strutted around the Grand Prix circuit in his bemedalled Nazi uniform, dispensing characteristically sour looks and rebukes to all and sundry: with his direct line to Adolf Hitler, he felt very much the man in charge. Before each race—the German Grand Prix, the Eifel GP and the Avusrennen—Hühnlein gave a brain-numbing propaganda speech to the assembled half a million, who listened in hushed reverence. Riveting stuff like “The glory of the Third Reich…”, “Invincible German technology…”, “German superiority…”, “For the Fatherland…” and, of course, an abundance of “Heil Hitlers” were all given repeated exposure.

Hühnlein headed up the NSKK, by the way, a kind of drivers’ regiment in which each held rank in line with his prowess. For example, Bernd Rosemeyer was promoted to Obersturmfuhrer (first lieutenant) when he won the 1937 Eifel Grand Prix in dense fog at the Nürburgring. He was given a further leg up to Hauptsturmfuhrer (captain) that same year, after his victory in the richly rewarding Vanderbilt Cup. But by all accounts, none of the Mercedes or Auto Union drivers of the day became involved in the politics. Even as members of the NSKK they were not expected to do much, except wear a badge on their driving suits every now and then and say a few politically correct words to the over-inflated Hühnlein when the occasion called for it.

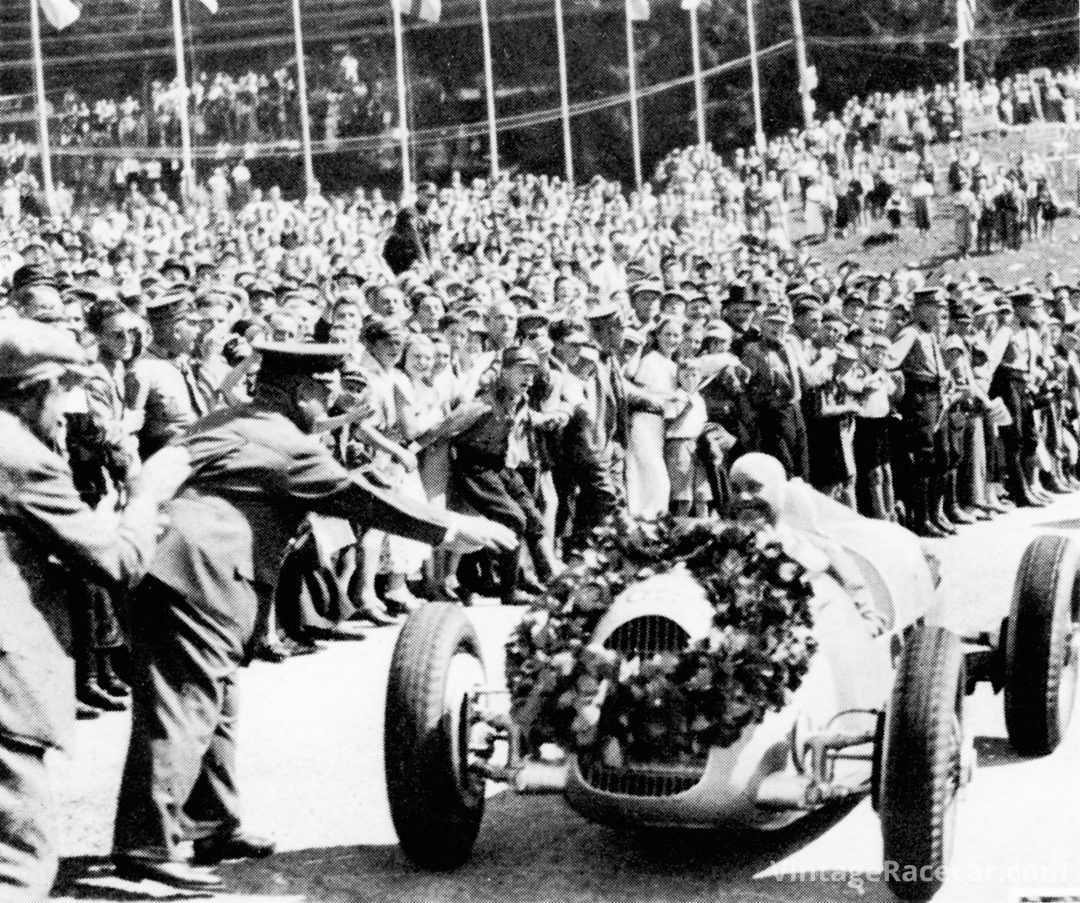

Literally thousands of soldiers lined the circuits before the assembled hoards and yet more gave their mechanical display of goose-stepping in front of the stands as a band serenaded spectators with tedious military marches and, of course, “Deutschland Uber Alles” when the moment demanded. Then, with much throttle blipping, the cars made their way to the pits and that sent the crowds into delirium as the Silberpfeile lined up herringbone fashion before their adoring fans, the German cars first, of course. Next, a regiment of helmeted storm troopers streamed onto the track and marched to the pits, an enormous-sized Nazi flag fluttering at the head of the column, to line up before an assortment of gauleiters and other party faithfuls attending the race. Cue a fleet of shiny Mercedes-Benz cars in which top Nazis in their macabre black SS and other uniforms sat ramrod straight, accompanied by Hühnlein. More “Deutschland Uber Alles” blasted out by the band as an even bigger swastika flag broke on its mile-high pole and was slowly hoisted aloft to the accompaniment of half a million Nazi salutes from those attending. After more “Heil Hitlers” and heel clicking from VIP to VIP, it would be time for another of the Korpsführer’s little speeches, which he would spit vehemently into the microphone. The troopers would then take their leave, the drivers, by this time drawn up on the grid, would increase their engine warming from throttle blipping to a mighty crescendo and, by strange comparison, a reverential hush would descend over the amassed spectators. A cannon would be fired and the cars would race away to their destiny.

The car manufacturers’ workers and ordinary members of the public were not forgotten in times of victory, as they were as much a target of Nazi propaganda as the people of foreign countries, all wrapped neatly in Grand Prix victory after Grand Prix victory. Many is the time the factory Mercedes and Auto Union cars were paraded through the streets of Stuttgart and Zwickau after a win, sometimes piloted at a snail’s pace by their accelerator-blipping star drivers and shepherded by columns of police outriders, sometimes on the backs of trucks looking like stranded whales. Multitudes of swastika flags and banners would be draped over an open air speaker’s platform and flail energetically from flagpoles, fences and windows as the victorious driver would tell his starry-eyed audience how he had won. A band would strike up with “Deutschland Uber Alles” again and every man, woman and child would shoot their right arms up towards the heavens in a Nazi salute, the proceedings all laced with large helpings of storm troopers and police.

But Germany’s share of the Golden Age was not all sweetness and light. There were a number of flies in the Nazis’ ointment, not the least of which was Tazio Nuvolari’s fabulous victory in the 1935 Grand Prix of Germany driving an obsolete Alfa Romeo P3. The class was provided by the mercurial little Italian’s outstanding driving ability, with which he gradually managed to get his old red car past all the state-of-the-art Silberpfeile, until there was nothing between him and the win. So confident were the race officials of a great German victory, that they took ages to find a recording of the Italian national anthem, resulting in a lot of foot shuffling and embarrassment all a round. Korpsführer Hühnlein’s speech praising the sons of the Fatherland for their efforts remained in his pocket and he was forced to improvize another along the lines of “our glorious Italian allies.”

Another ointment spoiler was Englishman Dick Seaman, who won the 1938 Grand Prix of Germany in one of the much-vaunted Mercedes-Benz. Huhnlein, of course, nearly had apoplexy. Garlanded with the victor’s laurels and adorned with the obligatory silk ribbon with swastika, the tall, suave Seaman stood next to the Korpsführer trying to come to terms with what he had achieved: he had beaten the Germans at their own game in one of their cars on their very own Nürburgring. The incredibly embarrassed Huhnlein mentioned the Englishman over the circuit’s loudspeaker system as little as possible as he played up the brilliance of Reich technology and the winning Mercedes-Benz. His report to Hitler immediately after the race must have made interesting reading!

By this time, Seaman was becoming more and more disenchanted with Germany and its increasingly belligerent stance. He felt he could not justify driving for the Germans much longer, so he had a face-to-face with Mercedes team boss Alfred Neubauer on the subject, and that developed into a full-blown argument. As tempers frayed, Seaman let rip and called the Fuhrer a liar. After a stunned silence, fearful that such “blasphemy” might be overheard by some Gestapo mole, Neubauer told young Richard to shut up, to which the Englishman said he was used to being able to express himself freely. Neubauer really had no answer to that, as the Third Reich had dispensed with such niceties as freedom of speech a long time before the clash.

How did a British driver ever get to join a German team at such a time? Well, it all started with a telegram from Stuttgart asking Seaman, who had just won Donington with Hans Ruesch in the Swiss driver’s Alfa Romeo Tipo C 8C-35, if he would like to take part in a Mercedes-Benz driver trial at the end of 1936 at the Nürburgring. The biggest problem the Briton had to wrestle with was, of course, the political one: it was pretty obvious that the Nazis were limbering up for war and would soon become his homeland’s enemies. Should he drive for a potential enemy? He sought advice from friends and colleagues, most of whom told him that, if a drive were offered, he would be crazy to refuse it: Mercedes was Mercedes, when all was said and done. The test session went well and Seaman signed a letter of intent, which eventually turned into a proper contract after Hitler had, surprisingly, approved the Englishman’s recruitment.

Money, however, was a different thing entirely. The Nazi regime strictly forbade anyone from exporting Reich marks. Seaman’s Mercedes-Benz retainer was the equivalent of $20,000 in today’s dollars, plus prize money—against Caracciola’s $250,000—but neither could get their earnings out of the Fatherland. Not that Dick Seaman needed the cash back home: his late stepfather and his mother had both been independently wealthy before they met and married.

Three times European Champion Rudolf Caracciola suffered from the same restrictions. He had lived in Lugano since 1929, something that did not go down at all well with the Nazi regime. When he married his live-in girlfriend—Louis Chiron’s ex, Baby Hoffman—in the Swiss lakeside town in 1937, he tried to withdraw money from his German account with which to buy his bride an expensive wedding present. But the Nazis blocked the transaction. They did not look kindly on their greatest motor racing hero ducking his military obligations, deserting his homeland and living in another country. In 1942, the party found out that Caracciola was still on the Mercedes-Benz payroll, so they soon put a stop to that, too: as the war ground on, the couple found it hard to make ends meet and were all but penniless by the end of hostilities.

Other drivers had their problems with Hitler’s murderous regime as well, especially the urbane Hans Stuck. Placards were waived at him as he competed in the 1935 Feldberg hillclimb—which he won—accusing him of being married to a “Jewess.” Auto Union’s Zwickau headquarters were even daubed with graffiti making similar anonymous charges. The fact of the matter is that his wife’s grandfather was Jewish, not her. Under pressure, poor Stuck even contemplated retirement and departure for neutral Switzerland to escape the cowardly persecution.

Both the Stucks were famous in Germany, Paula as one of the nation’s top-ranking tennis players and Hans, of course, as a motor racing star. But that did not stop them being hounded by the feared Gestapo. One night, two leather-coated men even raided their Monte Carlo hotel room and started firing questions at them, wanting to know where they obtained the money with which they had been gambling in the principality’s casino. Stuck was enraged, refused to answer them that evening and said he would do so the following morning: the investigators were later banished by the Monaco authorities.

After a derogatory story about Paula Stuck being a Jew appeared in one magazine, Hans felt obliged to send a letter to the editor in which he said his wife was not Jewish but, as the Nazis so humiliatingly categorized her, she was registered as a person of mixed blood. He also confirmed that, contrary to gossip doing the rounds at the time, he and his wife would not be leaving Germany and he would still drive for Auto Union—or so he thought.

At the end of 1937, Auto Union decided not to renew Stuck’s contract for the following year and cited some incompatibility with his teammates and diminished results as the reasons—others thought they were rattled by the accusations against his wife. So the SS became involved—on the driver’s side. There were rumblings from Berlin at Stuck’s summary dismissal, but Zwickau could not understand why the SS were so concerned: so the company decided to make some discreet enquiries. The result made them back off fast, but not enough for the SS’s liking. It turned out that, some time earlier, Hans Stuck had written a letter of complaint to Reichsfuhrer Heinrich Himmler, who was the head of the feared SS, Gestapo and the Nazi death camps, after the appearance of those vicious 1935 placards and the graffiti. His note eventually reached the Führer himself and Hitler ordered that the issue of Paula Stuck’s Jewish heritage be dropped and that Stuck be allowed to continue racing unhindered. Himmler informed Auto Union that he would not be at all pleased if a driver of Stuck’s stature was fired by the team.

This really alarmed Auto Union, but it did not repent completely. Instead, it announced that Stuck’s contract would be renewed, but he would become a private entrant and drive their previous year’s car, competing mainly in mountain and hillclimbs. Himmler was furious at this half-measure and spat new instructions at one of his minions. The Reichsfuhrer’s aid told Auto Union that Himmler was “concerned” that Stuck was still being mistreated and wished to make it clear to the board of directors that he would be “displeased” if Stuck were not reinstated as a full member of the team. People who “displeased” the Reichsfuhrer tended to disappear into an SS dungeon, never to be seen again. Now, clearly understanding the risks they were running, the Auto Union board had no alternative but to bring Stuck back as a full member of the team—and he duly won the 1938 European Hillclimb Championship for them.

Unknown to the Führer, Hitler’s lackeys severed Stuck’s lines of direct communication with their boss, who received no word of the driver for some time after the Auto Union contract incident. That worried Stuck, until the 1939 Berlin Motor Show. Hitler made his customary visit to the Auto Union stand, noticed Hans Stuck and shook him warmly by the hand.

Anti-Semitism tainted the Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union teams’ Atlantic crossing on the Bremen as they sailed off to compete in the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup on New York’s Long Island, “chaperoned” by two dyed-in-the-wool Nazis: one was a particular friend of the Führer’s and never tired of reminding everyone of the fact. The teams were invited to join the captain’s table for dinner on the way out, but when the two Nazis found the next table was occupied by a Jewish family, they remonstrated with the captain. Hitler’s friend told the commandant he should make it his business to see Jews were no longer allowed on board German ships. But the captain was not having any of that and argued with the Nazis, who reported him when the Bremen returned to the Fatherland. Young Ferry Porsche was also travelling with the teams and danced with the offending family’s pretty daughter, after which one of the “chaperones” told him off for dancing with a Jew.

But their journey proved worthwhile and brought yet more glory to the Nazi cause: the race was won by Bernd Rosemeyer for Auto Union with Dick Seaman finishing 2nd in a Mercedes.

The Silver Arrows would go on to win another 18 Grands Prix out of a possible 19—only Rene Dreyfus beat them in a Delahaye to win the 1938 Grand Prix of Pau—before Tazio Nuvolari brought a quite remarkable motor racing epoch to a close by winning the Grand Prix of Yugoslavia the very day the Second World War was declared.

The Mercedes-Benz and Auto Unions of 1934–39 had the misfortune of being born into an era rife with pervasive racial hatred and jingoism, but even so their achievements still shine through such abominations like a beacon. The Golden Age would have been far less golden without the Silver Arrows.